Indefinite Detention Affirmative – ADI

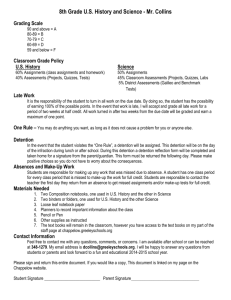

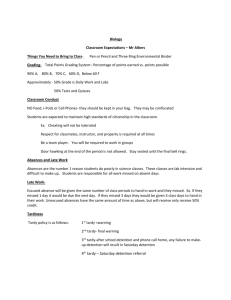

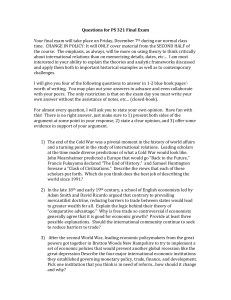

advertisement