Headache (NICE) pdf

Scottish Diagnosis and management of headache in adults

A national clinical guideline

Introduction

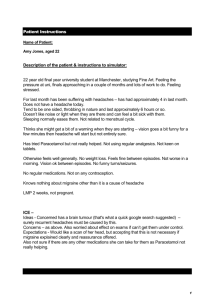

Most patients with headache who present in primary care have primary headache (e.g. migraine without aura and tension type headache). In primary headache, findings on neurological examination are usually normal and investigations are not helpful for diagnosis. The individual patient’s history is of prime importance in the evaluation of headache.

Primary Headache

Migraine:

Migraine is the most common severe primary headache disorder. The global lifetime prevalence is 10% in men and 22% in women.

A migraine headache is characteristically:

- Unilateral

- Pulsating

- Builds up over minutes to hours

- Moderate to severe in intensity

- Associated with nausea and/or vomiting and/or sensitivity to light and/or sensitivity to sound

- Disabling

- Aggravated by routine physical activity.

Migraine is classified by the presence or absence of aura. A typical aura comprises fully reversible visual and/or sensory and/or dysphasic speech symptoms. Symptoms may be positive

(e.g. flickering lights, spots, zig zag lines, tingling) and negative (e.g. visual loss, numbness).

Symptoms characteristically evolve over ≥5 minutes and resolve within 60 minutes.

Recurrent attacks lasting four to 72 hours, occur as infrequently as one per year or as often as daily. The median frequency is one to two per month. Chronic migraine is classified as migraine occurring on 15 or more days per month for more than three months. In chronic migraine the headache may have features more typical of tension-type headache.

SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS

As many as 75% of patients with migraine describe neck pain associated with migraine attacks.

Patients may present with more than one headache type.40% of patients report bilateral pain,

50% describe the pain as non-pulsating, and vomiting occurs in less than 33%.

- Episodic severe headache that causes disability

- Nausea

- Sensitivity to light during headache

- Sensitivity to light between attacks

- Sensitivity to noise

- Typical aura (in 15–33% of patients with migraine)

- Exacerbation by physical activity

- Positive family history of migraine.

When combined with assessment of functional impairment, the features which give the greatest sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of migraine are nausea and sensitivity to light.

C Patients who present with a pattern of recurrent episodes of severe disabling headache associated with nausea and sensitivity to light, and who have a normal neurological examination, should be considered to have migraine.

Tension -type headache

Tension-type headache (TTH) is the most common primary headache disorder. It has a global lifetime prevalence of 42% in men and 49% in women. The pain is generally not as severe as in migraine. The pain is typically bilateral, characteristically pressing or tightening in quality and mild to moderate in intensity. Nausea is not present and the headache is not aggravated by physical activity. There may be associated pericranial tenderness, sensitivity to light or sensitivity to noise.

Episodic tension-type headache (ETTH) occurs in episodes of variable duration and frequency.

Chronic tension-type headache (CTTH) occurs on more than 15 days per month for more than three months.

C A diagnosis of tension-type headache should be considered in a patient presenting with bilateral headache that is non-disabling where there is a normal neurological examination.

Secondary headache

Secondary headache (i.e. headache caused by another condition) should be considered in patients presenting with new onset headache or headache that differs from their usual headache.

Observational studies have highlighted the following warning signs or red flags for potential secondary headache which requires further investigation:

Red flag features:

- New onset or change in headache in patients who are aged over 50

- Thunderclap: rapid time to peak headache intensity (seconds to 5 mins)

- Focal neurological symptoms (e.g. limb weakness, aura <5 min or >1 hr)

- Non-focal neurological symptoms (e.g. cognitive disturbance)

- Change in headache frequency, characteristics or associated symptoms

- Abnormal neurological examination

- Headache that changes with posture

- Headache wakening the patient up (NB migraine is the most frequent cause of morning headache)

- Headache precipitated by physical exertion or valsalva manoeuvre (e.g. coughing, laughing, straining)

- Patients with risk factors for cerebral venous sinus thrombosis

- Jaw claudication or visual disturbance

- Neck stiffness

- Fever

- New onset headache in a patient with a history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Infection

New onset headache in a patient with a history of cancer.

Assessment tools

D Practitioners should consider using headache diaries and appropriate assessment questionnaires to support the diagnosis and management of headache.

Investigations

D Neuroimaging is not indicated in patients with a clear history of migraine, without red flag features for potential secondary headache, and a normal neurological examination.

D Clinicians requesting neuroimaging should be aware that both MRI and CT can identify incidental neurological abnormalities which may result in patient anxiety as well as practical and ethical dilemmas with regard to management.

MIGRAINE

Acute treatment

The treatment of acute migraine attacks should be selected for each patient according to severity and frequency of attacks, other symptoms, patient preference and history of treatment. A stepped approach can be used, commencing with an analgesic and anti-emetic, if required, and escalating to 5HT1 receptor agonist (triptan) as required. A non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

(oral/rectal or intramuscular) can be given following, or added to, a triptan for resistant attacks

Practitioners should recognise that a patient’s standard therapy may not give a consistent response across all attacks. A strategy for managing resistant attacks should be planned with patients.

When initiating acute treatment for migraine the risks of medication overuse headache should be discussed with the patient.

The proportion of patients who become pain free two hours post-dose has become the preferred and clinically most relevant primary end point. However, the ideal efficacy end point is sustained pain free: the proportion of patients who were pain free by two hours post-dose and who do not have a recurrence of moderate or severe headache and who do not use any rescue headache medication

Tension-type headache

Acute treatment;

Aspirin and paracetamol are recommended for acute treatment in patients with tension type headache.

High blood pressure does not usually cause headache, although blood pressure lowering treatments can reduce the prevalence of headache.

Lifestyle factors

1- Diet

Although many patients report that various foods trigger their migraine, an editorial review found no good quality published evidence to support this. No evidence was identified to support the prophylactic effect of general avoidance of cheese or chocolate, or for any other dietary manipulation in patients with migraine.

Expert opinion suggests that omission or altered timing of meals may be associated with migraine in some patients, e.g. missing breakfast may trigger a late morning attack, and so patients should be encouraged to eat regularly.

Patients with migraine should be encouraged not to miss meals.

2- Trigger avoidance

Limited and low quality evidence was identified in relation to possible trigger factors for headache. A survey of patients with headache suggested that a reduction in caffeine intake and addressing sleep problems may reduce disability associated with headache.

No good quality evidence was identified on whether mobile phone signals relate to headache symptoms.

3- Exercise

The evidence on exercise was mainly limited to exercise included in combined therapies programmes.

For patients with migraine, multidisciplinary intervention including group supervised exercise therapy sessions (along with stress management and relaxation therapy lectures, dietary advice and massage therapy) provided improvements in frequency, intensity and duration of headache and quality of life.

4- Sleep

No good quality evidence was found relating to sleep and headache. There may be an association between obstructive sleep apnoea and chronic headache, although studies did not include headache as a primary symptom. Changes in sleep pattern, e.g. sleeping longer at weekends or sleep disturbance due to stress, may be associated with migraine, although there may be confounding factors related to the altered sleep.

5- Stress management

In a prospective analysis of the factors related to headache in migraineurs, tension and stress were associated with increased risk of migraine, whereas holidays, relaxation after stress and after divorce decreased the hazard.

Multidisciplinary intervention, including stress management was effective in patients with migraine. Results from a survey of patients with migraine suggest that reduction in stress can relieve headache symptoms.

B Stress management should be considered as part of a combined therapies programme to help patients reduce the frequency and severity of migraine headaches.