New Mexico State - College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

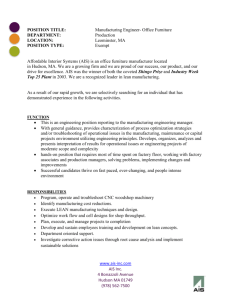

advertisement