Hammock Ethan Hammock Professor Marshall Honors English

Hammock 1

Ethan Hammock

Professor Marshall

Honors English Composition

10/20/2014

Crime and Punishment in Georgia

Two distinct issues arise in the debate over the ethics of capital punishment. The first is whether or not any human deserves to die as punishment for a crime he has committed. Anyone who answers “no” to this question will face bombardment from death penalty advocates who ask sardonically why it would not be ethical to execute Adolf Hitler if he were alive today. This is a reasonable argument. The second issue that arises is whether or not we should trust an inherently corrupt legal system to decide which men deserve to die for their crimes and which men do not.

A closer look at the state of Georgia’s death row system warrants that capital punishment in

Georgia should cease.

Georgia inmate Troy Davis sat on death row for twenty years. In 1989 he was arrested for the murder of police officer Mark MacPhail, and in 1991 a jury found him guilty of the crime, sentencing him to death. Surprisingly, the prosecution presented no murder weapon, no DNA evidence, and no other type of physical evidence at all during his trial. The prosecution instead presented nine eyewitness testimonies affirming that Davis shot the officer. By 2011, seven of those witnesses had come forward admitting that police had pressured them to testify that Davis was the shooter. Of the two witnesses who did not come forward to recant their testimony, one was the man who initially named Davis as the shooter in the incident. Coincidently, the witness was also the secondary suspect for the murder (Hammock). On September 21, 2011, Davis was executed despite the controversy surrounding his case. In the state of Georgia’s justice system, a

Hammock 2 disproportionate amount of cases are handled with this same degree of reckless disregard for human life.

Five to ten percent of U.S. death row inmates suffer from mental illness (“Mental

Illness”). The variance in this statistic is reflective of the manner in which our justice system treats the mentally ill. When a defendant in Georgia claims he suffers from a mental illness during a death penalty case, the burden of proof in the case shifts from the prosecution to the defense. To make matters worse, the standards for proving mental illness constantly become increasingly difficult, and proof of mental illness does not eliminate the possibility of a defendant’s execution. A mentally ill defendant may be executed in Georgia if the prosecution can prove that the defendant was aware of his actions during the commission of his crime and adequately comprehends the punishment that awaits him.

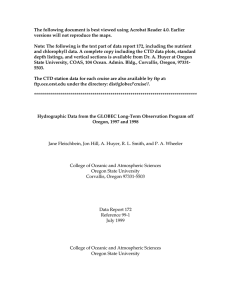

Death row systems are incredibly inefficient. As of January 1, 2014, Georgia had eightyfive death row inmates (“Inmates Under Death Sentence”). As calculated in the table attached, the average amount of time an inmate had spent on Georgia’s death row was roughly sixteen years. Thirty-one percent of the inmates had been on death row for twenty years or more, and seven percent of the inmates had been on death row for over thirty years, with the record reaching thirty-eight years (see Table). The financial expense of putting inmates through appeals during these excessive amounts of time, combined with the cost of execution, far exceeds the cost of life imprisonment (“The High Cost”).

Executions also often go wrong. This has happened too often in Georgia. During the execution of Alpha Otis Stephens in 1984, executioners failed to kill him with their first charge of electricity. After a two-minute charge, he remained alive for six minutes, during which time he was only able to take twenty-three breaths. In 2001, executioners botched the lethal injection

Hammock 3 of Jose High. After failing to find a vein they could use, they stuck needles into his hands and neck. The injection took over an hour to kill him. More recently, in 2010, a similar failure to find a usable vein resulted in the forty-five minute execution of Brandon Joseph Rhode. After the executioners injected him successfully, it took fourteen minutes for the concoction of drugs to kill him. In addition to this, his execution had been delayed for six days after he attempted suicide with a razor blade that a prison guard had given him (Radelet).

A common argument of death-penalty advocates is that execution brings justice to victims’ families. Knowing that a loved one’s murderer no longer lives and has no chance of harming anyone else brings these families closure. By the same reasoning, is it not true that we should bring justice to the families of the innocent men and women who have been wrongly executed? Should we then execute his prosecutors, judges, and executioners?

Another argument of death penalty advocates is that the death penalty can be used to deter crime. They argue that harsher punishments yield more effective deterrence. However, criminological studies have time and time again proven that use of the death penalty deters crime no more than lengthy prison sentences do. Conditions in the South demonstrate this well. The

South has both the highest execution rates and the highest murder rates. Statistics show that over time murder rates have fallen consistently in death penalty states and non-death penalty states alike (“Deterrence”).

The most common argument used in support of the death penalty is simply that there are some criminals out there who have acted so immorally that they deserve death. Regardless of any truth in this statement, it does not follow that we should place the authority to punish by death in the hands of our government. The pervasiveness of human error in our government (and

Hammock 4 especially in our courts) demands that we not give it the authority to make the irreversible decision of punishment by death.

The innocent lives that have been lost in attempts to bring justice through use of the death penalty prove that the death penalty ultimately leads to failure of justice. The state of Georgia has foolishly abandoned this principle, and the current condition of its justice system begs for our attention. As citizens of Georgia, we have the duty to improve our justice system. For some, this means dedicating their careers and even lives to improving it. At the very least, it means facing the harsh reality of its condition and urging others to do the same.

Hammock 5

Works Cited

“Deterrence: death penalty fails to deter crime.” Death Penalty . Web. 19 October 2014.

Hammock, Christen. “No Evidence, No Execution for Troy Davis.” Red and Black . University of Georgia, 18 September 2011. Web. 17 October 2014.

“The High Cost of the Death Penalty.”

Death Penalty . Web. 18 October 2014.

“Mental Illness and the Death Penalty.”

American Civil Liberties Union . 5 May 2009. Web. 17

October 2014.

Radelet, Michael L. “Examples of Post-Furman Botched Executions.” Death Penalty

Information Center . University of Colorado, 24 July 2014. Web. 18 October 2014.

State of Georgia Department of Corrections. “Inmates Under Death Sentence January 1, 2014.”

Department of Corrections . Office of Planning and Analysis, 1 January 2014. Web. 18

October 2014.

Hammock 6

Georgia Death Row Statistics

Last Name

Edenfield

Esposito

Foster

Franks

Fulls

Gary

Heidler

Henry

Hill

Hittson

Holiday

Holsey

Hulett

Humphreys

Jarrells

Jefferson

Arevalo

Arrington

Barrett

Bishop

Branan

Brockman

Brookins

Butts

Clark

Cohen

Collins

Conner

Cromartie

Drane

Drucker

Johnson

Jones

Jones

Jones

King

Lance

First Name

Joaquin

Robert O.

Winston Clay

Joshua Daniel

Andrew

Ward A.

Brian Duane

Robert

Cleveland

Michael A.

Roger

John W.

Ray J.

Leonard

Joshua

David Homer

John

Timothy T.

David Scott

Kenneth E.

Carlton

Jerry

George R.

Warren

Travis Clinton

Dallas B.

Robert Wayne

Donnie Allen

Stacey Ian

Jonathen

Lawrence

Marcus

Ashley Lyndol

Brandon Astor

Jerry William

Warren

Donnie Cleveland

Table

Sentenced

Jul-10

Oct-98

May-87

Feb-98

May-97

Aug-86

Sep-99

Nov-94

Sep-91

Mar-93

Nov-86

Feb-97

Apr-04

Sep-07

Mar-88

Mar-86

Oct-99

Aug-01

Mar-05

Feb-96

Jan-00

Jun-90

Oct-07

Nov-98

Jul-09

Dec-86

Nov-77

Jul-82

Oct-97

Sep-92

Oct-11

Apr-98

Jun-95

Oct-79

May-08

Sep-98

Jun-99

Years on Death Row

22.25

20.75

27.08

16.92

9.67

5.25

25.75

27.75

3.42

15.17

26.58

15.92

16.58

27.33

14.25

19.08

15

4.42

27

36.08

31.42

16.17

21.25

2.17

14.17

12.33

8.75

17.83

13.92

23.5

6.17

15.67

18.5

34.17

5.58

15.25

14.5

Stinski

Tate

Terrell

Tharpe

Tollette

Waldrip

Walker

Walker

Wellons

Whatley

Williams

Willis

Pace

Palmer

Perkins

Perkinson

Presnell

Pye

Raheem

Raulerson

Rice

Riley, Sr.

Rivera

Rogers

Sallie

Sealey

Sears

Spears

Lawler

Ledford

Ledford

Lee

Lewis

Lucas

Maldonado

Martin

Meders

Miller

Mitchell

Moody

Morrow

Nance

O'Kelly

Mar-96

Nov-97

Jun-97

Sep-99

May-76

Jun-96

Feb-01

Mar-96

Jul-08

Mar-03

Feb-04

May-82

Mar-91

Aug-02

Sep-93

Mar-07

Mar-00

Nov-92

May-09

Jun-97

Nov-98

Sep-99

Sep-12

Jan-05

Apr-89

Nov-88

Jan-90

Apr-07

Jun-99

Sep-97

Nov-05

Jun-07

Dec-05

Jan-95

Jan-91

Nov-97

Oct-94

Oct-02

Jan-05

Jun-93

Jan-97

Apr-04

Jun-10

Gregory

J.W.

Michael

James Allyson

Christopher K

Daniel

Pablo

Dekelvin

Jimmy Fletcher

Michael

Nelson Earl

Jeremy

Scotty

Michael Wayne

Dorian F.

Lyndon Fitzgerald

Willie

David Aaron

Eric

Virgil D., Jr.

Willie James

Mustafa A.

Billy Daniel

Lawrence

William David

Reinaldo Javier

James R.

William

Richard

DeMarcus Ali

Steven Frederick

Darryl Scott

Nicholas

Bryan Keith

Keith Leroy

Leon

Tommy Lee

Artemus Rick

Gregory

Marcus A.

Frederick R.

Joseph

Demetrius Gosheun

5.5

10.75

9.92

31.58

22.75

11.33

20.25

6.75

17.75

16.08

16.5

14.25

37.58

17.5

12.92

17.75

9

24.67

25.08

24

6.67

14.5

16.25

8.08

13.75

21.08

4.58

16.5

15.08

14.25

1.25

6.5

8

18

23

18.08

19.17

11.17

9

10.5

17

9.67

3.5

Hammock 7

Wilson

Wilson

Worsley

Young

Gissendaner

Marion, Jr.

Willie J., Jr.

Johnnie A.

Rodney

Kelly Renee

Nov-97

Feb-82

Nov-98

Mar-12

Nov-98

16.06

31.92

15.08

1.75

15.08

Average: 16.1 years

% over 20 yrs: 31

% over 30 yrs: 7

Hammock 8