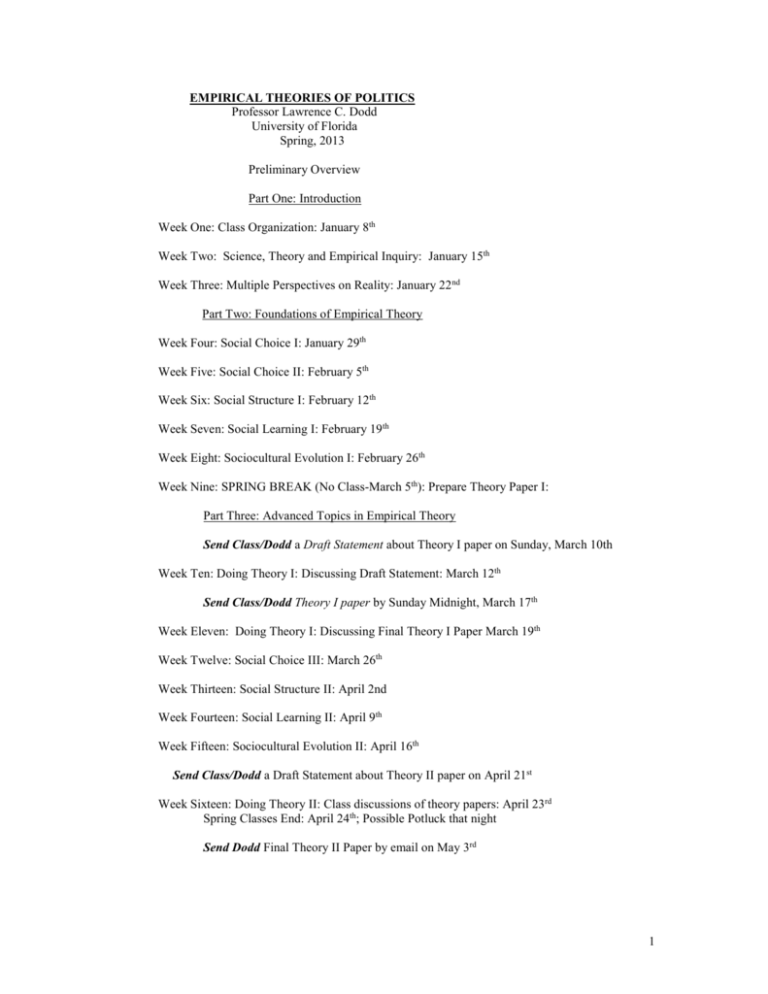

empirical theories of politics - Department of Political Science

advertisement