Horizons of possibility: ethnographic insights into parent

advertisement

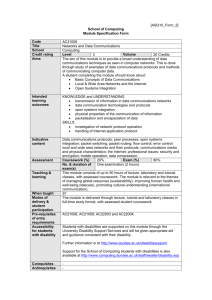

Cassandra Hartblay Masters Candidate, Predoctoral Student Department of Anthropology University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill SDS 2011 Presentation Draft Text Horizons of possibility: ethnographic insights into parent-activist strategies in contemporary Russia What kinds of possibilities exist for parent activists working to create a more inclusive world for children with disabilities in Russia today? How do the specificities of the postsoviet context impact the horizons of possibility for these parent activists? How do postsoviet cases illuminate issues that resonate with disability studies more broadly? [Image: MAP OF RUSSIA] I. The Soviet Union, although hailed worldwide for its accomplishments in national education, did not offer special education of any kind in its schools. Through 1991, children who were deemed unable to participate in classroom learning were simply excluded from educational opportunity. Particularly in the Soviet context, wherein being a good worker defined the good citizen, this lack of educational opportunity meant extraordinary stigma not only for the child, but also for the parents, whose productive capacities were put on the line when a child was reject from schooling. A vast system of decentralized regional institutions and internati (residential rehabilitative facilities) were the states’ solution. With the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, mothers around Russia began to vocally and visibly refuse this system of institutionalization. However, 20 years later in 2011, a federal system of special education has yet to be implemented in public schools. [Image: SOVIET/PS HISTORY TIMELINE] The postsoviet case can be characterized by several qualities that are distinctive in the global context: -industrialized definition of disability aligns with the west, while the political climate (and language of disability) both does and does not (see: Phillips 2009, 2010; Kotkin 2001; Hartblay, forthcoming) - New models for education and inclusion are being brokered on the ground at the grassroots level. The case studies that I relate in this paper indicate three trajectories that these new imaginaries take in one Russian city. As a graduate student equipped with a new research grant, a history of disability ally activism at home, and a background in Russian studies, in the summer of 2010 I embarked on what will become the first of many dissertation research trips to Petrozavodsk, Russia. The city itself is familiar to me, the first place in Russia that I called home, when I lived there for a month as a high school exchange student. In many ways, PZ is an exceptional city: a small regional capital, its residents have a greater access to cosmopolitanism and international ideas than similarly sized cities in more remote regions. PZ, located a day’s bus ride from Finland, or an overnight train ride from Saint Petersburg, is home to one of the most progressive and highly admired regional administrations in Russia; the liberal social democratic influence of its Nordic neighbors evident at every turn. [Image: MAPS SHOWING LOCATION OF PETROZAVODSK] I chose to return to PZ because I had heard through a lobbying listserve that a parent group there had distinguished the region by becoming the first group in the Russian Federation to use the legal rights guarantees of the 1993 constitution to claim inclusive education through the court system. Given the currency of Western debates about rule of law and civil society in postsoviet Russia, the idea of a grassroots movement that had mobilized successful legal outcomes was exciting not only to me as an Anthropologist interested in Disability justice, but also to political scientists, economists, and those concerned with what is commonly referred to as Russia’s transition to democracy. [Image: NEWS ARTICLES REPORTING ON TRIAL OUTCOME] Of course, on the ground, the reality is never as simple as the newspaper story. As I began conducting interviews with community stakeholders in Petrozavodsk, I found that there were several contrasting strategies in play when it came to raising children with disabilities – all of which contributed to deinstitutionalization of citizens with special needs – and only some of which engaged rights-based claims to justice. [Image: PHOTOS OF STAKEHOLDERS] My own background as a peer-advocate and organizer of disability awareness campaigns throughout my secondary and tertiary education in the United States has also buttressed my investigation of similar topics in Russia. Having worked as a peer tutor and paraprofessional in special needs classrooms in US public schools, I approach this work with a certain degree of familiarity with the kinds of challenges, questions, and struggles that arise in educational settings. And having worked as a paralegal for adults seeking disability benefits through the Social Security Administration in Queens County, New York, I have seen and participated in the despondency of bureaucracies of disabilities in the United States, leaving me highly critical of tendencies in mainstream press and some scholarship to pathologize corresponding postsoviet bureaucracies (that is, I do not accept unexamined the idea that the Russian government rules with a dehumanizing iron fist). The particular perspective of disability that I take here takes cues from the particular stance that I take between scholarly literatures. First, as a scholar of disability studies, I am concerned with questions of justice, stigma, and equality as they pertain to bodily and intellectual difference (Linton 1998), to normalcy or hegemony of the center (Davis 2006), and continue to present a challenge to the establishment of a fully functioning liberal democracy in the United States as well as in Russia (Nussbaum 2007). Second, as an interpretive medical anthropologist, I seek to contribute to a body of work that interrogates categories of diagnosis (Young 1995, Lock 1995, Cohen 1998); by juxtaposing the meaning of disability (as a type of difference, and a nexus of economic, medical, and social meanings) in Russia with that in US, I seek to destabilize and defamiliarize both in order to open up new ways of conceptualizing enablement (see: Phillips 2009; Hartblay 2006). Similarly, the anthropology of disability considers the ways that “cultural circumstances (such as assumptions about personhood) and social ones (such as the existence of disability institutions) shape the meaning of disability in different local worlds” (Ingstad and Whyte 2007: 1) so that disability becomes a lens through which to view local subjectivities. I conducted over 15 interviews and observed and visited parents of children with disabilities, teachers of children with disabilities, professionals including social workers and non-profit managers working in relevant fields, doctors, and young adults with disabilities. For the sake of simplicity, I will use the stories of three distinct members of the community to illustrate broader trends, using pseudonyms to protect their privacy. [Image: LIST OF NAMES USED IN CASE STUDIES] Taken together, these case studies suggest the scope of different experiences of families with children with disabilities and the ways that these experiences align with and depart from various expectations of emancipatory progress. II. Nina [Image: DIAGRAM of Nina’s trajectory] Nina is mother to Sveta, who was born in the late 1980s and diagnosed with Cerebral Palsy. Nina was advised by the doctor to institutionalized Sveta and never look back, but she refused, and with the help of her own mother, raised Sveta on her own. In those days, there were no parent networks in Petrozavodsk, and almost no literature on parenting disabled children available in Russia: Nina’s mother spent 40 minutes copying the definition of DTsP (Cerebral Palsy) by hand out of a medical dictionary, which, along with the list of various diagnoses that the hospital handed over when Sveta came home for the first time, was the only information that Nina had. Today, Sveta is a patient, quietly attractive and studious college student in a wheelchair, a far cry from the grotesque permanent child that the doctor predicted. This outcome is due to many factors, chief among them Nina’s stubbornness, as well as several turns of fate. Nina has struggled to find workable solutions to work full time as a high school teacher while negotiating Sveta’s medical, educational, and transportation needs. She doesn’t consider herself an activist, and when asked about progress, her first response is bitter skepticism. Working with other parents is exhausting and stressful she points out, and the federal and regional governments have little interest in acutally making change, rather than occasionally paying lip service to accessibility as a sort of international PR. Lilya [Image: DIAGRAM OF LILYA’S TRAJECTORY] Lilya was born with a series of health problems; over the years she has been able to maintain mobility with the help of a series of operations. Today, a 24 year old journalism student at the regional public university, she walks with a cane, and unlike the majority of her peers, avoids public transportation and gets around in a car – a small sedan dating from the 1980s that has been retrofitted with an apparatus to allow her to control acceleration and braking with her hands. Lilya, as a young teenager, became a beneficiary of the programs that grew out of the parental exchange program in which Nina participated. As a result of that exchange, a local woodshop teacher at the city’s cultural center – where many young people went for after school activities – took up a new initiative to work with youth with disabilities. Tapping ideas emergent from the exchange, the shop teacher, who I will call Oleg, and his wife Nastya, a school teacher, chartered a series of grassroots programs to support kids with special needs and their families. Lilya became one of a group of five youngsters with whom Oleg started an online journal that shared the perspectives of youth with disabilities. The journal was supported with the computer equipment donated to the cultural center during the exchange program, and a few subsequent grants from benefactors in Finland and Germany. Lilya has become a leader amongst her peers in terms of serving as a resource for parents with young children with disabilities. She drops in for visits, provides advice, impromptu childcare, and encouragement. Oleg, with Lilya’s help, organizes a weekly group for families with disabled children. Again with the help of modest foreign grants (rarely for more than a few hundred dollars) they have a “school”, the first floor of a local building, in which the collective gathers on Sundays for tea, lessons, art projects and music lessons, physical therapy and massage for the cerebral palsy kids, and tea and conversation for the parents. The support space, according to Oleg and Lilya is not only about parents supporting one another, but also a space for spurring action. They consider the activity of taking the children for walks or outings to local museums to be one with sociopolitical consequence. “It’s important that people see these kids out and about,” Oleg told me. “How else will we ever make it ok to have a family member with disabilities?” They partner with teachers at local high schools to recruit teenagers to work at a summer camp for the special needs kids. Oleg and Lilya are wary about new mainstreaming initiatives in place in Petrozavodsk. Even if these kids are sitting alongside their peers in classrooms, they point out, it does not mean that they are learning; even with a fulltime facilitator present, integration and education may not occur. Katya [Image: DIAGRAM OF KATYA’S TRAJECTORY] Katya is the leader of the group of amateur parent activists who have partnered with Finnish disability activists and civil rights attorneys to claim a legal right to education in public schools for their children. She has a seven-year-old daughter with DTsP. Prior to Katya & company’s lawsuit, their children – including children who are Deaf, blind, have DTsP and Downs Syndrome – were only able to attend the local rehabilitation center founded by one of Nina’s peers, which accepted children on a rotating three month schedule, meaning that the kids were then left at home all day without services or socialization for long stretches of time, sliding backwards developmentally and placing a burden on mothers to abandon professional work in order to care for them. They won a lawsuit first to include the children in local kindergartens, and subsequently in two primary/secondary schools in the region, allotting a portion of federal development money to sponsoring the integration projects (and thereby keeping the educators on board). Katya recalls that part of their success came from their ability to align their claims with some of the transition rubric that is popular in the area. The turning point in the first lawsuit came when the mothers held a press conference and invited all the local media to come take a look at them and photograph them with their children. The next day, Katya recalls, all the newspapers and local television stations reported that children with disabilities were being left behind in Karelia. This story fit cleanly into what Sarah Phillips has called the “critical discourse” in which disability activism language is harnessed to build on and align with broader conversations about becoming more progressive, more people-first, more rights-based and attendant to rule of law, and generally more like the West. Katya herself is not particularly concerned with this agenda. In addition to wanting better opportunities to her daughter, she has stopped her work as an accountant to pursue activism full time (which is enabled by her husbands’ well-paying job, a situation that would have been unthinkable in the Soviet days, or even in the 1990s when Nina’s daughter was young). Like the “NAMI Mommies” here in the US, who Sue Estroff has pointed out gain a sense of self-worth and a new cultural currency through parentactivism, Katya has taken on the sense of purpose that activism provides. With local partners and Finnish mentors, her group of parents is working to mount new lawsuits to make the city train station more accessible, and they have already successfully sued to make a theater that was under renovation include accessible restrooms and seating to accommodate wheelchair users. III. Given these case studies, let us back up a bit and talk a little bit more about the Russian postsoviet context. -poverty is not a vice [Image: QUOTE FROM CALDWELL 2004] -different dimensions of public/private, autonomy/dependency [Image: GRAPHIC ILLUSTRATION OF AXES OF NEOLIBERAL CITIZENSHIP] -zone of diverse economies and subjectivities, rather than a realm in “transition” toward neoliberal governmentality [Image: DIVERSE ECONOMIES “ICEBERG” (Market Capitalism is just the tip) from Graham 2001)] -continually evolving possibilities for disability activists, although touted by government and Russia transition watchers as successes, do not align neatly with the goals or even yardsticks of success held by outsiders. However, they are successful in finding globally brokered local solutions and transforming lives and human possibility. [Image: QUOTE FROM NEWSPAPER ARTICLES vs. QUOTE FROM NINA] What, then, does this critique of transition discourses call for? Critical scholars of disability studies (Mitchell and Snyder 2010) and of development discourses (Cleaver 1996:236; Esteva; Fraser 1997) have observed that while liberatory movements have traditionally been tied to socialism, increasingly, there is a necessity to look to look not to one political economic form or another (Escobar 1992: 133), but to diverse economies (Gibson-Graham 2006), complex global assemblages (Collier and Ong 2005), and deterritorialized descriptions of local-global spaces (Deleuze and Guattari 1972; Yurchak 2006). In this sense, the way that relationships with local, regional, national, and international resources are brokered by actors on the ground in Petrozavodsk may be illuminating for our considerations of futures, and emancipatory imaginaries that go beyond the tip of the iceberg. [Image: DIVERSE ECONOMIES “ICEBERG” (Market Capitalism is just the tip) from Graham 2001)] Following both critical anthropologists of the postsoviet and critical scholars of disability studies, such as Mitchell and Snyder and Tom Shakespeare (who has critiqued the idea that rights alone, such as the use of civil legal frameworks to claim education, will bring about new justices for people with disabilities and their families) I find in these case studies an opportunity to open new imaginaries of emancipatory projects. By displacing the primacy of neoliberalism and democracy as the yardsticks by which we ought to measure the activities of citizens, or the progress of disability activism, we find more nuanced and rich possibilities that indicate a diversity of potentials that need not align with expected categories and binaries, ideal types or hegemonies of the center. By looking at case studies from the postsoviet context as deterritorialized realities, we approach assumptions about where trajectories of activism lead and what horizons of possibility look like. For Nina and her daughter Sveta, horizons of possibility are not “activism” per se, but transformational change continues to unfold in fits and starts. For Oleg and Lilya, rights-based claims to inclusive education offer new potentialities, but an equal host of new problems, and overshadow numerous grassroots successes. For Katya, activism offers an opportunity to create a new and exciting career that puts her at the forefront of critical political change in her community, brokering cultural capital that extends beyond the direct benefits to her daughter’s educational opportunities, and building international friendships; disability organizing becomes a vehicle by which to push the regional administration toward a people-first politics. None of these trajectories match neatly the binaries of transition discourses. Likewise, the futures they suggest help us to bring postsoviet perspectives into conversations about the diverse nature of emancipatory projects for disability justice. References Andrew Sutton. 1980. Backward Children in the USSR: An Unfamiliar Approach to a Familiar Problem. In Home, School, and Leisure in the Soviet Union, ed. Andrew Sutton, Jenny Brine, and Maureen Perrie. London: Allen & Unwin. Caldwell, Melissa. 2004. Not by bread alone : social support in the new Russia. Berkeley: University of California Press. Escobar, Arturo, and Michael Osterweil. 2010. Social Movements and the Politics of the Virtual: Deleuzian Strategies. In Deleuzian intersections: science, technology, anthropology, ed. Casper Bruun Jensen and Kjetil Rodje. Berghahn Books. Gibson-Graham, J.K. 2006. The end of capitalism (as we knew it) : a feminist critique of political economy. 1st University of Minnesota Press ed., 2006. ed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Graham, Julie. 2001. “Imagining and Enacting Noncapitalist Futures.” Socialist Review 28 (3/4): 93-135. Hartblay, Cassandra. 2006. An Absolutely Different Life: locating disability, motherhood, and local power in rural Siberia. Honors Thesis, Saint Paul, MN: Macalester College, May. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/anth_honors/1/. ———. 2011. A Genealogy of (post-)Soviet Dependency: civil rights or redistribution? In University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, March 11. Hemment, Julie. 2007. Empowering women in Russia : activism, aid, and NGOs. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Iarskaia-Smirnova, Elena. 1997. Sot︡︠siokulʹturnyĭ analiz netipichnosti. Saratov: Saratovskiĭ gos. tekhn. universitet. ———. 1999. “‘What the Future Will Bring I Do Not Know’: Mothering Children with Disabilities in Russia and the Politics of Exclusion.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 20 (2): 66-86. Ingstad, Benedicte, and Susan Whyte. 2007. Disability in local and global worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press. Kohrman, Matthew. 2005. Bodies of difference : experiences of disability and institutional advocacy in the making of modern China. Berkeley: University of California Press. Kotkin, Stephen. 2001. “Modern Times: The Soviet Union and the Interwar Conjuncture.” Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 2 (1): 111-164. Lemon, Alaina. 2008. “Hermeneutic Algebra: Solving for Love, Time/Space, and Value in Putin-Era Personal Ads.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 18 (2): 236-267. Mitchell, David T., and Sharon L. Snyder. 2010. “Disability as Multitude: Re-working Non-Productive Labor Power.” Journal of Literary & Cultural Disability Studies 4 (2): 179-193. Ong, Aihwa. 1988. “The production of possession: spirits and the multinational corporatin in Malaysia.” American Ethnologist 15 (1) (February): 28-42. ———. 2005. Global assemblages : technology, politics, and ethics as anthropological problems. Malden MA: Blackwell Pub. Oushakine, S. 2009. The patriotism of despair : nation, war, and loss in Russia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Phillips, Sarah. 2009. “‘There Are No Invalids in the USSR!’ A Missing Soviet Chapter in the New Disability History.” Disability Studies Quarterly 29 (3). http://www.dsqsds.org/article/view/936/1111. ———. 2011. Disability and mobile citizenship in postsocialist Ukraine. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Rivkin-Fish, Michele. 2005. Bribes, Gifts, and Unofficial Payments: Towards an Anthropology of Corruption in Post-Soviet Russia. In Corruption, ed. Dieter Haller and Cris Shore. Macmillan. Shakespeare, Tom. 2009. Disability: A complex interaction. In Knowledge, Values and Educational Policy: A critical perspective, ed. Harry Daniels. Routledge. Yurchak, Alexei. 2006. Everything was forever, until it was no more : the last Soviet generation. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.