Thesis is online available here

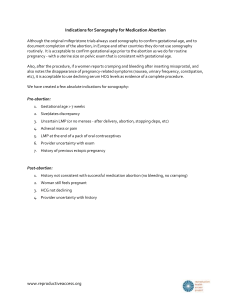

advertisement