Lovell-Participatory.. - University of Colorado Boulder

advertisement

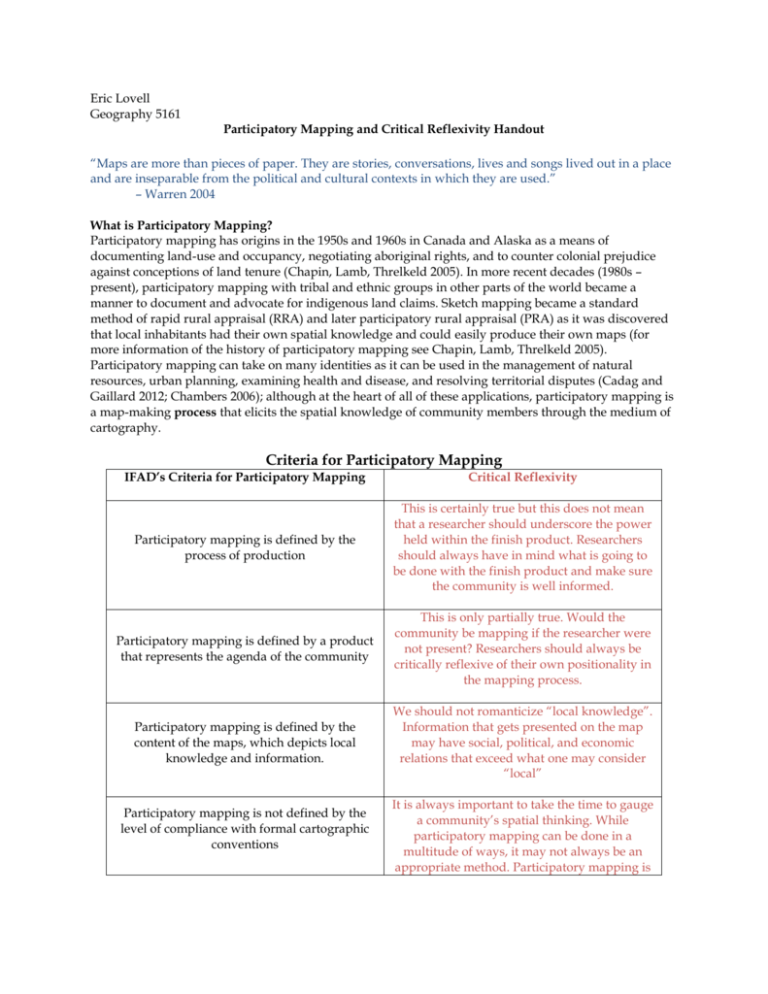

Eric Lovell Geography 5161 Participatory Mapping and Critical Reflexivity Handout “Maps are more than pieces of paper. They are stories, conversations, lives and songs lived out in a place and are inseparable from the political and cultural contexts in which they are used.” – Warren 2004 What is Participatory Mapping? Participatory mapping has origins in the 1950s and 1960s in Canada and Alaska as a means of documenting land-use and occupancy, negotiating aboriginal rights, and to counter colonial prejudice against conceptions of land tenure (Chapin, Lamb, Threlkeld 2005). In more recent decades (1980s – present), participatory mapping with tribal and ethnic groups in other parts of the world became a manner to document and advocate for indigenous land claims. Sketch mapping became a standard method of rapid rural appraisal (RRA) and later participatory rural appraisal (PRA) as it was discovered that local inhabitants had their own spatial knowledge and could easily produce their own maps (for more information of the history of participatory mapping see Chapin, Lamb, Threlkeld 2005). Participatory mapping can take on many identities as it can be used in the management of natural resources, urban planning, examining health and disease, and resolving territorial disputes (Cadag and Gaillard 2012; Chambers 2006); although at the heart of all of these applications, participatory mapping is a map-making process that elicits the spatial knowledge of community members through the medium of cartography. Criteria for Participatory Mapping IFAD’s Criteria for Participatory Mapping Critical Reflexivity Participatory mapping is defined by the process of production This is certainly true but this does not mean that a researcher should underscore the power held within the finish product. Researchers should always have in mind what is going to be done with the finish product and make sure the community is well informed. Participatory mapping is defined by a product that represents the agenda of the community This is only partially true. Would the community be mapping if the researcher were not present? Researchers should always be critically reflexive of their own positionality in the mapping process. Participatory mapping is defined by the content of the maps, which depicts local knowledge and information. We should not romanticize “local knowledge”. Information that gets presented on the map may have social, political, and economic relations that exceed what one may consider “local” Participatory mapping is not defined by the level of compliance with formal cartographic conventions It is always important to take the time to gauge a community’s spatial thinking. While participatory mapping can be done in a multitude of ways, it may not always be an appropriate method. Participatory mapping is not a panacea. Purposes of Participatory Mapping IFAD Purposes of Participatory Mapping To help communities articulate and communicate spatial knowledge to external agencies IFAD Reasoning Critical Reflexivity Mapping can provide a medium to communicate difficult concepts in an accessible manner Researchers must consider that Western Cartesian conventions of cartography may not be accessible to all. This can lead to a misunderstanding of how knowledge is represented in the community. This knowledge may already be catalogued in other, nonspatial forms (songs, dances, etc.) The politics of representing land tenure and desired plans SHOULD NOT be downplayed. Maps can also document access in places where access is contested (i.e., conservation areas) resulting land appropriation, reallocation, and stricter enforcement and management on natural resources. To allow for communities to record and archive local knowledge Can enhance capabilities of poor and indigenous communities and enhance culturally sensitive approaches to development To assist communities in land-use planning and resource management Maps can articulate community desired management plans in regional and government planning. Maps can increase a communities access to productive natural resources and technologies To enable communities to advocate for change Maps can be used to demarcate and demand ownership in areas where customary land has been appropriated by the state. They become a tool for advocacy. Understanding the multiple roles maps can play is critical to understanding their role in empowerment. Claiming advocacy is only part of the picture (See Bryan 2010) Mapping can regenerate a resurgence of interest in local knowledge. This can help a community sustain a sense of place and reinforce a sense of identity Communities are not homogenous. By increasing the capacity of some community members, others may become more marginal. Also, it may not be in the interest of the communities to retain a certain “sense of identity” – communities may want televisions, sneakers, and “Western” clothing. It is important for researchers not to place their own values on other communities. To increase the capacity within communities To address resource-related conflict Maps can delineate boundaries between competing groups over land and resource claims Maps can become agents for conflict making communities more vulnerable to exploitation Types of Participatory Mapping Ground Mapping Uses Strengths Weaknesses Resources Good for beginning to frame spatial issues Useful to engage with non-expert users Product not replicable Raw materials such as soil, pebbles, sticks, and leaves Useful for acquainting individuals to maps and building confidence Low-cost and not technology dependent Impermanent, temporary, fragile, and weather dependent Open space Tangible short-term outcomes Not produced at scale Different types of sand/dirt Most participants can relate to product The medium used may lack credibility as a formal decision-making document Large paper to draw finished product Easily facilitated Cameras to capture finished product Tacitle - can walk around and interact with the map Audio recorder to capture mapping process Easy to alter Can be more democratic and comfortable for individuals Sketch Mapping Uses Strengths Good for stimulating community discussions Useful to engage with non-expert users Good for discussing a broad picture of issues covering large areas Low-cost and not technology dependent Tangible short-term outcomes Weaknesses Outputs are not georeferenced and can only be transposed onto a scale map with difficulty Not useful when locational accuracy is important Lack of accuracy may undermine credibility with government officials Resources Large sheets of paper, pencils, or colored pens Wall or open space to position the map Cameras to record mapping process More detailed and permanent than ground maps May be unfamiliar and inhibiting to individuals Easily facilitated Harder to alter Easily adopted and replicated at community level More exclusive relations may dictate participation and knowledge inclusion Increased legitimacy with officials Vulnerable to removal by outsiders Audio recorder to capture mapping process Scale-Based Mapping Uses Good for communicating information with decision-makers Information on the map can be easily verified on the ground Information can be incorporated into other mapping tools (including GIS) GPS data can be easily transposed onto scale maps Strengths Weaknesses May provide understandable and accurate representation of area Cheaper than producing scale maps with surveyors In many countries, access to accurate scape maps is difficult due to heavy regulation Training required to understand formal cartographic protocols Can be used to determine quantitative information More complex to grasp than sketch and ground maps Pencils and colored pens Solidifies the scale of the mapping conversation GPS Devices Imposes a Western ontology on spatial representation and cognition Will only include formal place-names, which are likely rooted in colonial history Maps may include text in another language and misspellings Resources Scale-based maps Large sheets of Mylar paper to transpose Cameras to record mapping process Audio recorder to capture mapping process May generate insecurity among individuals Participatory 3-Dimensional Mapping Uses Strengths Weaknesses Resources Good to stimulate and inform internal community discussions Finished models can become a community installation Data depicted on model can be extracted, digitized, and plotted Initial creation of the community model is itself a community activity Reusable for multiple planning exercises Access to accurate topographic maps may be difficult Topographic Maps Effective in portraying extensive and remote areas Labor-intensive and relatively time consuming Pushpins, colored string, paint, plaster, and chicken wire Can accommodate overlapping layers of information (like a GIS) Storage of the map can be difficult Pencils and colored pens 3-dimensional aspects may be easily understandable Information must be transferred to another medium Audio recorder to capture mapping process Information on the model can be transposed in a GIS Solidifies the scale of the mapping conversation Camera to document the finished product Imposes a Western ontology on spatial representation and cognition “More indigenous territory has been claimed by maps than by guns. This assertion has its corollary: more indigenous territory can be reclaimed and defended by maps than by guns. Whereas maps like guns must be accurate, they have the additional advantages that they are inexpensive, don't require a permit, can be openly carried and used, internationally neutralize the invader's one-sided legalistic claims, and can be duplicated and transmitted electronically which defies all borders, all pretexts, and all occupations.” – Nietschmann 1995, 37 Structure of the Mapping Process (Some concepts from IFAD 2009) 1) Prepare the community for the mapping process – Prior to the commencement of mapping, it is important to introduce the concept of mapping to the community, the types of tools that will be used and the process of making maps. This should also be a time to highlight the risks involved in mapping and clearly articulate the purpose of the mapping. It is vital here to make sure that it is clear what the limitations of the map are (NO FALSE PROMISES!). This can be done in a community workshop or forum. 2) Determine the purpose of map making – Meeting with community members to determine a strategy about how the map will be created and the issues that will be address is necessary before commencing mapping. This step is a key component to establishing what medium of mapping will be used. It is important to remember that people’s time is precious; therefore, a clear plan should be in place before asking community members to participate. The earlier community members are involved in the process of map making, the more likely they will take ownership of the map. It is also important to careful consider the community politics and power dynamics during this phase. Try to address the most appropriate ways of abiding by the community power relations while also incorporating the voices of all community members. Breaking mapping workshops up into several different workshops may be a helpful way of eliciting different age sets and gender perspectives but always keep in mind the inter and intra-community politics. This will be important 3) Choosing community members to take the lead – This can include training individuals to take an active role in facilitating a mapping process through either language interpretation/articulation, being the primary drawer/sketcher, and collecting information via ground trothing (i.e., collecting GPS points, photographs, etc.). This step entirely depends on the size and type of mapping, which is going to be performed. In many instances, it may not be useful to allocate these tasks to one particular person due to community politics or the fact that all participants are actively interested in physically producing the map (actively drawing instead of just discussing). 4) Creating the map and determining the legend – This is actual participatory process of drawing and creating the map. There are many different directions that can be taken with this process and creativity is critical. Although it is important to have expectations of the direction of participatory mapping, a researcher should always remain flexible as curveballs frequently emerge. 5) Analyzing and evaluating the information – It is important to push to complete mapping projects as maps need to be accurate representations of the views and knowledge of the community. Once a map product is complete, it is important to evaluate the map’s accuracy, completeness, quality, and relevance with community members. This can be done in an iterative process with either individuals or community groups. Individuals should have the right to remove, add, or modify information presented on the map. 6) Using and communicating the community’s spatial information – One of the most significant components of the participatory mapping process is the consideration how might the researcher disseminate the communities mapping products. The community has most likely placed a lot of time and effort into the mapping process. It is critical that this is respected and the completed maps serve the purpose identified in prior steps References and Recommended Reading List: Bryan, Joe. 2010. Force multipliers: Geography, militarism, and the Bowman Expeditions. Political Geography 29, no. 8: 414–416. Bryan, Joe. 2011. Walking the line: Participatory mapping, indigenous rights, and neoliberalism. Geoforum 42, no. 1: 40–50. Cadag, Jake and J.C. Gaillard. 2012. Integrating knowledge and actions in disaster risk reduction: the contribution of participatory mapping. Area 44, no. 1: 100-109. Chambers, Robert. 1994. The origins and practice of participatory rural appraisal. World Development 22, no. 7: 953–969. Chambers, Robert. 2006. Participatory mapping and geographic information systems: Whose map? Who is empowered and who disempowered? Who gains and who loses? Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 25, no. 2: 1-11. Chapin Mac and Bill Threlkeld. 2001. Indigenous landscapes: A study of ethnocartography. Arlington, VA: Cent. Support Native Lands. Chapin, Mac, Zackary Lamb, and Bill Threlkeld. 2005. Mapping indigenous lands. Annual Review in Anthropology 34: 619–638. Craig, William, Trevor Harris, and Daniel Weiner. 2002. Community participation and geographical information systems. New York: CRC Press. De Certeau, Michel. 1988. The writing of history. New York: Columbia University Press Elwood, Sarah. 2006. Critical Issues in participatory GIS: Deconstructions, reconstructions, and new research directions.” Transactions in GIS 10, no. 5: 693–708. Flavelle, Alix. 2002. Mapping Our Land. Alberta: Lone Pine Publishing. Fox, Jefferson, Pralad Yonzon, and Nancy Podger. 1996. Mapping conflicts between biodiversity and human needs in Langtang National Park, Nepal. Conservation Biology 10, no. 2: 562–569. Hodgson, Dorothy, and Richard Schroeder. 2002. Dilemmas of counter‐ mapping community resources in Tanzania. Development and Change 33, no. 1: 79–100. International Fund for Agricultural Development. 2009. Good practices in participatory mapping. Rome: International Fund for Agricultural Development Mbile, Peter, Anne DeGrande, and N Okon. 2003. Integrating participatory resource mapping and geographic information systems in forest conservation and natural resources management in Cameroon: A methodological guide. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 14, no. 2: 1-11. Nietschmann, Bernard. 1995. Defending the Miskito reefs with maps and gps: Mapping with sail, scuba, and satellite. Cultural Survival Quarterly 18, no. 4: 34-38. Pearce, Margaret and Renee Louis. 2008. Mapping indigenous depth of place. American Indian Culture and Research Journal 32, no. 3: 107-126. Peluso, Nancy. 1995. Whose woods Are these? Antipode 27, no. 4: 383-406. Robinson, Catherine and Tabatha Wallington. 2012. Boundary work: Engaging knowledge systems in comanagement of feral animals on indigenous lands. Ecology and Society 17, no. 2: 1-16. Rocheleau, D. (2005). Maps as power tools: locating communities in space or situating people and ecologies in place? In Brosius, J.P, Tsing A.L., Zerner, C. (ed.) Communities and Conservation: Histories and Politics of Community-Based Natural Resource Management, (327-362). Lanham, Maryland: Altamira Press. Rundstrum, Robert. 1991. Mapping, postmodernism, indigenous people and the changing direction of North American cartography.” Cartographica: the International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 28, no. 2: 1–12. Sletto, Bjorn. 2009. ‘We drew what we imagined’. Current Anthropology 50, no. 4: 443–476. St. Martin, Kevin 2005. Mapping economic diversity in the first world: The case of fisheries. Environment and Planning A 37: 959-979. Wainwright, Joel and Joe Bryan. 2009. Cartography, territory, property: Postcolonial reflections on indigenous counter-mapping in Nicaragua and Belize. Cultural Geographies 16, no. 2: 153–178. Warren, Andrew. 2004. International forum on indigenous mapping for indigenous advocacy and empowerment. The Indigenous Communities Mapping Initiative. Personal communication. Cited in: Rambaldi, G. (2005) ‘Who owns the map legend?’, URISA Journal, 17: 5–13. Weiner, Daniel, Timothy A Warner, Trevor M Harris, and Richard M Levin. 1995. Apartheid representations in a digital landscape: GIS, remote sensing and local knowledge in Kiepersol, South Africa.” Cartography and Geographic Information Science 22, no: 1: 30–44.