Academic English

advertisement

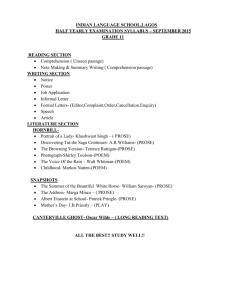

Visser ’t Hooft Lyceum Leiden English Department ACADEMIC ENGLISH 1. Problems of definition Academic English is the kind of written prose associated with academic research or papers (not concerned administrative prose or oral presentations). It can be in any field of academic activity, although there are major differences between the humanities and the ‘hard sciences’. The institutional framework for academic English is determined by: 1) the fact that English is the prime language for publication of academic work in all countries, especially in the hard sciences, to the point where the majority of its writers and readers are non-native speakers, 2) the prestige of a particular text is largely marked by the journal in which it is published in the case of articles or the publisher in the case of books. The kind of English used tends to depend on their preferences or requirements and not on the writer. This situation means that academic English is often highly technical, for communication between experts whose L1 is not English. It can be very dense with respect to terminology. However the syntax of academic English, at least in the sciences, shows a tendency to simplification, with preferences for short sentences, a reduced set of logical connections, and virtually no ‘ornamentation’. The history books trace the development of this kind of English to the 18th century, when scientific empiricism extended the lexis of English enormously. This extension was, however, associated with Puritan aesthetics, which in themselves emphasised plainness and democratic accessibility. English prose was thus ideally as simple as possible. Puritans’ prose, like their churches, had simple wood squares and a bare cross. One could go further. English prose of the 18th and 19th centuries assumed a world of transitivity (things changing other things), encapsulated in the central Subject-Verb-Object, which remains the basic structure for English prose. This was a world of change through power. That world was also profoundly rationalist, in the Newtonian sense that Nature was thought to work according to fixed relationships which the scientist had only to discover. A description of the world thus required very few subjective markers - everyone who looked closely enough or objectively enough—this was the age of advanced in optics—would see the same relationships. Descriptions also required few adverbials, since the logic of the relationships was in the world and not in the manner of their description. If you select the items in the right way, and present them in the right order, their natural relationships will be immediately obvious to the reader. There is thus no real need for ‘and then’, ‘on the other hand’, ‘also’, ‘we can say that’, ‘looking at X, and from the perspective of Y...’. All of that adverbial architecture is traditionally kept to a minimum. We might thus explain the relative plainness of academic prose in terms of both this historical background and the fact that it is now used as a means of communication between non-native speakers. Yet these two factors are interrelated: the Puritans had their strongest influence in the United States; it was in 19th century America that waves of immigration required a 1 Robert Laytham Visser ’t Hooft Lyceum Leiden English Department reformed English for use by non-natives; and it is now American English that tends to dominate the most prestigious scientific journals. 2. Variation and style Variation means people having different names; words have different pronunciations. It should be clear that it operates beyond the sphere of right versus wrong: it is a question of convention, not of norms, there is no specific penalty for non-compliance. Sociolinguists talk about speech ‘styles’ as sets of concurring variants (formal. casual, etc.). In the case of academic English, however, certain variants do incur penalties, at least in the sense of a loss of prestige. Style thus becomes very important, to the extent that individual journals/publishers have ‘style-sheets’ outlining the kind of English that they will publish. If you want to know how to write for a specific situation, first get hold of the style sheet of the publisher concerned. A style-sheet will include rules on several levels: 1) The specific institution: Present papers with a cover page; no not use plastic binders, etc. These are things that will be different for each university, if not for each teacher. 2) Basic grammar: students have to be taught how to use apostrophes, since they always get them wrong - they didn’t use them when they learnt to speak. 3) Removing grammar mistakes due to spoken language: "He would have been elected," not "He would of been elected." "She could have done it," not "She could of done it." 4) Using specific conventions: In general refer to actions people did in the past in the past tense (examples: Napoleon won the Battle of Austerlitz", and "Voltaire wrote Candide"). Refer to quotations from authors in the present tense, even if the author you are referring to is a historical person (examples: "E.P. Thompson [a modern writer] says that the English working class evolved only in the 19th century," and also "Voltaire [an 18th Century author] suggests the Church of his time was corrupt.") In the last case note that you use the present tense for what Voltaire says/writes/suggests but the past tense for his description of a state of affairs in the past. 5) Avoiding features of spoken language: Words to Avoid "Incredible," "Unbelievable," "Literally," "People," "They." Always check that these words really mean something when you use them. Here we might add more recent spoken American features such as “It’s like awesome...”. "Being that he was King of France, ...." is better rendered "Since he was..,." or "Because he was...," or "When he was..." 6) Avoiding the first person: 2 Robert Laytham Visser ’t Hooft Lyceum Leiden English Department When writing formal papers only use "I" and "me" when it becomes confusing to avoid them. An essay is not meant to "sound" like a letter to a friend or a diary entry. This is actually a moot point – see below. 7) Insisting on lost causes like rejection of the split infinitive. 8) Insisting that it is ‘bad style’ to use passives. Look at the following humorous summary: HOWTOWRITEGOOD Several years in the word game have learnt several rules. 1. Avoid Alliteration. Always. 2. Prepositions are not words to end sentences with. 3. Avoid clichés like the plague. (They're old hat.) 4. Employ the vernacular. 5. Eschew ampersands & and abbreviations, etc. 6. Parenthetical remarks (however relevant) are unnecessary. 7. It is wrong to ever split an infinitive. 8. Contractions aren't necessary. 9. Foreign words and phrases are not apropos. 10. One should never generalize. 11. Eliminate quotations. As Ralph Waldo Emerson said: "I hate quotations. Tell me what you know." 12. Comparisons are as bad as clichés. 13. Don't be redundant; don't use more words than necessary; it's highly superfluous. 14. Profanity sucks. 15. Be more or less specific. 16. Understatement is always best 17. Exaggeration is a billion times worse than understatement. These features may generally be seen as repeated moves from spoken to written language. Note, however, that some of these features go in the other direction, insisting on a limited mode of writtenness. This can be seen in rejection of the first person, passives, foreign words, parentheses (i.e. syntactic complication), excessive citations, abbreviations and perhaps alliteration. Students are thus taught to avoid certain variants of spoken language, yet not to go too far into the heights of written language: academic English seeks to remain clear and understandable. [From a less generous perspective, we might observe a certain fetishism about the correctness of academic prose, especially in the United States. It is perhaps the absence of an officially recognized language academy that makes the university system more aware of its linguistic role than is the case in Europe.] Some of these points are open to debate: FIRST PERSONS AND PASSIVES 3 Robert Laytham Visser ’t Hooft Lyceum Leiden English Department The style-sheet is against first persons, since students tend to repeat “I think/feel/believe” instead of giving reasoned arguments for their positions. This may be seen as a move away from spokenness. However, English scientific prose traditionally avoids the first person, at least in the singular form. A classical solution is to talk in the plural (We find..., We believe,...) but this is now felt to be unacceptably archaic (except in cases where several people are in fact writing the text). A more common solution is to use passives in order to claim objectivity. Instead of: I found that X affected Y. scientific prose would tend to state that X was found to affect Y. The second sentence eliminates the subject and is thus felt to be more objective and ‘scientific’ (i.e. it does not depend in who I am: any researcher would presumably have found the same thing). The deletion of the first person and the use of the passive are thus closely related. And yet the style sheet we have just seen rejects both the first person and the passive. This may be hard to understand. The argument against the passive is partly ideological, since a deleted agent becomes a hidden agent, and people are thus led to think that they are powerless. But the argument is also partly syntactic, since passives with named agents are syntactically more complex. To write in the active is thus simpler and more ideologically correct. We thus find a very real movement away from the passive, reinforced by the preferences of Microsoft grammar checks. In some cases this is leading to wider acceptance of the first person, at least in fairly obvious contexts such as “I found that X affected Y”. Yet the most objective prose would still seek to avoid both the first person and the passive by using nominalization: “X affected Y”, or “X apparently affected Y”. One might imagine this as a continuum between two poles. At one end, hard objective science allows no first person, allows many passives, and eliminates all traces of spoken English. In the middle, there are few passives yet no first persons. And at the other pole, where the addressee is probably a non-expert, we find few passives, first persons, and perhaps the occasional feature of overtly spoken language (although items such as contractions are not readily accepted). 3. Text Organization Expository texts usually have a simple non-narrative structure: say what you are going to say (introduction); say it (body); state what you have said (conclusion). A written text in the humanities might have something like the following: abstract, background, argument, discussion, references (sometime called Bibliography or Works Cited). Texts reporting on empirical research will have a more complex structure: abstract. background, hypothesis, experiment design, results, discussion, (conclusion), references. 4 Robert Laytham Visser ’t Hooft Lyceum Leiden English Department Internal deictics are mostly limited to references ‘above’ and ‘below’ (“As we have mentioned above...”, “We will discuss this problem below...”). 4. Abstracts and keywords An abstract is a one-paragraph summary of an article. All scientific papers have abstracts, and it is common to provide English-language abstracts for articles written in languages other than English. There is thus a lot of demand for this particular sub-genre. Abstracts are published and read separately from the article, so that people can decide if they want to find and read the article. It is like a small advertisement, containing clear pointers about the nature and contents of the longer text. Here is a minimalist abstract of one of my own papers: Recent debates in translation studies have been marked by a variety of competing perspectives. If translation is approached from the perspective of text transfer—understood as the material moving of texts across space-time—, the relationships between these two phenomena can be seen as not only causal (texts are translated because they are transferred), but also economic (translation is one of several options for the distribution of textual resources), semiotic (translations represent acts of transfer) and epistemological (attention to transfer affects the way translations are perceived). Awareness of these relationships should open up new possibilities for strongly interdisciplinary research into the nature and history of translation. The basic structure here is: problem (first sentence), approach used here (first phrase of second sentence), finding1, finding2, finding3, finding 4 (rest of second sentence), consequences (last sentence). Note that scientific abstracts do not generally need redundant material such as “In this paper...”, “The authors found that...”, although these structures can be found in cases where the abstract is written by a person other than the author (i.e. it becomes a small review article). There is a significant degree of variation in abstracts, as can be seen in the following examples: A careful analysis of the speech of middle-class African-Americans in a suburb of Houston, Texas, indicates that assumptions that these speakers typically use only variants of Standard American English (SAE) are not universally valid. The groups surveyed are college graduates with substantial incomes, whose dominant speech style is SAE. However, even a casual survey reveals that they have preserved certain African-American Vernacular English (AAVE) in their speech. A sociolinguistic survey of such variation allows for a comparison with the AAVE employed by the working-class populations. This middle-class community also provides a unique opportunity to contrast the style shifting of middle-class AAVE with the code alternations of a group of German-English bilinguals residing in the same neighborhoods. The African-American and bilingual subject registers and sample questionnaires are appended. 5 Robert Laytham Visser ’t Hooft Lyceum Leiden English Department The above is from the field of sociolinguistics, which might be described as a ‘soft’ science aspiring to objectivity. It avoids the first person by using nominalization (analysis... indicates) and passives (the groups surveyed..., questionnaires are appended). The structure would be: previous assumptions, nature of the research, new hypothesis, plus a final note on what is in the article. The article is in American English (‘neighborhoods’ instead of ‘neighbourhoods’). The following example, from the same field, might be more typical of British academic English: It has been widely assumed that linguistic heterogeneity reflects social heterogeneity, with differences in the use of linguistic variants corresponding to social groupings and sensitive to social self-presentation in terms of one or more prestige norms. This assumption is challenged by patterns of variation within the former fishing communities of East Sutherland, Scotland. In these Gaelic-speaking communities exceptionally homogeneous single-village populations show well established patterns of intra-village and intra-speaker variation that do not correlate with such familiar social factors as socioeconomic status, sex, social network, or style, and only in a limited number of cases with age. Absence of any locally workable prestige norm (the result of geographical isolation, low literacy, dialect aberrance, and minoritylanguage enclavement) is considered as a factor in the absence of social weighting of villageinternal variants. High-proficiency, Gaelic-dominant speakers participate fully in the variation, making the obsolescence of the dialect unlikely as an explanation. Reasons for inattention to individually patterned variation within small and homogeneous speech communities are considered. Here the first person is eliminated by more frequent use of passives, especially with the opening cleft sentence (It has been assumed that...). American academic English seeks to minimize such sentence, which are regarded as a syntactic complication (the sentence might become ‘Sociolinguists have long assumed that...’). The structure of the abstract is otherwise similar to the American example. Note that the abstract gives the actual findings of the research. There is no question of narrative suspense. The following example is from a journal that discusses the English used in American universities (‘the academy’ refers to academics and scholars in general): In the academy, the dissertation has turned from being a substantive contribution to a research field to an instrument of evaluation. This has occurred because of an unfortunate shift in the academy's concept of the dissertation, the power dynamics involved in producing a dissertation, the deteriorating job market in the discipline, and the undisputed importance of the dissertation to the student's career. In order to return the dissertation to its original status, graduate program directors should educate their faculty about the history of the dissertation. Efforts to educate faculty must be accompanied by official policy changes that address the structural differences between the typical dissertation and the successful monograph, in relation to subject, writing style, language, and literature review. A final policy change would be to ensure that dissertations do not become burdened with copious and unnecessary discursive footnotes. Here there is no report on empirical research; the paper actually presents no more than a series of arguments. Yet the first person is still eliminated, in this case by nominalization and a 6 Robert Laytham Visser ’t Hooft Lyceum Leiden English Department few passives. The structure would be: what has happened, why this is bad, what should be done (the modals ‘should’ and ‘must’). Abstracts appear in special publications, usually specific to a given field. They are now used online, in databases that can be used to locate whatever has been written on a subject. Author(s): Meehan, Albert J. Title: The organizational career of gang statistics: the politics of policing gangs. Source: The Sociological Quarterly v. 41 no3 (Summer 2000) p. 337-70 ISSN: 0038-0253 Language: English Review: Peer-reviewed journal Abstract: This article examines the way in which the construction of a "gang" problem and the resulting "gang statistics" in a particular community, referred to as Bigcity, are related to the local political context and the police accommodation of political interests. In particular, the political accountability of the police impacts on police recordkeeping practices and the statistics regarding "gangs" that those records generate. The organizational career of gang statistics, from the citizen's call to the police response and subsequent record work, is examined in order to demonstrate how the recordkeeping practices of the police bureaucracy facilitate the social construction of the "gang" problem. Field research data, including calls to the police, ridealong observations, and interviews, illustrate how the politicization of the "gang" problem impacts on police recordkeeping and the social construction of "gang statistics." Given that the current concern about the nationwide growth of gangs is based on such statistics and that gang suppression efforts call for enhancing and sharing gang databases, the role of police practices in shaping gang statistics is an important issue. Descriptor: Gangs. Police sociology. Criminal statistics -- United States. Police calls and responses. Police and youth. Social constructionism. Here you can see the references not only to the journal, but to a sign of the journal’s quality as well (‘peer reviewed’ means that all the articles published have been evaluated by scholars working in this field, as opposed to other journals where you get published because you are the director’s sister-in-law). The abstract does have the phrase ‘This article examines...’, but I suggest you try to avoid such things. Note that at the bottom of the entry we have a ‘Descriptor’. This is actually a set of keywords, a series of terms that enable the entry to be located electronically. These terms should indicate the field, sub-field of the research, plus words that are very specific to the topic (in this case ‘gangs’ and ‘police’). Many journals actually print these keywords at the end of the abstract. The keywords are successful when the person looking for your article can actually locate it. 7 Robert Laytham Visser ’t Hooft Lyceum Leiden English Department The best way to learn about keywords is to use them on an internet search engine (the best at the moment seems to be google.com). We will discuss this in the practice classes next week, which I hope to have in the Multimedia room. 4. References Most publishers and journals have style sheets that give specific instructions about many aspects of style. You will find an example on the website (from St Jerome Publishing), which gives instructions concerning general policy (‘no jargon’ etc.), spelling preferences (-ize or –ise, etc.) and, most importantly, the way to cite other works (i.e. references). There are many different ways of citing references. In each case you should make sure you consult the appropriate style sheet. One of the main problems here is that literary journals tend to work very differently from the more scientific journals. The MLA is the Modern Language Association (of America). The MLA style requires you to refer to the author of a work by including just the author’s name and the page number, where appropriate. The reader will then go to the end of the paper, look up the author’s name, and find the appropriate work. The work is presented in the following order: Family name, Given name. Title. City of publication: Publisher, Year. Note the use of full stops and commas. Titles of books (and films) should be in italics (or underlined, if you do not have italics). Some literary style manuals ask you to give all this information in footnotes. This is a messy solution that is losing currency. In anything remotely scientific (including sociolinguistics!), you will be asked to use a version of the ‘author-date’ system. In this system you refer to the work in your text by giving the AUTHOR’S NAME, YEAR OF PUBLICATION and then the PAGE NUMBER where appropriate. For example (from the St Jerome style sheet): Thus, Even-Zohar (1979:77) stresses that "we can observe in translation patterns which are inexplicable in terms of any of the repertoires involved", that is ... Here the reader knows that you are referring to a work by Even-Zohar (that’s his family name), published in 1979, and you have cited from page 77 of that publication. The reader can then go to the ‘References’ section at the end of the paper, look up ‘EvenZohar’, and find: Even-Zohar, Itamar (1979) ‘Transfer and Cultural Systems’, Poetics Today 14(2):75-84. This means we are referring to an article called ‘Transfer and Cultural Systems’, published in the journal Poetics Today in 1979, in volume 14, issue (número) 2 of that year, and the article starts on page 75 and finishes on page 84. 8 Robert Laytham Visser ’t Hooft Lyceum Leiden English Department There are many variations on this model, concerning use of commas, full stops, full name of author, etc. A PIECE OF ADVICE FOR RESEARCHERS OF THE FUTURE: When you make notes on your readings, ensure that you write down the full first names of the author and the pages on which an article begin and ends. Even if a style-sheet does not require this information, some future style sheet will, and if you don’t have these details you will waste many hours trying to find them A further problem is the citation of electronic material such as websites. There are many available solutions. Basically you should take the traditional model and 1) cite the electronic address (URL) instead of the city and publisher, and 2) if there is no date on the material, indicate the date you visited the site (i.e. date of access). 9 Robert Laytham