File - Tyler Raymond Seminarian for the Archdiocese of

advertisement

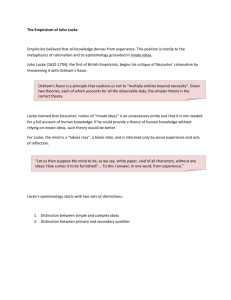

1 Tyler Raymond Modern Philosophy Fr. Joensen What can we know? Blaise Pascal and John Locke In the era of Modern Philosophy, the 17th century French Catholic Blaise Pascal and the Anglican John Locke are a complicated duo to compare for various reasons. Pascal simply lacks a really comprehensive philosophical outlook, evidenced in his most popular published (posthumously) work, the Pensees, which are simply a collection of “sentences". Locke, although he published many works that are usually lucid, generally discounts certain areas of philosophy (i.e., metaphysics), and is willing to admit lack of certitude in many philosophical debates before he discusses them. But Pascal and Locke present some interesting bases of comparison in the realm of Epistemology. Outside of political philosophy, it seems that Locke’s main interest, over and against metaphysics, is how we know, and he extensively explores this. Pascal explicates his ideas of knowledge in engaging God’s existence and our inability to know. Both Locke and Pascal put very real limitations on what we can know with very practical consequences. In the final analysis, their conclusions about whether we can know the infinite, God, is the fundamental epistemological difference. Several of Pascal’s statements are very straightforward regarding what is knowable and why. He breaks “knowability” down into two aspects: can we know the nature of the thing, and can we know that it exists (AW 107)? To know something’s nature, it must be like ours, that is, it must be limited. Things may also be unlimited, or have no “limits”, and we cannot know the nature of these things. For instance, a chair has limits (spatial and temporal at the very least) and because of this Pascal would say that we can know the “nature” of the chair. Pascal also uses the example of numbers, which are infinite, that is, unlimited and therefore, we cannot know the 2 nature of infinite numbers. We can know things about a finite number, like three. We know it is odd and that it is prime. But if we consider a number that is infinite, we cannot know these things or the “nature” of the infinite number. Pascal says that although it must be either even or odd, because all numbers are, we cannot say that it is either even or odd because we simply cannot know. Its nature is hidden from us because it has no limits. Pascal does not give a firm definition of what a “nature” is, but he associates it with “number, time, dimensions…” which suggests that aspects of a thing tells us its nature (AW 107). We will come back to this point because it involves important claims that Locke will deal with indirectly. But it seems reasonable to say that for Pascal, we can know qualities about natural objects that are limited by something, like time or space. The other relevant aspect of knowledge is whether or not the thing has extension or not. For Pascal, a thing is said to have extension if it has parts. Pascal makes this claim when he discusses why we cannot know God, neither his existence nor his nature. “If there is a God, he is infinitely incomprehensible, since, having neither parts nor limits, he bears no relation to us” (AW 107, emphasis added). We have discussed limits above in terms of number, so it is reasonable to assume that when Pascal uses the term parts, he must be referring to extension (not limit). Therefore, a chair, which has parts, has extension. The infinite number, although without limit, must actually have parts as well. Pascal does not say this, but it is the only possible explanation for how an infinite number, which is only a mental concept, has extension. An infinite number is made from the continual addition of numbers ad infinitum. It is a composite of numbers innumerable. So the chair and all numbers including infinite numbers, share extension, that is, they have parts. 3 This is different from Descartes’ definition of extension, because Descartes links extension exclusively to matter (AW 65-66), meaning that all immaterial things do not have extension. Pascal’s use of the infinite number seems to disprove this because an idea (infinite number), which is not physical, has extension by Pascal’s definition. But is there anything which lacks parts and is without extension? Pascal only explicitly places God in this category. But rather inexplicably Pascal claims that if a thing (Pascal does not distinguish between natural and supernatural) does not have extension, we cannot know that it exists. Pascal states that not only is God infinite, which makes his nature unknowable, but because he does not have parts, we cannot know by our reason if he exists or not (AW 107). Pascal does not provide any explanation as to why we cannot know the existence of a thing simply because it does not have parts, other than a lack of similarity between us and the thing, and so we must require some similarity between us and the object in order to sense it and know it. However, this may be an overextension of what Pascal would like us to take from his theory. Knowledge, which Pascal divides between “knowing nature” and “knowing existence”, can be categorized under four aspects. Is the thing in question “Infinite and Not Extended, “Infinite and Extended”, “Finite and Not Extended”, or “Finite and Extended”? Pascal gives us example of these categories. God is an infinite and un-extended; the infinite number is Infinite and extends; humans are finite and extended (AW 107). But one category is left unexplained: things which do not extend and are finite. This could include (classically) angels; beings which are not “infinite” (using Pascal’s definition) but also do not have parts as pure spirits. Pascal perhaps would say that we can know the existence of such a being because it is finite, and that God’s existence is only unknowable because he has a combination of infinitude and is simplicity. We cannot know what Pascal exactly meant, but it seems odd to say that we can know a thing 4 has parts, but we cannot know if it exists. Pascal however pushes us to this conclusion because the infinite number’s existence is knowable only through its extension. Despite Pascal’s ambiguity, we might speculate about broader epistemic claims that Pascal may have made (if he had actually finished the Pensees). Oddly enough, the first thing we can understand epistemically about Pascal’s doctrine is that there seems to an importance placed on the body, which includes the senses. “Our soul is cast into the body, where it finds number, time, dimensions” (AW 106). Pascal does not include claims of pure empiricism (knowing things exclusively through the senses), or pure rationalism (knowing things through the reason alone), and his claim that at least some knowledge is dependent upon the body, which entails experience, suggests that Pascal gives some credence to the senses. This conclusion also comes from Pascal’s work on mathematics, particularly geometry, which is used to describe relations of things in space, not ideas in our head (Broome 46). However, this is not the type of knowledge that Pascal would have deemed most important either. Pascal even says that mathematics is “useless in its profundity”, despite being one of the great mathematicians in the Modern period (Broome 47). Pascal’s main concern seems to be what we can know about God or whether he exists given Pascal’s categorization of knowledge, not the nature of things in the universe. But when it comes to knowing what we should know, Pascal’s own skepticism runs deep. Not only does Pascal say that “to ridicule philosophy is truly to philosophize”, but more astoundingly, “Pyrrhonism. Pyrrhonism is truth” (Wight 88). Pyrrhonism, which is taken up again in Michel de Montaigne in the 16th century, is a type of skepticism that does not make the claim that we can know nothing for certain, but that we do not know whether we can know anything for certain. Pascal is not only reducing the importance of knowledge of the physical 5 universe, though he does not deny it, but claims that the information he cares about, namely God, is something we cannot comprehend through philosophy! This brings us to Pascal’s Wager, which is not a claim to knowledge, but an assertion of the practical aspects of God. That is, if we cannot know either way through reason (Pascal has already asserted that we cannot know the existence nor the nature of God because he is infinite and not extended), then we are left with a dilemma: God may exist or he may not, but how should we act (AW 107)? This does not relate directly to Pascal’s theories of knowing essences or God, but it displays the epistemic limit of human cognition. Locke is more focused on the natural realm. “To ask at what time a man has first any ideas is to ask when he begins to perceive- having ideas and perception being the same thing” (AW 324). Already we have a concept of how knowledge occurs. But Locke also tells us what things can be objects of our knowledge. He enumerates four different methods of gaining what he calls “simple ideas” (AW 329). (1) “Through our senses only”; which would include sights, smells, and physical touch. Color then, is a simple idea, coming into our mind through the one sense of sight. (2) “Through more than one sense”, such as extension in space (different from Pascal’s extension!) (AW 330). (3) Through reflection (like willing); and (4) through sense and reflection (like pain and pleasure). For Locke simple ideas correspond to objects whether from senses or located in our mind. But Locke also makes distinctions between qualities that are merely objects of our mind and qualities that are actually in the objects we are perceiving. Locke labels the first kind, “primary qualities”, qualities “Utterly inseparable from the body in whatever state it is” (AW 333), and “secondary qualities, “which in truth are nothing in the objects themselves but powers to produce various sensations in us” (AW 333). Locke’s examples of primary qualities are 6 “solidity, extension, figure, and mobility” (AW 333). These are qualities which endure despite any alteration of the object. Locke gives the example of a grain of wheat, which can be divided until it is insensible, but must still maintain these qualities. The other quality, secondary, are not qualities which are proper to the object, but powers of the object “to produce various sensations in us by their primary qualities.” Color, sound, taste are all secondary qualities. A rock may be painful when it hits us, but pain is an idea in us, not in the rock. Though the rock’s primary qualities, such as solidity, may be the source of its ability to produce secondary qualities in us, they are different. Both secondary qualities and primary qualities are gathered through our perception. As to how these qualities enter our minds as ideas, Locke makes a claim that modern science meshes with very well. “Some motion must be continued from [the object] by our nerves…to the brains…there to produce in our minds the particular ideas we have of them” (AW 333). We can see objects at a distance and Locke suggests that there must be some kind of particle, which is itself imperceptible, which transfers the information to our sense organs and from our senses to our brains. Today we would use the langue of the photon, which is not a part of the object that it is revealing to our senses, but our brains interpret what we are “seeing” and give us an image. Now, when Locke talks particularly about not just knowing qualities but knowing substances (how can we know the object we are seeing and not merely the photons we are perceiving), he takes a firmly agnostic stance. If we again affirm that the source of our simple ideas are qualities of things, primary or secondary, then we know that what we actually perceive are qualities, not the things themselves. Because qualities correspond to things (we receive sensation passively, that is, something must make us sense), there is a real entity outside of ourselves, whose qualities are putting ideas into our heads, and this entity we generally refer to 7 as a substance: the “substratum” that binds the qualities together in an individual, or the combination of simple ideas that always go together in our perception (AW 359). But the problem is we cannot be sure of anything other than individuals and their qualities, because to make broader claims about connections apart from qualities is to engage in complex abstraction (AW 359). If we eat things and every time we do we perceive redness, sweetness, firmness, juiciness; we may connect the things we eat together. We may call anything that is sweet, red, firm, and juicy, an apple. We have not perceived the “nature” of apple, but we reduce the thing we perceive to its qualities, and when we perceive similar sets of qualities we group the thing perceived with our previously perceived objects. Therefore, we can use universal terms, like apples; and say things like, “all apples are fruits”, but this step outside of describing qualities is an abstraction that does not necessarily correspond to the actual thing (AW 378). Therefore, although Locke cannot deny the existence of real essences, we cannot talk about them in any real way. Instead, we are limited to employing what Locke calls “Nominal Essences” (AW 380). Nominal essences are not useless, they allow us to articulate our experience of the world (“horses don’t “baaa”). But when it comes to the reality of things, whatever “substance” underlies them, Locke remains an agnostic. He cannot prove the existence of real essences using his framework, but our senses hint at them, so there must be some sort of underlying “substance” which qualities are attached to for our sensation. This is a logical extension of Locke’s epistemology, not an empirical observation. Substances cannot be observed empirically. But there is one substance that is beyond anything in nature, God, and Locke is both agnostic about God’s existence through his method of epistemology, but certain of his existence. Because of Locke’s earlier claim that “We know nothing beyond our simple ideas”, the notion 8 that we can naturally know God, who Locke then claims is a complex idea and “incomprehensible”, seems like a cut and dry case (AW 365). But recall that Locke doesn’t think that complex ideas are totally unknowable, but knowable through their parts. For instance, when we have an idea of God, we are merely combining and abstracting ideas such as “existence and duration, of knowledge and power, of pleasure and happiness” (AW 365). Duration and existence are extended out to mean eternal and infinite, knowledge and power become omniscience and omnipotence, and so on. Locke however, believes that we can know that God exists, which may be a form of certain knowledge departing from a purely empiricist model. Although this may call into question Locke’s firm empiricism, we know that God exists not because we perceive him with our senses, but by making the rational inference from the things I perceive which are contingent, to a yet unperceived and non-contingent being who caused these things (Bluhm 417). So Locke himself is presenting an idea of knowing God that requires a form of knowledge that reaches beyond his empiricism. We come up with ideas as to what God is based on abstraction, and we can prove God’s existence based on rational demonstration. This does not deny that our knowledge comes from some type of sensation (Locke still attributed intuition and demonstration to ideas we get from perception, although they do go through abstraction (AW 389)), but reasoning plays a very important role in our ability to know God. This is far different from the way that we come to know natural or material things, but affirms Locke’s previous claim that we cannot know substances though we can infer their existence based on their qualities. So there are two different types of knowledge that Locke and Pascal deal with. The first kind is whether or not we can know substances which are not God. For Pascal this means substances that either have extension or are limited, or a combination of them. Pascal does not 9 go into further detail regarding substances, but it does seem that we can in fact know such things. Pascal does not develop a nuanced rationalist epistemology, but he does say that we can know natures of things if they are limited. As to what these natures are Pascal does not explain but there seems to be certain knowledge of real essences. Locke would not agree. Because all we can perceive for Locke are qualities of a thing, we can only talk about the nominal essences of things. Things that share certain characteristics may be said to be the same kind, but to claim that there is any sort base or underlying real essence is unsubstantiated. Locke abstracts from sensation to logically conclude the existence of substances, but they cannot be perceived, only their qualities. But when it comes to God, as discussed above, it is clear that Locke thinks we can have certain knowledge of his existence and even knowledge of some of his traits. We can know he exists through causal arguments (among others), and even that his existence is taken for granted. But we can also know aspects of God through abstraction. We come to an idea of God based on qualities we perceive from objects in the world and then abstract them. This gives us a positive knowledge of the infinite, and allows us to understand some of God’s attributes. Pascal would disagree. Again, based on his categories of knowledge, God cannot be known naturally, neither his essence nor his existence. Pascal claims that through reason, we must be purely skeptical about God’s existence. If he existed, we could not know his essence. This leads Pascal to the wager. For Pascal wants us to believe in God, but knows that we cannot. Pascal suggests that this is because God is completely different from us, meaning that we must share some sort of ontological similarity with a thing to know it. Locke does not seem to have this problem, and sees God as more related to Man than Pascal. But because Pascal wants to 10 maintain God’s complete sovereignty and transcendence from nature, he must conclude that by nature we can know nothing about God, not even his existence. What is most interesting is that Locke would also agree that we cannot have certain knowledge of God’s nature in an empirical sense. First of all, we do not perceive God. Qualities from natural objects suggest ideas about God to us, but these are simply ideas that we associate with God, not ones that God implants in us. Again, Locke is not allowing God any more leeway metaphysically than he is with natural objects. We cannot know God’s substance, so we must work from sensations that suggest God exists. Locke and Pascal would agree that we cannot know things about God by perceiving God’s essence, because his essence according to both philosophers cannot be perceived. But Locke and Pascal are firmly opposed on proving God’s existence through reason. Locke affirms reason’s ability to prove God’s existence and backs it up with a first cause argument and claims it is self-evident; Pascal disagrees because God is too utterly foreign, having neither extension nor limits. Locke demands we accept God’s existence by reason; Pascal claims we can only know him by faith. These two philosophers, despite their different methods of knowledge, come to some agreement. Unlike other continental philosophers, Pascal does not talk about innate ideas, or the exclusive truth claims of reason over perception. Locke’s critiques therefore generally do not apply to Pascal, at least on the surface. It is their conclusions about God’s existence that do not match easily. But the perception of objects in the natural world also separates them. Locke and Pascal disagree over whether we can know essences; Pascal saying yes if they are like ours, while Locke says only nominally due to the nature of perception. Pascal says God cannot be known to exist or his nature, while Locke claims reason forces us to acknowledge God’s existence, and postulate on his nature. Both men are mixtures of doubt and certain knowledge. 11 Bibliography Ariew, Roger, and Eric Watkins. Modern Philosophy: An Anthology of Primary Sources. 2nd ed. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Pub., 2009. Print. Bibliography Bluhm, William T., Neil Wintfeld, and Stuart H. Teger. "Locke's Idea Of God: Rational Truth Or Political Myth?." Journal Of Politics 42.2 (1980): 414. Business Source Premier. Web. 18 Nov. 2014. Broome, J. H. Pascal. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1966. Print. Wight, O. W., trans. The Thoughts, Letters, and Opuscules of Blaise Pascal. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1866. Print.