interpreting prospero – an enigmatic creation

advertisement

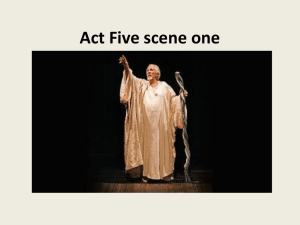

interpreting prospero – an enigmatic creation From colonialist bully to loving father and from allegorical figure to natural leader, Prospero has attracted a wealth of different interpretations. Angus Ledingham suggests that in trying to ‘decode’ his character, we may be missing the point. The character of Prospero in The Tempest is one which lends itself well to different critical readings. His status as a colonist on the island has made the play an object of great interest to postcolonial critics, while his apparent resemblance to Shakespeare’s other ‘wronged princes’ – the Duke in As You Like It being a notable example – can be used to justify a view of the play as an apology for ‘legitimate’ princely power. In fact, regarding Prospero simply as a warning against imperial aggression or as an apology for tyranny falls wide of the mark; Prospero is a fundamentally enigmatic creation whose ‘true’ self is largely concealed, meaning that any attempt to pin down the character, politically or otherwise, will have inevitable limitations. The imperialism of language This is not to say that such approaches lack value; for example, the argument that the relationship between Prospero and Caliban can be interpreted as a representation of imperialism can be justified by reference to the text. The way in which Prospero uses the ‘gift’ of language to dominate Caliban is analogous to ‘cultural’ imperialism, the suggestion being that, by using Prospero’s language, Caliban is remoulded in the image of his master. Just as Stephano comically imitates the behaviour of his social superiors, telling Trinculo ‘I thank thee for that jest, here’s a garment for’t’ in a satirical echo of courtly patronage, Caliban’s violent language – ‘thou may’st knock a nail into his head’ – can be interpreted as an imitation of his master’s lurid threats: I’ll rack thee with old cramps, Fill all thy bones with aches, make thee roar That beasts shall tremble at thy din. A flawed reading? However, the colonial analogy is not an entirely appropriate one; as David Lindley points out, Caliban himself is a colonist on an island which originally belonged to Ariel, suggesting that the relationship between magician and monster was not a straightforward commentary on seventeenth-century empire building. The argument that Prospero was intended as an exploitative tyrant over the ‘innocent’ native Caliban is also a flawed one; while Prospero’s treatment of his servant can seem abhorrent to modern audiences, this should not be confused with Shakespeare’s intentions. While Prospero’s lines: But as ‘tis We cannot miss him. He does make our fire, Fetch in our wood, and serves in offices That profit us now have connotations of economic exploitation, particularly the relation of Caliban’s labour to ‘profit,’ Jacobean audiences would not have viewed master-servant relations in the same way. What would have had more of an impact is Prospero’s claim that: I have used thee, Filth as thou art, with humane care, and lodged thee In mine own cell. This benevolent treatment of his servants would have contrasted comically with Prospero’s brief enslavement of Ferdinand, a member of the nobility. The view that Shakespeare presents Prospero as a good master is supported by the contrast between him and Sycorax. Whereas Ariel was willing to endure punishment for refusing to obey Sycorax’s ‘earthly and abhorred commands’, he willingly follows Prospero’s instructions. Natural authority The suggestion that Prospero is in fact a good master could be used to support an alternative, and more traditional, interpretation; that Prospero represents virtuous, natural authority, contrasting with the corruption of the usurping Antonio. Again there is textual support for such an interpretation, particularly the view that the political structure over which Prospero presides is ‘natural’; he says that when he arrived on the island he ‘was landed/To be the lord on’t’. The fact that the society on his island appears to be a model of a seventeenth-century European kingdom, dominated by a patriarchal ruler with absolute power, suggests that Gonzalo’s hope that such a setting could be the cradle of a new political system is misguided; Prospero’s style of rule is one to which subjects are fundamentally suited. This seems consistent with prevailing trends of both Renaissance and scholastic political theory – that human nature necessitated certain forms of government. However, this emphasis on the play’s philosophical context runs the risk of ignoring the play itself. While the play presents no overt challenge to the ‘legitimate’ form of authority represented by Prospero, Shakespeare’s critical presentation of his character can hardly be called a wholehearted endorsement of such authority either. Contemporary anxieties and a veiled critique An example of veiled criticism on Shakespeare’s part can be found in Prospero’s own account of himself: The government I cast upon my brother, And to my state grew stranger, being transported And rapt in secret studies This is a possible allusion to contemporary anxieties about King James I. Prospero’s description of himself as the ‘prime duke’ would not have been well regarded by a Jacobean audience, since it suggests a division of princely power; Antonio recalls James’s ‘overmighty subjects’ – favoured courtiers who were perceived as wielding excessive influence. Prospero’s ‘secret studies’ also suggest an allusion to James as the scholar king, who was seen as preoccupied with learning at the expense of governing (this may explain why, in Gonzalo’s utopia, ‘letters should not be known’). A bad ruler? In the scene involving the attempted murder of Alonso, which parallels Prospero’s usurpation, it is worth noting that the moral case for the removal of bad rulers (an idea which was not heretical in Jacobean England) is made; Antonio claims that Alonso is ‘no better than the earth he lies upon.’ While Shakespeare does not seem to present either usurpation as justified – in Act 3 Scene 3 Ariel describes to Alonso, Sebastian and Antonio the almost universal revulsion at their crimes – the very fact that Antonio makes this argument, rather than simply appealing to Sebastian’s ambition, reinforces the suggestion that bad rulers are a genuine phenomenon and that Prospero could be one of them. While it would be wrong to present The Tempest as a radical republican text, it cannot be denied that its presentation of Prospero’s authority is ambivalent; his implied blackmail of Antonio and Sebastian following his restoration hardly sets the tone for a just polity. While he is no imperialist monster, Prospero is not presented as an unquestionably virtuous ruler either, raising further questions about the nature of the character. A blank slate Considering the difficulties of defining Prospero in political terms, it is perhaps appropriate that it is the exercise of power which distances him from the audience. What is interesting about Prospero’s power on the island is that he faces no real competition. It is in this sense that he is much less a ‘character’ than any of the other protagonists, since he never faces a challenge which could be the source of the kind of dramatic tension which playwrights use to demonstrate character. When he is shown to feel threatened by the (incompetent) rebellion of Caliban and his ‘confederates’, what could have been a moment of self-revelation is taken up by a deeply nihilistic speech in which he claims that: We are such stuff As dreams are made on which suggests a lack of any true self to which the audience can relate. So long as he exercises power, he remains almost a blank slate; even when he tells Miranda about his past, he ensures that he has a firm control over what information she is allowed to have, telling her: Here seek no more questions Thou art inclined to sleep. Not character but narrative The fact is that Prospero is not an ordinary character who is affected by the narrative; he is the narrative. It is quite clear that everything which happens in the play from the tempest itself to the humbling of Alonso, Sebastian and Antonio, happens because he wants it to. At one point he even suggests that he has consciously staged the relationship between Ferdinand and Miranda in the manner of a chivalrous romance, telling his prospective son-in-law All thy vexations Were but my trials of thy love, and thou Hast strangely stood the test. Shakespeare deliberately uses the play’s staging to show how the exercise of this enormous power physically distances him from the other characters: in Act 3 Scene 1 he watches Ferdinand and Miranda from a distance, while in Act 3 Scene 3 he appears on the top ‘to direct and observe events’; normal dramatic interaction is impossible for such a character. This is why Prospero’s only true self-revelation is in his soliloquy in the play’s Epilogue, after he has abandoned magic. Having relinquished his power, we see him reduced to the level of an ordinary mortal, forced to plead with his audience as if to a divinity: As you from crimes would pardoned be, Let your indulgence set me free. However, this is but a tantalising glimpse of the man behind the ‘baseless fabric’, who remains an enigma to the end. Resisting simple interpretation The character of Prospero provides a wealth of material for a study of Shakespeare in the context of Jacobean thought and politics. However, any attempt to ‘decode’ the character as a mere political allegory or to treat him as a typical, realistic character risks losing sight of the most important aspect of Shakespeare’s last great creation; that his presentation and unique status in the narrative mean that he remains an enigma throughout. Angus Ledingham is a first year English student at Cambridge University. This article first appeared in emagazine 43, February 2009. top