Benchmarking in European Higher Education

advertisement

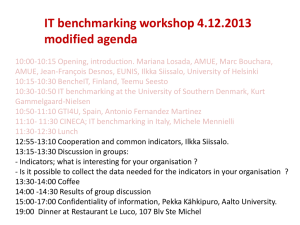

BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR Benchmarking in European Higher Education Introduction For most institutions of higher education the desire to learn from each other and to share aspects of good practice is almost as old as the university itself. With the emphasis on collegiality and the recognition of the international role of the university such desires have traditionally manifested themselves in numerous ways: professional associations, both academic and non-academic, meeting to share common interests; numerous visits by delegations from one higher education system to examine practice in another; professional bodies working collaboratively with institutions in supporting academic provision and mediating standards; and where formal quality assessment or accreditation systems exist. Thus improving performance by collaboration or comparison with other universities is nothing new in higher education. What is new, however, is the increasing interest in the formalisation of such comparisons, and this lets to one recent innovation in this area: the development of benchmarking in higher education. Arising as it does from other initiatives concerning both the enhancement and assurance of quality and the drive to increase the effectiveness of university management, benchmarking is directly relevant to current UNESCO concerns as described in its policy paper 'Change and Development in Higher Education' (1995). Definition 1 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR Benchmarking has proved to be an effective method for identifying the best practices and improving the quality and processes in an organization. The technique has been used widely in business and industry for couple of decades, and within a decade the concept has been broadly embraced and applied in higher education. The application of quality and its related concepts has led to the emergence of many successful corporations and firms around the world in the decades of 1980’s and 1990’s. As a result of this corporate revolution or phenomenon, educational organizations such as colleges and universities in many parts of the world believe that this phenomenon is applicable to them also, and thus they readily join the bandwagon. In the literature different definitions of benchmarking are used, referring to different ways in which the process of benchmarking runs or to the content of the benchmarking (see among others Eight Meier & Simpson, 2005; Appleby, 1999; Camp, 1989; Francis & Holloway, 2007, Jackson, 1998; Schoffield, 1998). In their project "Benchmarking in European Higher Education", the European Centre of Strategic Management of Universities (ESMU) gives the following definition of benchmarking: "Benchmarking is the voluntary process of self-evaluation and improvement through comparing systematic and collaborative practices and performances in similar organizations as strengths and weaknesses to discover and learn how organizational processes to adapt and improve '(ESMU, 2008). A process were the indicators are determined in consultation (mix of qualitative and quantitative data): In the benchmarking process the institutes work together to learn from each other. In collaboration they determine which indicators or data are used in the process. The data and information collected can be of different nature. The benchmarking process can use both quantitative and qualitative data. There may be quantitative data such as performance indicators collected, but also qualitative data such as reviews of processes (ESMU, 2010). Application of benchmarking in HE Traditionally, educational organizations are natured for spreading and sharing of knowledge collaboration in research and, assistance to each other. Several authors advocated that benchmarking is more suitable in higher education than business sector, due to its collegial environment, which encourages easily to collaborate and cooperate (Bender and Schuh, 2000; Alstete, 1995; Schofield, 1998). As Schofield (1998) says despite increasing market pressures, higher education remains an essentially collaborative activity with institutions having a strong tradition of mutual 2 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR support. Alstete (1995) says, due to its reliance on hard data and research methodology benchmarking is especially suited for institutions of higher education in which these types of studies are very familiar to faculty and administrators. 3 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR Improving the quality of education in Europe. Higher education is crucial to Europe's ambitions to be a world leader in the global knowledge economy. The Europe 2020 Strategy aims to support the further modernisation of European higher education systems, to allow higher education institutions to reach their full potential as drivers of human capital development and innovation. In order to respond to the demands of a modern knowledge-based economy, Europe needs more highly skilled higher education graduates, equipped not only with specific subject knowledge, but also the types of cross-cutting skills – such as communication, flexibility and entrepreneurial spirit – that will allow them to succeed in today's labour market. At the same time, higher education institutions must be able to play their full part in the so-called "knowledge triangle", in which education, research and innovation interact. The education benchmark for 2010 to increase the number of mathematics, science and technology graduates by at least 15% over 2000 level and the Bologna process objective that, by 2020, 20% of all university graduates should have undertaken learning mobility as part of their university education. When it comes to funding, the European Commission has proposed an objective that 2% of GDP should be spent on higher education. The Modernisation Agenda for Higher Education and the Bologna Process The EuropeanCommission presented an over-arching strategy for European higher education in its 'Modernisation Agenda for universities: education, research and innovation' Communication of 2006. The Modernisation Agenda sets out three core priorities: curriculum, governance and funding reform. The issue of degree structure and curriculum reform was established as a key priority with the intergovernmental Bologna Process. Launched with the signature of the Bologna Declaration in 1999, the Bologna Process aims to create a European Higher Education Area, in which national higher education systems are more coherent and compatible. 47 European countries now participate in the Process, which has expanded in scope and geographical coverage over the years since 1999. On 28-29 April 2009, Ministers 4 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR responsible for higher education met in Leuven/Louvain-la-Neuve to establish the priorities for European Higher Education until 2020. The importance of lifelong learning, widening access and mobility were underlined. The goal was set that by 2020 at least 20% of those graduating in the European Higher Education Area should have had a study or training period abroad. The Ministerial Anniversary conference, held in March 2010, confirmed the priorities set the year before but acknowledged that some of the Bologna aims and reforms have not been fully implemented and explained and that an increased dialogue with students and staff is necessary. Ministers committed to step up efforts to accomplish the reforms to enable students and staff to be mobile, to improve teaching and learning in higher education institutions, to enhance graduate employability, and to provide quality higher education for all. A Bologna Process Stocktaking Report 2009 was produced for the ministerial meeting in April 2009. For each Bologna country the report has a scorecard showing performance in 10 indicators on a scale from dark green (best performance) to red. The indicators for the 2009 stocktaking were designed to verify whether the original goals of the Bologna process - which were expected to be achieved by 2010 - were actually being achieved in reality. Whereas in 2005 it was sufficient to show that work had been started, and for the 2007 stocktaking it was often enough that some work towards achieving the goals could be demonstrated or that legislation was in place, in 2009 the criteria for the indicators were substantially more demanding. Investment in higher education The economic crisis, which has resulted in sometimes drastic cuts in higher education budgets, has had an impact on many higher education systems. The full extent of effects still remains to be seen, which will make further monitoring and analysis important. Whilst no specific target for investment has been agreed at European level, the European Commission has repeatedly stressed that in order to fulfill their potential, universities and other higher education institutions need to be adequately funded, and at least 2% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) should be invested in a modernised higher education sector, public and private sources combined. Current levels of investment are substantially below this level: 1.2%, for the EU as a whole, of which public investment accounts for by far the largest part, about 1.12% of GDP (due to data lag these figures do not take into account recent 5 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR cuts in budgets). Levels of investment in higher education vary significantly between Member States, for example, in Denmark, public spending on higher education already surpasses 2% of GDP ; a large share of this, however (as in Finland and Sweden) is direct financial aid to students and direct public spending on higher education institutions in these countries is hence considerably lower. Seven EU countries have a share of direct public spending below 1%, including Italy, Spain and Romania. Meeting the Europe 2020 headline target The new Europe 2020 headline target for tertiary attainment levels among the young adult population foresees that by 2020 at least 40% of 30-34 year olds should hold a university degree or equivalent. In 2009, 32.3% of 30-34 year olds in the EU had tertiary attainment, compared to only 22.4% in 2000. The trend since 2000, shown in Figure 2.8, suggests it will be possible to reach the target level by 2020. However, Member States' targets, as set out in their first provisional National Reform Programmes, are by and large very cautious and would lead to a lower rate of progress and possibly failure to meet the target by 2020. In 2009, eleven EU countries had already exceeded the 2020 target of 40%. Ireland, Denmark, Luxembourg and Finland show the highest tertiary attainment, with rates of over 45%. Southern European countries (with the exception of Spain) and Central European countries, despite the fact that they have very high secondary education completion rates, tend to lag behind. Progress in tertiary attainment rates in the period 2000-2009 was strongest in Luxembourg, Ireland and Poland (more than 20 percentage points increase). Types of benchmarking Alstete (1996) identifies four categories based upon the voluntary and proactive participation of institutions, to which a fifth (the so-called 'implicit benchmarking') might be added to cater for situations where the initiative for some variant of benchmarking within higher education results from the market pressures of privately produced data, from central funding, or from co-ordinating agencies within individual systems. 6 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR These types are: 1. Internal benchmarking in which comparisons are made of the performance of different departments, campuses or sites within a university in order to identify best practice in the institution, without necessarily having an external standard against which to compare the results. This type may be particularly appropriate to universities where a high degree of devolvement exists to the constituent parts of the institution, where a multi-campus environment exists, or where extensive franchise arrangements exist whereby standard programmes are taught by a number of partner colleges in different locations. 2. External competitive benchmarking where a comparison of performance in key areas is based upon information from institutions which are seen as competitors. Although initiatives of this kind may be potentially very valuable, and have a high level of 'face' validity amongst decision makers, the process may be fraught with difficulty and is usually mediated by neutral facilitators in order to ensure that confidentiality of data is maintained. 3 External collaborative benchmarking usually involves comparisons with a larger group of institutions who are not immediate competitors. Several such initiatives are reported below, and the methodology is usually relatively open and collaborative. Such schemes may be run by the institutions themselves on a collective basis, although in other cases a central agency or consultant may administer the scheme in order to ensure continuity and sufficient momentum. 4. External trans-industry (best-in-class) benchmarking seeks to look across multiple industries in search of new and innovative practices, no matter what their source. Amongst some practitioners this is perceived to be the most desirable form of benchmarking because it can lead to major improvements in performance, and has been described by NACUBO (North American Colleges and Universities Business Officers) as "the ultimate goal of the benchmarking process". In practice, it may be extremely difficult to operationalise the results of such cross-industry comparisons, and may also require a very high level of institutional commitment to cope with the inevitable ambiguities that will result. Outside the USA little use of this approach is reported within higher education, and it may be that some universities will wish to participate in inter-university benchmarking before considering this more ambitious approach. The benchmarking process 7 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR Benchmarking process models and methodologies are various with different number of phases from four steps to 20-30 steps. Camp (1989b) suggested a ten-step generic process for benchmarking. In higher education, Alstete (1995) suggested four-step approach: Plan-Do- Check-Act (PDCA) as shown in below figure (Watson 1993, Alstete 1995). Benchmarking is a learning process in which an institution gets insight into its strengths and weaknesses, determines what can be improved and assess whether these improvements have been applied. Especially when an institution pursues improvement processes of strategic plans, a benchmarking process can add value. 8 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR STEP 1: Decide to benchmark An institution chooses to benchmark as: - They want to know where she stands in terms of certain strategic themes and how they can improve; - She wants dialogue with and to learn from other institutions; - She herself wants to evaluate by comparing with other institutions using jointly developed indicators and this data wants to collect and exchange with other institutions; An important factor for successful benchmarking is the will of the institution to learn and improve by actually change and to take action. The benchmarking should have a clear focus, this means that there must be a clearly defined theme. The theme must be strategically important, feasible and sufficiently challenging. The focus is on what is important to the stakeholders of the institution, such as staff or students. What are the main needs in the institution that must be addressed and where improvement is possible? STEP 2: Partners commit to participate in the benchmarking process The selection and engagement of partners is a key factor for the effectiveness of the benchmarking process. Institutions taking part in a benchmarking process voluntary. They must be willing to exchange information, learn from each other and improve their own practice. It is crucial to find a balance between similarities and differences with the benchmarking partners. With partner institutions that are similar, the institution can more easily identify and compare. However, a certain degree of variation can lead to interesting and fertile equations (Hämäläinen, Dorge Jessen, Kaartinen-Koutaniemi, & Kristofferson, 2003). Practical tips for finding partners: 9 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR - http://www.u-map.eu/ U-Map is an ongoing project in which the European classification of higher education institutions is further developed and implemented. U-Map offers you two tools to enhance transparency. ProfileFinder produces a list of higher education institutions (HEIs) that are comparable on the characteristics you selected. ProfileViewer gives you an institutional activity profile you can use to compare three HEIs. - It may also be useful to involve outsiders in the benchmarking process. They can: - Give feedback on the various phases of the benchmarking process; - Advise on the development of indicators for the defined themes; - Advice on change; - Possibly also coordinate and/or supervise the entire process. STEP 3: Define the theme and translate into indicators and benchmarks The first task of the benchmarking group is defining the theme. This can be done through dividing the theme into sub-themes. The number of sub-themes is depending on the time and the energy that the institutions want to invest in the whole process. To keep the comparison clear and manageable there should be not too much or too little subthemes. A rule is that no more than seven sub-themes or aspects may be selected (see van Vught et al, 2010, p. 17). Then the sub-themes must be translated into indicators. The indicators determine how the various (sub-) themes can be 'measured'. The participants decide which indicators are relevant for mapping the subthemes. The first step is a brainstorm where it is important to formulate as many indicators. In the final determination of the set of indicators is the feedback from the institutions and the feasibility of the indicators important to collect the data. 10 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR Each indicator included in the exercise should be well defined. This is necessary to avoid that the indicators are susceptible to various interpretations whereby the comparability would be compromised. The development of the indicator may on the basis of an indicator card. The indicator card contains several sections that help to clearly defining the indicator. Top of the indicator card is always the theme and the sub-themes. Then follows the indicator. The indicator should be clarified by various elements: - Importance of the indicators? Benchmarks for the indicators? Levels of the indicators? Sub-theme XXXX Indicators Levels 1 2 3 4 Indicator 1 Indicator 2 Indicator 3 A good practice or benchmark implies level 4. Summary of the scores on the indicators: cross your overall score (based on the scorecards) and specify the distribution of the scores on the various aspects again. What are your goals for the course? Give color to what level the program wants to achieve. 11 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR - Possible data sources for the indicators? For each (sub) theme is a benchmark of good practice provided. STEP 4: The 'score' of the institution: data collection and interpretation At this stage of the benchmarking process gather the participants in their own setting data (qualitative and quantitative) and they assess their own performance and operation. The settings are based on their data after how they position themselves with regard to the benchmarks. Subsequently, the institution has its relative strengths and weaknesses analysis and proceed to the elaboration of an action plan. 12 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR STEP 5: Analyzing the data and drawing up an action plan Once the institution has determined to what improvements they want to work, they set up an action plan. The challenge is to draw the action plan so that it is manageable and the proposed actions can be performed. In an action plan, different elements are addressed: - What does the institution improve? What is the purpose? - What are possible steps to reach the goal? - By when should the plan be implemented? - Who is responsible for the action plan? - Who performs the action plan? - What resources should be provided? - What actions are taken? Why or why not? 13 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR 14 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR General benchmarking practices conducted by national and international agencies Generic benchmarking processes are used by several agents and organizations: Commonwealth Higher Education Management Service (CHEMS) Benchmarking Club was formed in 1995 with the aims of: to identify and promote best practices; to share ideas and increase awareness of alternative approaches; to gain benefit from an international base of experience and innovation; to learn benefit from an international base of experience and innovation; to learn from others what works and what does not; to research, and continually improve, ways of comparing with each other (Wragg, 1998). CHEMS is the management consultancy service of the Association of Commonwealth Universities. Garlick and Pryor (2004) says that the CHEMS club enables participating universities to compare their management practices and processes (e.g. strategy, policy, human resources, student support, external relations, and research management) against a range of comparable institutions. http://www.temarium.com/wordpress/wp-content/documentos/Schofield.-Benchmarking-in-HE-anInternational-Review.pdf#page=62 Another recent benchmarking project conducted by ESMU (European Center for Strategic Management of Universities) in Belgium. Although the key benefits of benchmarking are well-known, there is still a significant gap in the use of benchmarking practices in European HEIs. Indicators and benchmarks are needed by university leaders to make informed choices for strategic developments and support the competitiveness of HEIs on the international scene. http://www.esmu.be/benchmarking.html 15 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR http://www.education-benchmarking.eu/ http://www.education-benchmarking.eu/project.html EFQM (European Foundation for Quality Management) Excellence Model is being applied in higher education in Europe. The EFQM Excellence Model is a framework for organizational management systems, promoted by the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM) and designed for helping organizations in their drive towards being more competitive. Regardless of sector, size, structure or maturity, to be successful, organizations need to establish an appropriate management system. The EFQM Excellence Model is a practical tool to help organizations do this by measuring where they are on the path to excellence; helping them understand the gaps; and then stimulating solutions. http://www.efqm.org/ UNESCO fosters innovation to meet education and workforce needs and examines ways of increasing higher education opportunities for young people from vulnerable and disadvantaged groups. It deals with cross-border higher education and quality assurance, with a special focus on mobility and recognition of qualifications, and provides tools to protect students and other stakeholders from low-quality provision of higher education. UNESCO promotes policy dialogue and contributes to enhancing quality education, strengthening research capacities in higher education institutions, and knowledge sharing across borders. http://www.unesco.org/new/en/education/themes/strengthening-education-systems/highereducation/ http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0011/001128/112812eo.pdf (A study conducted by the Commonwealth Higher Education Management Service) 16 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR The European Commission's annual progress reports measure developments in education and training across the EU, using a series of indicators, benchmarks and research results. The progress reports provide strategic guidance into policy cooperation at the EU level and assess progress to overall objectives in the education and training fields. The results of these reports are used by the biannual joint reports from the European Council of education ministers and the Commission. Commission staff working document; “Progress towards the common European objecties in education and training” http://ec.europa.eu/education/lifelong-learning-policy/indicators10_en.htm http://ec.europa.eu/education/lifelong-learning-policy/doc/report10/report_en.pdf 17 BIHTEK: Benchmarking as a tool for improvement of Higher Education Institution Performance, 530696-TEMPUS-1-2012-1-BE-TEMPUS-SMGR 18