References - Blogs@Baruch

advertisement

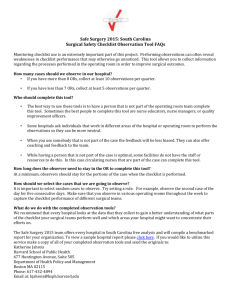

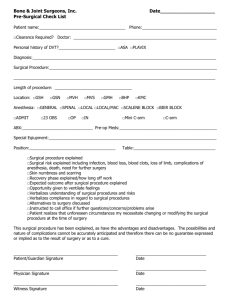

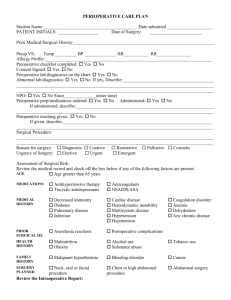

TO: Chief of Staff, Surgery and Vice President of Peri-Operative Services FROM: Maria Fezza RN BSN CNOR and Mary Dobbie RN BSN CNOR CURN RE: New Methods for Conducting Safety Checks in the Operating Room DATE: 3/7/15 Policy Options Brief Problem: Improving Patient Safety in the Operating Room The problem presented in this memorandum is: How does an organization effectively roll out a new method for conducting required safety checks in the operating room to improve compliance and increase patient safety? The use of some type of surgical checklist is required by government and state agencies. The Joint Commission established the Universal Protocol as a requirement for all accredited hospitals, ambulatory care and office-based surgery facilities in 2004. Universal Protocol requires that procedure verification be completed prior to all invasive procedures in every patient care settings. The requirement includes performing checks and a “time out” prior to starting a surgical or invasive procedure. These checks guide the surgical staff through the verification process and ensure all steps are completed. The checks include, but are not limited to: identifying the correct patient, procedure and site of procedure, implants, equipment needed, relevant paperwork, and the correct labeling identified on all the elements listed (Joint Commission, 2014). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented a quality-reporting program requiring the use of a safe surgery checklist. This measure is part of payment determination (Joint Commission, 2012, para. 1). Wrong procedure, patient, or surgical site are considered “never events”. Since 2009 CMS has not reimbursed any cost associated with these surgical errors. According to Collins, Newhouse, Porter, and Talsma (2014), “this change in reimbursement was driven by data indicating that 48% of all surgical complications are preventable” (p. 66). The State of New York Department of Health issued the New York State Surgical and Invasive Procedure Protocol (NYSSIPP) intended for all patient care settings and individual practitioners in 2006 requiring establishment of a policy and procedure for invasive procedure protocol (State of New York Department of Health, 2006). Although the application of the Universal Protocol has been mandated, there continue to be errors associated with surgery. The World Health Organization (WHO) has created guidelines to “facilitate patient safety policy and practice” globally (World Health Organization [WHO], 2009, p. 1). The guideline addressing safety of surgical care includes “Objective 9: The team will effectively communicate and exchange critical information for the safe conduct of the operation” (WHO, 2009, p. 78). Objective 9 identifies keys to a successful environment which are dependent on the surgical team conducting procedures as one unit with transparent communication. The description of this guideline is best explained in the Objective itself: “The greatest threats to complex systems are the result of human rather than technical failures. And while human fallibility can be moderated, it cannot be eliminated” (WHO, 2009, p. 78). The WHO Objective 9 suggests that without efficient consistent communication utilized by all surgical team members, the patient outcomes will be negatively impacted. A checklist provides “real time” quality assurance so any deviations from safe operative practices may be immediately rectified. In complex systems like aviation, checklists and team communication are used to ensure safety. Objective 9 aims to bring that environment of safety into the OR. The WHO checklist identifies three main phases of the intraoperative experience. Each phase occurs during a specific time period. The checklist for a particular phase must be addressed and all elements confirmed before moving to the next phase. The phases include pre-induction, which is prior to the administration of anesthesia, pre-incision or start of the invasive procedure, and immediately prior to the patient leaving the operating or procedural suite. These checklists are extremely important to patient safety and improving communication in the operating room. They “help the peri-operative staff double check important aspects of caring for patients during surgical interventions and help staff members find their own voice and have the skills to speak up if there are problems. The overall goal is to reduce errors that affect a patient’s surgical outcome” (Pashley, 2012, p. C5). It is imperative for the operating room team to act as a cohesive group in order to provide positive patient outcomes. Although hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers follow the requirements of the Joint Commission, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the Department of Health, errors continue to occur. According to the Health Research & Educational Trust and Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare (2014), from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2013 the Joint Commission sentinel event database shows that there were “463 incidents of wrong patient, wrong site and wrong procedure surgeries” (p. 4). These numbers indicate that although the Universal Protocol is mandated, there are gaps in the system. According to the Joint Commission “the number one root cause of wrong site surgery is poor communication amongst the surgical team, the second is the lack of procedural compliance, and the third is lack of leadership” (Cooper & Nitz, 2009, p. 49). The causes of poor communication include: time pressure, noise, cultural factors, lack of skills, environment, and interruptions. According to Cooper and Nitz (2009), One must first recognize the barriers to communication. Then, develop a plan to improve communication flow. Awareness and education are key, but experts are beginning to recognize that they’re not enough to solve problems. A solution to communication barriers could be engineering ways to prevent miscommunication and ensuring that no surgical procedure is started before proper communications occurs (p. 49). In improving patient safety and compliance in the operating room, an organization needs to appreciate the many levels of communication required and develop tools to enhance that communication. A properly designed and implemented surgical checklist has the ability to improve teamwork, communication, efficiency, and compliance. All of these improvements equate to enhanced patient safety. In summary, Human error caused by poor communication and lack of teamwork is the leading cause of patient harm in the surgical environment. In 2008, The Joint Commission reported that more than two-thirds of adverse events occurring in the OR were a result of poor communication. To reduce errors, studies have recommended using team training, checklists, and standardized protocols (Tibbs & Moss, 2014, p. 477). Although, adherence to government and state agency mandates have been implemented and the use of a surgical checklist has been applied since 2009, errors and patient safety concerns continue to exist. According to the WHO (2009), “currently, hospitals do most of the right things, on most patients, most of the time. The Checklist helps us do all the right things, on all patients, all the time” (slide 12). The math is easy, 234 million people are operated on each year and more than 1 million of those individuals die from complications. According to the WHO (2009), at least half of those deaths are avoidable with the Checklist (slide 28). It is important to examine the workflow and implement changes that are necessary to improve patient care, safety, and communication among the surgical team. We would like to take this opportunity to address the problem and explore new methods for conducting safety checks in the operating room. Thank you for taking the time to consider new methods for conducting safety checks in the operating room. Options: New Methods for Conducting Safety Checks in the Operating Room Option 1: A hospital wide mandated Registered Nurse (RN) Prompted Time Out supported by laminated posters to ensure all elements of the Universal Protocol are covered. Provide every operating and procedural suite with a laminated script of the RN Prompted Time Out. This laminated script would be on an 8.5 x 14 inch double sided poster to be utilized by the RN each time a surgical or invasive procedure time out is performed. The script would be based on the Joint Commission, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and the Department of Health requirements as well as hospital policy and standards of care. The RN Prompted Time Out would be mandatory and must be followed exactly as written in the same sequence every time to standardize practice. The script will include the RN prompt and the team member that is to respond to the prompt. The cost of the laminated posters is $3.06ea. Two weeks are needed to create and laminate the posters during which time education of all Surgeons, Anesthesiologists, RNs, and team members would occur. Advantages of this option include the low cost of laminated posters and short window required to implement. Other advantages include the structured format and increased team communication. Disadvantages include physician and RN buy in to the RN Prompts. Option 2: Wall Mounted Monitors to be mounted in every operating and procedural suite. These monitors would display the electronic medical record (EMR) time out section. The display would show all elements of the time out and the team member responsible for addressing each section. Every suite will require a 55 inch monitor to ensure that all team members are able to visualize the elements of the time out. Other requirements include a display mount, a computer, installation of data line, and an emergency power outlet. The anticipated cost per room is $5,500.00. Implementation will be 6 to 8 months. The first phase of implementation entails creating a budget proposal and approval. Secondly ordering all necessary equipment and ensuring each suite has proper data lines and wall space to support the 55 inch monitor. Possible minor construction and/or rearranging existing mounted equipment to support the monitor may be required. Advantages of this option include the ability to document the time out in real time and all team members having the ability to visualize the required elements of the time out. Disadvantages include the possibility of electrical shut down and the computers going down. Other disadvantages include the monitor being in a fixed location. Operating teams “frequently function in what has been termed ‘silos’ – they ostensibly work together as a team, but the worlds of surgery, nursing and anesthesia can be very different, and in some environments they barely interact” (WHO, 2009, p. 78). This working in parallel without knitting together as a team causes communication breakdown which can negatively impact patient safety. Additionally, “operating teams tend to be strongly hierarchical and team members are reluctant to communicate between hierarchical levels” (WHO, 2009, p. 78). Individualism and a hierarchical environment are barriers to cooperation and team work. “There is a strong association between structured collaboration among the surgical team members and improved OR communication, which may result in less human error” (Norton & Rangel, 2010, p.62). An organization must choose how to implement the roll out for a new method of conducting required safety checks in the operating room to improve compliance and increase patient safety. References Collins, S., Newhouse, R., Porter, J., & Talsma, A. (2014, July). Effectiveness of the Surgical Safety Checklist in Correcting Errors: A Literature Review Applying Reason’s Swiss Cheese Model. AORN 100(1), 56-79. Cooper, A., & Nitz, G. (2009, August). Will the time out champion please stand up. The OR Connection 2(1), 47-51 Health Research & Educational Trust and Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. (2014, August). Reducing the risks of wrong-site surgery: Safety practices from The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare project. Chicago, IL: Health Research & Educational Trust. Accessed at http://www.hpoe.org Joint Commission. (2012). Safe Surgery Checklist. Retrieved from http://www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/up.aspx Joint Commission. (2014). Facts about the universal protocol. Retrieved from http://www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/up.asp Norton, E.K., & Rangel, S.J. (2010, July) Implementing a pediatric surgical safety checklist in the or and beyond. AORN, 92(1), 61-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aorn.2009.11.069 Pashley, H.S. (2012, June). Implementing the AORN surgical checklist and its effect on OR culture change. AORN 95(6), C5-C6. State of New York Department of Health. (2006). New York State Surgical and Invasive Procedure Protocol. Retrieved from http://www.health.ny.gov/professionals/protocols_ and_guidelines/surgical_and_invasive_procedure/docs/protocol.pdf Tibbs, S., & Moss, J., (2014, November). Promoting teamwork and surgical optimization: Combining team STEPPS with a specialty team protocol. AORN 100(5), 477-488. World Health Organization. (2009). WHO guidelines for safe surgery 2009: Safe surgery saves lives. Retrieved from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/ 2009/ 9789241598552_ eng.pdf World Health Organization. (2009). WHO safe surgery saves lives speakers’ kit. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/speakers_kit/en/