Chapter 24 - Measuring the Wealth of Nations

CHAPTER 24

Measuring the Wealth of Nations

Chapter Overview

GDP is a powerful and versatile metric. There are good reasons that it is one of the most

commonly used tools in macroeconomics. It gives a simple measure of the size of an economy

and the average income of its participants. It also allows us to make comparisons over time or

across countries. The system of national income accounts gives us a picture of how output,

expenditure, and income are linked, and a framework for adding up the billions of daily

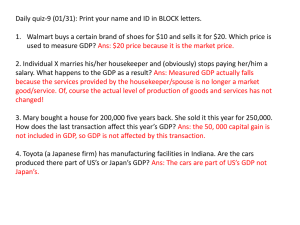

transactions that occur in an economy. Comparing nominal and real GDP allows us to

disentangle the role of increasing prices versus increasing output in a growing economy. The

GDP deflator and the inflation rate track changes in overall price levels over time—which, as

we’ll see in the next chapter, is a major task in macroeconomics. GDP per capita gives us a

sense of the average income within a country, although it doesn’t tell us about the distribution

of income or quality of life. Finally, calculating real GDP growth rates shows us which direction

the economy is moving, and is an important indicator of recession or depression.

In the next chapter, we’ll dig deeper into the tools that economists use to measure price

changes and the cost of living. When we combine these tools with GDP, we have a menu of

macroeconomic metrics that will allow us to describe and analyze national and international

economies.

Learning Objectives

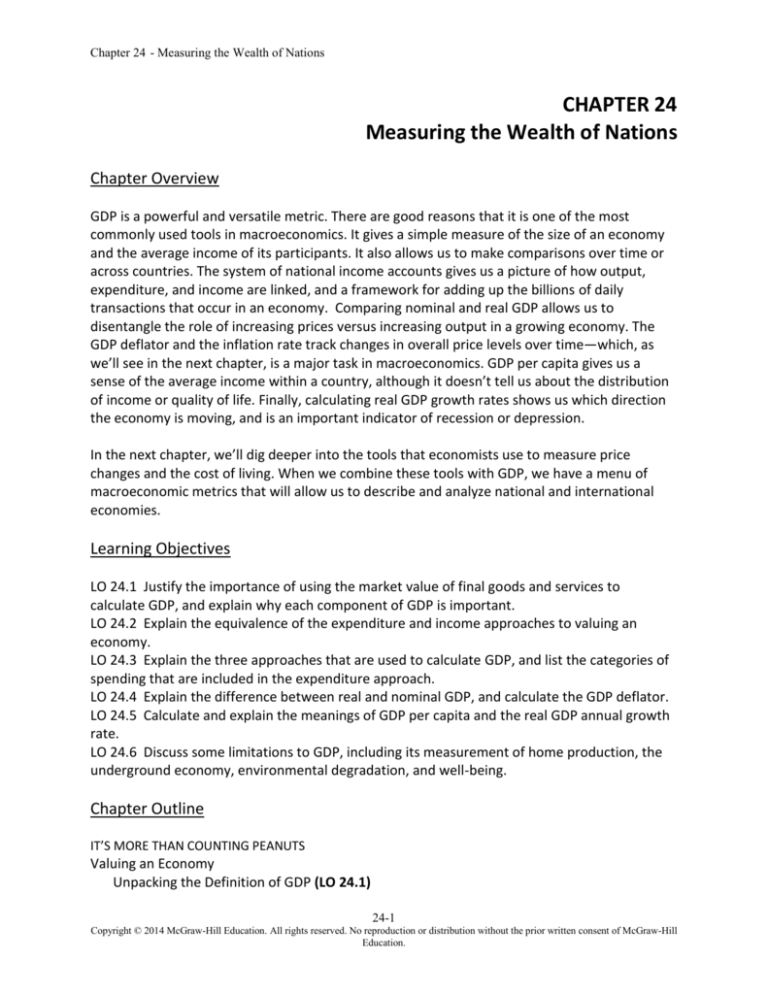

LO 24.1 Justify the importance of using the market value of final goods and services to

calculate GDP, and explain why each component of GDP is important.

LO 24.2 Explain the equivalence of the expenditure and income approaches to valuing an

economy.

LO 24.3 Explain the three approaches that are used to calculate GDP, and list the categories of

spending that are included in the expenditure approach.

LO 24.4 Explain the difference between real and nominal GDP, and calculate the GDP deflator.

LO 24.5 Calculate and explain the meanings of GDP per capita and the real GDP annual growth

rate.

LO 24.6 Discuss some limitations to GDP, including its measurement of home production, the

underground economy, environmental degradation, and well-being.

Chapter Outline

IT’S MORE THAN COUNTING PEANUTS

Valuing an Economy

Unpacking the Definition of GDP (LO 24.1)

24-1

Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education.

Chapter 24 - Measuring the Wealth of Nations

Production Equals Expenditure Equals Income (LO 24.2)

Approaches to Measuring GDP (LO 24.3)

The Expenditure Approach

The Income Approach

The "Value-Added” Approach

Using GDP to Compare Economies

Real versus Nominal GDP (LO 24.4)

The GDP Deflator

Using GDP to Assess Economic Health (LO 24.5)

Limitations of GDP Measures

Data Challenges (LO 24.6)

BOX FEATURE: FROM ANOTHER ANGLE – VALUING HOMEMAKERS

BOX FEATURE: FROM ANOTHER ANGLE – THE POLITICS OF GREEN GDP

GDP vs. Well-Being

BOX FEATURE: REAL LIFE – CAN MONEY BUY YOU HAPPINESS?

Beyond the Lecture

Reading Assignment: Unpacking the Definition of GDP (LO 24.1)

Have students examine the current news release of Gross Domestic Product from the Bureau of

Economic Analysis. This is a great way to introduce students to the calculation of GDP and its

significance.

Writing Assignment: Unpacking the Definition of GDP (LO 24.1)

Have students review the National Income Accounts entry in The Concise Encyclopedia of

Economics. In the article, Mack Ott underscores the importance of GDP for policy purposes.

Then, ask students to write a short essay about the following:

1. Why is GDP and national income accounting important?

2. How is GDP calculated? How is GDP useful for policy decisions?

Team Assignment/Class Discussion: Using GDP to Assess Economic Health (LO 24.5)

Have students use this data on the World Bank site to examine GDP per capita for a specific

country. You may want to assign each student (or group of students) a country to examine. Ask

the students to research their country outside of class before the in-class discussion. In class,

have students discuss the following:

1. What is GDP per capita for your country?

2. How has GDP per capita changed over time for your country?

3. Can you determine why GDP per capita has changed in this fashion?

4. How does GDP per capita for your country compare to other countries?

Class Discussion: Data Challenges (LO 24.6)

Have students view this brief clip from The Colbert Report. In the clip, Colbert discusses

individuals who live off of the garbage of others. Discuss the following:

1. How would the consumption of another person’s garbage impact GDP?

24-2

Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education.

Chapter 24 - Measuring the Wealth of Nations

2. How well does GDP measure well-being? What issues does GDP miss?

Reading/Writing Assignment: Data Challenges (LO 24.6)

Have students read Hiding in the Shadows by Friedrich Schneider, a publication about the

impact of the shadow economy. This is also a great piece for a writing assignment or to

stimulate class discussion.

Solutions to End-of-Chapter Questions and Problems

Review Questions

1. U.S. car dealers sell both used cars and new cars each year. However, only the sales of the

new cars count toward GDP. Why does the sale of used cars not count? [LO 24.1]

Answer: The production of the car was already included in GDP when it was first

manufactured. To include the sale of the used car would serve to double-count the car,

once as a new car, once as a used car.

2. There is an old saying, “You can’t compare apples and oranges.” When economists calculate

GDP, are they able to compare apples and oranges? Explain. [LO 24.1]

Answer: When economists calculate GDP, they are able to make this comparison by

converting production to its dollar value. If the economy produces 10 apples selling at $1.50

each and 5 oranges selling at $1 each, the economy has produced (10 x 1.50) + (5 x 1) = $20

of economic production. The economist has now compared apples and oranges.

3. When Americans buy goods produced in Canada, Canadians earn income from American

expenditures. Does the value of this Canadian output and American expenditure get counted

under the GDP of Canada or the United States? Why? [LO 24.2]

Answer: GDP is the total sum of goods and services produced within a country’s borders.

Goods produced in Canada count in Canada’s GDP even if they are consumed in the U.S.

4. Economists sometimes describe the economy as having a “circular flow.” In the most basic

form of the circular flow model, companies hire workers and pay them wages. Workers then

use these wages to buy goods and services from companies. How does the circular flow model

explain the equivalence of the expenditure and income methods of valuing an economy? [LO

24.2]

Answer: In this basic model all firm revenues are turned into wages, and all wages are spent

on the firms’ products. Thus, total production in the economy can either be measured by

summing up all of the firms’ sales (expenditure method) or all of the workers’ wages

(income method).

24-3

Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education.

Chapter 24 - Measuring the Wealth of Nations

5. In 2011, the average baseball player earned $3 million per year. Suppose that these baseball

players spend all of their income on goods and services each year, and they save nothing. Argue

why the sum of the incomes of all baseball players must equal the sum of expenditures made

by the baseball players. [LO 24.2]

Answer: If nothing from income is left over after spending, then spending must exactly

equal income.

6. Determine whether each of the following counts as consumption, investment, government

purchases, net exports, or none of these, under the expenditure approach to calculating GDP.

Explain your answer. [LO 24.3]

a. The construction of a court house.

b. A taxicab ride.

c. The purchase of a taxicab by a taxicab company.

d. A student buying a textbook.

e. The trading of municipal bonds (a type of financial investment offered by city or state

governments).

f. A company’s purchase of foreign minerals.

Answer:

a. Courthouses are public institutions and are thus counted as part of government

expenditure. In this case, the expenditure is technically an investment by the government.

b. A taxicab ride is a service, so it is counted as consumption.

c. The purchase of a taxicab by the company is an investment.

d. The purchase of a textbook counts as consumption.

e. Neither: Trading financial investments is considered a transfer, which does not go into

the calculation of GDP.

f. The purchase of raw materials from a foreign country is considered an import and is

therefore counted as part of net exports.

7. If car companies produce a lot of cars this year but hold the new models back in

warehouses until they release them in the new-model year, will this year’s GDP be higher,

lower, or the same as it would have been if the cars had been sold right away? Why? Does the

choice to reserve the cars for a year change which category of expenditures they fall under?

[LO 24.3]

Answer: If the cars are produced this year, they count in this year’s GDP even if they aren’t

sold until next year. If the cars are sold right away, they count as consumption (or as

government purchases if they are sold to the government, or as investment if they are sold

to a firm). If the cars are not sold but instead put into inventory, then the production is

counted as investment.

8. The value-added method involves taking the price of intermediate outputs (i.e., outputs

that will in turn be used in the production of another good) and subtracting the cost of

24-4

Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education.

Chapter 24 - Measuring the Wealth of Nations

producing each one. In this way, only the value that is added at each step (the sale value minus

the value that went into producing it) is summed up. Explain why this method gives us the same

result as the standard method of counting only the value of final goods and services. [LO 24.3]

Answer: The only difference between the valued-added method and the final-goods

method is that the production of the economy is added up along the way instead of being

totaled at the end. For example, the height of a staircase is the same whether one measures

each individual stair and adds them up as one climbs the stairs, or whether one simply

climbs all of the way to the top and then measures the total height traveled.

9. Imagine a painter is trying to determine the value she adds when she paints a picture.

Assume that after spending $200 on materials, she sells one copy of her painting for $500. She

then spends $50 to make 10 copies of her painting, each of which sells for $100. What is the

value added of her painting? What if a company then spends $10 per copy to sell 100 more

copies, each for $50? What is the value the painter adds then? If it’s unknown how many copies

the painting will sell in the future, can we today determine the value added? Why or why not?

[LO 24.3]

Answer: The value-added approach determines the value of a good or service by

subtracting the value of the inputs from the value of the outputs. In this case, the painter

originally sold $1,500 worth of paintings, at a cost of $700, which implies that she added

$800 in value by painting. After the company sells another $5,000 worth of paintings at a

cost of $1,000, we can add $4,000 to the original $1,500. If we can’t know how many copies

the painting will sell in the future and at what price, we cannot today know the final value

the painter adds through painting.

10. In a press conference, the president of a small country displays a chart showing that GDP

has risen by 10 percent every year for five years. He argues that this growth shows the

brilliance of his economic policy. However, his chart uses nominal GDP numbers. What might be

wrong with this chart? If you were a reporter at the press conference, what questions could you

ask to get a more accurate picture of the country’s economic growth? [LO 24.4]

Answer: There are many potential problems here. The biggest is that the president is talking

only about nominal GDP and not real GDP. If prices are rising 10 percent per year, then the

country is not experiencing any real growth; GDP is getting bigger only because prices are

rising.

11. Suppose that the GDP deflator grew by 10 percent from last year to this year. That is, the

inflation rate this year was 10 percent. In words, what does this mean happened in the

economy? What does this inflation rate imply about the growth rate in real GDP? [LO 24.4]

Answer: A 10 percent growth rate in the GDP deflator means that, overall, prices in the

economy have risen by 10 percent. This inflation rate implies the growth rate in real GDP is

essentially 10 percent less than the growth rate in nominal GDP.

24-5

Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education.

Chapter 24 - Measuring the Wealth of Nations

12. An inexperienced researcher wants to examine the average standard of living in two

countries. In order to do so, he compares the GDPs in those two countries. What are two

reasons why this comparison does not lead to an accurate measure of the countries’ average

standards of living? [LO 24.4, 24.5]

Answer: Two obvious problems are price levels and population. First, if one country has

higher price levels than the other, then the nominal GDPs of the two countries are not

directly comparable. The country with higher price levels will have a comparably lower real

GDP than a country with low price levels. Second, standard of living is better reflected by

GDP per capita, not simply total GDP. For example, India’s GDP is 15 times larger than

Norway’s, but the average Indian person is quite poor compared with the average

Norwegian since there are 1.2 billion Indians and only about 5 million Norwegians. The

average Norwegian earns almost 15 times that of the average Indian.

13. In 2010, according to the International Monetary Fund, India had the world’s 10th-highest

nominal GDP, the 135th-highest nominal GDP per capita, and the 5th-highest real GDP growth

rate. What does each of these indicators tell us about the Indian economy and how life in India

compares to life in other countries? [LO 24.5]

Answer: With the tenth largest nominal GDP, this statistic tells us that India has a huge

economy that produces lots of goods and services. With the 135 th highest nominal GDP per

capita, this tells us that India is still fairly poor. Its high GDP is a result of being a large

country with a huge population, not the result of being rich. Having the fifth highest GDP

growth rate means that the standard of living in India is rising rapidly and that the country is

becoming more productive.

14. China is a rapidly growing country. It has high levels of bureaucracy and business regulation,

low levels of environmental regulation, and a strong tradition of entrepreneurship. Discuss

several reasons why official GDP estimates in China might miss significant portions of the

country’s economic activity. [LO 24.6]

Answer: In order to avoid the bureaucracy and regulation, small business owners may

operate their firms in the black market. The economic activity created by these small

business owners is real but may be hidden from the view of the government officials

collecting economic data. Similarly, official government GDP statistics are not likely to

include the costs of environmental destruction in their estimates.

15. Suppose a college student is texting while driving and gets into a car accident causing

$2,000 worth of damage to her car. Assuming the student repairs her car, does GDP rise, fall, or

stay constant with this accident? What does your answer suggest about using GDP as a

measure of well-being? [LO 24.6]

24-6

Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education.

Chapter 24 - Measuring the Wealth of Nations

Answer: GDP will rise by $2,000 since car repairs are a service produced by the economy.

Obviously, the economy is not $2,000 better off because of this accident; $2,000 worth of

automobile was destroyed and replaced, but only the replacement, and not the destruction,

was included in the basic measure of GDP. This is an example of where GDP is a distinctly

imperfect measure of well-being.

Problems and Applications

1. Suppose a gold miner finds a gold nugget and sells the nugget to a mining company for

$500. The mining company melts down the gold, purifies it, and sells it to a jewelry maker for

$1,000. The jewelry maker fashions the gold into a necklace which it sells to a department store

for $1,500. Finally, the department store sells the necklace to a customer for $2,000. How much

has GDP increased as a result of these transactions? [LO 24.1, 24.3]

Answer: Only the market value of final goods and services count in GDP, as including the

earlier transactions counts the gold multiple times. Thus, GDP has increased by $2,000, the

price of the final necklace produced. Importantly, GDP has not increased by $500 + $1,000 +

$1,500 + $2,000 = $5,000. Counting the price at each intermediate step serves to double(or triple- or quadruple-) count the production. If one chose to use the value-added method

of GDP, $500 of value is added by the miner; $500 is added by the mining company ($1,000

− $500); $500 is added by the jewelry maker ($1,500 − $1,000); and $500 is added by the

retailer ($2,000 − $1,500). Total value added is $500 + $500 + $500 + $500 = $2,000, the

same as in the final-goods method.

2. Table 24P-1 shows the price of inputs and the price of outputs at each step in the

production process of making a shirt. Assume that each of these steps takes place within the

country. [LO 24.1, 24.3]

a. What is the total contribution of this shirt to GDP, using the standard expenditure method?

b. If we use a value-added method (i.e., summing the value added by producers at each step

of the production process, equal to the price of inputs minus the price of outputs), what is the

contribution of this shirt to GDP?

c. If we mistakenly added the price of both intermediate and final outputs without adjusting

for value added, what would we find that this shirt contributes to GDP? By how much does this

overestimate the true contribution?

Answer:

a. Using the standard expenditure method, the total contribution of this shirt to GDP is

$18.

b. The cotton farmer’s contribution is $1.10 − $0, or $1.10. The fabric maker’s contribution

is $3.50 − $1.10, or $2.40. The sewer and printer’s contribution is $18.00 − $3.50, or $14.50.

Using the value-added method (i.e., summing the value-added by producers at each step of

the production process, equal to the price of inputs minus the price of outputs) the total

contribution of this shirt to GDP is the sum of these three values-added: $1.10 + $2.40 +

$14.50 = $18.00.

24-7

Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education.

Chapter 24 - Measuring the Wealth of Nations

c. If we add the totals at each step we wind up with $1.10 + $3.50 + $18.00, or $22.60 in

total production: an overestimate of $4.60

3. The U.S. government gives income support to many families living in poverty. How does

each of the following aspects of this policy contribute to GDP? [LO 24.2]

a. Does this government’s expenditure on income support count as part of GDP? If so, in

which category of expenditure does it fall?

b. When the families buy groceries with the money they’ve received, does this expenditure

count as part of GDP? If so, in which category does it fall?

c. If the families buy new houses with the money they’ve received, does this count as part of

GDP? If so, in which category does it fall?

Answer:

a. Government income support does not count as part of GDP. Government expenditures

on goods and services count as part of G (government spending), but transfers of income

from one group to another do not count as part of G.

b. When recipients of government transfers spend the money on groceries, this spending

counts as C (consumption). The fact that the spending of the government assistance counts

as part GDP is why the transfer itself doesn’t count as part of GDP. Counting the

government assistance as part of G when it is transferred and then again as C when it is

spent would be double-counting the money.

c. When recipients of government transfers spend the money building new housing, this

spending counts as I (investment).

4. Given the following information about each economy, either calculate the missing variable

or determine that it cannot be calculated. [LO 24.2, 24.3]

a. If C = $20.1 billion, I = $3.5 billion, G = $5.2 billion, and NX = –$1 billion, what is total

income?

b. If total income is $1 trillion, G = $0.3 trillion, and C = $0.5 trillion, what is I?

c. If total expenditure is $675 billion, C = $433 billion, I = 105 billion, and G = $75 billion, what

is NX? How much are exports? How much are imports?

Answer: The expenditure method to calculating the size of an economy involves adding up

all spending on goods and services produced in an economy, and subtracting spending on

imports. The sum of these categories and the equivalence of income (Y) and expenditure

give us the equation Y = C (consumption) + I (investment) + G (government purchases) + NX

(net exports).

a. Total income = C + I + G + NX = $20.1 + $3.5 + $5.2 − $1 = $27.8 billion.

b. Total income = C + I + G + NX. $1t = $0.5t + I + $0.3t + NX. Solving this, I = $0.2 − NX.

Since there are two unknowns (I and NX), neither can be determined.

c. Total income = C + I + G + NX. $675 = $433 + $105 + $75 + NX. Solving for NX, you get NX

= $62 billion. Exports and imports cannot be determined. Since NX is positive, exports are

greater than imports, but we cannot figure out exact amounts with the information given.

24-8

Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education.

Chapter 24 - Measuring the Wealth of Nations

5. Using Table 24P-2, calculate the following. [LO 24.2, 24.3]

a. Total gross domestic product and GDP per person.

b. Consumption, investment, government purchases, and net exports, each as a percentage of

total GDP.

c. Consumption, investment, government purchases, and net exports per person.

Answer:

a. GDP = C + I + G + NX = $770,000 + $165,000 + $220,000 − $55,000 = $1,100,000. GDP per

person = $1,100,000 ÷ 50 = $22,000.

b. C as a % of GDP = $770,000/1,100,000 = 0.7, or 70%. I as a % of GDP =

$165,000/1,100,000 = 0.15, or 15%. G as a % of GDP = $220,000/1,100,000 = 0.2, or 20%.

NX as a % of GDP = −$55,000/1,100,000 = 0.05, or 5%.

c. C/person = $770,000/50 = $15,400. I/person = $165,000/50 = $3,300. G/person =

$220,000/50 = $4,400. NX/person = −$55,000/50 = −$1,100

6. Determine which category each of the following economic activities falls under:

consumption (C), investment (I), government purchases (G), net exports (NX), or not included in

GDP. [LO 24.3]

a. The mayor of Chicago authorizes the construction of a new stadium using public funds.

b. A student pays rent on her apartment.

c. Parents pay college tuition for their son.

d. Someone buys a new Toyota car produced in Japan.

e. Someone buys a used Toyota car.

f. Someone buys a new General Motors car produced in the United States.

g. A family buys a house in a newly constructed housing development.

h. The U.S. Army pays its soldiers.

i. A Brazilian driver buys a Ford car produced in the United States.

j. The Department of Motor Vehicles buys a new machine for printing driver’s licenses.

k. An apple picked in Washington State in October is bought at a grocery store in Mississippi in

December.

l. Hewlett-Packard produces a computer and sends it to a warehouse in another state for sale

next year.

Answer:

a. G. The stadium is a government purchase.

b. C. The student is consuming housing services.

c. C. The parents are purchasing education services.

d. NX. Someone buys a new Toyota car produced in Japan and this increases net exports.

e. Not included in GDP. Only the initial production of a good is included in GDP (in this

case, Japan’s GDP).

f. C. The person is consuming an automobile.

g. I. New home construction is included in GDP as residential investment.

h. G. The government is spending on national defense services.

i. NX rise for the US. In Brazil, NX fall and C rises, leading to no net change in the Brazilian

24-9

Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education.

Chapter 24 - Measuring the Wealth of Nations

GDP.

j. G. The government is spending money on goods and services.

k. C. The apple is produced and consumed in the US increasing C.

l. I. The computer is counted as inventory.

7. Table 24P-3 shows economic activity for a very tiny country. Using the expenditure

approach determine the following. [LO 24.3]

a. Consumption.

b. Investment.

c. Government purchases.

d. Net exports.

e. GDP.

Answer:

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

$707,000.

$600,000.

$800,000.

-$200,000.

$1,907,000.

8. During the recent recession sparked by financial crisis, the U.S. economy suffered

tremendously. Suppose that, due to the recession, the U.S. GDP dropped from $14 trillion to

$12.5 trillion. This decline in GDP was due to a drop in consumption of $1 trillion and a drop in

investment of $500 billion. The U.S. government, under the current president, responded to

this recession by increasing government purchases. [LO 24.3]

a. Suppose that government spending had no impact on consumption, investment, or net

exports. If the current presidential administration wanted to bring GDP back up to $14 trillion,

how much would government spending have to rise?

b. Many economists believe that an increase in government spending doesn’t just directly

increase GDP, but that it also leads to an increase in consumption. If government spending rises

24-10

Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education.

Chapter 24 - Measuring the Wealth of Nations

by $1 trillion, how much would consumption have to rise in order to bring GDP back to $14

trillion?

Answer:

a. To counteract a $1 trillion drop in C and a $0.5 trillion drop in I, you need to raise G by

$1.5 trillion (assuming the increase in G doesn’t affect any other variables in the equation—

expenditures = C + I + G + NX).

b. To counteract a $1 trillion drop in C and a $0.5 trillion drop in I with only $1 trillion in

increased G, C would also have to rise by $0.5 trillion.

9.

a.

b.

c.

d.

Assume Table 24P-4 summarizes the income of Paraguay. [LO 24.3]

Calculate profits.

Calculate the GDP of Paraguay using the income approach.

What would GDP be if you were to use the value-added approach?

What would GDP be if you were to use the expenditure approach?

Answer:

a. Profits = Total business expenditures – Total business revenues = $9 billion.

b. Wages + Interest + Rental income + Profits = $8.3 + $0.7 + $9 = $18 billion.

c. $18 billion: All methods of calculating GDP result in the same value.

d. $18 billion: All methods of calculating GDP result in the same value.

10. Table 24P-5 shows the prices of the inputs and outputs for the production of a road bike.

[LO 24.3]

a. What value is added by the supplier of the raw materials?

b. What value is added by the tire maker?

c. What value is added by the maker of the frame and components?

d. What value is added by the bike mechanic?

e. What value is added by the bike store?

f. What is the total contribution of the bike to GDP?

Answer:

a. $190 = ($20 × 2) + $80 + $70.

b. $20 = ($30 – $20) × 2.

c. $100 = $250 – ($80 + $70).

d. $40 = $350 – [$250 + ($30 × 2)].

e. $150 = $500 – $350.

f. $500 = Sum of value added = Value of final good.

11. Imagine that the U.S. produces only three goods: apples, bananas, and carrots. The

quantities produced and the prices of the three goods are listed in Table 24P-6. [LO 24.4]

a. Calculate the GDP of the United States in this three-goods version of its economy.

24-11

Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education.

Chapter 24 - Measuring the Wealth of Nations

b. Suppose that a drought hits the state of Washington. This drought causes the quantity of

apples produced to fall to 2. Assuming that all prices remain constant, calculate the new U.S.

GDP.

c. Assume, once again, that the quantities produced and the prices of the three goods are as

listed in Table 24P-6. Now, given this situation, carrot sellers decide that the price of carrots is

too low, so they agree to raise the price. What must be the new price of carrots if the U.S. GDP

is $60?

Answer:

a. GDP is the sum of the dollar value of the goods and services produced in a country. In

this case, GDP = $2 × 5 (apples) + $1 × 10 (bananas) + $1.50 × 20 (carrots) = $50.

b. The new GDP = $2 × 2 (apples) + $1 × 10 (bananas) + $1.50 × 20 (carrots) = $44.

c. After carrot sellers raise the price of carrots, the equation becomes $2 × 5 + $1 × 10 + P

× 20 = $60, where P is the price of carrots. We must solve for P, subtracting 20 from both

sides leaving 20(P) = 40. Now divide both sides by 20, leaving P = $2.

12. Based on Table 24P-7, calculate nominal GDP, real GDP, the GDP deflator, and the inflation

rate in each year, and fill in the missing parts of the table. Use 2010 as the base year. [LO 24.4]

Answer:

13. Suppose that the British economy produces two goods: laptops and books. The quantity

produced and the prices of these items for 2010 and 2011 are shown in Table 24P-8. [LO 24.4]

a. Let’s assume that the base year was 2010, so that real GDP in 2010 equals nominal GDP in

2010. If the real GDP in Britain was $15,000 in 2010, what was the price of books?

b. Using your answer from part a, if the growth rate in nominal GDP was 10 percent, how

many books must have been produced in 2011?

c. Using your answers from parts a and b, what is the real GDP in 2011? What was the growth

rate in real GDP between 2010 and 2011?

Answer:

a. GDP is the sum of the dollar value of the goods and services produced in a country. In

2010, $15,000 = 50($200) + 1,000(P) where P is the price of books. Solving for P, we get a

price per book of $5.

b. The first thing we need to do is calculate nominal GDP in 2011 if nominal GDP has grown

10%. GDP(2011) = GDP(2010) x 1.1 = $16,500. Now set $16,500 = 100($150) + Q($10),

24-12

Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education.

Chapter 24 - Measuring the Wealth of Nations

where Q is the quantity of books produced. Solving for Q, we find that 150 books must have

been produced.

c. Using 2010 as the base year, to find real GDP in year 2011, you take the quantities

produced in year 2011 multiplied by the prices in 2010. Real GDP (2011) = 100($200) +

150($5) = $20,750. The change in real GDP = (New GDP − Old GDP)/Old GDP = ($20,750 −

$15,000)/$15,000 = 0.383 = 38.3%.

14. Based on Table 24P-9, calculate nominal GDP per capita in 2008 and 2009, and the real GDP

growth rate between the two years. Which countries look like they experienced recession in

2008–2009? [LO 24.5]

Answer: The United States and Germany. Nominal GDP/capita = Nominal GDP/Population

Real GDP growth rate = (Real GDPnew – Real GDPold)/Real GDPold. A recession is defined as a

period of significant decline in economic activity. Both Germany and the U.S. have negative

real GDP growth year over year, indicating that they are both likely experiencing a

recession. Egypt and Ghana are both experiencing significant growth, so they are clearly not

in recession. Argentina is a borderline case. It is experiencing very slow but positive GDP

growth.

15. Table 24P-10 describes the real GDP and population of a fictional country in 2009 and 2010.

[LO 24.5]

a. What is the real GDP per capita in 2009 and 2010?

b. What is the growth rate in real GDP?

c. What is the growth rate in population?

d. What is the growth rate in real GDP per capita?

Answer:

a. Real GDP per capita equals real GDP divided by population. The only trick here is to get

the right number of zeroes on the billions and millions. The real GDP per capita in 2009 is

$10,000,000,000/1,000,000 = $10,000. The real GDP per capita in 2010 is

$12,000,000,000/1,110,000 = $10,909.

b. Real GDP growth rate = [GDP(2010) - GDP(2009)]/GDP(2009) = (12 - 10)/10 = 0.20 =

20%.

c. Population growth rate = [Pop(2010) - Pop(2009)]/Pop(2010) = (1.1 - 1)/1) = 0.1 = 10%.

d. Real GDP per capita growth rate = [Per capita GDP(2010) - Per capita GDP(2009)]/Per

capita GDP(2009) = ($10,909 – $10,000)/10,000 = 0.0909 = 9.09%

24-13

Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education.

Chapter 24 - Measuring the Wealth of Nations

16. Table 24P-11 shows data on population and expenditures in five countries, as well as the

value of home production, the underground economy, and environmental externalities in each.

[LO 24.5, 24.6]

a. Calculate GDP and GDP per capita in each country.

b. Calculate the size of home production, the underground economy, and environmental

externalities in each country as a percentage of GDP.

c. Calculate total and per capita “GDP-plus” in each country by including the value of home

production, the underground economy, and environmental externalities.

d. Rank countries by total and per capita GDP, and again by total and per capita “GDP-plus.”

Compare the two lists. Are the biggest and the smallest economies the same or different?

Answer:

a. GDP = C + I + G + NX. GDP per capita = GDP/population.

b. The size of home production, the underground economy, and environmental externalities

in each country as a percentage of GDP is the value of each term divided by GDP. The total

can be found by summing up the individual percentages.

c. GDP-plus = GDP + home production + underground economy + environmental

externalities (which are generally negative so this subtracts from GDP). GDP-plus per capita

= GDP-plus/Population.

24-14

Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education.

Chapter 24 - Measuring the Wealth of Nations

e. As can be seen from the table, the parts in GDP-plus that are not counted in GDP can

make a big difference. The biggest change comes in comparing Bohemia and Saxony. Under

GDP per capita Bohemia is about two-thirds richer than Saxony. Under GDP-plus per capita,

Bohemia is more than 2.8 times richer than Saxony.

17. Suppose a parent was earning $20,000 per year working at a local firm. The parent then

decides to quit his job in order to care for his child, who was being watched by a babysitter for

$10,000 per year. Does GDP rise, fall, or stay constant with this action, and how much does GDP

change (if at all)? [LO 24.6]

Answer: GDP falls because the parent is not working in the labor force and is providing a

do-it-yourself service. Previously, GDP generated by the father and the babysitter (by the

income method) would have been $20,000 (from the father’s job) + $10,000 (from the

babysitter’s job) = $30,000. After the change, the GDP generated is $0 since the father

watching his own children is not a market transaction and therefore not counted in GDP.

Thus, GDP falls $30,000. The fact that household work is not counted as part of GDP if

conducted by a member of the family but is counted as part of GDP if a market transaction

takes place is a clear failing of using GDP as a way to measure economic well-being.

24-15

Copyright © 2014 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill

Education.