Australian Industries Environmental Performance

advertisement

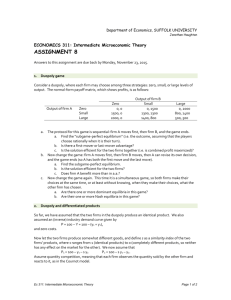

Australian industries environmental performance: Depresses accounting numbers but enhances market value Noor Muhammad1, Frank Scrimgeour2, Krishna Reddy3, Sazali Abidin3 Abstract In this study, we investigate the association between environmental performance and financial performance of public-listed companies in Australian Stock Exchange which submitted environmental report to the National Pollutant Inventory (NPI). After controlling for unobserved firm effects, time variant affects and applying new empirical proxy for environmental performance, this study finds that there is a strong association between environmental performance and financial performance. From market based financial performance perspective, overall results show that there is a positive significant effect of environmental performance. However, from accounting based financial performance view, overall results show negative association. Only one model finds positive association from both accounting and market based financial performance. The results from this study suggest that managers should have least or no concern for the depressed accounting performance as firm environmental performance overall improves investors’ perception and enhances corporate market value. 1 Doctoral Candidate, Department of Finance, University of Waikato Management School Professor, University of Waikato Management School 3 Senior Lecturer, Department of Finance, University of Waikato Management School 2 1 Australian industries environmental performance: Depresses accounting numbers but enhances market value 1 Introduction The quest for financial stability and sustainable finance is an on-going process. Managers scramble to bring financial stability to their companies. They must do so by having regard to the common and precious commodity of environment. Managers are normally trying to enhance company performance in terms of shareholders value. Therefore, it is argued that if shareholders regard manager’s action in favour of environment, then it must be reflected in company’s market value of equity. Therefore, in absence of regulatory compliance, corporate environmental performance ultimately means shareholders response towards environment. Extant literature over three decades has inconclusive results about this issue. According to the Horváthová (2010) review of literature, 55% of studies find a positive, 30% find a negative and 15% find no association between improved environmental practices and financial performance. Therefore, the case for sustainable finance is inconclusive. To identify whether or not shareholder regard environmental performance in terms of market value of firm, we need to solve the puzzle on what actions of firm should be considered as environmental performance. Unlike financial performance, environmental performance of firm is not straight forward. It is more abstract phenomenon and it is hard to translate it in quantitative measures. The risk of mis-measurement will clearly mis-represent environmental performance and ultimately lead to inaccurate results and analysis. Historically, researchers have used range of environmental performance proxies. It includes from qualitative measures to quantitative measures like emission of pollutants. It is evident from literature that researchers have either used some particular pollutants or gross amount of pollutants with different level of toxicity to investigate environmental and financial performance nexus. This 2 lack of normalization in environmental performance measure is because of data availability and limited knowledge about toxicity of different pollutants. We adopted an innovative measure of environmental performance for the first time presented by Muhammad and Scrimgeour (2012) to empirically investigate Australian listed companies from 2005-2010. The motivation of this research is to investigate the environmental performance and financial performance association in the Australian context. Environmental consciousness among Australian firms is still an empirical mystery that needs to be explored. It is pertinent to note that the literature is dominated by Anglo-American empirical evidences (Horváthová, 2010). After adopting international accounting standards for reporting purposes from 1 January 2005, Australian companies data is now more comparable to corporation working in international accounting standards regimes (Australian Accounting Standard Board, 2004). Environmental performance measure data is taken from National Pollutant Inventory, Australia. A similar kind of database (European Pollutant Release and Transfer) is also adopted by many European countries. Therefore, the results from this study are comparable with other similar American and European studies. In next section, we cover earlier work related to our topic followed by data and its sources. We proposed econometric model in section 4. Results and discussion are presented in section 5. Last section concludes the study. 2 Literature Review The review of literature on nexus of environmental performance and financial performance show inconclusive results (Horváthová, 2010). Waddock and Graves (1997) argued that shareholders do not penalise manager for allocating some of resources towards corporate social performance including environmental performance. Improved relations with key stakeholder groups will indeed encounter fewer difficulties and attract new equity 3 investments to the firm and maintain benefits to firm’s value. Echoing this, Horváthová (2012) concludes that investors value environmental performance. Although environmental performance has negative impact in short run but it has positive impact in long run. Contrarily, Cordeiro and Sarkis (1997) have showed that there is no proof that firms sacrifice profits for social interest. Firms voluntarily adopt environmental protection measures and assume green responsibilities only when it maximizes their market value, as a firm’s primary objective is considered to maximize the stockholders wealth. In general, corporate environmental performance literature can be divided in two broader strands: 1) the first group of studies can be differentiated on the basis of environmental performance measures and 2) the second group of studies can be identified on the basis of econometric methodology. Each of the above group is further divided into three subgroups. Delmas and Blass (2010) have divided environmental performance indicators into 3 main categories: (1) Environmental impact: emissions, usage of energy, toxicity/spills, plant accidents and aftermaths of these accidents e.g. Bhopal Carbide factory incident in India or more recently British Petroleum (BP) oil spills in the Gulf of Mexico (2) Regulatory compliance: mandatory installation of treatment and recycling plant, lawsuits concerning improper disposal of hazardous waste and fines for its clean up (Cordeiro & Sarkis, 1997; Khanna & Damon, 1999; Klassen & McLaughlin, 1996). (3) Organization process: improvement in environmental management systems, organisation processes and capital expenditures in pollution control technology (Gilley, Worrell, Iii, & Jelly, 2000; Klassen & McLaughlin, 1996; Montabon, Sroufe, & Narasimhan, 2007; Watson, Klingenberg, Polito, & Geurts, 2004). Different stakeholders use a mix of the above categories to define environmental performance. Similarly, Ambec and Lanoie (2008) have categorized research methodologies into (1) 4 portfolio analysis, (2) event studies and (3) regression studies. In portfolio studies, different equity portfolios’ financial performances are compared with environmental performance. For example Cohen, Fenn, and Konar (1997) divided companies into high polluting firms portfolio and low polluting firms portfolio. Event studies analysed the response of particular events like release of emission data, awards or lawsuits cases of particular stock and its financial performance. Whereas, in regression analysis, researchers compare the relationship between firms’ characteristics which include environmental performance and financial performance. Bragdon and Marlin (1972) study is considered as the pioneer in this area of research. They used pollution data from Council on Economic Priorities 4 (CEP) Environmental Performance Rating5 in the United States for environmental performance. Simple correlation coefficient showed positive impact of environmental performance on financial performance. Later on, Spicer (1978) used firms in paper & pulp industry to measure association between better environmental performance and financial performance. Although the sign for correlation coefficients were aligned in the hypothesised direction but only 3 out of 6 financial measures were significant. Studies in 1970’s faced criticism for using small sample size and measurement error. For example Chen and Metcalf (1980) used the same data set as Spicer (1978) and showed that the positive association disappear by introducing control variables. Despite of criticism, these studies still sparked the idea that better environmental performance and financial performance are complements. This idea is also acknowledged by Narver (1971) that reducing externalities particularly reducing pollution will reduce variability in earnings and hence increase firm’s value. 4 CEP is a non-profit organization formed in 1970 to promote socially responsible business policies and practices including environmental performance of firm in four sectors: electric utilities, steel, oil and paper and pulp (Abbott & Monsen, 1979) 5 Early US studies used this data exclusively for environmental performance measure (Al-Tuwaijri, Christensen, & Hughes, 2004) 5 Despite findings of positive impact of environmental performance over financial performance in early studies, researchers in 1980’s generally found negative relationship. For example, Mahapatra (1984) claim that pollution control expenditure either legally or voluntary is drain of resources and thus concluded that investors in general are not ethical investors. Similarly, Rockness, Schlachter, and Rockness (1986) examined environmental performance impact of chemical industry. They analysed hazardous waste disposal data from a special site survey of US congress in 1979. Rockness et al. (1986) failed to report statistical significant relation of environmental performance to financial performance. After 1980’s, researchers adopted more advanced measures for both environmental performance and financial performance. They were also enabled to use more advanced statistical techniques. Studies in 1990’s generally employed cross sectional or pooled regression to analyse environmental and financial performance while in next decade panel data dominated the research (Horváthová, 2012). Using cross sectional regression, Russo and Fouts (1997) extended knowledge from the resource-based perspective examining a broader measure of environmental performance and their effect on return on assets. For environmental performance, they used an independent rating developed by Franklin Research and Development Corporation (FRDC). Although they failed to account for some omitted variables and market based performance, they still found a strong relationship between environmental and economic performance, particularly when including the moderating role of industry growth. Hart and Ahuja (1996) employed multiple regression analysis to analyse environmental performance of companies from 1989 to 1992. Environmental performance variable was drawn from Investor Responsibility Research Centre (IRRC) Corporate Environmental Profile. Hart and Ahuja (1996) illustrated two ways to decrease pollution in order to comply with environmental regulations. Their study assessed environmental 6 performance using accounting based financial performance measures. They suggested that firms can improve environmental performance by (i) control: emissions and wastes are trapped, stored, treated and disposed of using pollution control equipment; or (ii) prevention: emissions and wastes are reduced, changed or prevented altogether through better housekeeping, material substitution, recycling or process innovation. They found that pollution reduction initiatives are positively related to operating and financial performance measures over a two-year horizon. Firms that made the largest improvements in environmental performance experienced the most profound economic gains. Garber and Hammitt (1998) examined the effects on costs of equity for 73 chemical firms with identified Superfund6 liabilities. They found no relationship between the liabilities and cost of equity for small firms, but they were able to find a robust positive relationship for 23 large firms. Nehrt (1996) investigated the timing and investment intensity in low pollution producing paper & pulp manufacturing technology. He used chemical bleach (chlorine gas or chlorine dioxide) which is a critical chemical in textile industry as environmental performance variable. The research shows that firms having earlier investments in less pollution emitting technologies experienced higher levels of growth in profit. Wahba (2008) analysed 153 Egyptian companies from 2003-2005. He used ISO 14001 awards as a proxy to measure environmental responsiveness. Using random effect regression, Wahba (2008) concludes that firm having more environmental responsiveness have higher market value. ISO awards are also used in event studies. For example, Francia Ayerbe (2009) analysed investor response to ISO 14001 awards by conducting event study. They find that company financial performance declined on the date of announcement of ISO 14001 awards. Klassen and McLaughlin (1996) tried to find a link between environmental 6 Superfund program was established in United States under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA) and amended by the 1986 Act of Superfund Amendments and Reauthorization Act (SARA). It is the program to clean up the US uncontrolled hazardous waste sites. US environmental protection agency is committed to ensure that remaining National Priorities List hazardous waste sites are cleaned up to protect the environment and the health of all US citizens (Garber & Hammitt, 1998). 7 performance awards winning companies and their financial performance. Market prices were taken as a proxy for stakeholder response under the assumption of the efficient market hypothesis 7 . It was found that firms receiving environmental performance awards and increased positive publicity were experiencing higher market value, while negative publicity had the opposite effect. Since the efficient market hypothesis is challenged (Brown, 2011), Events studies are criticised for having a short time window. It also ignores the importance of any other information on stock prices during the study period. Apart from ISO awards, there are some other event studies in the corporate environmental performance literature that investigated environmental effects on firm financial performance. Among these, the well cited study of Hamilton (1995) investigated the effects of the first Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) announcements of 1989 on firm financial performance. This event study finds that firms suffered average stock market losses of $4.1 million on the day after negative Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) announcements. It is also established that investors take TRI as news and takes it into account when making investing decisions. Yamashita, Sen, and Roberts (1999) also conducted event study methodology and find that companies with weak environmental consciousness score underperform as compared to companies that have strong environmental consciousness in long term. Busch and Hoffmann (2011) find results similar to Hamilton (1995), that firms who had been the target of Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) investigations and those who had appealed enforcement actions lost market value when these outcomes were announced. Using portfolio analysis, Diltz (1995) analysed 28 common stock portfolios from 1989-1991. He concludes that ethical screens, good environmental performance and lack of nuclear industry involvement enhances portfolio alpha. Gottsman and Kessler (1998) conclude that portfolios having more environmentally responsible stocks out-perform 7 Majority of event studies assume that financial market has strong form of efficiency. They also ignore other factor that may influence their analysis (Busch & Hoffmann, 2011). 8 S&P500 index and poor environmentally common stocks portfolio underperform the index. Contrarily Cohen et al. (1997) argued that investors making investment in green portfolio is not receiving any premium compared to those investors that invest in environmentally poor portfolios. Similarly, Filbeck and Gorman (2004) analysed the environmental performance of electric utilities companies from S&P500 markets. Their study used Investor Responsibility Research Center (IRRC)’s 2000 Corporate Environmental Profiles Database (CEPD) for environmental performance and investor holding period yield for financial performance. They also failed to find any difference between less compliance companies and more compliance companies in electric utility sector portfolios. Considering heterogeneity in the extant literature, several researchers employed different estimation models to analysed environmental performance and financial performance association and evident different results. King and Lenox (2001) have assessed 652 US firms from manufacturing sector during 1987-1996. They measured environmental performance as log of gross toxic chemical emission. Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression shows some association between market based financial performance and environmental performance but the direction of this association is uncertain and contingent. They further suggest that this association may be caused by firm unobserved specific effects and strategic position. Later on, King and Lenox (2002) evident positive association between total emission and future financial performance when they used fixed effect regression and controlled for firm unobserved specific effect. Similarly, Telle (2006) finds a positive association between environmental performance and financial performance using OLS regression. But he finds no association after random effect regression. Telle (2006) concludes that such erroneous and inconsistency in results arises because of omitted variable bias. Salama (2005) compared OLS and robust median regression results for United Kingdom based companies. As the median regression analysis is more robust to the presence 9 of firm unobserved heterogeneity and outliers therefore, the study shows stronger results compared to OLS. Elsayed and Paton (2005) compared pooled, cross sectional, static and dynamic panel data analysis using UK 227 firms from 1994-2000. Environmental performance measure is taken from Management Today survey which is a community and environmental responsibility score for the Britain’s most admired companies. A study by Elsayed and Paton (2005) showed no association between environmental performance and financial performance using dynamic and static models. Whereas, there is strong positive relationship using cross sectional and pooled regressions. 3 Data and Methodology In the following section, we describe the data used to analyse the effect of environmental performance on financial performance. The yearly frequency data is used for both dependant and independent variables. 3.1 Data and Measurement: 3.1.1 Financial Performance Previous empirical works have used several measures of financial performance. These measures include return on assets, return on equity, return on sales and Tobin’s Q. We are using two measures, returns on assets and Tobin’s Q for our study. The return on assets ratio is expressed in the form of a percentage. This accounting measure of profitability has significant importance because it shows the effective and efficient use of firm total assets to generate earnings (Cohen et al., 1997; Horváthová, 2012). In other words, return on assets shows the amount of profit a firm generates for each unit of investment in assets (Palepu et al., 2010). There is slightly variation in formulation of this measure in the literature. We adopt Palepu et al. (2010) measure of ROA: 10 𝑅𝑂𝐴 = 𝐸𝑎𝑟𝑛𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝐵𝑒𝑓𝑜𝑟𝑒 𝐼𝑛𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑒𝑠𝑡 𝑎𝑛𝑑 𝑇𝑎𝑥(𝐸𝐵𝐼𝑇) 𝐴𝑣𝑒𝑟𝑎𝑔𝑒 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝐴𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 Similarly, Tobin’s Q is measure of firm financial performance when analysing more abstract phenomenon. It measures the market value of a firm relative to the replacement cost of its assets. In other words, it is the intangible assets market worth in the form of tangible assets (Chung & Pruitt, 1994). Following Guenster, Bauer, Derwall, and Koedijk (2011) and Perfect and Wiles (1994), we compute Q as the total market value of firm’s assets divided by the book value of firm assets. 𝐴𝑝𝑝𝑜𝑥𝑖𝑚𝑎𝑡𝑒 𝑄 = 𝑀𝑉𝐴 + 𝑃𝑆 + 𝐷𝑒𝑏𝑡 𝑇𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝐴𝑠𝑠𝑒𝑡𝑠 Where MVA is the product of a firm’s share price and the number of common stock outstanding, PS is the product of firm’s preferred stock price and number of preferred stock outstanding. The simplified procedure involved in the calculation of Q shows a compromise between analytical precision and calculation efforts. The true measure of any such simplification technique is its degree of accuracy when compared with values obtained from following the theoretical more correct model (Chung & Pruitt, 1994). However, Perfect and Wiles (1994) found 0.9856 observed correlation between simplified Q with Lindenberg and Ross (1981) Q through empirical investigation of 62 firms. Thus, simple estimation of Q is continued to be a useful measure of financial performance (Chung & Pruitt, 1994). All financial data are obtained from commercial firm database DATASTREAM. The database maintain firms’ majority of information from statement of income and balance sheet items. 3.1.2 Environmental performance (EnvPer) Environmental performance measures vary in previous studies. Quantitative measurement of Environmental Performance (EP) by companies is a difficult task. The most 11 challenging part is the development of a reliable proxy that is widely accepted. This challenge has been well documented in the literature by Ilinitch, Soderstrom, and Thomas (1998). To date, there is no uniform environmental performance definition accepted by a range of stakeholders. In recent years, significant progress has been made to define environmental performance construct both theoretically and empirically. Some of extant literature used different ratings to measures environmental characteristics. These rating include Kinder, Lydenberg & Domini (KLD), Corporate Environmental Data Clearinghouse (CEDC) and Ethical Investment Research Services (EiRiS). KLD is a private consulting organisation that keeps records for 9 areas of environmental and social performance of firms (KLD Research & Analytics, 2003). Corporate Environmental Data Clearinghouse (CEDC) collects data for over 700 companies including the S&P500 firms. Firms’ social and environmental performance is measured using 11 objective criteria and published in a report ‘SCREEN’ (Gerde & Logsdon, 2001). Ethical Investment Research Services (EiRiS) provides its independent services to different investors on corporate environmental, social and governance (ESG) related issues. It keeps record of ethical performance indicators for 3,000 companies globally (EIRIS Foundation, 2012). Apart from these ratings, other qualitative and quantitative proxies are also used to measure corporate environmental performance. For example, environmental certificates like ISO-14001 (Ann, Zailani, & Wahid, 2006; Paulraj & Jong, 2011; Wahba, 2008), perceptual measures like environmental strategy (Sharma & Vredenburg, 1998), environmental competitive advantages (Karagozoglu & Lindell, 2000), environmental management practices (Carmona-moreno & Cééspedes-lorente, 2004; González-benito & González-benito, 2005) and integration of environmental performance issues into strategic planning process (Judge & Douglas, 1998). These performance measures are not common across all countries and are influenced by the overall business, social and legal environment of respective countries. The 12 desire to have a similar environmental database is fulfilled after the United Nation Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) at Rio de Janeiro in 1992, where countries agreed to maintain industrial chemical emission data on specific substances that have potential risk to the environment and public health (Fenerol, 1997). Later on, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), in cooperation with the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) and the United Nations Environment Program developed and maintained the first Pollutant Release and Transfer Register database (PRTRs, 2012). This database maintains records of chemicals released to the environment. Different countries use different nomenclatures for PRTRs. For example, the National Pollutant Inventory (NPI) in Australia, the Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) in the United States, the Pollutant Emission Register (PER) in the Netherlands, and the National Pollutant Release Inventory (NPRI) in Canada. According to the OECD Council Recommendation C(96)41/FINAL, as amended by C(2003)87, the core objectives of a PRTR system are to group substances that have a harmful impact on humans and the environment, report its source on periodic basis preferably annually and make it available to different stakeholders including community and workers (PRTRs, 2012). In Australia, the PRTR is maintained under the Ministry for Environment and Heritage with the name of National Pollutant Inventory. It collects over 90 chemical from majority of factories in Australia. Few studies have used these databases in their studies. For example, Al-Tuwaijri et al. (2004) used toxic waste recycled to total toxic waste generated for their study using TRI. The problem with such ratio is that it ignores the dangerousness of each chemical emitted by the company. In most recent study Horváthová (2012) has tried to overcome this problem. He calculated environmental performance by dividing each toxicant to its threshold using PRTR for Czech Republic. He argues that as each chemical threshold is set up according of its 13 dangerousness therefore, it represent the harmfulness of each toxicant. He used chemicals with above threshold emission whereas in practice company may have emission for a chemical that is under threshold level. This study goes one step further and adopts environmental performance index discussed by Muhammad and Scrimgeour (2012). This robust formulation for making index is not used by existing studies. The most important aspect of such formulation is that it caters for the harmfulness from three different aspects (environment, human health and exposure). The cumulative impact of these three dimensions is called environmental risk score. This risk score is then multiplied with each of the emitted chemical level of emission called Weighted Average Risk (WAR) for respective chemical. This process is repeated for all emitted chemicals for a given facility and finally added up to form facility level WAR (Muhammad & Scrimgeour, 2012). 93 WAR𝑓 = ∑ 𝑅𝐹𝑖 ∗ 𝐸𝑖 𝑖=1 Where: WARf Weighted Average Risk for a facility RF = (𝐸𝑛𝑣𝑖𝑟𝑜𝑛𝑚𝑒𝑛𝑡 𝐸𝑓𝑓𝑒𝑐𝑡 + 𝐻𝑢𝑚𝑎𝑛 𝐻𝑒𝑎𝑙𝑡ℎ 𝐸𝑓𝑓𝑒𝑐𝑡)𝑋 𝐸𝑥𝑝𝑜𝑠𝑢𝑟𝑒 E Emission in kg of a given substance to environment in a year If a company has more than one facility, WAR is added up to form company level WAR. To normalise the weighted average risk of company, we divided WAR by total assets of the company (EnvPer). 14 3.1.3 Environmental Concern We include environmental concern in our model as predetermined phenomenon. Ullmann (1985) emphasised on the inclusion of management strategy in models analysing the company social responsibility. Telle (2006) in his study concluded that the firm positive environmental performance is probably because of omitted variable bias. This is also consistent with Al-Tuwaijri et al. (2004) who included variables for environmental concern in their study. We use three variables for environmental concern. The first variable is firm Crisis Management System (CMS). If a company report on crisis management systems or reputation disaster recovery plans to reduce or minimize the effects of reputation disasters, we code CMS 1 otherwise it is coded as 0. The second environmental concern characteristic is Environmental Supply Chain Management (ESCM). If the company use environmental criteria (ISO 14000, energy consumption, etc.) in the selection process of its suppliers or sourcing partners, then ESCM is coded as 1 otherwise it is coded 0. The last measure, Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability Committee (CSRSC), is a coded 1 if the company have a CSR committee or team otherwise it is coded 0. As companies have the discretion to involve in these activities therefore, this study considers it as top management concern for environment. 3.1.4 Environmental Image Al-Tuwaijri et al. (2004) claim that firms having greater public visibility are exposed to high political cost for poor environmental performance. Therefore, high visible firms are having high standards for environmental performance. Firms having better environmental management systems, products or services normally used it in its promotional campaign that they are more environmental responsible or green concern. Hence, we control for the environmental image propagation by company. We use two variables to measure this phenomenon. The first environmental image variable is ISO-14000 certification. Companies claim to have ISO certification during their promotional campaign. ISO-14000 certification is 15 used as environmental responsible/green symbol. If company is ISO certified it is coded 1 otherwise it is coded 0. The second variable is Environmental Management Team (EMTeam). If the company reports an environmental management team, then it is coded 1 otherwise 0. These all variables are taken from DATASTREAM database and counterchecked with company annual reports. We selected all company that report data to NPI and are listed on Australian Stock Exchange (ASX) from 2005-2006. Our final sample includes 76 companies from different sectors. The summary of statistics is presented in Table 1. 3.2 Econometric Model There are several studies that have analysed firm financial and environmental relationship by simple correlation coefficients (Jaggi & Freedman, 1992; Orlitzky, 2001). The objection on these studies are on the positive sign of the correlation as it may be due to the confounding variable (Orlitzky, 2001; Telle, 2006). A number of studies have overcome this problem and analysed firm financial performance and environmental performance by regression analysis where they accounted for firm heterogeneity. Following literature, we also estimated following generic model for both dependant variables (ROA and Tobin’s Q) Model_1 𝐹𝑃𝑖𝑡 = 𝛼 + 𝑏𝐸𝑁𝑉𝑖𝑡 + 𝑑𝑋𝑖𝑡 + ɛ𝑖𝑡 (1) Where FP is the firm financial performance, ENV is environmental performance, X is vector of control variables, ɛit is error term. Here α is constant, b and d are vector that capture the marginal effect of environmental performance and control variables respectively. i=1,2,…,N cross sectional unit (companies) for periods t=1,2,…..,T. In Model_1, we control for several apparent relevant factors. These factors include environmental concern, environmental image and previous year weighted average emission of the company. Despite of these control variables, omitted unobserved variables could still 16 be the primary reason for the estimated coefficients effects. Therefore, Model_1 may produce bias and inconsistent estimates. This problem may be overcome by including omitted variable to estimated model. According to Telle (2006) good quantitative data is sometimes unavailable to include omitted variable e.g quality of management. He further suggests that instrumental variable may be applied to overcome omitted variable bias. A valid instrumental variable would be the one that is correlated with environmental performance variable and uncorrelated with the error term or omitted variables which itself is very difficult task (Telle, 2006). To address this issue, we control for unobserved firm characteristics. This could be done either random or fixed effect regression estimates. In cross-sectional random and fixed effect approach the error term is divided into unit-specific error (λi), which is not changing over time (firm specific) and an idiosyncratic error (µi), which is observation specific (varies over unit and time). If we add (λi) to the intercept (α), this model is called cross-sectional fixed effect model (Model_2). We assume that each unit (firm) has a constant individual specific effect that shifts the dependant variable by fixed magnitude. Generic estimation of Model_2 is as follows. 𝐹𝑃𝑖𝑡 = (𝛼 + 𝜆𝑖 ) + 𝑏𝐸𝑁𝑉𝑖𝑡 + 𝑑𝑋𝑖𝑡 +µ𝑖𝑡 (2) In this way we allow each unit (firm) to have different intercept. Whereas, the coefficients for the regression i.e. slopes are still the same. Similarly, for cross-sectional random effect we assume that unit specific error (λi) is random phenomenon and distributed independently of explanatory variables. As a result, λi is treated as part of error term and the Model_3 is estimated as follows. 𝐹𝑃𝑖𝑡 = 𝛼 + 𝑏𝐸𝑁𝑉𝑖𝑡 + 𝑑𝑋𝑖𝑡 + (µ𝑖𝑡 + 𝜆𝑖 ) 17 (3) Equation 2 and equation 3 may not rule out all possibilities of omitted variable bias. After controlling for firm specific effects (cross-sectional effects), we also estimated models to control for time specific effects. In cross-sectional time specific approach the error term (ɛ) is divided into three parts. The first part is individual specific effects which are time invariant (λi), the second part is time specific effects that affect all firm with same magnitude (€t) and the third part is observation specific idiosyncratic (µit). If we add firm specific effects (λi) and time specific effect (€t) to the intercept (α), this model is called cross-sectional time invariant fixed effect model (Model_4). We assume that each unit effect (firm) and time specific (across years) have constant effect that shifts the dependant variable by fixed magnitude. Generic estimation of Model_4 is as follows. 𝐹𝑃𝑖𝑡 = (𝛼 + 𝜆𝑖 + €𝑡 ) + 𝑏𝐸𝑁𝑉𝑖𝑡 + 𝑑𝑋𝑖𝑡 +µ𝑖𝑡 (4) Similarly, for cross-sectional time invariant random effect we assume that unit specific error (λi) and time specific (€t) are random phenomenon and are uncorrelated explanatory variables. As a result, λi and €t are treated as part of error term. Model_5 is estimated as follows. 𝐹𝑃𝑖𝑡 = 𝛼 + 𝑏𝐸𝑁𝑉𝑖𝑡 + 𝑑𝑋𝑖𝑡 + (µ𝑖𝑡 + 𝜆𝑖 + €𝑡 ) 4 (5) Results and Discussion This section presents the results from our estimated models on each of the dependant variable of financial performance. Table 1 presents the basic descriptive statistics for study dependant, independent and control variables. The mean (standard deviation) of first dependant variable which is market based financial performance (Tobin’s Q) is 3.59 (5.84). The mean (standard deviation) of second dependant variable (accounting based financial performance) ROA is 0.16 (31.4) percentage point. The mean (standard deviation) of variable of interest (independent or environmental performance) variable is 153.9 (553.8). This suggests that on 18 average 153.9 units of toxic chemicals are released for every one thousand units of total assets. Table 1 Summary of statistics – Cross sectional data for 76 ASX listed companies Variable Name Mean SD Min Max Tobin's Q (TQ) 3.59 5.84 -1.57 39.7 Return on Assets (ROA) -0.16 31.4 -280 63.8 Environmental Performance (EnvPer) 153.9 553.8 0.01 4668.7 ISO-14000 (ISO) 0.37 0.48 0 1 Crisis Management System (CMS) 0.23 0.42 0 1 Environmental Supply Chain Management (ESCM) 0.32 0.47 0 1 CSR-Sustainability Committee (CSRSC) 0.57 0.50 0 1 Environmental Management Team (EMTeam) 0.41 0.49 0 1 Table 2 present the pairwise correlation results. Independent variable (environmental performance) is negatively correlated to both dependant variables ROA and Tobin’s Q, but the pairwise linear relationship is weak as the coefficients are less than 0.40 level. This result is consistent with prior studies that find mix result (Al-Tuwaijri et al., 2004). Other pair-wise correlations in Table 2 are weak too. None of the estimated correlation represents obvious anomalies to theoretical explanation. Table 2 Correlation coefficients matrix for all variables included in the model. TQ ROA EnvPer ISO CMS ESCM CSRSC TQ 1 ROA 0.233*** 1 EnvPer -0.115** -0.176*** 1 ISO 0.255*** 0.163** 0.0238 1 CMS 0.289*** 0.0960 -0.0379 0.148** 1 ESCM 0.379*** 0.165** -0.146* 0.500*** 0.360*** 1 CSRSC 0.343*** 0.256*** 0.0475 0.236*** 0.233*** 0.357*** 1 EMTeam 0.122* 0.00607 -0.169** 0.235*** 0.343*** 0.346*** 0.303*** EMTeam 1 Notes: (1) * denotes significance at 10% (p<0.10), ** denotes significance at 5% (p<0.05), *** denotes significance at 1% (p<0.01) 19 The regression results are presented in Table 3 (Tobin’s Q) and Table 4 (ROA). Our results in Table 3 show that hazardous chemical emission has an effect on financial performance. Simple OLS (Model_1), cross-sectional random effect model (Model_3) and cross-sectional Table 3 Environmental performance and its impact on market based financial performance (Tobin’s Q) EnvPer ESCM CSRSC CMS ISO EMTeam WAR t-1 Model_1 -0.018*** (-3.09) 4.5831*** (2.74) 0.5694 (0.62) 3.0675** (2.25) 1.4889 (0.97) -0.0872 (-0.08) 0.0010*** (6.71) Model_2 0.0055 (1.28) 3.8769 (1.09) -0.7625 (-0.76) 1.9283 (0.68) -2.4296* (-1.8) 3.3284 (1.44) 0.00021*** (3.32) Model_3 -0.0098** (-2.03) 4.3855* (1.7) -0.063 (-0.08) 2.1066 (1.26) 0.6737 (0.35) 1.5791 (0.89) 0.00010*** (6.38) 2.8553*** (4.31) 153 0.3519 No No Robust 3.9573*** (4.37) 153 0.2375 Yes No Cluster 2.3887*** (4.34) 153 2006.Year 2007.Year 2008.Year 2009.Year 2010.Year Constant N R2 Firm effect Year effect vce Yes No Robust Model_4 0.0151** (2.14) 2.842 (0.83) -1.6253 (-1.4) 1.2497 (0.47) -3.4840** (-2.31) 2.5532 (1.11) 0.0001** (2.11) 1.2284 (1.08) 0.87 (0.84) 3.4959** (2.15) 1.9754 (1.1) 3.9084* (1.82) 3.1992*** (3.05) 153 0.2955 Yes Yes Cluster Model_5 -0.0095* (-1.96) 4.5042* (1.85) 0.2023 (0.24) 2.1657 (1.28) 0.7626 (0.4) 1.6399 (0.94) 0.00015*** (6.01) -0.2698 (-0.23) -1.6393* (-1.68) 0 . -2.5401*** (-2.59) -0.8853 (-1.14) 3.4306*** (4.14) 153 Yes Yes Robust Notes: (1) * denotes significance at 10% (p<0.10), ** denotes significance at 5% (p<0.05), *** denotes significance at 1% (p<0.01); (2) Number in parenthesis below each coefficient show t-statistics time invariant random effect model (Model_5) have positive association between environmental performance and financial performance. Whereas, cross-sectional time invariant fixed effect model (Model_4) has negative effect. These results are similar to King 20 and Lenox (2002) and Elsayed and Paton (2005). Only cross-sectional fixed effect model (Model_2) has showed no association between environmental performance and financial performance. Two of environmental concern variables (Environmental Supply Chain Management (ESCM) and Crisis Management System (CMS)) have positive impact on financial performance in OLS estimation. Environmental Supply Chain Management (ESCM) is weakly significant (p<0.10) in Model_3 and Model_5 as well. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Committee (CSRSC) is the only environmental concern variable that has no impact in any model. Overall, environmental concern has weak or no association with financial performance except in OLS estimation. Environmental image measured by ISO award are significant in cross-sectional fixed effect (Model_2) and cross-sectional time invariant model (Model_4). Whereas, Environmental Management Team (EMTeam) has shown no association with financial performance. Three out of four significant models suggest that overall environmental performance has positive association with market based financial performance. Table 4 presents the results of environmental performance impact on return on asset. Simple OLS in Model_1 shows positive impact of improved environmental performance on ROA. Cross-sectional fixed effect (Model_2) and cross-sectional time invariant fixed effect model (Model_4) have negative effect on improved environmental performance and financial performance this result is align with the finding of King and Lenox (2001). Whereas, crosssectional random effect (Model_3) and cross-sectional time invariant random effect (Model_5) has shown no association between improved environmental performance and accounting based financial performance. Telle (2006) also finds similar results and consider that such erroneous and inconsistency in results is probably because of omitted variable bias. 21 Table 4 Environmental performance and its impact on accounting based financial performance (ROA) EnvPer ESCM CSRSC CMS ISO EMTeam WAR t-1 Model_1 -0.046*** (-4.03) 0.8789 (0.48) 2.1749 (1.21) 0.8943 (0.42) 1.7237 (0.89) -1.9703 (-1.2) Model_2 0.0345*** (3.49) 2.5819 (1.26) 0.0419 (0.03) -3.7172 (-1.47) -8.3353*** (-3.52) -1.6782 (-0.74) Model_3 -0.0219 (-0.96) 2.1467 (1.28) 1.3081 (0.78) -2.0258 (-0.83) -0.5333 (-0.17) -1.9236 (-0.85) Model_4 0.0304** (2.39) 3.2009 (1.25) 0.4519 (0.26) -3.5901 (-1.4) -7.6713** (-2.62) -1.3145 (-0.53) Model_5 -0.0227 (-1.3) 3.6196* (1.74) 3.1114* (1.74) -0.5766 (-0.21) -0.3679 (-0.14) -0.3977 (-0.17) 0.000031*** (3.34) 0.000015 (0.48) 0.000011 (1.58) 7.8063*** (4.58) 152 0.1334 No No Robust 11.4950*** (10.63) 152 0.1133 Yes No Cluster 8.0378*** (3.51) 152 0.00001 (0.57) (-0.94) -1.6465 (-0.94) -1.0975 (-0.55) -1.7084 (-0.64) -2.8419 (-0.87) -1.4966 (-0.48) 12.4035*** (9.45) 152 0.1234 Yes Yes Cluster 0.0000012 (1.6) (-1.32) -2.4463 (-1.32) -3.4773* (-1.71) -5.6142** (-1.98) -7.8010** (-2.47) -7.4626*** (-2.66) 11.7695*** (5.91) 152 2006.Year 2007.Year 2008.Year 2009.Year 2010.Year Constant N R2 Firm effect Year effect vce Yes No Robust Yes Yes Robust Notes: (1) * denotes significance at 10% (p<0.10), ** denotes significance at 5% (p<0.05), *** denotes significance at 1% (p<0.01); (2) Number in parenthesis below each coefficient show t-statistics Environmental concern measured by Environmental Supply Chain Management (ESCM) and Corporate Social Responsibility & Sustainability Committee (CSRSC) have association with financial performance at 10% level in Model_5. Environmental image measure by ISO awards has negative impact in Model_2 and Model_4. Environmental Management Team has 22 no association in any of the observed models. Apart from OLS results, fixed effect models suggest that environmental performance depresses accounting based financial performance. Since panel data analysis is used therefore, it is possible that observations contain intra-firm correlations. To avoid the effect of these correlations, the models used in this study provide results using robust standard errors cluster by company. We performed Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) test to check whether two or more variables are having linear combination with one another. It is important because if observed model estimates and coefficients are unstable then standard error of coefficients is also inflated many folded. All variables’ VIF values are less than 10 meaning that there is no relationship among independent variables. This level of VIF is considered to be the conventional rule of thumb (O’Brien, 2007). 5 Conclusion This study investigates the association between environmental performance and financial performance. After considering unobserved firm effects and time variant effects (which is also in direction with Al-Tuwaijri et al. (2004), Telle (2006) and (Ullmann, 1985) argument that the execution of corporate environmental performance is determined by corporation overall strategy (unobserved effects)) and applying new empirical proxy for environmental performance, this study finds that there is a strong association between environmental performance and financial performance. Only two models results are consistent in both accounting based and market based financial performance. The first model is OLS that suggest positive association (p<0.01) and second model is cross sectional time invariant fixed effect model that suggest negative association (p<0.05). From market based financial performance perspective, overall random effect model find a positive significant effect of environmental performance. Whereas, in accounting based financial performance, fixes effect model find negative significant association. These results 23 are important for investors and managers. Manager should have least concern for the depressed accounting performance as it overall suggests that environmental performance depresses accounting number but at the same time, investors interpret it as a source of information and value it as factor that improve corporate market value. Future research should focus on inclusion of more relevant unobserved factors. If more than one variable are used for a single category of unobserved variable, then factor analysis can be used to combine more than one variable to form a single category for control variable. While analysing environmental performance and financial performance nexus, future research can utilize econometric models to seek the general concern of causality. Providing different theoretical basis to corporate environmental performance will also add knowledge to existing literature. 24 6 References Abbott, W. F., & Monsen, R. J. (1979). On the measurement of corporate social responsibility: Self-reported disclosures as a method of measuring corporate social involvement. Academy of Management Journal, 22(3), 501-515. Al-Tuwaijri, S., Christensen, T. E., & Hughes, H. E. (2004). The relations among environmental disclosure, environmental performance, and economic performance: a simultaneous equations approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29, 447471. 10.1016/S0361-3682(03)00032-1 Ambec, S., & Lanoie, P. (2008). Does it pay to be green ? A systematic overview. Academy of Management Perspectives, 45-62. Ann, G. E., Zailani, S., & Wahid, N. A. (2006). A study on the impact of environmental management system (EMS) certification towards firms' performance in Malaysia. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 17, 73-93. 10.1108/14777830610639459 Australian Accounting Standard Board. (2004). Framework for the preparation and presentation of financial statements.: Retrieved from http://www.aasb.gov.au/Aboutthe-AASB/The-standard-setting-process.aspx. Bragdon, J. H., & Marlin, J. (1972). Is pollution profitable? Risk Management, 19(4), 9-18. Brown, S. J. (2011). The efficient markets hypothesis: The demise of the demon of chance? Accounting and Finance, 51, 79-95. 10.1111/j.1467-629X.2010.00366.x Busch, T., & Hoffmann, V. H. (2011). How hot is your bottom line? linking carbon and financial performance. Business and Society, 50, 233-265. 10.1177/0007650311398780 Cañón-de-Francia, J., & Garcés-Ayerbe, C. (2009). ISO 14001 Environmental Certification: A Sign Valued by the Market? Environmental and Resource Economics, 44, 245-262. 10.1007/s10640-009-9282-8 Carmona-moreno, E., & Cééspedes-lorente, J. (2004). Environmental strategies in spanish hotels : contextual factors and performance. The Service Industries Journal, 24, 101130. Chen, K. H., & Metcalf, R. W. (1980). The relationship between pollution control record and financial indicators revisited. The Accounting Review, 55(1), 168-177. Chung, K., & Pruitt, S. (1994). A simple approximation of Tobin's q. Financial Management, 23(3), 70-74. 25 Cohen, M. A., Fenn, S. A., & Konar, S. (1997). Environmental and financial performance: Are they related? WP Vanderbilt University. 40 pp. Cordeiro, J. J., & Sarkis, J. (1997). Environmental proactivism and firm performance: Evidence from security anayst earning forecastes. Business Strategy and the Environment, 6, 104-114. Delmas, M., & Blass, V. D. (2010). Measuring corporate environmental performance: the trade-offs of sustainability ratings. Business Strategy and the Environment, 19, 245260. 10.1002/bse Diltz, J. D. (1995). The private cost of socially responsible investing. Applied Financial Economics, 5(2), 69-77. EIRIS Foundation. (2012). EIRIS Empowering Responsible Investment Retrieved from http://www.eiris.org Elsayed, K., & Paton, D. (2005). The impact of environmental performance on firm performance: static and dynamic panel data evidence. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 16, 395-412. 10.1016/j.strueco.2004.04.004 Fenerol, C. (1997). PRTRs: A Tool for Environmental Management and Sustainable Development. PRTR Workshop for the America's SAN Juan del Rio, Maxico. Filbeck, G., & Gorman, R. F. (2004). The relationship between the environmental and financial performance of public utilities. Environmental and Resource Economics, 29, 137-157. Garber, S., & Hammitt, J. K. (1998). Risk premiums for environmental liability: Does superfund increase the cost of capital? Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 36, 267-294. 10.1006/jeem.1998.1046 Gerde, V. W., & Logsdon, J. M. (2001). Measuring environmental performance: use of the toxics release inventory (TRI) and other US environmental databases. Business Strategy and the Environment, 10, 269-285. 10.1002/bse.293 Gilley, K. M., Worrell, D. L., Iii, W. N. D., & Jelly, A. E. (2000). Corporate environmental initiatives and anticipated firm performance: The differential effects of process-driven versus product-driven greening initiatives. Journal of Management, 26, 1199-1216. 10.1177/014920630002600607 González-benito, J., & González-benito, O. (2005). Environmental proactivity and business performance: An empirical analysis. Omega, 33, 1-33. Gottsman, L., & Kessler, J. (1998). Smart screened investments: Environmentally screened equity funds that perform. The Journal of Investing, 7(3), 15-24. 26 Guenster, N., Bauer, R., Derwall, J., & Koedijk, K. (2011). The Economic Value of Corporate Eco‐Efficiency. European Financial Management, 17(4), 679-704. Hamilton, J. T. (1995). Pollution as News: Media and Stock Market Reactions to the Toxics Release Inventory Data. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 28, 98-113. 10.1006/jeem.1995.1007 Hart, S. L., & Ahuja, G. (1996). Does It Pay To Be Green? An empirical examination of the relationship between emission reduction and firm performance. Business Strategy and the Environment, 5, 30-37. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0836(199603)5:1<30::AIDBSE38>3.0.CO;2-Q Horváthová, E. (2010). Does environmental performance affect financial performance? A meta-analysis. Ecological Economics, 70, 52-59. 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.04.004 Horváthová, E. (2012). The impact of environmental performance on firm performance: Short-term costs and long-term benefits? Ecological Economics, 84, 91-97. Ilinitch, A. Y., Soderstrom, N. S., & Thomas, T. (1998). Measuring corporate environmental performance. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 17, 383-408. 10.1016/S02784254(98)10012-1 Jaggi, B., & Freedman, M. (1992). An examination of the impact of pollution performance on economic and market performance: pulp and paper firms. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 19(5), 697-713. Judge, W. Q., & Douglas, T. J. (1998). Performance implications of incorporating natural environmental issues into the strategic planning process: an empircal assessment. Joumal of Management Studies, 35, 241-262. Karagozoglu, N., & Lindell, M. (2000). Environmental management : Testing the Win-Win Model. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 43, 817-829. Khanna, M., & Damon, L. A. (1999). EPA's voluntary 33/50 program: Impact on toxic releases and economic performance of firms. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 37, 1-25. King, A., & Lenox, M. (2001). Does it really pay to be green ? An empirical study of firm environmental and financial performance. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 5, 105-116. King, A., & Lenox, M. (2002). Exploring the locus of profitable pollution reduction. Management Science, 48, 289-299. Klassen, R. D., & McLaughlin, C. P. (1996). The impact of environmental management on firm performance. Management Science, 42, 1199-1214. 10.1287/mnsc.42.8.1199 27 KLD Research & Analytics. (2003). KLD Rating Data: Inclusive Social Rating Criteria. Lindenberg, E. B., & Ross, S. A. (1981). Tobin's q ratio and industrial organization. Journal of Business, 54(1), 1-32. Mahapatra, S. (1984). Investor reaction to a corporate social accounting. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 11, 29-40. 10.1111/j.1468-5957.1984.tb00054.x Montabon, F., Sroufe, R., & Narasimhan, R. (2007). An examination of corporate reporting, environmental management practices and firm performance. Journal of Operations Management, 25, 998-1014. 10.1016/j.jom.2006.10.003 Muhammad, N., & Scrimgeour, F. (2012, August 30-31 ). Hazardous substances in Australian industries: Risk weighting and trends. Paper presented at the New Zealand Agriculture & Resource Economics (NZARE) Society Nelson, New Zealand. Narver, J. C. (1971). Rational management responses to external effects. Academy of Management Journal, 14(1), 99-115. Nehrt, C. (1996). Timing and intensity effects of environmental investments. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 535-547. 10.1002/(SICI)10970266(199607)17:7<535::AID-SMJ825>3.0.CO;2-9 O’Brien, R. M. (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & Quantity, 41(5), 673-690. Orlitzky, M. (2001). Does firm size confound the relatioship between corporate social performance and firm financial performance? Journal of Business Ethics, 33(2), 167180. Palepu, K. G., Healy, P. M., Bernard, V. L., Wright, S., Bradbury, M., & Lee, P. (2010). Business analysis & valuation: using financial statements (4ed.): Cengage Learning. Paulraj, A., & Jong, P. D. (2011). The effect of ISO 14001 certification announcements on stock performance. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 31, 765-788. 10.1108/01443571111144841 Perfect, S. B., & Wiles, K. W. (1994). Alternative constructions of Tobin's q: An empirical comparison. Journal of Empirical Finance, 1(3), 313-341. PRTRs. (2012). Pollutant Release and Transfer Register, . Retrieved from http://www.prtr.net/en/ Rockness, J., Schlachter, P., & Rockness, H. O. (1986). Hazardous waste disposal, corporate disclosure, and financial performance in the chemical industry. Advances in Public Interest Accounting, 1(1), 167-191. 28 Russo, M. V., & Fouts, P. A. (1997). A resource-based perspective on corporate environmental risk management and profitability. The Academy of Management Journal, 40, 534-559. Salama, A. (2005). A note on the impact of environmental performance on financial performance. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 16(3), 413-421. Sharma, S., & Vredenburg, H. (1998). Proactive corporate environmental strategy and the development of competitively valuable organizational capabilities. Strategic Management Journal, 19, 729-753. Spicer, B. H. (1978). Investor, corporate social performance and information disclosure: An empirical study. The Accounting Review, 53, 94-111. Telle, K. (2006). “It Pays to be Green” – A Premature Conclusion? Environmental and Resource Economics, 35, 195-220. 10.1007/s10640-006-9013-3 Ullmann, A. A. (1985). Data in search of a theory : A critical examatination of relationship among social performance, social disclosure, and economic performance of U. S. firms. The Academy of Management Review, 10, 540-557. Waddock, S. A., & Graves, S. B. (1997). The corporate social performance-financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal, 18, 303-319. Wahba, H. (2008). Does the market value corporate environmental responsibility? An empirical examination. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 15, 89-99. 10.1002/csr Watson, K., Klingenberg, B., Polito, T., & Geurts, T. G. (2004). Impact of environmental management system implementation on financial performance: A comparison of two corporate strategies. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal, 15, 622-628. 10.1108/14777830410560700 Yamashita, M., Sen, S., & Roberts, M. C. (1999). The rewards for environmental conscientiousness in the US capital markets Journal of Financial and Strategic Decisions, 12(1) 29