When the men of the South left for War in 1861, their loved ones at

advertisement

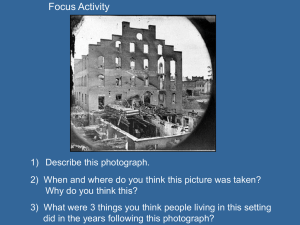

Women of the South during Reconstruction Gail Lowman Crosby Tampa 113 (Written under Fictitious Name of Eugenia Pierce Fleming June 26, 2013 1 Women of the South during Reconstruction When the men of the South left for war in 1861, most believed the conflict would end quickly. The women did not suspect the drastic changes that would overtake the entire region before the War’s end, nor could they have imagined the horrors that would befall them for a decade following the end of a long four years of fighting. During the War, Southerners endured a serious lack of everyday necessities, suffered many personal losses; they lived in the shadow of impending attacks upon their homes and lives day and night. As the War continued, those on the home front were running out of everything from “hairpins to coffins,” but the greatest problem at home was the severe lack of food. As meager as homefolks were forced to live, the constant foraging for food by both armies depleted their small supplies. In addition, shortages of salt made it impossible to preserve what little meat they might have. With all items in short supply, it was said Southern women manufactured or devised a substitute for at least three-fourths of their household needs. A phrase of the day was: “Let me whisper ---- this dress, that I now wear for thee ---- was a curtain of old, from Philadelphee.” We can laugh, when, in Gone with the Wind, Scarlett sends Mammy to the attic for patterns, and then makes a dress and hat using the green velvet window curtains. (We might wonder why on earth the Yankees but not take, but left behind, beautiful velvet curtains.) Anyway – that is exactly what a Southern lady had to do, make and patch clothing from any available fabric. Most drugs and medicines were needed for the soldiers. In a desperate search for substitutes, women created many medicines; investigating every herb, plant and tree for its use. With the men away serving the army, farms were untended; stores were left without clerks, and schools without teachers. Women and children pitched in, helping with the wounded. Janet Weaver Randolph’s caring concern for others began as a child in Warrenton, Virginia, when children would fan the wounded with palm leaf fans to keep flies off and scrape sheets for lint with which to make bandages. Still, many of the sick and wounded died and were buried in Warrenton Cemetery. The locals “made wooden crosses and burned the names and regiments into the wood and put them on the graves;1” children gathered May flowers to place on graves. Union soldiers burned the markers; now they are unknown except to God. 1 Janet Henderson Weaver Randolph 1848-1927, p 4 2 The women of the Confederacy looked beyond the War’s difficulties. They identified the needs, and found a way to overcome the problems. It was the resourcefulness and determination of those ladies that helped make a strong foundation for the Confederate States of America, allowing men to leave home and join in the fight for their beliefs. That same resourcefulness and determination of the women not only made it possible for the South to survive the long and difficult period of reconstruction, but to also build grand memorials to memorialize their Cause. Monuments of marble and cemeteries where their dead rest peacefully are the legacy of women. Robert E. Lee, General-in-Chief, CSA General Order No. 9 After four years of arduous service marked by unsurpassed courage and fortitude, the Army of Northern Virginia has been compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources. I need not tell the brave survivors of so many hard fought battles who have remained steadfast to the last, that I have consented to this result from no distrust of them. But feeling that valor and devotion could accomplish nothing that would compensate for the loss that must have attended the continuance of the contest, I have determined to avoid the useless sacrifice of those whose past services have endeared them to their countrymen. By the terms of the agreement, officers and men can return to their homes and remain until exchanged. You will take with you the satisfaction that proceeds from the consciousness of duty faithfully performed, and I earnestly pray that a Merciful God will extend to you His blessing and protection. With an unceasing admiration of your constancy and devotion to your country and a grateful remembrance of your kind and generous consideration for myself, I bid you all an affectionate farewell. (Signed) R. E. Lee Gnl. The War was over – but it was the beginning of unthinkable atrocities to come during the many years of reconstruction. 3 Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation is thought by some to be the beginning of Reconstruction, yet most would use 1865 and the War’s end as the start date for that horrific time in our country’s history. Martial Law was imposed by the Union Army, rights were stripped from those who had supported the Confederacy, and unspeakable atrocities were imposed on Southerners. The actual end of what some consider the ten-year reconstruction, including eight years “radical reconstruction,” was a “staggered process.” The Union Army’s control in state governments officially ended in the last occupied states with the Compromise of 1877; an unofficial act that simply settled the “disputed 1876 U.S. presidential election,” putting Rutherford B. Hayes into the White House. Radical reconstruction came into being during 1867. Shortly after Lincoln was assassinated on Good Friday, April 14, 1865, President Andrew Johnson, a moderate on reconstruction, who believed the Union’s goals for unity and the end of slavery had been met, declared the end to reconstruction. Congress’ refusal to agree with President Johnson threw the healing of the nation into a long period of what some in the South felt was hate by the North. The South was poverty stricken. Over one-fourth of the young men had died during the War, farms had been destroyed, livestock had been killed, land had been scorched so that nothing could grow even if seeds or money with which to purchase were available for planting, the public school system was non-existent, transportation systems were in total ruin, the Confederate dollar was worthless, property taxes were high and “arbitrarily set,” there were no banks to lend money, and foreclosures were commonplace. To show the losing South who was “in charge” and to ensure constitutional rights and equality to blacks, Congress divided the Southern states into five military districts. These transitional state governments were led by Military Governors in each district. In addition to harsh military rule, the worry about putting food on the table and fears for what tomorrow might bring, Southern white women had other fears – Shantytowns and Carpetbaggers. \ Blacks, newly freed; often hungry, sick, and afraid, were living in tents and shacks on the outskirts of many Southern towns, creating fear in the hearts of white Southerners. In some instances, shantytowns were large in size with no one to enforce law and order. Slaves who had been taken care of; given food, clothing, housing, medical attention – were, all of a sudden, expected to live and act independently. 4 Northerners, with only carpetbags in hand, came South to take advantage of its citizens who were barely surviving following a War fought on their soil, then being placed under the harsh thumb of a military rule. Many carpetbaggers who made the trek South were Northern businessmen but most had served as Union soldiers. Civilians were also “lured South” by press reports of the fabulous sums of money to be made raising cotton. Not all carpetbaggers were white. Black men also felt the desire to fatten their pocketbooks by taking advantage of downtrodden Southerners. No matter who they were, they came South to buy up plantations at a small fraction of their value. Some years after reconstruction was “officially” over, Mrs. Norman V. Randolph of Virginia would tell about her old home in Warrenton. After the War, “a great many very wealthy Northern people had come down and bought up huge horse farms in the area. . . . ‘The door to Warrenton society used to be through the parlor, but now it is through the stable’.”2 In addition to Carpetbaggers buying land for a few cents on the dollar, many became involved in politics. The fact that these transplants were holding elected office and running the government was another large problem, on top of all of the other problems, the people of the South had to try and combat. Southerners lived “in a most miserable uncomfortable state, subject every day, and all day, to all manner of annoyance.3” The once prosperous South lay in devastation. Black mourning clothes were a common sight; the suffering “reflected in faces of white women.”4 Richmond’s Mrs. Randolph, who had dedicated her life to the Confederacy, told her granddaughter “that once when she was walking down Main Street in her widow’s weeds – a long black dress and veil – two gentlemen were walking behind her and one turned to the other an remarked ‘There does the Confederacy draped in black’.”5 Mrs. Randolph could not help but overhear the men and felt it sad, but true. Georgia and South Carolina felt the hardest hand of the Union Army. Many years after the war, a woman was quoted as saying: “The Yankee soldiers had ruined us. They took all the cattle and hogs and horses they could find, and took our crops – what they didn’t burn. We didn’t even have seed to plant next Spring. We lived mostly on corn bread. Sometimes we didn’t have anything else, and we wouldn’t even sit down to the table to eat. Ma would bake a 2 Janet Henderson Weaver Randolph, 1848-1927, p 3 The Civil War Diary of Anne S. Frobel of Wilton Hill in Virginia, p 241 4 Reconstruction, 1865-1877, The UDC Magazine, January 2013, p 11 5 Janet Henderson Weaver Randolph, 1848-1927, p 10 3 5 pone of corn bread and put it in the table drawer. Whenever any of us got hungry enough to eat dry bread we would go get us a piece.”6 Many families left Georgia, moving to Texas and Florida hoping for a better life that had not seen as much fighting and devastation. In a January 1986 letter, Floridian Cecil Robinson tells the story of his mother, Annie Bell Hall, who had been born on a plantation outside of Thomasville, Georgia. “They had slaves on the plantation and my grandfather fought under General James Longstreet. After the War things were so devastated that they just walked away from the plantation and moved to Florida.”7 The Halls settled in Archer. Even after surviving four long years of War, Mrs. Hall and her daughters found it hard to get by. There was no leisurely life-style in post-war Florida (or anywhere else in the South) as they had enjoyed on their Georgia plantation prior to the War. Because there had been a strong Union presence in the Gainesville/Archer area during the War that presence continued during after the War had ended. Reconstruction was the awful beginning of a new life. Women continued trying their best to get by day-by-day, almost in the same way they had struggled during War except there was the absence of actual military combat. During the War, the women of the South had banned together in their communities, forming Ladies Aid Societies whose goal was to help the War effort, giving what little food and items of a material nature they could. By forming groups, they could accomplish more than working singly. The meetings of the Societies also served as therapeutic healing sessions from the wages of War for women who lived far apart, having little opportunity for contact with neighbors. One example of the work of Societies is Caroline Douglas Meriwether Goodlett, who later became co-founder of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. She “put everything aside and exerted all her energies to aid the South; she converted her rooms into places where the women met to sew, knit, and make bandages and clothing. Oftentimes wounded soldiers were cared for until they could be removed to a hospital.”8 At the end of the war, with the extremely difficult reconstruction in place, “they clung to their pride and dignity, for it was all that remained in their devastated wasteland. They were reduced to a frontier society and had to constantly struggle to stay alive.”9 Never-the-less, 6 Tampa Tribune, Dec. 4, 1955 Robinson letter, January 23, 1986 8 The Courageous Caroline, p 28 9 UDC Magazine, January 2013, p 11 7 6 Southern women went out into their communities as part of the Ladies’ Memorial Associations which was a way to express dedication to their Southland and The Lost Cause. Many existing Societies transitioned into Ladies’ Memorial Associations and new Associations were created throughout the South, the first being organized in Winchester, Virginia. Many women, who had done the work of men during the War, found it necessary to continue running farms or plantations, taking care of a family under the most trying of circumstances. Still they put many hours into the Ladies’ Memorial Associations whose work was two-fold. Their immediate goal was to continue, as they had during the War, gathering and giving proper burials to Southern dead. The women would gather up bodies from along the roads; they would remove those buried in graves so shallow the entire body was not covered with dirt, and give them proper burials. This courage, devotion and loyalty gave the ladies strength to establish cemeteries. No matter how hard daily life was, the women and children would tend the graves of the Southern soldiers. The second part of the Associations’ work came later during reconstruction, and that was to raise monuments in honor of those who had served. As early as 1866, Union soldiers’ bodies were removed from across the Southland and transported to Arlington where they were buried in the United States National Cemetery. Southerners felt it inappropriate that the U.S. Government cared only for making sure Union soldiers received proper burial, leaving Confederate soldiers where they were. This lack of respect by the U.S. for the Confederate dead sparked even more interest in the creation of Ladies’ Memorial Associations throughout the South. A custom was born in Columbus, Georgia when a Society visited the local cemetery to tend graves of soldiers. That act gave way to the setting aside of one day each year to honor the departed by placing flowers and greenery on the graves. The positive response to letters sent by the Georgia Society to other Ladies Aid Societies suggesting the practice of remembering the departed annually was overwhelming. Mrs. Logan, wife of Union General John Logan, National Commander of the Grand Army of the Republic, saw Virginia ladies tenderly tending graves. After sharing the moving experience with her husband upon her return home to Washington, D.C., General Logan issued his General Order No. 11 on May 5, 1868 proclaiming that one day each year be set aside to decorate graves of each soldier. Confederate Memorial Day was first observed on May 30, 1868 when graves of Union and Confederate soldiers were decorated at 7 Arlington National Cemetery. A portion of General Order No. 11, the genesis that spawned this country’s Memorial Day on May 30th each year, reads: The 30th day of May, 1868, is designated for the purpose of strewing with flowers or otherwise decorating the graves of comrades who died in defense of their country during the late rebellion, and whose bodies now lie in almost every city, village, and hamlet churchyard in the land. . . . Let us, then, at the time appointed, gather around their sacred remains and garland the passionless mounds above them with choicest flowers of springtime; let us raise above them the dear old flag they saved from dishonor; . . .. As though living under a tyrannical government rule, existing day-by-day under the most trying of circumstances, burying the dead, and dealing with the hundreds of other obstacles on a daily basis were not enough, the Spartan women of the South went about building monuments to those who had fought hard, against all odds, for The Lost Cause. The women would work tenaciously for years to earn the money, a penny here, a penny there, to build monuments and then place them in such conspicuous places as town squares. The first monument to the Confederate States was dedicated in Kentucky on the site of the Battle of Cynthiana. A group of women formed The Cynthiana Confederate Monument Association and, in 1869, “spearheaded” the project to build the monument. A Ladies’ Monumental Association in South Carolina published a newsletter promoting plans to build a Confederate Monument dedicated to those who lost their lives in the war. The Confederate Memorial located on the grounds of the Alabama State Capitol required many years of fundraising and memorializes all branches of the service. The works Southern Women accomplished following the war, while continuing to face untold daily hardships, are not forgotten. The tenacity and spunk of those women that allowed them to achieve the almost unbelievable under such trying circumstances, we, in the year 2013, could never fully comprehend. Helping to unite their Southern brothers and sisters, tending the farms, keeping families together and keeping the hearth fires going, they also gave the dead proper burials, established cemeteries, and “built monuments to commemorate the struggle in marble and bronze.” Their caring, loving goodness has been handed down through glorious benevolent works; graves are still being decorated; monuments tended and the country remembers on Memorial Day those who made the ultimate sacrifice. 8 Bibliography Women of the South During Reconstruction Books Ayers, Janet Randolph Turpin Janet Henderson Weaver Randolph, A Granddaughter’s Reminiscences Coski, John M. Mrs. Norman V. Randolph Challenge the Stereotype of a “Confederate Woman” Frobel, Anne The Civil War Diary of Anne S. Frobel of Wilton Hill in Virginia Hicks, Robert The Widow of the South Moore, Frank Anecdotes, Poetry, and Incidents of the War: North and South: 1860-1865 Moore, Frank The Civil War in Song and Story, 1860-65 Turner, Josephine M. The Courageous Carolina Wilkinson, O.G. & Joyce Last Resting Place; Tullahoma’s Confederate Cemetery Magazines The Museum of the Confederacy Magazine, Summer 2007, The Life & Career of Mrs. Norman V. Randolph UDC Magazine, January 2013, pp. 11-14, Reconstruction, 1865-1877. The Bulletin, The United Daughters of the Confederacy, Volume IV, June 1941, No. 6, p.8, History of the Mrs. Norman V. Randolph Relief Fund News and Notes from the Fauquier Historical Society, Vol. 26, No. 1, Spring & Summer 2004, pp 1-5 Loss On The Home Front Was Marked By Loss, Privation Newspaper The Tampa Tribune, Pioneer Florida, by D.B. McKay, December 4, 1955 Letter Cecil E. Robinson letter Morriston, Florida, January 23, 1986 9