DeJongeMAThesisMcMaster - MacSphere

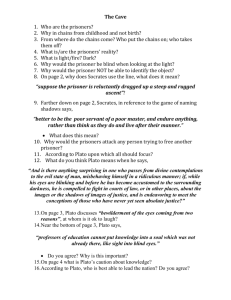

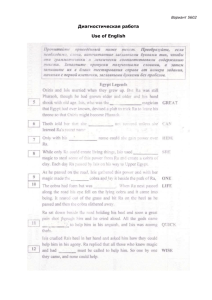

advertisement