Introduction To Humanitarian Action for Resident

advertisement

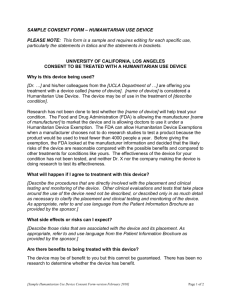

INTRODUCTION TO HUMANITARIAN ACTION FOR RESIDENT COORDINATORS The aim of this paper is to provide Resident Coordinators (RCs) with a snapshot of the key tenets of humanitarian action. A more detailed guide, the IASC Handbook for RC/HCs on Emergency Preparedness and Response, is under revision and will be released at the end of 2015. Hyperlinks are included throughout the document for further reference and reading. RC responsibilities Humanitarian leadership is an integral part of the RC’s role in all countries, whether or not the RC has been designated as Humanitarian Coordinator (HC) and whether or not there is a humanitarian emergency (if not, the RC is responsible for preparing for one). As per the RC Job Description, the RC is responsible for leading and coordinating the emergency preparedness and response activities of UN and non-UN actors, wherever possible in coordination with and support of national authorities. Ultimately, the RC is responsible for ensuring that the international humanitarian response provides affected people with the life-saving assistance they require. If large-scale and/or sustained international humanitarian assistance is required, the Emergency Relief Coordinator (ERC) may decide, following consultation with the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), to designate a HC to lead the humanitarian response in country. If there is a RC in place, the ERC generally designates the RC as HC. In a limited number of cases, based on the context and expertise required, the ERC may choose to designate someone else – a Country Director of an IASC organization or a HC Pool memberi – as HC, or designate a Deputy HC to support the RC/HC. When performing humanitarian functions, the RC works on behalf of the IASC, which includes UN humanitarian agencies, NGOs are the Red Cross/Red Crescent movement; is accountable to the ERC; and is supported by OCHA. Humanitarian context Humanitarian action generally takes place in complex, insecure, and logistically challenging environments. The situation is compounded by intense external scrutiny and constant pressure to provide information and results to headquarters, donors, and the media. Large number of international actors – mostly NGOs and bilateral providers, none of whom have a reporting line to the RC and each with different mandates, accountabilities and cultures – deploy to the country, challenging the RC’s coordination capacity. RCs are expected to take decisions rapidly based on unreliable and fluid information, in fast-paced and often politicized contexts. There is often tension between short- and longer-term response objectives and a shortage of resources, resulting in competition for staff, funds and media attention. Preparedness refers to measures undertaken to be ready and able to respond in the event of an emergency. These measures are broad-ranging and span the humanitarian and development continuum. The IASC guidance on Emergency Response Preparedness spells out what is expected of RCs in this respect. Given the strong inverse correlation between disaster risk and human development, all developing countries face disaster risks and therefore need to be prepared for an emergency. Humanitarian action is based on the premise that human suffering from disaster or conflict should be prevented and alleviated wherever it happens (the “humanitarian imperative”). While each organization may subscribe to a broader set, the four core principles that guide humanitarian action are: Humanity Human suffering must be addressed wherever it is found. The purpose of humanitarian action is to protect life and health and ensure respect for human beings. Neutrality Humanitarian actors must not take sides in hostilities or engage in controversies of a political, racial, religious or ideological nature. Humanitarian action, principles, standards Humanitarian action comprises assistance, protection and advocacy in response to humanitarian needs resulting from complex emergencies and natural disasters, as well as measures to prepare for responding to them. It is provided with the sole purpose of saving lives and reducing suffering in the short-term. Specifically, humanitarian assistance encompasses material aid and the services of trained personnel; protection encompasses activities aimed at obtaining full respect for the rights of individuals, in accordance with international law; and advocacy includes speaking out on humanitarian issues, be it publicly or privately. Draft _ June 2015_HLSU/OCHA Impartiality Independence Humanitarian action must be carried out on the basis of need alone, giving priority to the most urgent cases of distress and making no distinctions on the basis of nationality, race, gender, religious belief, class or political opinions. Humanitarian action must be autonomous from the political, economic, military or other objectives that any actor may hold in relation to areas where humanitarian action is being implemented. For comment The RC has an important role to play in promoting and upholding humanitarian principles in the delivery of aid, and ensuring adherence to them. Role of the State States have primary responsibility to assist and protect all people affected by emergencies within their boundaries. If the affected State is unable or unwilling to provide the required assistance and protection, the RC should strive to ensure that people in need receive the required assistance, while respecting State sovereignty. S/he should do so by advocating with the State to fulfil its obligations and by offering international assistance to support national authorities as appropriate. Increasingly the public and donors are seeking assurances that the resources they provide will be used in the best possible way, both in terms of value for money as well as programmes being developed with and for affected people. A variety of standards and accountability measures have been launched over the years; the three key ones are: ► ► ► In situations where non-State armed groups are in de-facto control of territory, the RC should advocate with these groups and remind them of their obligations under international law. The Code of Conduct for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and NGOs in Disaster Relief is a voluntary code of ten principles to safeguard high standards of behavior among responders. The Sphere Handbook and companion standards are important technical resources for every humanitarian worker in the field, setting common principles and universal minimum standards in humanitarian action. The Core Humanitarian Standard on Quality and Accountability establishes nine commitments that organizations can use to improve the quality and effectiveness of assistance and to facilitate greater accountability to affected communities. A State does not need to formally request international assistance for its people to receive it. While it is preferable that a State declare a state of emergency and/or formally request international assistance, as some international response mechanisms require it to be activated, a State may simply welcome international assistance or at a minimum not oppose it. Agencies already working in country may also re-direct assistance from on-going programmes to the affected people, as appropriate. Relief actors Although these initiatives are not binding on States or the UN, they are useful reference documents. Local communities and affected populations themselves are the first responders in an emergency. They should be fully involved in the relief operation. International law International law serves as a basis for humanitarian action, advocacy and negotiation. It defines the legal responsibilities of States in their conduct with each other and their treatment of individuals within State boundaries, including the fundamental legal standards relating to the protection of individuals and groups and to the nature of assistance that may be provided. Beside national and local authorities – who may themselves be affected by the disaster − a large number of actors deliver assistance in an emergency: community-based organizations, faithbased organizations, national and foreign militaries, national and international NGOs, the national and foreign private sector, the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (IFRC, ICRC, national societies), IOM, UN agencies, neighbouring and other States. Each set of actor has a different mandate and positions itself differently in relation to humanitarian principles and norms. Most actors do not have a permanent presence in the country and deploy only once the emergency strikes. Two main bodies of law apply to humanitarian action. International human rights law still applies in case of natural or man-made disaster, as human rights are inherent to every human being and they are applicable at all times and to all categories of people. International humanitarian law aims to limit the effects of war on people and property and protect vulnerable people. It also establishes measures of protection for humanitarian actors in armed conflicts. NGOs are the main providers of international humanitarian assistance. As such, they are a key constituent of the RC and should be treated as equal partners, on par with UN agencies. They should be involved in strategic decisionmaking and not considered merely as implementing partners. In addition, the key treaties and guidance related to refugees, stateless persons and internally displaced persons are: Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees; Conventions Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons and on the Reduction of Statelessness; Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. In natural disaster settings, the national and international militaries play a particularly important role due to their logistical capacity. They should be used only as a last resort, however. RCs should be familiar with the core concepts of the different bodies of international law to advocate with State and non-State actors on meeting their obligations, and to rely on treaty-based obligations to advocate for humanitarian access and assistance. 2 Draft _ June 2015_HLSU/OCHA For comment International humanitarian architecture Field coordination UN General Assembly Resolution 46/182 (1991) set the framework for the coordination and delivery of international humanitarian aid, while reaffirming the primary responsibility of the State to provide assistance. The resolution created the position of the ERC, the IASC, and the Central Emergency Revolving Fund (CERF). It also defined the role of the RC in coordinating humanitarian aid at the country level; facilitating preparedness; assisting in the transition from relief to development; and supporting the ERC on matters relating to humanitarian assistance. Once a disaster strikes – and preferably before, as part of preparedness efforts − the RC decides, in consultation with national authorities and the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT), on the most appropriate coordination architecture for international responders, taking into account the context, available resources and existing mechanisms. Ideally, the coordination architecture for international responders should build on and complement existing local and national-level mechanisms, instead of creating separate or parallel ones. It is important to keep the coordination structure light and streamlined to allow responders to focus on serving affected people rather than attending meetings. The ERC is appointed by the UN Secretary-General to serve as his principal adviser on humanitarian issues and lead and coordinate humanitarian assistance worldwide. The ERC also holds the function of Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs, i.e. head of OCHA. The three key IASC-agreed coordination mechanisms are: Technical level: Clusters bring together UN and non-UN partners around eleven sectors or technical areas of humanitarian action, with the aim of coordinating their preparedness and response activities. They provide RCs with both a first point of call and a provider of last resort.iii The IASC is the global mechanism for inter-agency coordination on humanitarian assistance, consisting of eighteen UN and non-UN organizations.ii It is composed of three main bodies: the IASC Principals (strategy), the IASC Working Group (policy), and the Emergency Directors Group (operations); these are supported by topic-specific, technical subsidiary bodies. The IASC reviews HC designations and field coordination arrangements, provides hands-on or remote support to HCs and HCTs, and annually reviews the performance of HCs. Clusters are established permanently at the global level and temporarily in countries experiencing a humanitarian crisis if (i) coordination gaps exist or (ii) the national coordination mechanism is unable to meet needs in a manner that respects humanitarian principles. The eleven clusters established by the IASC at global level, along with their Global Cluster Lead Agency(ies), are: The humanitarian aid framework laid out in GA Resolution 46/182 has been refined and expanded over the last twenty-five years through a series of reforms. The two most recent reforms took place in 2005 and 2011. The 2005 Humanitarian Reform introduced a broad range of improvements, including strengthening the HC function; establishing the “cluster approach” to ensure dedicated leadership and capacity for each sector of humanitarian work; and transforming the CERF from a revolving loan to a $450 million grant facility. Cluster Camp Coordination & Camp Management (CCCM) Early Recovery Education Emergency Telecommunications (ETC) Food Security Health Logistics Nutrition In 2011 the IASC agreed to a set of additional improvements, referred to as the Transformative Agenda. These include the creation of procedures for IASC system-wide response to large-scale crises (referred to as Level 3 or L3 emergencies), including the establishment of an Inter-Agency Rapid Response Mechanism to deploy experienced senior humanitarians at the outset of a crisis and empowerment of the HC to make decisions when consensus cannot be reached; application of the humanitarian programme cycle concept; revamped preparedness measures; reinforced commitment to greater accountability to affected people; and other initiatives aimed at simplifying processes and improving inter-agency collaboration. Protection Shelter Water, Sanitation & Hygiene (WASH) Global Cluster Lead Agency IOM/UNHCR UNDP UNICEF/Save the Children WFP WFP/FAO WHO WFP UNICEF UNHCR (overall) UNICEF (child protection) UNFPA, UNICEF (GBV) UN-Habitat (land, housing, property) UNMAS (mine action) IFRCiv (natural disasters) UNHCR (conflict) UNICEF The RC or HC recommends to the ERC and the IASC the establishment of one or more clusters and the designation of a Cluster Lead Agency for each cluster. The Country Director of the Cluster Lead Agency is accountable to the RC or HC for the functioning of the cluster, including appointing a dedicated and skilled Cluster Coordinator. 3 Draft _ June 2015_HLSU/OCHA For comment Operational level: The Inter-Cluster Coordination Group is composed of each cluster’s Coordinator (and Co-Coordinator, if applicable). It focuses on operational collaboration to close delivery gaps, eliminate duplication, and ensure action is taken across clusters to deliver an effective response. The Inter-Cluster Coordination Group feeds operational information from the clusters to the HCT for strategic decision-making and facilitates communication between the HCT and clusters. Strategic level: The HCT is composed of Country Directors of operationally relevant UN and non-UN organizations in country (both national and international). It is responsible for strategic coordination and decision-making of international preparedness and response. It is chaired by the RC or HC. The HCT guides the work of the Inter-Cluster Coordination Group, Clusters and other structures/mechanisms, if established. to RCs and HCs at country level to coordinate preparedness for and delivery of humanitarian assistance, advocate for the rights of people in need, develop humanitarian policies, manage humanitarian information systems, support needsbased planning, and oversee humanitarian pooled funds. OCHA is headquartered in Geneva and New York. Depending on the scale and phase of the emergency, the operational environment and the RC’s requirements, OCHA’s support to RCs may range from remote support from the Regional Office, temporary deployment of staff (surge capacity), placement of a one or more person Humanitarian Advisor Team (HAT) within the RC’s Office, to the establishment of a full-fledged Country Office. The entry point for OCHA support to RCs and HCs is the Country Office and, in its absence, the Regional Office. The focal point for headquarters support is the Director of OCHA’s Coordination and Response Division, who manages field operations. Other bodies may be established to support the management of country-based pooled funds; information management; humanitarian access; humanitarian civil-military coordination; and so forth. OCHA i The IASC HC Pool is a roster of pre-screened candidates for humanitarian leadership positions. It is managed by OCHA. ii Members or standing invitees include UNDP, UNICEF, UNHCR, WFP, FAO, WHO, UN-HABITAT, OCHA, IOM, ICRC, IFRC, OHCHR, UNFPA, the Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of IDPs, the World Bank, and the three NGO consortia - ICVA, InterAction and SCHR. In practice, no distinction is made between members and standing invitees. iii The IASC defines “provider of last resort” as a commitment of the cluster lead agency to call on all relevant humanitarian partners to address critical gaps in the response and if this fails, to commit itself to fill the gap identified by the cluster and included in the humanitarian response plan (or advocate for resources or access to do so). iv IFRC is a ‘convener’ rather than ‘cluster lead’ as it cannot accept accountability beyond those defined in its constitutions and policies. It therefore cannot commit to being ‘provider of last resort’, or hold itself accountable to the UN system, including the ERC and RC/HC. OCHA is an department of the UN Secretariat that provides support to the ERC at the global level and 4 Draft _ June 2015_HLSU/OCHA For comment