C. Johan Alexis Ortiz Hernández and his death on February 15, 1998

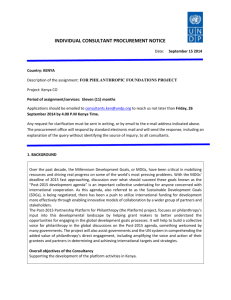

advertisement