Week 7 – Writing Horror

advertisement

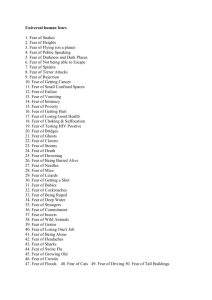

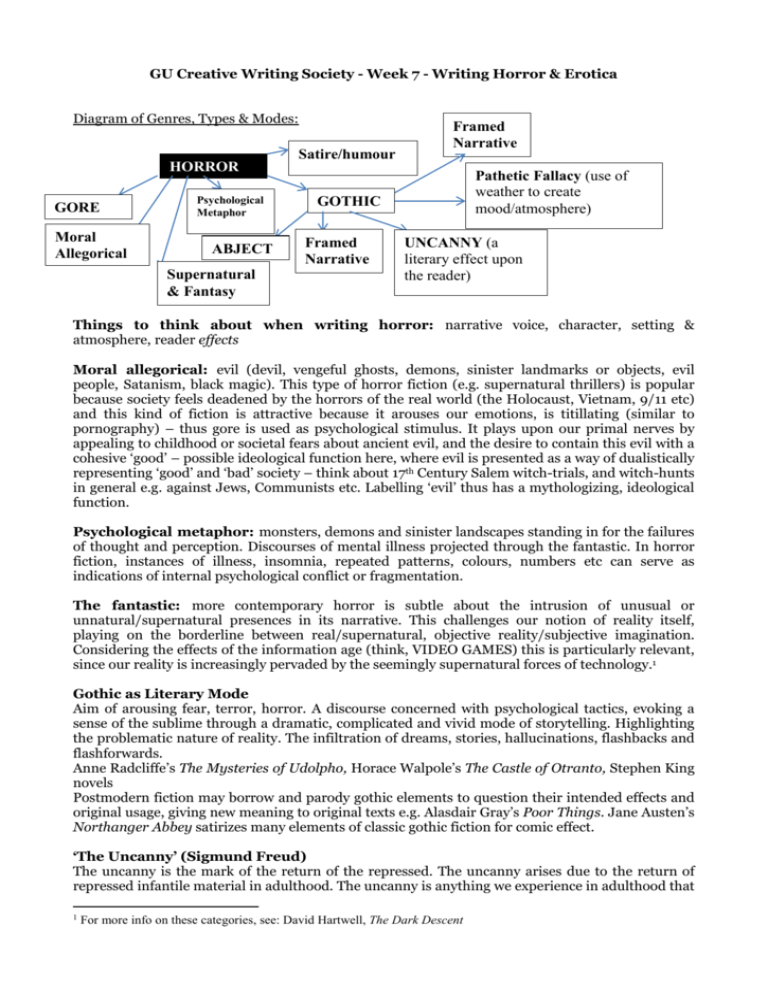

GU Creative Writing Society - Week 7 - Writing Horror & Erotica Diagram of Genres, Types & Modes: Satire/humour Framed Narrative HORROR GORE Moral Allegorical Psychological Metaphor ABJECT Supernatural & Fantasy Pathetic Fallacy (use of weather to create mood/atmosphere) GOTHIC Framed Narrative UNCANNY (a literary effect upon the reader) Things to think about when writing horror: narrative voice, character, setting & atmosphere, reader effects Moral allegorical: evil (devil, vengeful ghosts, demons, sinister landmarks or objects, evil people, Satanism, black magic). This type of horror fiction (e.g. supernatural thrillers) is popular because society feels deadened by the horrors of the real world (the Holocaust, Vietnam, 9/11 etc) and this kind of fiction is attractive because it arouses our emotions, is titillating (similar to pornography) – thus gore is used as psychological stimulus. It plays upon our primal nerves by appealing to childhood or societal fears about ancient evil, and the desire to contain this evil with a cohesive ‘good’ – possible ideological function here, where evil is presented as a way of dualistically representing ‘good’ and ‘bad’ society – think about 17th Century Salem witch-trials, and witch-hunts in general e.g. against Jews, Communists etc. Labelling ‘evil’ thus has a mythologizing, ideological function. Psychological metaphor: monsters, demons and sinister landscapes standing in for the failures of thought and perception. Discourses of mental illness projected through the fantastic. In horror fiction, instances of illness, insomnia, repeated patterns, colours, numbers etc can serve as indications of internal psychological conflict or fragmentation. The fantastic: more contemporary horror is subtle about the intrusion of unusual or unnatural/supernatural presences in its narrative. This challenges our notion of reality itself, playing on the borderline between real/supernatural, objective reality/subjective imagination. Considering the effects of the information age (think, VIDEO GAMES) this is particularly relevant, since our reality is increasingly pervaded by the seemingly supernatural forces of technology.1 Gothic as Literary Mode Aim of arousing fear, terror, horror. A discourse concerned with psychological tactics, evoking a sense of the sublime through a dramatic, complicated and vivid mode of storytelling. Highlighting the problematic nature of reality. The infiltration of dreams, stories, hallucinations, flashbacks and flashforwards. Anne Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho, Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, Stephen King novels Postmodern fiction may borrow and parody gothic elements to question their intended effects and original usage, giving new meaning to original texts e.g. Alasdair Gray’s Poor Things. Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey satirizes many elements of classic gothic fiction for comic effect. ‘The Uncanny’ (Sigmund Freud) The uncanny is the mark of the return of the repressed. The uncanny arises due to the return of repressed infantile material in adulthood. The uncanny is anything we experience in adulthood that 1 For more info on these categories, see: David Hartwell, The Dark Descent reminds us of earlier psychic stages, of aspects of our unconscious life, or of the primitive experience of human beings. It is a reminder of our psychic past. ‘The uncanny has to do with a sense of strangeness, mystery or eeriness. More particularly it concerns a sense of unfamiliarity which appears at the heart of the very familiar, or else a sense of familiarity which appears at the very heart of the unfamiliar’ (Bennett and Royle 2004: 34) Examples of the uncanny: Examples: deja vu, the mergence of the literary and the real, when something in real life takes on a fictional quality, defamiliarisation (Russian formalism), making the familiar strange, Brecht’s ‘alienation effects’, destabilising our notions of the ‘real’, making things uncertain, challenging rationality and logic, repetition, the double or doppelgänger, odd coincidences, animism (inanimate life is given attributes of animal or spirit), anthropomorphism (the attribution of human characteristics or behaviour to a god, animal, or object e.g. The Tales of Beatrix Potter), automatism, radical uncertainty about sexual identity, fear of being buried alive, claustrophobia, becoming unexpectedly stuck, silence, telepathy (the idea that perhaps your thoughts are not your own), death (our own body becomes defamiliarised), the logic of duplicity. In literature, what makes something uncanny is when the narrative pretends to realism but then subtly disturbs the real of this familiar world (think of the telepathic moment in Jane Eyre); fairytales, for example, are not uncanny because we have already suspended our disbelief, enabling us to accept ghosts, monsters etc. ‘The Abject’ (Julia Kristeva) Abjection is our reaction (sense of horror, vomit, tears, draining of blood from the face) to a threatened breakdown in meaning caused by the loss of the distinction between subject and object or between self and other. Examples of the abject: Corpse: a traumatic reminder of our own materiality, our existence not as transcendent but physical, perishable beings Examples of abjection: religious abhorrences (e.g. of homosexuality), incest, human sacrifice, bodily waste, death, cannibalism, murder, decay, perversion (e.g. violent pornography, pedophilia), Kristeva gives an intriguing example of the skin on the top of milk, which reminds us of the thin membrane of skin that defines the limits and borders of the human body, of the fragility of this demarcation between inside and outside. ‘Abjection is a sickness at one’s own body, at the body beyond that “clean and proper” thing, the body of the subject. Abjection is the result of recognizing that the body is more than, in excess of, the “clean and proper”’ (Elizabeth Grosz). Pathetic Fallacy: Attributing human qualities to nature and weather, often for literary effects. Macbeth, Wuthering Heights. Framed Narrative: Russian doll/Chinese box narratives, frames contained within other frames rather than having an overarching omniscient narrator. Serves in adding elements of ambiguity, estranging the reader, questioning the nature of truth – Heart of Darkness, Wuthering Heights, Frankenstein, Jennifer Egan’s The Keep - an interesting example as it incorporates the uncanny effects of modern technology as well as the experience of being without technology (a place with no signal). What is it to be cut off from technology; is it a severance with part of our reality? Gothic literature often betrays an ontological anxiety about the nature of reality and existence. Monsters and Metaphors: embodying society’s big Other, rejected because it incorporates part of us but at the same time disturbs this sense of ourselves; as Bennett and Royle (2004: 231) put it: The monster is both natural and unnatural, a grotesque development of, an outgrowth from or in nature. And it is for this reason that the monster must be abhorred, rejected, abjected, excluded. But let’s be clear about this: the monster is excluded, abjected, not because it is entirely other but because it is at least in part identical with that by which it is excluded – with, in this case [the case of Frankenstein’s monster], the human. Perhaps this is what is so disturbing about films like Devil’s Due: they take something we consider ‘natural’, an inherent part of human nature, and render it disturbing, horrific, abject. The monster is a way of exploring societal taboos which keep the unclean/dangerous out of society. Can you think of more examples in film or literature of this occurring? Politics of Horror: Franco Moretti, in ‘The Dialectic of Fear’ argues that the emergence of modern horror in the late 19th century is a result of ‘the terror of a split society’. The monster displaces fear from society to the monster, and provides the solace of social cohesion against the monster. Gothic, Horror and the Queer: ‘queer’ can refer to ‘the open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning when the constituent elements of anyone’s gender, of anyone’s sexuality aren’t made (or can’t be made) to signify monolithically’ (Sedgwick 1994, 8). Monsters, in a sense, ‘queer’ our notion of the human, whose identity is seen as essentially attached to gender – especially monsters who straddle the borderline between human/monster (e.g. Frankenstein’s monster who is constructed partially of human parts). There is the problem of their sexuality, their ‘sex’, their metaphysical identity. They represent a fundamental ambiguity at the heart of what we think we know we are, since they often contain a mix of gender traits, a mix of human/monster/animal traits – this ontological and metaphysical undecidability constitutes the uncanny nature of monsters: they invoke the familiar but make it seem unfamiliar, they estrange us from the familiar. What is a man? What is a woman? What is sexuality? What, indeed, is a human? Exercises: 15-Minute Fan Fiction 1) Choose one of the following examples from film and literature. Write a scene, a poem, a short story, a flash fiction or even a play borrowing from the modes we have discussed (horror, gothic, erotica). Then take five minutes to discuss what you have written with a partner. Think about the themes, the effects you have evoked. How does it diverge from or relate to the original text? If you want to, swap what you’ve written and comment on your partner’s work. 2) In groups select three prompts and come up with a story or idea. You could sketch a diagram, draw a map, make lists, focus on a character’s relationship rather than specifically plot, think about the setting (it’s up to you!): diet, possession, failure, betrayal, tomb, execution, hunted, fury, obsession, dreams, masochism, alone, fire, bloody tears, consumed, secrets, buried, hidden, playful, broken light, murderous heart, poison, asphyxiation, apocalypse, curse, emo, childbirth (some of these prompts were taken from http://horrorwriting.org/page/2/).