Garbage - TrashEthnography

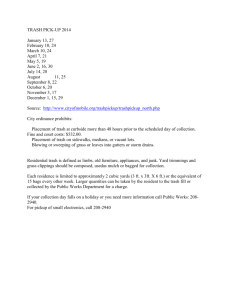

advertisement

Literature review section: The Meaning of Trash and Social Norms Surrounding Waste Disposal Various pieces of academic literature have explored the social meaning of trash, garbage, waste, refuse, or other synonymous terms used to define the items we throw away in both private and public scenarios (Perry et al., 2010; Coverly et al., 2008; Chappells & Shove, 1999; Muller, 2010). Every person has their own rituals or habits regarding trash and how they deal with waste in their day-to-day activities. An analysis of the literature in the field of Garbology yields an exploration into how individuals feel about what they throw out and the habits they develop. Perry et al. (2010) explains that the mechanisms we use to discard our waste are part of a “social phenomenon”, one which involves the discarding of unwanted items, symbolized by an abandonment of ownership and thus any further responsibility for items which are no longer desired. This “social phenomenon” includes various social norms which guide how most people behave when dealing with trash, which defines both legitimate and illegitimate practices. In the context of trash a legitimate practice, especially in public scenarios, is to throw trash into designated bins or cans. Littering, be it passive (e.g. leaving refuse in an area once occupied by an individual) or active (e.g. dropping trash on the ground), also holds meaning as a deviant act against social norms generally reinforced or deterred by peers (Sibley & Liu, 2003). Whether it is an analysis of the social meaning of the kitchen “dustbin” (Chappels & Shove, 1999), an exploration of trends concerning how individuals act around garbage in public areas (Perry et al., 2010), or an examination of the effects non-littering advertisements have on littering behaviours (Sibley & Liu, 2003), it is clear that there are larger social processes involved that guide the way individuals are expected to deal with their waste. Waste, or more specifically waste management, is a reality of all societies and is very much an inevitable consequence of the society in which we live in (Coverly et al., 2008). Waste management is a multifaceted process which truly begins at the trash bin, while for many it ends there as well. Individuals tend to adopt an “out of sight, out of mind” mentality surrounding garbage, as they disband any responsibility or sense of ownership towards an item when it enters a small bin underneath their kitchen sink or a large green trash receptacle in the middle of a park (Coverly et al.). The reality is that this is just the beginning of a long process of dealing with waste; and the garbage bin represents a “gateway between domestic waste arrangements and systems of public provision . . . for most people, contact with the waste industry begins and ends with the [trash bin]” (Chappels & Shove, 1999, p. 198-99). Therefore the trash bin is arguably just as important in its function as it is symbolically significant. The trash bin symbolizes a black hole of sorts, protecting individuals from the evidence of their consumption by hiding their waste. Coverly et al. (2008) explains that the trash bin operates as a transcendent doorway between the visible and invisible aspects of our daily consumption, similar to that of Goffman’s (1971) front and backstage. The by-products of our consumption are frequently hidden in trash cans, representing the backstage, allowing us to engage in more guilt-free consumption in the public, front stage. The trash bin in this case acts as a “smoothing mechanism”, allowing individuals to symbolically cut ties to items they once possessed. Although these items may still lie in a garbage bin under the kitchen sink, they symbolically exit our lives once the waste enters the familiar black hole we call the garbage can. While it is evident that the household or public garbage bin carries symbolic meaning, so too does the practice of disposing waste in socially unacceptable methods, such as littering. There have been several studies that analyze the social meaning of littering, either accidental or intended (Coverly et al., 2008; Sibley & Liu, 2003; Perry et al., 2010; Muller, 2010). While legal sanctions are in place to deal with littering, they are rarely enforced, relying on social sanctions to deal with such deviant behaviour. Perry et al. (2010), in their study of personal trash management in public scenarios, explains: Litter and littering are commonly recognized as both antisocial and illegal. However, the likelihood of being caught littering in the presence of an officer with the legal authority to impose a civil or criminal penalty is low. Although official sanctions are relatively unlikely, social sanctions are more commonly practiced. This can be observed in a variety of what might be considered as morally objectionable activities, in what has been called “uncivil attention”, in which bystanders themselves act to the extent of even physically or verbally abusing people who breach normative patterns of behaviour. (p. 87) Coverly et al. (2008) provides another example of the way we are socialized to believe that the public visibility of waste should be avoided. The authors explain that beginning in childhood we are instructed through environmental campaigns to keep our public areas clean and take responsibility for public waste. Efforts such as the “Keep Britain Tidy” or “Keep America Beautiful” campaigns, which are argued to manage the public awareness of consumption rather than consumption itself, socialize individuals to believe that waste placed in a trash can ceases to be a problem. Litter may not be reacted to so harshly, however, when the activity takes place among a group that have not been successfully socialized to support efforts to maintain public cleanliness. While Muller (2010) found that many teenagers believed throwing litter in the streets is an incivility which undermines the ideal of a clean environment, he also discovered two other common perspectives. He found teenagers also believe: litter does not have much significance and they are therefore indifferent towards litter; or the act of littering is a sign of independence and maturity for teenagers who want to show that they do not care about the norms of the “adult world” (p. 6). Similarly to the findings of Muller (2010), Sibley & Liu (2003) found that smokers are much more likely to litter their cigarettes when they are finished with them than other items such as cups or other packaging materials. The group of smokers studied were also much less likely to positively respond to anti-litter advertisements than non-smokers with non-cigarette litter. This showcases another instance of a certain group of individuals straying away from usual littering norms. While these are two examples of groups within society who do not abide by society’s norms surrounding trash disposal, the literature suggests that individuals commonly dispose of their waste properly due to social pressure or embarrassing consequences they risk enduring if caught littering. Findings/discussion section: Consumer Culture: The Normalcy of Comsumption An analysis of the field notes collected over our two month period yielded dominating accounts of food packaging trash, predominately fast food packaging or the remains of food items packed for the purpose of convenience. It was hard to ignore the reoccurring presence of McDonald’s wrappers, Tim Hortons cups, or chocolate bar wrappers that appear on almost every page of our compiled field notes. This finding was common among each researcher’s work, necessitating a focused investigation into the body of evidence gathered regarding fast food and packaged food consumption. Our society has witnessed the grease-fuelled rise of fast food chains such as McDonald’s, Burger King, KFC. As well, especially so in Canadian culture, there is an increasing demand for coffee shops such as Tim Hortons and Starbucks to provide people with their morning fix of caffeine and possibly a bagel or muffin to fill their stomachs as they rush to work in the morning. One may not realize the dominance of these food chains until they undergo an investigation such as ours, when more often than not a public garbage bin, a table full of trash, or public trails through the woods featured some evidence of our fast food addiction. An example of this was quite apparent during an investigation of trash among a public park in downtown Fredericton: Inside a large green garbage can with a plastic top chained on to it I find a branch, three Tim Horton’s cups, the inside of a gum package that holds single pieces and several small plastic bags. . . The next garbage can I look into has a Poweraide bottle, three more Tim Hortons cups, a Tim Hortons sandwich or bagel wrapper and three tied off plastic bags. . . continuing down the path I see two more Tim Hortons bags used to hold doughnuts or Timbits and a small transparent red liquorice bag beside the trail. In this short period of about one minute an alarming amount of Tim Hortons garbage was observed, both inside of public trash cans and beside park trails. A similar instance was observed near another park which features a trail leading into the woods: As I walk away and head into the woods on I notice to my left there is a lot of garbage scattered throughout the shallow wooded area. In one small section I can count four McDonald’s cups, five lids for cups with straws poked through the tops, a Large McDonald’s bag with food remains inside, two plastic bags from Superstore, a Kit-Kat wrapper, and a Subway cup missing its lid. In this instance the remains of society’s fast food addiction are scattered about in shallow woods along a nature filled walking path, making it painfully obvious that the repercussions of our desire for convenience is not very hard to spot. Schlosser (2001) explains, “The whole experience of buying fast food has become so routine, so thoroughly unexceptional and mundane, that it is now taken for granted, like brushing your teeth or stopping for a red light” (p.3). While it seems that it is commonplace for individuals to enjoy a fast food meal from time to time, we rarely think twice about the subsequent garbage produced at the expense of the speed and convenience of enjoying a Big Mack combo. It seems that while the evidence of our overconsumptive routines can commonly be found on the side of a walking trail, in the bottom of a public trash can, or on the tables, benches, and floors of university campuses, it has not tainted our naive view of the benefits to grab-and-go meals in a fast-paced society. Evidence of the consumer culture we live in can also be observed by the amount of flyers and advertisements that were encountered throughout the field notes. There were numerous occasions where flyers were scattered over tables in the university common areas, stuffed in garbage bins, or laying on the bottom of dumpsters. In one instance, the researcher observed an abundance of flyers and other paper advertisements littered all over the apartment building lobby and filling the only trash can in the area. There are bags of flyers and newspapers sitting underneath a garbage bin mounted on the wall. The function of this bin itself seems painfully obvious. As I look inside the bin I notice all of the flyers that I had gotten in my mailbox yesterday. At the top sits a Canadian Tire flyer, underneath it laid more Greco and Liberal party flyers. As I sift through the bin I notice it is completely filled with flyers, nothing else. It is apparent that as the flyers come in the mail every day, the tenants of the building look at them and then toss them into the bin directly beside the mail boxes. This is just one small example of what Ferrell (2006) refers to as the “culture of endless consumption” (p. 162). It was observed that this small bin is filled up and overflows nearly every day because of the amount of flyers delivered in the mail that are tossed away. While it is hard to blame the tenants of this building for tossing away their flyers to make room for tomorrow’s mail, it showcases yet another example of the unquestioned, but painfully obvious, consumer culture we live in. Other examples regarding the normalcy of consumption were discovered in our field notes when analyzing what people throw away in the trash. In one instance the researcher observed the campus Tim Hortons throwing out all of their baked goods at the end of the day. As the researcher proceeded to buy a pastry before everything was discarded, they counted at least ten muffins that were about to be thrown out, on top of whatever had already been tossed in the trash. While the researcher made a comment to the worker behind the counted about how it is a bit of a waste to just throw everything out at the end of the day, they received a simple and uninterested “mhmm”. This situation exhibited a dynamic of symbolism, in which the muffins that were left over at the end of the day were, for the Tim Hortons worker, trash; but, for the hungry researcher who ended up buying one of the muffins as they were being tossed away, the baked goods represented a product which they saw worthy of buying. To the worker, the process of tossing out muffins and other baked goods at the end of the day was routine for them. However, for the student collecting field notes on garbage, this was an interesting social process that once again displays our “culture of endless consumption”. One minute a muffin is a desired commodity that costs a dollar or two, the next minute it is laying in the bottom of a garbage bag, being taken to the nearby dumpster, deemed worthless. Other discoveries were made that highlight our culture of consumption and consumerism. Inside the garbage hut of one researcher’s apartment building, they discovered a bag full of children’s clothing, shoes, boots, books, and toys—all still in good condition—ready to be sent to the dump. The individual who discarded these items may have done so for various reasons (e.g. the child they once belonged to grew out of the clothes or the parents simply thought they had too much clothes). Regardless of why the prior owners believed they no longer had use for these items, they have fallen victim to our consumer culture, one that is dominated by wants, and less concerned with what we already possess. Ferrell (2006) made similar findings based on his repeated discoveries of discarded items that, while they still held value, they were not kept because of society’s desire for the “next new commodity” (p. 162). He further explains, In this sense, consumer culture creates and sustains among its adherents a soft of existential vacancy—a personal void, a material longing promoted by the same corporate advertisers whose products promise its resolution. But in the same way that consumer culture empties individuals of their identity, it fills their trash bins and Dumpsters with its waste. We can interrogate consumer culture by viewing its advertisement, visiting its engorged shopping malls, even investigating our own closets. We can interrogate it just as well in its aftermath, peering into its packed dumpsters, digging in its trash piles, touring its landfills. (p. 162-63) It appears as though society has created a monster that feeds on material goods and conveniently packaged foods, while collectively ignoring the human snail-trail of waste we all leave behind. Once our trash reaches the black hole that is our home garbage bin or apartment building dumpster, the snail-trail of consumerism has vanished, allowing for the social ignorance of waste to continue. While this all seems quite bleak, we did observe one individual who seemed to be conscious of the waste they produce. One researcher observed a young woman take a small, yet meaningful, stance against our waste producing consumer culture. At 6:51pm, I noticed a blonde haired female wearing a burgundy jacket, hoop earrings, light blue jeans and a grey backpack walks up to the line carrying her reusable Tims mug—a sign that she might be an environmentally friendly individual.. Having worked at Tim Hortons and knowing how the store likes to encourage people to use these types of mugs, the thought of using a reusable mug meant one less cup polluting the environment, so I was happy to see this. This type of environmental consciousness was rarely observed, however it is important to indicate that while the majority of individuals may be naive or unconcerned with the amount of waste they produce, a minority of individuals do exist who actively combat the waste-producing reality of our society’s consumer culture. Chappells, H., Shove, E. (1999). The dustbin: A study of domestic waste, household practices and utility services. International Planning Studies, 4(2),267-280. Coverly, E., McDonagh, P., O’Mally, L., & Patterson, M. (2008). Hidden mountain: The social avoidance of waste. Journal of Macromarketing, 28(3), 289-303. Ferrell, J. (2006). Empire of scrounge: Inside the urban underground of dumpster diving, trash picking, and street scavenging. New York, NY: New York University Press. Goffman, E. (1971). The presentation of self in everyday life. London: Pelican Books. Knussen, C., Yule, F. (2008). “I’m not in the habit of recycling”: The role of habitual behaviour in the disposal of household waste. Environment and Behaviour, 40(5), 683-702. Marshall, G. (1998). Oxford Dictionary of Sociology. Great Britain: Oxford University Press. Perry, M., Oskar, J. & Normark, D. (2010). Laying waste together: The shared creation and disposal of refuse in a social context. Space and Culture, 13(1), 75-94. Schlosser, E. (2001). Fast food nation: The dark side of the all-American meal. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company. Sibley, C. G., Liu, J. H. (2003). Differentiating active and passive littering: A two-stage process model of littering behaviour in public spaces. Environment and Behaviour, 35(3), 415433.