Technical Note – Risk mapping assessment report Draft

advertisement

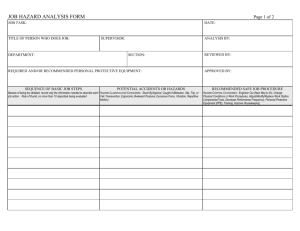

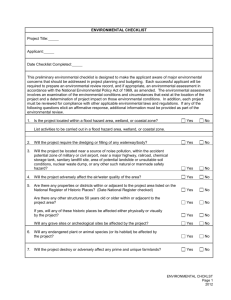

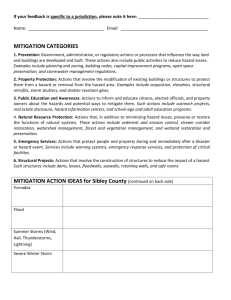

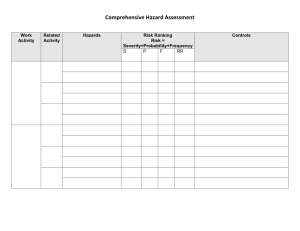

Consultancy Services for Development of Disaster Risk and INSERT YOUR PICTURE (S) inINGhana THIS CELL Early Warning Systems Technical note: Risk Assessment Report UNDP Ghana 30 October 2014 Draft Report BC5721-101-100 HASKONINGDHV NEDERLAND B.V. RIVERS, DELTAS & COASTS Barbarossastraat 35 Postbus 151 Nijmegen 6500 AD The Netherlands +31 24 328 42 84 Telephone +31 24 323 16 03 Fax info@nijmegen.royalhaskoning.com www.royalhaskoningdhv.com Amersfoort 56515154 Document title Technical note 1 October 2014 Document short title Status Date Project name Project number Author(s) Client Reference TN1 Draft Report 30 October 2014 Consultancy Services for Development of Disaster Risk and Early Warning Systems in Ghana BC5721-101-100 Willem Kroonen UNDP Ghana BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm -iTechnical note BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 E-mail Internet CoC CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Goal 1.2 General approach 1.3 Outline 2 FLOOD HAZARD 2.1 Description of methodology 2.2 National flood hazard map current climate 2.2.1 DEM-based hazard mapping 2.3 National Flood hazard map in 2050 2.4 Pilot level map outlook 2.5 Assessment of flood hazard maps 3 3 6 6 8 12 12 3 DROUGHT HAZARD 3.1 Description of methodology 3.2 Application of rainfall deficit-method 3.3 National drought hazard map current climate 3.4 National drought hazard map in 2050 3.5 Pilot level map outlook 3.6 Assessment of drought hazard maps 13 13 14 16 19 24 24 4 VULNERABILITY 4.1 Description of methodology 4.2 Flood vulnerability – situation 2010 4.3 Drought vulnerability – situation 2010 4.4 Vulnerability for future (horizon 2050) 4.5 Vulnerability assessment 26 26 26 30 31 34 5 RISK 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 36 36 36 39 40 41 42 43 6 1 1 1 2 Description of methodology Flood risk Drought risk Future flood risk (horizon 2050) Future drought risk (horizon 2050) Flood Risk assessment Drought Risk assessment LITERATURE 45 - iii Report 1 BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Example of DEM (left) and HAND indexes (right) from Renno et al. (2008) ......3 Figure 2: Validation of the HAND-hazard for the White Volta ............................................5 Figure 3: Validation of the high hazard zone of take Volta with the 84m elevation contour line ......................................................................................................................................5 Figure 4: Validation for the Odaw drain..............................................................................6 Figure 5: Example of the flood hazard map for the national level including large water bodies .................................................................................................................................7 Figure 6: Climate zones and meteorological stations ........................................................9 Figure 7: Flood hazards maps for the A1B and the A2 IPCC climate scenarios .............11 Figure 8: Examples of cumulative rainfall deficit in the Netherlands. ..............................13 Figure 9: Spatial distribution of maximum cumulative rainfall deficit for the years 19982011. .................................................................................................................................15 Figure 10: Spatial distribution of number of dry days ......................................................16 Figure 11: Drought hazard map of Ghana, based on grid data .......................................17 Figure 12: Drought hazard map of Ghana projected on the districts. ..............................18 Figure 13: Boxplot of maximum rainfall deficit within 30-years period for the 22 synoptic stations, for current climate and the 2 climate scenarios A1B and A2. ...........................20 Figure 14: Boxplot of number of days within a year that cumulative rainfall deficit is higher than 600 mm for 30 years period of current climate and A1B and A2 scenario. ..21 Figure 15: Relative increment of numbers of days with rainfall deficit above 600 mm based for climate scenario A1B (left) and scenario A2 (right) .........................................23 Figure 16: Average number of days that the rainfall deficit exceeds the threshold of 600 mm for the current climate, scenario A2 and scenario A1B.............................................23 Figure 17: Drought hazard maps for the A1B (left) and the A2 (right) IPCC climate scenarios ..........................................................................................................................24 Figure 18: Updated land use map with built up areas .....................................................26 Figure 19: Flood vulnerability for 2 alternatives ...............................................................27 Figure 20: Population density and proposed vulnerability ...............................................28 Figure 21: Overall flood vulnerability for 2 alternatives ....................................................29 Figure 22: Drought vulnerability for 2 alternatives ...........................................................30 Figure 23: Example of population growth ........................................................................32 Figure 24: Land use maps for 2010 and 2050 .................................................................32 Figure 25: Population density for 2050 ............................................................................33 Figure 26: Flood and drought vulnerability in 2050 ..........................................................34 Figure 27: Flood risk maps, based on land use alone (alternative 1 on the left, 2 on the right)..................................................................................................................................37 Figure 28: Flood risk maps, based on land use and population density (alternative 1 on the left, 2 on the right) ......................................................................................................38 Figure 29: Drought risk maps for 2 alternatives (alternative 1 on the left, 2 on the right)40 Figure 30: Flood risk maps for 2 climate scenarios for 2050 ...........................................41 Figure 31: Drought risk map for future climate scenarios A1B (left) and A2 (right). ........42 BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - iv Technical note LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Physical meaning of the hazard levels ................................................................ 4 Table 2: Changes in precipitation patterns in the six climate regions of Ghana for the current, A1B and A2 IPCC climate scenarios. ................................................................ 10 Table 3: Overview of district statistics ............................................................................. 12 Table 4: Overview of spatially distributed hazard statistics ............................................ 12 Table 5: Statistics of the spatial distribution of mean (14 years) maximum rainfall deficit [mm]. ................................................................................................................................ 15 Table 6: Definition of drought hazard classification number of days based on the 14 years average value of number of days that cumulative rainfall deficits exceeds threshold of 600 mm. ....................................................................................................... 16 Table 7: Number of days within a year that rainfall deficit is higher than 600 mm, averaged over a 30-years period. For current climate and A1B and A2 scenario .......... 21 Table 8: Same as Table 7, stations averaged over climate zone ................................... 22 Table 9: Same as Table 8, with percentage values. ....................................................... 22 Table 10: Proposed classification for vulnerability based on population density ............ 27 Table 11: Proposed classification for overall flood vulnerability ..................................... 28 Table 12: Flood vulnerability in km2 per alternative, based on land use ....................... 29 Table 13: Flood vulnerability in km2 per alternative, based on population density ........ 29 Table 14: Overall flood vulnerability in km2 per alternative, combining land use and population density ............................................................................................................ 30 Table 15: Drought vulnerability in km2 per alternative ................................................... 31 Table 16: % Area land use in 2010 and 2050 ................................................................. 33 Table 17: Changes In vulnerability between 2010 and 2050 .......................................... 34 Table 18: Value for flood vulnerability ............................................................................. 36 Table 19: Classification from Risk value to Flood Risk ................................................... 36 Table 20: Overview of % of territory of Ghana with a flood risk value for different alternatives ...................................................................................................................... 39 Table 21: Classification from Risk value to Drought Risk ............................................... 39 Table 22: % of territory of Ghana with a drought risk value for 2 alternatives ................ 40 Table 23: Flood risk ......................................................................................................... 43 Table 24: Drought risk ..................................................................................................... 43 -vReport 1 BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Goal The target of this technical report is twofold. Firstly it provides the technical background of the applied methodologies in order to provide the necessary backgrounds to reproduce the maps. Secondly an assessment of the maps is made. This report focusses on the hazard, vulnerability and risk maps at national level. The maps are made for both floods and droughts. Besides the maps for the current situation (current climate) also maps are provided for the future 2050 horizon. These maps are based on two IPCC climate scenarios that are most likely to occur in West-Africa, especially Ghana. The maps are grid based but can also be aggregated to the district level. The maps are input for the more detailed maps that will be produced for the 10 pilot districts which are selected in close corporation with the CREW team. In this report only an outlook is given for the methodology that will be used to make the more detailed pilot maps. This technical note comprises the following information: Description of the methodology Application of the methodology on national level Application of the methodology for future climate (horizon 2050). Assessment of the maps 1.2 General approach The methodology in general is already described in report 1 (reference). This report builds on report 1. It presents the final methodology and makes an assessment of the final maps. Also here we use the following definition: Risk = Hazard x Vulnerability / Capacity This report deals with the mapping of hazard, vulnerability and risk on the national level. The assessment of these parameters is done for two situations: the present one and a future one (horizon 2050). For the hazard mapping the future climate is determined on the basis of the two most likely IPCC climate scenarios. For the vulnerability mapping a socio-economic assessment is used to predict population densities and land used developments in 2050. Risk can be determined on the basis of hazard and vulnerability but should also take the available capacity into consideration as this parameter offers the best possibilities to show risk reduction interventions. Capacity can be increased through technical, institutional and social measures. However, measuring capacity on an objective scale is very difficult and outside the scope of this project. But because we still want to introduce the capacity parameter in the risk assessment, we have chosen to use a relative approach and to take the present capacity as the reference value (100% or 1). This offers the possibility to introduce the effects of capacity-increasing measures for future risk mapping efforts and to show their effects. We intend to introduce the effects of the capacity-increasing measures that are already foreseen in the pilot districts and hot-spot communities (training and early warning system implementation) in the risk mapping on the district level. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 1.3 Outline Because the methodology for hazard mapping differs significantly between flood hazard and drought hazard they are described in two separate chapter, Chapter 2 respectively Chapter 3. Chapter 4 describes the methodology and outcome of the vulnerability mapping. The resulting risk maps are presented and assessed in Chapter 5. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 -2Technical note 2 FLOOD HAZARD 2.1 Description of methodology Floods are dominated by two aspects: the presence of (excessive) water and the topographical characteristics of the area. For example, water is collected in low lying areas, flat surfaces close to a river flood easily and rainstorms in urban areas can cause sudden floods (flash flood). It is possible to develop 1 or 2-dimensional hydraulic models for all catchments in Ghana and calculate all kinds of flood scenarios with them, resulting in flood hazard maps. However, this is very costly both in terms of the data collection process as well as in model building work. Moreover, the purpose of a flood hazard map on national level is mainly to get a general idea of which areas are more prone to flooding than others. Taking this into account we propose a much simpler and easier method to present similar characteristic areas: the Hight Above Nearest Drainage(HAND)-methodology. The HAND method describes the relative height of a certain pixel to its drainage network. Other topographical characteristics like slope and drainage area are also taken into account. The method is described by Renno et al. in 2008. Figure 1 shows the application of the HAND methodology. On the left a DEM (grey) with the drainage pattern (blue) is shown; on the right the HAND index for the same section. The cross sections show that the actual height (upper left) is standardized to the height of the drainage cells (upper right). The HAND index can therefore be used to classify the DEM into hazard zones according to the topology. Figure 1: Example of DEM (left) and HAND indexes (right) from Renno et al. (2008) The hazard zones are related to the type of drainage, being large, medium and small. Table 1 shows the hazard description, HAND-index and hazard classification. This classification results from the validation process. If relevant we will optimize the index, based on new validation information. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Table 1: Physical meaning of the hazard levels Type river Indication of upstream area (km2) Hazard description Large 8100 Medium Small HAND-index High medium low The hazard is caused by large river systems (e.g. rainy season in complete catchment, dam spills). Therefore the high risk zone can be very high due to the large amount of water. <= 7 * * 810 Medium size rivers know hazard of two types. (1) local torrential rainfalls and (2) the high risk zone is depending on water levels directly in a stream, where also currents can occur. The medium risk zone describes fiscally the transition zone where runoff processes start dominating the hydraulic processes. <= 5 5 - 10 * 16 Small catchments are mainly prawn to torrential rains as discharges come directly from the surrounding. Drainage systems can rapidly rise, but also the valley sides are at hazard due to runoff processes. <= 3 3 - 10 10-15 * Higher hand values are not used in that specific layer; the information of a lower layer is used instead The HAND method op national level is based on the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM)DEM. The processing of the DEM is done in PCRaster – an environmental modelling software with raster calculations options. However the processing steps can also be undertaken in other raster processing packages with similar functionalities. In order to calculate the HAND-index these steps were undertaken: 1. Derive flow direction raster 2. Classification of stream network according to the upstream area and the height of the stream according to the DEM 3. Definition of upstream areas for each stream pixel with the same height as the downstream stream pixel 4. HAND index is derived by the difference of step 3 and step 2 For each of the three river types shown in Table 1 the HAND index is calculated. The difference between the river types lies in the classification of the stream. Afterwards the HAND indexes are classified into the three hazard zones. The final hazard map is derived by the combination of the three classified hazard maps for the different stream sizes; the order of the layers is large, medium and finally small river systems. To prove that the HAND method is suitable for the purpose of national flood hazard mapping we validated the method on several typical flood areas. Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 present a validation of the floodplains of the White Volta, the maximum water level in lake Volta and an impression of the hazard levels around the Odaw drain (Greater Accra). The validation shows that the hazard levels are strongly depending on the quality of the measured elevation and the raster size. In urban areas the level of detail of the 90m DEM seems to be too coarse, whereas the high hazard inundation areas of lake Volta and the White Volta are well BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 -4Technical note represented. This is acceptable, because the relatively small Odaw drain is visible as a flood hazard on national level, which is the purpose, and will be further corrected on pilot level. Legend high hazard by HAND classification inundation recorded by Landsat (2000-2009) Figure 2: Validation of the HAND-hazard for the White Volta Hazard level Low Medium High Figure 3: Validation of the high hazard zone of take Volta with the 84m elevation contour line BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Hazard level Low Medium High Figure 4: Validation for the Odaw drain 2.2 National flood hazard map current climate 2.2.1 DEM-based hazard mapping The result of the processing of the DEM is a raster with three hazard classifications. The remaining unclassified area is equal to the area where no inundation hazard is occurring. Figure 5 provides an overview of the national hazard map. The map shows clearly the floodplains of the White Volta as high hazard areas. Also the other larger rivers, lakes and downstream of lake Volta the regions are marked as high hazard. Smaller stream have less visible hazard classifications. When looking at a more detailed scale, it becomes visible that the classification is clearly present (also shown in Figure 4). BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 -6Technical note Figure 5: Example of the flood hazard map for the national level including large water bodies BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 2.3 National Flood hazard map in 2050 For this study we use 2 IPCC scenario’s that are most likely for Ghana, namely A1B and A2. Annex 1 provides the background information and the motivation of these two scenario’s. The precipitation change calculated for the climate scenarios cause the flood hazard in Ghana to change as well. The following precipitation parameters were used to determine the change in flood hazard: the number of days with no rain representing the duration of the wet season, decrease or increase of the number of days with high precipitation events (e.g. more than 50mm or 100mm per day), maximum daily rainfall, the relative change in volume of the annual precipitation. We used the change in these parameters to determine the change in flood hazards for small, medium and large scale catchments. The changes are determined for the six climate zones by using the synoptic meteorological stations within the zones. The climate zones and meteorological stations are presented in Figure 6. For instance, there is one meteorological station, Navrongo, in the Savanna climate zone. For this zone the change in annual precipitation volume for the A1B and A2 climate scenario’s is small. The hazard on large floods will not change for both scenarios. The maximum daily rainfall intensity for the A2 scenario will increase significantly, whereas the intensity for the A1B scenario will decrease. For the A2 scenario it is also likely that heavy rainstorms that cause small scale floods (flash floods) will occur more often and more severe. Therefore there is an increase in the hazard, which reflects in an increase of the HAND index for this class. For the A1B scenario the rainfall intensities decrease and thus a lower HAND index for the small scale flood hazard is likely. Next to that the maximum intensities in the A1B scenario are less than in the current scenario and the number of days with rain will increase. This reflects in a decrease of the average the rainfall intensities throughout the rainy season. The HAND index for flood hazard of medium size catchments will therefor decrease. For the A2 climate scenarios no major changes for the medium size catchments are expected. Thus there is no change in HAND indexes. Table 10 summarizes the changes for all climate zones for the flood hazard for the A1B and A2 IPCC climate scenario relative to the current HAND hazard index. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 -8Technical note Figure 6: Climate zones and meteorological stations BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Table 2: Changes in precipitation patterns in the six climate regions of Ghana for the current, A1B and A2 IPCC climate scenarios. Sketch of yearly precipitation pattern Change in HAND indexes wrt current scenario Climate Change Savanna Parameter A1B A2 Volume ± Period ± Type of river A1B A2 + + Large 0 -1 Intensity - + Medium -1 0 No.events - ± Small -1 +1 Parameter A1B A2 Volume ± ± Type of river A1B A2 Period + + Large 0 0 Intensity - + Medium -1 +1 No.events - ± Small -1 0 Parameter A1B A2 Volume ± + Type of river A1B A2 Period + + Large 0 0 Intensity - ± Medium 0 +1 No.events - - Small -1 -1 Parameter A1B A2 Volume ± + Type of river A1B A2 Period + + Large 0 +1 Intensity - + Medium -1 +1 + Small +1 +2 Guinea Savanna Transitional zone Moistures semi deciduous forest No.events BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 + - 10 Technical note Sketch of yearly precipitation pattern Coastal zone Tropical rainforest Change in HAND indexes wrt current scenario Climate Change Parameter A1B A2 Volume ± + Period + + Intensity ± + No.events + ± Parameter A1B A2 Volume ± + Period + + Intensity + + No.events + ± Type of river A1B A2 Large 0 0 Medium 0 +1 Small +1 +1 Type of river A1B A2 Large 0 +1 Medium +1 +1 Small +2 +1 An extract of the maps of the climate change flood hazard scenarios for the 2050 A1B and A2 IPCC climate scenarios are shown in Figure 7. The extract clarifies the differences between the two scenarios. The tributaries of the White Volta are represented by medium river type in the Guinea Savanna climate region. They let see a decrease for the A1B scenario (left side) flood hazard and an increase for the A2 scenario (right side) for the flood hazard. The extract of the map let also see that the small rivers have a lower hazard classification for the A1B scenario than for the A2 scenario. The difference is according to the tables presented in Table 10. Figure 7: Flood hazards maps for the A1B and the A2 IPCC climate scenarios BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 2.4 Pilot level map outlook On pilot level the mapping will be carried out with the spatially distributed method. The scale of the maps will be the pilot district themselves. On national level the flood hazard mapping is based on a 90m DEM, which is a rather coarse scale. If at pilot level scale more detailed DEM’s with a higher accuracy are available the mapping will be based on these sources. The pilot level maps will be validated during the field visits. 2.5 Assessment of flood hazard maps In the paragraphs 2.2 and 2.3Error! Reference source not found. the results of the national flood hazard mapping are presented. In the first paragraph the results are presented in a spatially distributed way in the latter paragraph are the results aggregated to district level. There are 216 districts in total (census 2010) in Ghana. About a third of the districts are classified as high flood hazard districts; this means that more than 10% of the district area lies in a high flood hazard zone. Another third of the districts are classified as medium hazard zone, which means that more than 10% of the district area lies in a medium hazard zone. The last third of the districts have a low hazard classification, which means that more than 80 % of the districts area is classified as low or no hazard. The exact numbers of the district statistics are presented in Table 3. Looking at the spatially distributed characteristic it becomes visible that roughly 65 % of the country is classified with no hazard. This indicates that these surfaces are located high above the drainage level and inundations are unlikely – however it does not mean that inundations are impossible. From field visit it was concluded that a number of flooded areas are caused by blocked drainage or culverts, which cannot be taken into account on national level. Roughly 10% of the country are classified as high, medium and low hazard regions. Where the major parts of the hazard zones are located along the White Volta and downstream of the Akasombo Dam. The statistics for the spatially distributed flood hazard map are presented in Table 4. Table 3: Overview of district statistics District classification Number of districts Percentage High hazard 76 35% Medium hazard 69 32% Low hazard 71 33% Table 4: Overview of spatially distributed hazard statistics Spatially distributed map Area [km2] Area High hazard 28,640 12% Medium hazard 30,753 13% Low hazard 24,137 10% 155,413 65% No hazard BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 12 Technical note 3 DROUGHT HAZARD 3.1 Description of methodology In contrast with flooding, drought is a slow process. That is the reason why this aspect is often referred to as ‘the slow killer’. See for example World Meteorological Organization website that explains the WMO and UNCCD work on the foundations to build national drought policies: http://www.wmo.int/pages/mediacentre/news/nationaldroughtpolicies.html Drought is dominantly influenced by meteorological circumstances, especially rainfall and evapotranspiration. Whether areas suffer from drought depends on one hand on the spatial variability of these meteorological variables but also on the physical properties of the land surface. For example areas which have deep phreatic groundwater levels are more vulnerable than areas where groundwater can be accessed by the roots in the unsaturated zone via capillary rise. The same applies to areas where access to surface water bodies for irrigation is available. For the hazard mapping of drought on the national scale it was decided to only take into account the meteorological drought, e.g. the rainfall deficit. This means that other hydrological states like phreatic groundwater level (as described above) are not taken into account. The advantage of this method is that this way the interpretation of the maps is unambiguous. Moreover the effect of climate change (e.g. the primary variables like rainfall and temperature) can be incorporated more easily. The method used is based on the idea that the cumulative rainfall deficit is the most important combined variable (evapotranspiration minus rainfall). As both the absolute value of the cumulative rainfall deficit as well as the duration of certain rainfall deficit is of importance a method is used that takes all of these aspects into account by using a threshold value for the rainfall deficit. Rainfall deficit [mm] Input data is available from global datasets, this way the same data is used nation-wide which makes the results more consistent. On district level however, local data can be incorporated. Figure 8: Examples of cumulative rainfall deficit in the Netherlands. (Red line indicates the driest year measured in history, green line indicates the driest 5% of the years, the blue line indicates the median value of all the years and the black line indicates one example year.) BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 3.2 Application of rainfall deficit-method Rainfall data comes from the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM), which is a joint U.S.Japan satellite mission to monitor tropical and subtropical precipitation. The spatial coverage of TRMM extents from 50 degrees south to 50 degrees north latitude and the data has a spatial resolution of 0.25 degree by 0.25 degree. More specifically daily TRMM data (3B42_v7) is used for the period 1998 to 2012 (14 years). Evapotranspiration data is obtained from the Global Potential Evapotranspiration (Global-PET) climate database. Average monthly and annual PET values at a spatial resolution of 30 arc-seconds (approximately 1 km at tropics) are calculated for the 1950-2000 period using the Hargreaves method with available data on monthly average temperature, available from WorldClim database, and monthly extra-terrestrial radiation, calculated using a methodology presented by Allen et al (1998). For more information about the global aridity and PET database we refer to Trabucco and Zomer (2009). For the national level we scaled the PET data to get the same spatial resolution as the TRMM data, using the average value per grid cell. The monthly data was downscaled to daily data, using a uniform distribution. With this data the yearly cumulative rainfall deficit is calculated based on daily time steps using the open source program language R (cran.r-project.org). Figure 9 shows the spatial distribution of the maximum value of the cumulative rainfall deficit for the years 1998-2011. This figure shows that the years 2002, 2004, 2006 and 2011 have the highest values of maximum rainfall deficit. The figure also shows that there is a high spatial variability within Ghana. If the average over the 14 years is calculated for each grid cell (mean in Figure 9), it shows that mainly the northern part and the southeast part of Ghana show the highest maximum rainfall deficit values. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 14 Technical note Figure 9: Spatial distribution of maximum cumulative rainfall deficit for the years 1998-2011. (Also the mean value over the 14 years is shown.) The value of the maximum rainfall deficit alone is not the ideal drought indicator yet. A better indication can be obtained from the number of days that the rainfall deficit is above a certain value (threshold). To define the value of this threshold the statistics of the 14-years average value of maximum cumulative rainfall deficit within Ghana is calculated (Table 5). Based on these statistics the threshold of 600 mm is chosen, being the spatial average value. Table 5: Statistics of the spatial distribution of mean (14 years) maximum rainfall deficit [mm]. Minimum 240 1st quartile 430 Median 621 Mean 602 3rd quartile 736 Maximum 1006 Figure 10 shows the spatial distribution of the number of days that the cumulative rainfall deficit exceeds the threshold of 600 mm. Again the northern part of Ghana emerges as being an area where the number of dry days is relatively high. Also the southeastern part shows up. Again, the size of the problem differs from year to year. Notable dry years are 1998, 2002, 2006 and 2011. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Figure 10: Spatial distribution of number of dry days (in which the cumulative rainfall deficit exceeds the threshold of 600 mm for the years 1998-2012 as well as the 14-years average value.) 3.3 National drought hazard map current climate Table 6 shows the definition of the drought hazard classification. Based on this classification and map with the 14-years average of the number of days that exceed the threshold of 600 mm, the final drought hazard maps are produced. Figure 11 shows the hazard map on the grid level. Figure 12 shows the drought hazard map projected to the districts within Ghana (216 – census 2010). Table 6: Definition of drought hazard classification number of days based on the 14 years average value of number of days that cumulative rainfall deficits exceeds threshold of 600 mm. NO (0) 0-5 LOW (1) 5-20 BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 MEDIUM (2) 20-70 HIGH (3) >70 - 16 Technical note Figure 11: Drought hazard map of Ghana, based on grid data BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Figure 12: Drought hazard map of Ghana projected on the districts. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 18 Technical note 3.4 National drought hazard map in 2050 For this study we use 2 IPCC scenario’s that are most likely for Ghana, namely A1B and A2. Annex 1 provides the background information and the motivation of these two scenario’s. More information, as well as detailed output maps of the 2 climate scenario’s can be found in the separate report (Obuobie, 2014). For drought both the changes in rainfall as in potential evapotranspiration are of interest as these two variables determine the rainfall deficit. The evaporation was calculated using the Hargreaves method. Although the Penman-Monteith method is often preferred (Allen et al, 1998) to use as daily estimate for ET0 the big advantage of the Hargreaves method is that less variables are needed (only daily minimum and maximum temperature and global position to estimate the incoming global radiation). Kra (2013), from university of Ghana, presents a method for the modified Hargreaves method that produces the essentially the same data as Penman-Monteith. For this study the HG1234 method was chosen. Input of the daily data (rainfall, minimum temperature and maximum temperature) for the current climate and the two IPCC climate scenario’s were used to calculate the yearly rainfall deficit for each synoptic station. Figure 13 shows for all the synoptic stations the maximum yearly cumulative rainfall deficit within the 30-years period of current climate and the 2 IPCC scenario’s in a boxplot. In the boxplots (box-andwhisker plots) the black dot denotes the median, solid boxes range from the lower to the upper quartile, and dashed whiskers show the data range. Data that are further than 1.5 times the interquartile range from the nearest quartile are shown as open bullets. Overall the maximum yearly rainfall deficit increases slightly for most synoptic stations for the two scenario’s. For scenario A1B the variation of maximum yearly cumulative rainfall deficit within the 30-years period increases in comparison to the current climate and scenario A2. As explained in paragraph 3.3 we chose a threshold of 600 mm for the cumulative rainfall deficit and use the number of days above this threshold to indicate the hazard level. Figure 14 shows in a boxplot for each synoptic station the number of days that the cumulative rainfall deficit exceeds the threshold of 600 mm. For stations that do exceed this threshold it can be seen that in general the climate scenario’s show an increase of the number of days above this threshold. And again the variation in scenario A1B is higher in comparison to the current climate and scenario A2. Table 7 shows for each synoptic station the number of days within a year that the rainfall deficit exceeds the threshold of 600 mm, averaged over the 30 years period. As we used 6 climate zones within Ghana, the outcomes of the synoptic stations within one climate zone are averaged. Table 8 shows the same information as Table 7 averaged for the 6 climate zones.Table 9 shows this information as percentages. Figure 15 shows the spatial distribution of the relative increment of number of days with rainfall deficit above the threshold value of 600 mm for respectively scenario A1B and A2. Figure 16 shows the average number of days that the cumulative rainfall deficit exceeds the threshold of 600 mm for the current climate and the 2 climate scenario’s. Based on these results the drought hazard classification was applied (Table 6). The resulting drought hazard maps for the climate scenarios A1B and A2 are given in Figure 17. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Figure 13: Boxplot of maximum rainfall deficit within 30-years period for the 22 synoptic stations, for current climate and the 2 climate scenarios A1B and A2. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 20 Technical note Figure 14: Boxplot of number of days within a year that cumulative rainfall deficit is higher than 600 mm for 30 years period of current climate and A1B and A2 scenario. Table 7: Number of days within a year that rainfall deficit is higher than 600 mm, averaged over a 30-years period. For current climate and A1B and A2 scenario current A1B A2 station 76 104 61 Accra 17 14 13 Saltpond 41 19 37 Ada 53 47 64 Tema 104 143 131 Akatsi 156 190 153 Tamale 127 162 123 Yendi 79 183 85 Bole 149 205 195 Wa 13 22 8 Takoradi 3 35 1 Akim Oda 21 35 6 Koforidua 0 9 0 Abetifi 5 54 26 Kumasi climzone COASTAL SAVANNA COASTAL SAVANNA COASTAL SAVANNA COASTAL SAVANNA COASTAL SAVANNA GUINEA SAVANNA GUINEA SAVANNA GUINEA SAVANNA GUINEA SAVANNA MOIST SEMI DECIDUOUS FOREST MOIST SEMI DECIDUOUS FOREST MOIST SEMI DECIDUOUS FOREST MOIST SEMI DECIDUOUS FOREST MOIST SEMI DECIDUOUS FOREST BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 2 89 24 23 228 22 34 120 67 69 235 52 25 0 55 0 19 127 22 18 267 30 Sefwi Akuse Ho Sunyani Navrongo Kete Krachi 31 Wenchi 0 Axim MOIST SEMI DECIDUOUS FOREST MOIST SEMI DECIDUOUS FOREST MOIST SEMI DECIDUOUS FOREST MOIST SEMI DECIDUOUS FOREST SAVANNA TRANSITIONAL ZONE TRANSITIONAL ZONE TROPICAL RAIN FOREST Table 8: Same as Table 7, stations averaged over climate zone climzone COASTAL SAVANNA GUINEA SAVANNA MOIST SEMI DECIDUOUS FOREST SAVANNA TRANSITIONAL ZONE TROPICAL RAIN FOREST current A1B A2 58 65 61 128 185 139 20 49 25 228 235 267 24 54 31 0 0 0 Table 9: Same as Table 8, with percentage values. climzone COASTAL SAVANNA GUINEA SAVANNA MOIST SEMI DECIDUOUS FOREST SAVANNA TRANSITIONAL ZONE TROPICAL RAIN FOREST BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 current A1B A2 100% 112% 105% 100% 145% 109% 100% 247% 126% 100% 103% 117% 100% 228% 130% 100% 100% 100% - 22 Technical note Figure 15: Relative increment of numbers of days with rainfall deficit above 600 mm based for climate scenario A1B (left) and scenario A2 (right) Figure 16: Average number of days that the rainfall deficit exceeds the threshold of 600 mm for the current climate, scenario A2 and scenario A1B. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Figure 17: Drought hazard maps for the A1B (left) and the A2 (right) IPCC climate scenarios 3.5 Pilot level map outlook For the pilot districts we surge for a more detailed estimation of the drought hazards. Instead of the TRMM resolution, the original resolution of the Pet data will be used. 3.6 Assessment of drought hazard maps As described in the methodology we define drought as a meteorological drought. This means the availability of water, either surface water or ground water, is not taken into account. Also the soil and vegetation index are not taken into account, something that was done by the EPA studie (EPA, 2012). The resulting drought map shows a clear spatial distribution within Ghana. The northern part of Ghana shows high hazard, the eastern and southeastern part show both low and medium hazard. The southwest part of Ghana however shows no hazard for drought. One should notice that gives a general overview for the whole nation of Ghana based on an 14years average. This means that also in areas indicated as no hazard, there is the possibility that within this area one could suffer from drought during single years. The opposite counts for areas with high hazard. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 24 Technical note We made an attempt to verify the drought hazard map with the disaster database. However, we doubt whether this disaster database represents the whole country (concentration in the south) and whether it can be related to our definition of drought disaster. For the future climate both IPCC scenario’s show an increase in rainfall deficit but this is spatially distributed. Both scenario’s show mainly in the mid an mid-south part of Ghana an increase in the number of days that the cumulative rainfall deficit exceeds the threshold of 600 mm. Scenario A1B shows more variation than A2 and shows on average an higher increase. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 4 VULNERABILITY 4.1 Description of methodology The basis for the vulnerability maps is the FAO land use map (gha_gc_adg.shp). Comparing this map with e.g. Google or OpenStreetMap, it appeared that a lot of urban areas were missing. Therefore, we updated the map with residential areas as follows: Data was downloaded as a polygon shapefile from the website www.weogeo.com. The residential areas were selected by querying the map: [Landuse] = "residential" Finally the projection was changed to from Mercator Web to UTM30N. With the function “union” in ARCGIS, we combined these two datasets. In case the FAO land use map did not show an urban area, but the OSM data did, this area was changed to residential. The following two figures show the impact of this step. On the left hand side is the FAO land use map. It is clearly visible that only the larger urban areas are included. The map on the right hand side shows the map including the build up areas from the OpenStreetMap. This clearly reflects the urban areas in the whole of Ghana a lot better. The built up area based on FAO data alone is 733 km2, whereas if we include the OpenStreetMap data it become 3253 km2. Figure 18: Updated land use map with built up areas 4.2 Flood vulnerability – situation 2010 Next, we assessed the vulnerability for different `land use classes´ in case of a flood hazard. We looked at 2 alternative classifications (see table in annex 2 to look at the differences between the two alternatives). Results for both alternatives are shown hereunder, alternative 1 on the left, 2 on the right. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 26 Technical note Figure 19: Flood vulnerability for 2 alternatives The map above is now only taking into account the land use. It is also needed to establish the vulnerability for flooding in relation to the population density, for which we uses the 2010 census. Ghana is completely covered by the 2010 census, and for that purpose divided into 173 districts. The population is provided in rural as well as urban areas for each district. We merged the landuse map we prepared with the map with 173 districts. Then, per district, we allocated the amount of people living in urban areas to the urban areas, and the once living in rural areas to the remaining types (excluding ´water bodies´). This resulted in an average population density for rural and urban areas within a district. We use the following table to define the vulnerability for flooding based on population density alone: Table 10: Proposed classification for vulnerability based on population density Pop density (persons/km2) < 30 30 – 250 250 – 500 > 500 Vulnerability for flooding NO LOW MEDIUM HIGH The results are shown in the following figures. On the left hand side, you see the population density for Ghana. On the right hand the vulnerability based on population density. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Figure 20: Population density and proposed vulnerability To determine the overall flood vulnerability, we need to combine the land use vulnerability map with the population density based vulnerability maps. The values in the resulting map is minimal 0, maximum 6.. Classification is done as follows Table 11: Proposed classification for overall flood vulnerability Sum of vulnerability 0 1,2 3,4 5,6 Overall flood vulnerability No Low Medium High Results are presented in the following two figures. (alternative 1 on the left, 2 on the right.) BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 28 Technical note Figure 21: Overall flood vulnerability for 2 alternatives The following 3 tables present the vulnerable areas (in km2) in case (1) we only look at land use, (2) we only look at population density and (3) in case we look at the overall flood vulnerability. Table 12: Flood vulnerability in km2 per alternative, based on land use Vulnerability No Low Medium High Alternative 1 7844 196438 30370 4212 Alternative 2 168384 35898 30370 4212 Table 13: Flood vulnerability in km2 per alternative, based on population density Vulnerability No (incl 7286 water bodies) Low Medium High 92546 142170 1990 3084 BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Table 14: Overall flood vulnerability in km2 per alternative, combining land use and population density Vulnerability No (incl 7286 water bodies) Low Medium High Alternative 1 7318 200377 28008 3159 Alternative 2 86551 121665 27487 3159 The results show that for alternative 1, the population density has not a significant impact on the overall flood vulnerability (the areas for the vulnerability type are in the same order). In case of alternative 2, the population density has an impact, especially the area of ; low vulnerability increases significantly. 4.3 Drought vulnerability – situation 2010 We assessed what the vulnerability is for different `land use classes´ for the drought hazard as well. Again, we looked at 2 alternatives (see table in annex 2 for the differences between the two alternatives). Results are shown hereunder, alternative 1 on the left, 2 on the right. Figure 22: Drought vulnerability for 2 alternatives BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 30 Technical note Table 15: Drought vulnerability in km2 per alternative No Low Medium High Alternative 1 7553 160002 70351 958 Alternative 2 168384 3254 66268 958 The alternatives differ quite a lot. Overall the vulnerability for alternative 2 is much lower that for 1. 4.4 Vulnerability for future (horizon 2050) Changes in vulnerability between the current situation and 2050 is due to projected changes in land use as well as population growth. In a separate study carried out by WRI (Preparation of vulnerability maps (2050 flood and drought scenarios due to socio-economic development, Oktober 2014), it was concluded that: - Human residential and commercial purposes built up areas are expected to grow with 6.56 % on a yearly basis. (Ghana Statistical Service, 2013. 2010 Population & Housing Census: Summary Report of Final Result) - Agricultural lands increases with a rate of 1.9 % per annum (Ghana Statistical Service, 2013. 2010 Population & Housing Census: Summary Report of Final Result) - Population growth rates are based on the available district growth rates from the 2010 Population Census report. Please note that - for the changes in land use, only national figures are available, while population growth figures are on district level. - No indication or plans are available where and how the land use changes will take place. To incorporate the land use changes we did the following: - For each district we determined what the built up area is in 2050, in case 6.56 % annual growth - For each district we determined what the agricultural area is in 2050, in case of 1.9 % growth - We only assume increase or decrease from existing urban or agricultural lands. - In case the total area in a district appears not to be enough to accommodate these changes, we consider that the urban built up area will take prevalence over the rural areas. The growth of population (as well as built-up area and agriculutural area) is year-on-year. That implies that if for a district with a population of 1000 the population growth is 3 %, the increase in absolute numbers is 30 (between 2010 and 2011) and about 95 (between 2049 and 2050). It also means that the number of inhabitants in 2050 is about 3 times more than it was in 2010. See also the following figure as an example BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Figure 23: Example of population growth The forecast changes in land use maps, results in the following two maps for 2010 and 2050. Figure 24: Land use maps for 2010 and 2050 BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 32 Technical note The impact of the 2050 scenario is considerable, as the following tables underlines Table 16: % Area land use in 2010 and 2050 Built up area Agricultural Other 2010 2050 2 16 28 31 70 52 The built up area will be 8 times higher than in 2010. The increase of agricultural area is rather limited, mainly due to the fact that a lot of districts are not capable of accommodating the forecasted growth of urban area as well as agricultural areas. The population data resulted in the following population density map for 2050. Figure 25: Population density for 2050 In overall numbers, the population increases to 64 million in 2050 (based on the growth rates from the 2010 Population Census report), from 25 million in 2010. The increased population density map, together with the new land use dataset results in an updated vulnerability map for droughts and floods. The vulnerability is updated for scenario 2 only. These are shown in the following two figures. On the left hand side, the vulnerability for flooding in 2050, on the right hand side for drought. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 The drought vulnerability increases significantly, mainly due to the fact that all agricultural land is deemed to be highly vulnerable. Figure 26: Flood and drought vulnerability in 2050 4.5 Vulnerability assessment The following table shows the changes in vulnerability for floods as well as for droughts. Table 17: Changes In vulnerability between 2010 and 2050 No Low Medium High Flood 2010 36 51 12 1 Flood 2050 15 37 30 18 Drought 2010 70 1 28 1 Drought 2050 53 16 0 31 For both events, the vulnerability changes significantly the following 40 years. Where in the current situation about 1 % of the country’s area is highly vulnerable to flood, this changes to almost 20 % in 2050. The driving force behind this is the continuous increase in built up areas, together with the increase of population density. The vulnerability for drought increases mainly due to the increase in land to be used for agricultural purposes. The area not vulnerable at all decreases to about half of the countries size, while almost 1/3 will become highly vulnerable. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 34 Technical note Especially the areas that are currently built up will change significantly. Built up areas along the coast will expand, resulting in built up area along almost the whole coastal stretch. Relative smaller built up areas in 2010 will be almost 10 times bigger and all existing cities will have spread out to accommodate the growing population. Parts that are not built up in 2050 will become agricultural, especially in the southern part of Ghana, all area will be used either to live, or as agriculture. The western part remains relatively empty, this is also due to the fact that current activities are limited as well and the presence of natural parks. Remarks: Note that a high vulnerability does not necessary mean a high risk. The next paragraph will present this in more detail. The best national level land cover map currently available was used. In the near future new and more accurate land cover maps will become available and should be used to update the maps we provided. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 5 RISK 5.1 Description of methodology The risk is assessed by multiplying the vulnerability with the hazard. The value for flood vulnerability is presented in the following table: Table 18: Value for flood vulnerability Vulnerability No Low Medium High Value 0 1 2 3 The hazard map is on a scale of 0 – 6, with 0 no flooding, 6 highly frequent flooding. Accordingly, the minimum value for risk is 0 (either the land use is such, that flooding does not result in any problem or it never floods) , the maximum is 18 (valuable land use, frequently flooded) 5.2 Flood risk We propose to use the following classification to convert the risk value to `high, medium, low`. Table 19: Classification from Risk value to Flood Risk Risk value 0 1–4 5 – 10 > 10 Risk No risk Low risk Medium Risk High Risk The following two maps are the flood risk maps, based on land use alone.. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 36 Technical note Figure 27: Flood risk maps, based on land use alone (alternative 1 on the left, 2 on the right) The following 2 maps are also flood risk maps, based on land use & population density (so including the overall flood vulnerability). BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Figure 28: Flood risk maps, based on land use and population density (alternative 1 on the left, 2 on the right) The following table shows the percentage of the territory of Ghana that falls within a risk value, for land use only, as well as for ´land use and population density`, also for both alternatives. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 38 Technical note Table 20: Overview of % of territory of Ghana with a flood risk value for different alternatives Only land use Risk value alternative 1 (%) alternative 2 (%) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 8 9 10 12 15 18 5.3 68 0 0 9 0 11 9 0 0 1 1 0 0 92 0 0 1 0 2 2 0 0 1 1 0 0 Land use and pop density alternative 1 alternative 2 (%) (%) 67 80 0 0 0 0 9 5 0 0 12 6 9 6 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 Drought risk The risk is assessed by multiplying the vulnerability for drought with the hazard. The hazard value for drought is of a scale of 0 – 3 (0: no hazard, 3: high hazard). The resulting map has values between 0 – 9. Proposed Classification is presented in the following table Table 21: Classification from Risk value to Drought Risk Risk value 0 1-3 4-6 6-9 Risk No Low Medium High The following two maps are the resulting drought risk maps. Alternative 1 on the left hand side, alternative 2 on the right hand side. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Figure 29: Drought risk maps for 2 alternatives (alternative 1 on the left, 2 on the right) The following table shows the percentage of the territory of Ghana that falls within a drought risk value for both alternatives. Table 22: % of territory of Ghana with a drought risk value for 2 alternatives Risk value alternative 1 (%) 0 1 2 3 4 6 9 5.4 alternative 2 (%) 42 9 24 16 3 5 0 90 0 3 1 2 4 0 Future flood risk (horizon 2050) To determine the future flood risk, the following information is required: - Vulnerability for 2050, as described in paragraph 4.4, this is only been done for the land use scenario 2 - Flood hazard for climate scenario A1B, as describe in paragraph 2.3 - Flood hazard for climate scenario A2, as describe in paragraph 2.3 BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 40 Technical note Figure 30: Flood risk maps for 2 climate scenarios for 2050 5.5 Future drought risk (horizon 2050) The future drought risk maps are produced by multiplying the future hazard maps (A1B and A2) with the vulnerability map for future climate. Figure 31: Drought risk map for future climate scenarios A1B (left) and A2 (right).Figure 31 shows the drought risk maps for future climate scenario’s A1B (left) and A2 (right). Both use the alternative 2. In the northern part of Ghana in increase in clearly visible. This is mainly due to future land use change and thus increase of drought vulnerability. In the southern part, downstream of lake Volta the high risk is mainly due to an increase of the drought hazard. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Figure 31: Drought risk map for future climate scenarios A1B (left) and A2 (right). 5.6 Flood Risk assessment The following table shows the result of the flood risk assessment for the whole of Ghana. The area with low risk was 5 % in 2010, and will be similar in 2050 taking land use changes and climate change into account. The medium hazard is about 12 % in the current situation, and increases to almost 20 % in 2050, for both climate scenarios. This means that, without any measures of actions, the areas with medium flood risk increases with 50 %. Looking at the high risk area of Ghana, we can see from the table that it increases from about 1% to 4 – 5 % in 2050. This means that the area with high risk is 4 to 5 times as much as it is now. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 42 Technical note Table 23: Flood risk Risk value 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 8 9 10 12 15 18 5.7 Land use alternative 2 current 80 0 0 5 0 6 6 0 0 1 1 0 0 A1B 72 0 0 4 0 6 7 0 2 4 2 2 2 A2 70 0 0 4 0 6 7 0 2 4 3 2 2 Drought Risk assessment Table 25 shows the result of the drought risk assessment for the whole of Ghana. Overall the drought risk increases in the 2050 scenario’s. The area with no risk decreases from 90% in the current situation (for climate reference the period of 1976-2005 is taken) to 80% in 2050 (for climate the period 2036-2065 is taken). The area with low risk is 3 % in the current situation, and will increase to 10% in 2050 taking both land use changes (vulnerability) and climate change (hazard) into account. The medium hazard is about 5 % in the current situation, and decreases to almost 2 % in 2050. Looking at the high risk area within Ghana we see that for the current situation there is no area indicated as high risk and for the future 2050 scenario’s this area will be 6-7%. Although the figures for both scenario’s look the same, averaged over Ghana, the scenario’s show a clear spatial variation. For the a2 scenario the drought risks arises mainly in the northern part of Ghana whereas in the a1b scenario besides the northern region also the area in the southeast (downstream of lake Volta) crops up. Table 24: Drought risk Risk value 0 1 2 3 4 6 9 current 91 0 3 0 1 4 0 a2 82 2 3 5 0 2 6 a1b 80 2 3 6 0 2 7 BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 44 Technical note 6 LITERATURE Allen R.G., Pereira L.S., Raes D. & Smith M. 1998. Crop evapotranspiration: Guidelines for computing crop requirements. Irrigation and Drainage Paper No. 56, FAO, Rome, Italy. EPA, 2012. Flood and drought risk mapping in Ghana – 5 AAP Pilot districts. Wide-ranging Flood and Drought Risk Mapping in Ghana Starting with the Five African Adaptation Programme (AAP) Pilot Districts (i.e. Aowin Suaman, Keta, West Mamprusi, Sissala East, and Fanteakwa Districts) for Community Flood and Drought Disaster Risk Reduction. Kra, E.Y. 2013. Hargreaves Equation as an All-Season Simulator of Daily FAO-56 Penman-Monteith Eto. Agricultural Science Volume 1, Issue 2 (2013), 43-52, http://todayscience.org/AS/v12/AS.2291-4471.2013.0102005.pdf Obuobie, E. Climate Change Scenarios for Ghana, A Consultancy Study on Climate Change Scenarios for Ghana. October 2014, draft Renno et Al (2008) Trabucco, A., and Zomer, R.J. 2009. Global Aridity Index (Global-Aridity) and Global Potential Evapo-Transpiration (Global-PET) Geospatial Database. CGIAR Consortium for Spatial Information. Published online, available from the CGIAR-CSI GeoPortal at: http://www.csi.cgiar.org. http://www.cgiar-csi.org/data/global-aridity-and-pet-database BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Annex 1: background of climate change BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Introduction Future climate change is highly important to incorporate in the national flood and drought risk mapping. Therefor 2 IPCC scenario’s that are most likely to occur in Ghana are selected. This work was executed by local climate expert dr Emmanuel Obuobie, in close corporation with the team members of Royal HaskoningDHV and HKV. This annex provides the motivation for the selection of the 2 IPCC scenario’s used in our study. Furthermore the main outcomes are presented for the 6 climate regions in Ghana. For a more detailed description about the used datasets, the downscaling method and literature references we refer to the report ‘Climate Change Scenarios for Ghana’ (Obuobie, 2014). This report also shows maps about climate variables throughout the year. Motivation for selection of 2 IPCC scenarios A1B and A2 Two sets of daily climate scenario data downscaled from a General Circulation Model (GCM) and Regional Climate Model (RCM) were derived under this consultancy and used for describing changes in climate (rainfall and evapotranspiration) in the 6 climate regions of Ghana. The scenario data comprised rainfall, minimum and maximum temperatures. The temperature data were used in the Hargreaves method (Allen et al, 1998 and Kra, 2014) to compute the evapotranspiration data described in this study. The scenario data are based on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report Emissions Scenarios (SRES) A1B and A2 (IPCC, 2007). The two scenarios were chosen from 6 IPCC SRE scenarios because of their high potential in relating to the future development of Ghana, compared to the others. The A1B was selected as a likely scenario because it represents “business as usual” and lies between the extremes produced by other scenarios (IPCC, 2007). As such, it is a relatively conservative, but not overly cautious, scenario. Considering that a shift from the current energy mix towards a mix in favour of renewable energy is expensive and Ghana is still struggling to build her economy, it does not appear that the ratio of Ghana’s energy mix will change any significantly in the 21st century. This makes the A1B scenario plausible for Ghana. The A2 scenario, which paints a picture of a very heterogeneous world with emphasis on family values and local tradition, was selected as the other likely scenario of interest because it depicts extensive fossil use and a very slow technological change. This is one of the extreme (high greenhouse gas emission) scenarios that can be expected. Currently, Ghana drills oil and very likely to intensify her use of fossil fuel, which may tend to slow technological changes in the near future. This situation makes the A2 scenario a plausible one for Ghana. Nearly all the GCMs used in the IPCC AR4 are consistent in projecting rise in temperature over West African though the magnitude of change varies among models. The same cannot be said for precipitation. The projections for precipitation show significant uncertainty about the magnitude and direction of change. The uncertainty in the projections can be attributed to uncertainty in both future emissions of greenhouse gases (e.g. carbon dioxide), and in the representation of key processes within models. As a result, estimates of climatic risk are best made through the integrations of models in which the uncertainties are explicitly incorporated by using different models and exploring different emissions scenarios. This is often referred to as multi-model ensemble experiment (Diallo et al., 2012). In this way an “ensemble” of results is produced which can be used to quantify the uncertainty in the climate projections using statistical techniques. However, for this study, climate scenario outputs (temperature and rainfall) from the GCM and RCM that best quantifies the current climate were derived and used for the analysis and mapping of climate change in the 6 climate regions of Ghana. Past studies (EPA-Ghana, 2008; Diallo et al., 2012; McCartney et al., 2012; and Obuobie and Asante-Sasu, 2013) have indicated that the ECHAM5 model (Roeckner et al., 2003) together with older versions of ECHAM is one of the few GCMs that realistically simulate most of the features of the West Africa Monsoon and best quantifies the current climate of the wider West Africa BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 -2- region including Ghana. Therefore, climate change scenario data from ECHAM5 and ECHAM5driven RCM only were considered in this study. Main outcomes – projected on the 6 climate regions of Ghana Changes in the future climate relative to the current were analyzed and mapped on the basis of the 6 climatic zones identified in Ghana, namely, Sudanno savannah, Guinea savannah, Transition zone, Deciduous forest, Coastal savannah, and Rain forest (Figure 1). The 22 synoptic stations were grouped into the 6 climate regions (Table 1) and data for the current and future climates for stations within each climate zone were averaged to obtain climate output for the zone. Basic statistics of mean annual and monthly rainfall and evapotranspiration (calculated from the minimum and maximum temperature data) values were computed for each of the 6 zones for the current climate, A1B-driven future climate and the A2-driven future climate. Changes in the future rainfall and evapotranspiration, relative to the current, were determined using equation (1) below modified from Salack et al. (2011): P future P current 100 …………………………………….(1) RPDccs = P current where RPDccs is the relative change in rainfall (%) or evapotranspiration (%), P future is the mean annual or monthly rainfall or evapotranspiration for the future climate, and Pcurrent is the mean annual or monthly rainfall or evapotranspiration for the current climate. The resulting changes in mean annual and monthly rainfall and evapotranspiration for the 6 climate zones were mapped in ArcView GIS. The maps were prepared for changes in future climate under the A1B and A2 scenarios. Report 1 -3 Figure 1: Map of Ghana showing the 6 climate regions of the country Table 1: Groupings of Synoptic stations by climate regions of Ghana Climate region Synoptic stations Sudanno savannah Navrongo Guinea savannah Bole, Tamale, Yendi, Wa Transition zone Kete Krachi, Wenchi Moist Semi Deciduous forest Abetifi, Akim Oda, Akuse, Ho, Koforifua, Kumasi, Sefwi Bekwai, Sunyani, Takoradi Coastal savannah Accra, Ada, Akatsi, Saltpong, Tema Rain forest Axim Changes in Rainfall Rainfall changes projected by REMO for the A1B scenario and ECHAM5 for the A2 scenario are graphically depicted in figures 2 and 3, respectively, as well as in table 2. Under the A1B BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 -4- scenario, the mean annual rainfall is projected to decrease of about 2% - 6% in the 2050, relative to the current values in the 3 southern climate regions (Rain forest, coastal savannah and moist semi deciduous forest) and increase of about 1% to 8% in the 3 northern climate regions (Transition, Guinea savannah and Sudanno savannah) (Figure 2). The projected changes in mean annual rainfall in the 6 climate regions for the 2050 under the A2 scenario are increases of about 3% to 17%, over the current values (Figure 3). The highest increase is expected to occur in the Guinea savannah climate region (16.8%), while the Sudanno savannah climate region is expected to experience the least increase (3.1%) in the annual rainfall. These results are consistent with analysis of climate change for the larger West Africa region (Sylla et al., 2012; Paeth, et al., 2011). Seasonally, the rainfall projections for the 2050 tend towards increases (range of about 3% 47%) in mean values in December - February (DJF), and decreases (about 7% - 23%) in March - May (MAM) for all 6 climate regions under the A1B scenario. The mean seasonal rainfall values in June – August (JJA) show increases (1% - 22%) in four climate regions (Sudanno savannah, Guinea savannah, Transition zone and Moist semi deciduous forest), a decrease of about 6% in the Coastal savannah climate region, and no significant change in the Rain forest climate region. For the same A1B scenario, the rainfall values in September – November (SON) depicts increases of about 4% - 23%, over the current values, for the three northern climate regions (Sudanno savannah, Guinea savannah, Transition zone), and decreases of about 2% 11% in the 3 southern climate regions (Rain forest, Coastal savannah and Moist semi deciduous forest. For the figures we refer to Obuobie (2014). Analysis of the A2 scenario projections for the 2050 reveals positive changes of about 16% 42% in the DJF mean rainfall, relative to the current values, in 4 climate regions (Sudanno savannah, Guinea savannah, Transition zone, and Moist semi deciduous), a slight decrease of about 1% for the Coastal savannah region and no significant change for the Rain forest climate region. The JJA seasonal mean rainfall projections show increases for all the 6 climate regions, with a range of about 5% - 35%. The SON rainfall also shows increases (about 12% - 49%) for the entire climate regions except for the Rain forest where the projection shows a decrease of about 9% in the mean seasonal rainfall. For the MAM season, the 2050 rainfall is expected to decrease in the range of 3% - 6% in for the Sudanno savannah, Transition zone, Coastal savannah, and Tropical Rain forest climate regions, increase by about 22% in the Guinea savannah, and remain significantly unchanged in the Moist semi deciduous climate region. For the figures we refer to Obuobie (2014). Figures 4 and 5 show the current and projected (the 2050) rainfall at the monthly time step for the entire climate regions for the A1B and A2 scenarios, respectively. The mono-modal rainfall pattern observed in the current climate in the Sudanno savannah and Guinea savannah climate regions and the bi-modal pattern in the moist semi-deciduous, coastal savannah, and tropical rain forest are very well preserved in the 2050 climate. In the Transitional zone, the bi-modal pattern observed in the current climate is preserved but weakly in the 2050 climate, with the first peak occurring in March as opposed to June in the current climate. Unlike the A1B scenario, the rainfall patterns and peak months in all the climate regions are likely to remain unchanged in the 2050 under the A2 scenario. Report 1 -5 Figure 2: Changes in annual rainfall in climate regions of Ghana under IPCC A1B scenario BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 -6- Figure 3: Changes in annual rainfall in climate regions of Ghana under IPCC A2 scenario Table 2: Summary of annual rainfall data and projected changes Climate region Current Climate A1B Scenario A2 Scenario (1976-2005) (2036-2065) (2036-2065) Mean rainfall (mm) Projected Mean rainfall (mm) Projected changes (%) Projected Mean rainfall (mm) Projected changes (%) Sudanno savannah 882.2 956.2 +8.4 909.8 +3.1 Guinea savannah 1016.7 1068.4 +5.1 1188.0 +16.8 Transition zone 1234.4 1245.7 +0.9 1388.0 +12.4 Moist semi deciduous forest 1228.0 1166.6 -5.0 1327.8 +8.1 Coastal savannah 763.2 717.1 -6.0 805.3 +5.5 Rain forest 1937.9 1891.7 -2.4 2068.3 +6.7 Report 1 -7 600 Monthly total rainfall (mm) A1B scenario 500 400 300 200 100 0 Jan Feb Mar SS (1976-2005) TZ (1976-2005) CS (1976-2005) Apr May Jun Jul SS (2036-2065) TZ (2036-2065) CS (2036-2065) Aug Sep Oct GS (1976-2005) MSD (1976-2005) TRF (1976-2005) Nov Dec GS (2036-2065) MSD (2036-2065) TRF (2036-2065) Figure 4: Current (1976-2005) and Future (3036-2065) mean monthly rainfall for the 6 climate regions of Ghana (Sudanno Savannah - SS, Guinea Savannah - GS, Transition Zone - TZ, Moist Semi Deciduous – MSD, Coastal Savannah - CS, and Tropical Rain Forest – TRF) under the IPCC A1B scenario Monthly total rainfall (mm) 600 A2 scenario 500 400 300 200 100 0 Jan Feb Mar SS (1976-2005) TZ (1976-2005) CS (1976-2005) Apr May Jun SS (2036-2065) TZ (2036-2065) CS (2036-2065) Jul Aug Sep Oct GS (1976-2005) MSD (1976-2005) TRF (1976-2005) Nov Dec GS (2036-2065) MSD (2036-2065) TRF (2036-2065) Figure 5: Current (1976-2005) and Future (3036-2065) mean monthly rainfall for the 6 climate regions of Ghana (Sudanno Savannah - SS, Guinea Savannah - GS, Transition Zone - TZ, Moist Semi Deciduous – MSD, Coastal Savannah - CS, and Tropical Rain Forest – TRF) under the IPCC A2 scenario Changes in reference evapotranspiration BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 -8- Figures 6 and 7 depict projected changes in evapotranspiration (ETo) in the 6 climate regions of Ghana for the 2050 for the A1B and A2 scenarios, respectively. Under the A1B scenario, the ETo is projected to increase by about 1% - 9% in 4 of the climate zones (Sudanno Savannah, Transition Zone, Moist Semi Deciduous, and Coastal Savannah), decrease by about 12% in the Tropical Rain Forest, and remain significantly unchanged in the Guinea Savannah region. Under the A2 scenario, the ETo is projected to increase by about 5% - 6% across all the climate regions. Figure 6: Changes in annual ETo in climate regions of Ghana under IPCC A1B scenario Report 1 -9 Figure 7: Changes in annual ETo in climate regions of Ghana under IPCC A2 scenario Figures 8 and 9 show the mean monthly evapotranspiration (ETo) for the current period and the 2050 in all the 6 climate regions of Ghana under the A1B and A2 Scenarios, respectively. Relative to the current period, the 2050 projected ETo, under the A1B scenario, were higher in all the 6 climate regions for most part of the year (October – June) except for the Tropical rain forest where the projected ETo was at all time of the year lower than the values of the current period. For the A2 scenario, the projected ETo values were higher than the values of the current period at all times of the year in all 6 climate regions. BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 - 10 - 8 A1B scenario Evapotranspiration (mm) 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Jan Feb Mar Apr SS (1976-2005) TZ (1976-2005) CS (1976-2005) May Jun Jul Aug SS (2036-2065) TZ (2036-2065) CS (2036-2065) Sep Oct GS (1976-2005) MSD (1976-2005) TRF 91976-2005) Nov Dec GS 92036-2065) MSD (2036-2065) TRF (2036-2065) Figure 8: Current (1976-2005) and Future (3036-2065) mean monthly evapotranspiration for the 6 climate regions of Ghana (Sudanno Savannah - SS, Guinea Savannah - GS, Transition Zone - TZ, Moist Semi Deciduous – MSD, Coastal Savannah - CS, and Tropical Rain Forest – TRF) under the IPCC A1B scenario Evapotranspiration (mm) 8 A2 scenario 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Jan Feb Mar SS (1976-2005) TZ (1976-2005) CS (1976-2005) Apr May Jun SS (2036-2065) TZ (2036-2065) CS 92036-2065) Jul Aug Sep GS (1976-2005) MSD (1976-2005) TRF (1976-2005) Oct Nov Dec GS (2036-2065) MSD (2036-2065) TRF (2036-2065) Figure 9: Current (1976-2005) and Future (3036-2065) mean monthly evapotranspiration for the 6 climate regions of Ghana (Sudanno Savannah - SS, Guinea Savannah - GS, Transition Zone - TZ, Moist Semi Deciduous – MSD, Coastal Savannah - CS, and Tropical Rain Forest – TRF) under the IPCC A2 scenario Report 1 -1 Annex 2: Alternatives for vulnerability classification for land use Label Rainfed croplands Mosaic cropland (50-70%) / vegetation (grassland/shrubland/forest) (20-50%) Mosaic vegetation (grassland/shrubland/forest) (50-70%) / cropland (20-50%) Mosaic forest (50-70%) / cropland (20-50%) Closed to open (>15%) broadleaved evergreen or semi-deciduous forest (>5m) Closed (>40%) broadleaved evergreen and/or semi-deciduous forest (>5m) Open (15-40%) broadleaved deciduous forest/woodland (>5m) Mosaic forest or shrubland (50-70%) / grassland (20-50%) Mosaic grassland (50-70%) / forest or shrubland (20-50%) Closed to open (>15%) (broadleaved or needleleaved, evergreen or deciduous) shrubland (<5m) Closed to open (>15%) broadleaved deciduous shrubland (<5m) Closed to open (>15%) herbaceous vegetation (grassland, savannas or lichens/mosses) Closed (>40%) grassland Grassland Sparse (<15%) vegetation Sparse (<15%) grassland Closed to open (>15%) broadleaved forest regularly flooded (semi-permanently or temporarily) - Fresh or BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm Draft Report 30 October 2014 Flood Alternative 1 HIGH MEDIUM MEDIUM LOW LOW LOW LOW LOW LOW LOW LOW LOW LOW LOW LOW LOW NO Alternative 2 HIGH MEDIUM MEDIUM LOW NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO Droughts Alternative 1 HIGH MEDIUM MEDIUM MEDIUM LOW LOW LOW LOW MEDIUM LOW LOW LOW LOW LOW NO NO LOW Alternative 2 HIGH MEDIUM MEDIUM MEDIUM NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO NO brackish water Closed (>40%) broadleaved forest or shrubland permanently flooded - Saline or brackish water Artificial surfaces and associated areas (Urban areas >50%) Bare areas Non-consolidated bare areas (sandy desert) Water bodies Residential NO HIGH NO NO NO HIGH BC5721-101-100/TN1/411750/Nijm 30 October 2014 -2- NO HIGH NO NO NO HIGH LOW LOW NO NO NO LOW NO LOW NO NO NO LOW