THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNER

advertisement

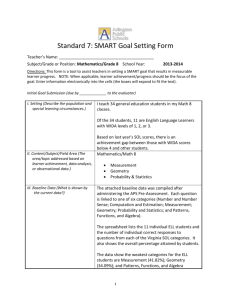

The English Language Learner 1 Running Head: THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE LEARNER This is a very well done study/paper. See the rubric for points lost. Several of your appendices should have been figures. I think that much of what you included in your methods data analysis section could actually have been presented in results. 99/100 The English Language Learner: Accommodations in a Local Mainstream Classroom University of West Florida The English Language Learner 2 Abstract The English language learner (ELL) is becoming a permanent part of the mainstream classroom. Language barriers, cultural diversity and educational needs of these students call for adaptations to materials and curricula. As the nation’s administrators develop programs and legislation to ensure the proper instruction of the ELL student the main accommodations are already in the classroom. This study surveys a sample population of a small district in Northwest Florida. Seven regular elementary teachers share how they modify their instruction and materials to accommodate the English language learners in their classrooms. Their adaptations will be compared to the best practice in their field. The English Language Learner 3 The English Language Learner: Accommodations in a Local Mainstream Classroom Introduction As of the 2000 Census, approximately 5% of the school population in Santa Rosa County, Florida consisted of English language learners (ELL). According to the National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition (NCELA), the Limited English Proficient (LEP) student population in Florida has grown more than 50% between 1995 and 2006. As this demographic grows so does the need to accommodate the second language learners. It is projected that in approximately forty years every classroom in the country will contain English language learners. In order for the local, mainstream teacher to include the non-native speaker in their native speaking setting they must be aware of the legislation involved and be prepared to educationally meet the needs of these students. Even though many educators work to accommodate the influx of culturally diverse students (Harklau, 1994) there are many who are skeptical about their efficacy when it comes to the ELL. (Medina-Jerez, W., et al., 2007, p.52) The need for accommodation and evaluation drives the study of how the average classroom teacher adjusts the classroom climate and programs to fit the learning needs of the English language learner. Further study is necessary on the topic and will be conducted at a local level. The proposed study will contribute a view of how mainstream classrooms integrate the non-English speaker with the English speaker. The research will draw from the public school The English Language Learner 4 system in the Northwest Florida region and will collect data about how the regular classroom teacher accommodates the student with limited English proficiency in comparison to their national counterparts. At a national level, the legislation set forth in the educational inclusion of the ELL consists of the No Child Left Behind Titles I and III. Each of these NCLB amendments dictated the requirements for assessing and accommodating the Limited English Proficient student. This included the legal expectations that each teacher instructing the ELL must be qualified. (NCES, 2002) Within the U.S., Florida is one of top six states that contain a large concentration of the Limited English Proficient population. (Capps, et.al, p.18) Florida’s Consent Decree is the State’s answer to this force. The Consent Decree helps Florida’s educational system remain in compliance with legislation related to the English language learner. The decree also sets forth the educational requirements of the teacher who will instruct the LEP students. (FLDOE) “That’s the law we go by”, was the simple statement shared by an interviewed participant. The district of Santa Rosa County in the Northwestern panhandle of Florida has very few English Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) enrolled in their school system. Currently there are approximately 120 students in the district’s 24 schools. (SRCSD) Despite this diminutive population within the region, there remains a great need to accommodate the LEP students and a necessity to educate the teachers who accommodate them. Research indicates that the English language learner not only brings a language barrier with them as they enter the mainstream classroom, but they also bring exceptionalities. Special needs in assessments and curricula pose challenges for the mainstream teacher. Some teachers have little or no experience with accommodating the ELL student and may fall short of effectively teaching the child. One participant admits, “Teachers are afraid because the child is The English Language Learner 5 different, the child does not talk, the child acts out because of resentment for being there, the teacher does not know when to help them, how far to help them, they are afraid because their test scores are going to be lower,..’How do I give a grade for this?’ ‘Do I pass them?” “Do I administratively place them? WHAT DO I DO?” (Lenski, et.al, 2006) Teachers throughout the nation need to have a strong knowledge base of the legislation, cultural diversity and the curricula adaptations that are associated with teaching the LEP student. Demands for accountability from the national and state level further drive teachers of ELL students to be skilled instructors. (Abella, 2005) According to a national study done by Borgum Yoon in 2007, the approach of teachers in the mainstream classroom set the tone and perception of the ELL students’ learning. Even if the LEP student is anxious or introverted, the accommodations and security that the teacher extends will either assist or hinder the child in the learning process. (Yoon, 2007) Much like students who are native speakers, the ELL student becomes proficient in an environment that encourages, accommodates and is sensitive to their needs. Accommodations noted in the reviewed educational sites and journals reveal the best practice for reaching the ELL student in the mainstream classroom consists of showing interest in the students’ culture, modeling and encouraging participation. (Yoon, 2007) Scaffolding, peer tutoring and one-on-one guidance are also mentioned as methods to help adapt the ELL to the classroom climate. (Palmer, et.al, 2006). With the understanding, gained from past research, that there is a national need to reach the second language student in a regular classroom setting; we focus in on a smaller facet of the educational realm. The Santa Rosa district of Florida is a small county (SRCSD) with an even smaller population of non English-speaking elementary students (SRCSD). This study will approach local teachers of the ELL in their regular classroom settings. Research through guided The English Language Learner 6 interviews and survey data will reveal the accommodations and teaching practices used in four Santa Rosa County elementary schools. What strategies do these teachers believe help accommodate the ELL? Are these methods comparable to their national counterparts and do use them in a manner that will teach the second language learner effectively? It is predicted that the teachers at the district level will be very similar in approach and practice to the mainstream teachers across the nation. The actual number of students may be the only differing factor when comparing the county to the country. The experience and education of each of the seven mainstream teachers will be taken into consideration and their aptitude to effectively teach the LEP student in a regular classroom setting will be investigated. Method Participants Participants for this study were selected from four Title I elementary schools in the district of Santa Rosa County, Florida. Seven mainstream teachers were selected based on current enrollment of English language learners in their classes. Grade levels taught by these regular classroom teachers range from kindergarten to second grade. Two kindergartens, four first grades and one second grade teacher all agreed to contribute their experiences and adaptations to the study. Once permission from the district superintendent was obtained, the researcher contacted the principles of five elementary schools in Milton, Pace and Bagdad. Four schools remain in the study due to the lack of English language learners in one of the targeted schools. Email was used to deliver the consent form, IRB draft and survey questions to each of the principals and later to each of the teachers. The researcher met with two principals and discussed the research and procedures outlined in the electronic documents that I had sent. After The English Language Learner 7 initial contact was made via email, with each of the teachers, the survey questions were sent out with instruction on how to complete and deliver the consent form, survey and interview times most convenient for them. Design Qualitative data was collected from each of the seven teachers in the form of an online survey, and a semi-structured interview. Convenience sampling was used in choosing the participants. The duplicated survey (Appendix A) consisted of nine questions in phase I that targeted responses on the teachers’ training, experience, their second language students and their instruction. Phase II of the survey asked each teacher to answer three open-ended questions pertaining to the adjustments that they made in their instruction and/or materials and how they would advise the novice teacher in reaching the second language student. The participants’ experience with the English language learner (ELL) varied from two years to ten years. Each of the seven, female, mainstream teachers was contacted separately to ensure anonymity within the study. After receiving online surveys from all participants involved, steps were taken to begin scheduling the semi-structured interviews. The interviews were scheduled with each teacher at the most convenient time for them during the day. Most preferred to meet within their planning times during the school day or after school. Dependent Variables or Measure This research sought to uncover the knowledge base of the elementary age ELL teacher in Santa Rosa County, FL and how it compares to similar teachers throughout the nation. The experience that participants had gained throughout their tenure and the training that they were required to have, upon their emergence into teaching the second language student, was the focus. The English Language Learner 8 How the teachers instruct the non-native speakers as well as the native speakers in their regular classroom was the measure. Questioning the teachers’ instructional manner and effectiveness with small group and individualized instruction was recorded. The instruction throughout the week in which the participant incorporated whole group, small group or personalized time with the ELL student was noted. The type and percentage of instruction indicated in the survey was translated to a bar graph for a visual interpretation. (Appendix B) Data collected in the semistructured interviews with each participant revealed their breadth of knowledge pertaining to state and district policies and requirements for teaching an ELL. The teachers’ articulation during the interview exposed how they felt about incorporating the second language student into their regular classroom setting, how they involved the student in the learning process and gave an overall view of their teaching approach. The instructional manipulations were accomplished by providing accommodations through actual delivery and materials used. Reliability Response rate was slower than expected for the survey and for scheduling the interview. This was attributed to the teachers’ scheduling and daily demands on their availability. Reaction to each question posed throughout the interview revealed the teachers true understanding of subject matter and policy. Duration and articulation of the teachers’ answers further displayed their approach to accommodating the ELL in their classroom. Nonverbal communication was also noted in the semi-structured interview. Consistency was maintained through query in the survey and the interview. The same questions were asked throughout each to support reliability. (Appendix C) Independent Variable The English Language Learner 9 Survey data revealed if teachers on a local level were emulating the requirements and strategies used by similar teachers throughout the nation. The adjustments by the participants, made to curricula and instruction, were collected and the accommodations of each participant were organized. The information disclosed through the semi-structured interviews proved that the variables used to manipulate instruction involved such accommodations as peer teaching, visual aids, picture pairings and individualized instruction. The ESOL specialist provides a list of suggested accommodations for each of the mainstream teachers. This guide provides best practice regular teachers can follow to bolster their own teaching efficacy. (Appendix D) Procedure and Data Collection Upon the decision to move forward with researching the education of the English language learner many articles were pulled from scholarly journals, census records and educational organization websites. After gleaning strategies and adjustments, statistics and facts about the growing population of the ELL student in the U.S. it was clear that a study on a local level was necessary. A research article was found which suited the focus of the planned study. This study was emulated once permission from the original investigators was obtained. After creating the required documentation to gain permission from the district school board progress was made to meet with the superintendent of schools in Santa Rosa County, FL. Santa Rosa County is a northwestern county in the panhandle area of Florida. Once authorization was obtained, elementary school principals from the towns of Milton, Pace and Bagdad were contacted. Milton and Pace schools had registered English language learners. These school principals replied with contacts within their faculty who would be likely to participate and who had experience teaching the ELL. The English Language Learner 10 All documentation was sent via email to the principals and the teachers. The IRB draft outlining the study, the consent form and the letter from the superintendent were all attached to the email sent to the faculty and administrators of each school. Further confirmation from each of the seven participants was received via a reply email. The replicated survey was reformatted into an online survey. This survey was sent separately to each participant. Individually, a link to the survey was sent out along with instructions for phase one, the multiple choice portion of the survey, and phase two, the open-ended questions on the survey. Each participant was asked to complete both phases and then check her schedule in order to set up a semi-structured interview time. The teachers’ rigorous schedule was taken into consideration and the interviews were planned at their convenience. Once all of the data was collected, from the survey and interviews, actions were taken to begin organizing and analyzing what had been gathered. Plan for Analysis of Data The method of data analysis used in this study was a qualitative research pattern. The environment of testing was a secure and natural setting. The sources of the information gathered were kept anonymous. According to Parsons and Brown (2002, p. 55), the most effective method of analyzing qualitative data is to group the data into like categories, explain the data, and then finally, decode the data. This process was followed. Pages of notes were dissected and categorized by independent variable. What percentage of the day the teacher was able to pull the ELL aside for some individualized instruction or if the teacher used peer teaching in lieu of teaching individual learners was another construct. One of the most scrutinized aspects of the data collection was how the teacher adjusted the delivery of her instruction to compensate for the communication barrier between herself and the ELL. Creation or alteration of curriculum materials, to fulfill the needs of the second language student, was also a type of data. The audio The English Language Learner 11 tapes were systematically categorized in this manner. Audio tapes were transcribed and then sorted in the aforementioned method. Tapes were listened to several times in order to ensure reliable transcription of data. Subsequent to the grouping of the data, the participants’ survey responses were added to the created categories. The interview segment brought to light the relationship between the teacher and the ELL students assigned to their mainstream classroom. One teacher incorporated her second language student’s background knowledge into a lesson plan on weather. He had previously lived in Missouri and had experienced a tornado. This teacher facilitated the instruction of her kindergarten class and centered on different students’ encounters with the weather. It allowed the English language learner to contribute to the group and truly share in the learning process with the other students. One participant revealed that the mainstream teacher must, “work on getting the student to feel comfortable with conversing within the classroom”. There were a couple of incidences when a non-native speaker displayed frustration or misbehaved, but this was viewed as more of a personality trait rather than an aversion to the classroom setting or schoolwork. This data will assist researchers and teachers with future study by providing a look at an area of the country that is just beginning to meet the needs of the English language learner in a regular classroom and how they are doing it The teachers in this area and in these schools are using what they have learned through training and coursework. Some felt that the training was ineffective as far as hands-on experience with the ELL and others stated, “Yes, it prepares you, but there is a lot of repetition and it is long”. They are animated, expressive and work hard to involve the second language student just as they would any other child with a special need. The environments that they create for the non-native in the classroom setting are print rich and adapting. All of the participants The English Language Learner 12 mentioned that they felt that is was important to make the non-native student comfortable in their classroom. One even went so far as to say that she wanted the classroom setting to be, “Homelike”. Two teachers mentioned, in the interviews, that they use a lot of English words side-by-side with Spanish words. They have also integrated pictures with the print in order to assist the ELL with understanding vocabulary. One teacher revealed that she felt that many of the methods and strategies she used with her native kindergarteners were also accommodations that enriched the learning process of her non-native kindergartener. Other than the usual classroom disruptions there were no outside interferences. Depending upon the ELL’s level of proficiency, each regular classroom teacher was assisted two or three days a week by a specialized English Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) instructor. The ESOL specialist conducts the assessments that are required for each English language learner according to guidelines set forth by Florida’s Consent Decree. This instructor would pull the English language learner from the mainstream classroom for thirty-minute blocks and instruct the child in a more individualized setting. As one of the few Santa Rosa County certified ESOL specialists, the woman interviewed revealed to me an outline of state standards that she adheres to when entering a student into the ESOL program. Once the new student has been assessed, by an oral examination, and the reading and writing too (for the third grade ELL) an initial ELL plan is drawn up. This ELL plan outlines the target areas for instruction and the objectives on how to achieve learning in these targeted areas. This particular ESOL specialist visits the regular classroom teacher and suggests accommodations that they can use in order to assist the ELL achieve their goals. In the interview, the thirty-year veteran educator shared some facts about reaching the ELL. Pertaining to accommodations she stated, “When you make The English Language Learner 13 accommodations you want them to learn the essentials”. She admitted, “It is work” when a regular classroom teacher takes on the second language student. This study is intended to loosely replicate a previous study on mainstream first grade teachers and their accommodations for the English language learners in their classrooms. In 2006, Drs. Clare Hite and Linda Evans investigated the understanding of accommodations for the ELL student in the mainstream classroom. These researchers pulled data from 22 mainstream, first grade teachers in a large Florida district. Their objective was to gain information on how these teachers understood the methods necessary to accommodate the second language learner in their classrooms. Results A grounded theory was used as the method to analyze the data. The data from the survey consisting of information on the instruction type, education and experience of the participant and the classroom arrangement was recorded in a database spreadsheet format. The semi-structured interviews were transcribed using a voice recorder and Microsoft word. After transcription was complete the researcher read the compiled data and categorized similar answers. Once the entire batch of data had been recorded in a spreadsheet, the researcher extracted similar terms or events. For example, one contributor revealed, “I pulled her a lot and spent a lot of one on one time with her” while another shared, “everyday, throughout the day, at least two times, when the other students were doing stations or independent work, I would create time with the ELL. Sometimes the assistant would work with ELL.” As in the replicated study (Hite, 2006) if there were ideas that stood apart from the norm they were absorbed into the major categories from the data. The major categories of The English Language Learner 14 accommodation, which surfaced, were curriculum modifications, instructional adaptations and teaching approach. Discussion What strategies do these teachers use to accommodate the ELL? Are these methods comparable to their national counterparts and are they exercised in a manner that will teach the second language learner effectively? Each participant, except one, indicated that they modified existing curricula to accommodate the ELL to some extent. One teacher stated, “Why reinvent the wheel?” as she explained that she would modify lesson plans and activities in order to adapt to the English language learners’ needs and levels of proficiency. Three of the seven participants shared Florida reading text and instruction guides that were geared towards the second language student. Yet another teacher stated that she used the same material with all of the students, nonEnglish speaking and English-speaking, but adjusted the instruction delivery when teaching her non-English speaking student. These accommodations are consistent to those found in research from other regions of the nation. The Hite/Evans study done in south Florida revealed that more than half of the teachers in their study altered their resources to be more helpful in teaching the ELL. It is a consensus that teachers need to alter their lessons and materials in order to help the second language student achieve. (Lenski, et.al, 2006). All participants in the study recognized that there is also a need to alter their instructional delivery. Six teachers, out of the seven surveyed, indicated that they use a lot of gestures, visual aids and repetition when instructing the ELL. Visual aids such as picture cards and word sorting were highly utilized in instruction modification. Participant number eight stated that she attempted to make all of her lessons “more visual and hands on”. Modeling was another important aspect to all participants. One teacher indicated that it was “very important to show The English Language Learner 15 the ELL student how to do things”. Several articles that also listed modeling as a top strategy in accommodating the ELL reinforced this. (Palmer, et.al, 2006; Yoon, 2007) Taking it slow and keeping instruction on a more basic level was an approach used by participant number seven in the study. She worked to help her second language learners develop basic classroom vocabulary in order for them to feel comfortable in expressing their needs. She shared, “We work on basic vocabulary that is necessary in the classroom like bathroom, colors, pencil, line-up, names etc. It is important to stay simple and not overwhelm the students.” As a kindergarten teacher this participant feels that the “child needs that foundation before growing academically.” This approach to practical instruction was also found in a study done on English language learners struggling to comprehend language in the classroom. A teacher in a Los Angeles school assisted a Central American student in understanding figurative language. In order to accomplish this, the teacher had to alter the instruction to exclude idioms or metaphors. The teacher also had to keep the dialogue in context and relate this content to real life situations. (Palmer et.al, 2006) Studies indicate that the inclusion of the ELL student in the regular classroom also requires the task of arranging more professional development for the teachers (Meltzer, 2006) or the difficulty of valid assessments. (Abella, 2005) This is not prevalent in the classrooms of Santa Rosa. Possibly, due to the few English language learners currently enrolled, mainstream teachers in Santa Rosa County seem to be supported by their administration. None of the seven participants seemed agitated or hurried when they sought to communicate with the ELL in their class. Each kindergarten teacher displayed effortlessness as they shifted their instruction from whole group to individual time with the second language student. One teacher revealed that she was glad that she was a kindergarten teacher. She felt that this helped her in her instruction and The English Language Learner 16 that the visual aids, manipulatives and the overall print rich environment of the classroom made it easier for her to accommodate help her ELL. A first grade teacher in the study reinforced research done on teaching the student “where they are” in their English proficiency. Much of the data proves significant in that it seemed to redirect the study at certain points. For example, several of the teachers held on to the philosophy that they would teach in the moment. In 2004, Dangling Fu noted that the regular classroom teacher should be concerned about helping the English language learner achieve, not simply regurgitate curriculum. This student achievement is demonstrated in many of the Santa Rosa classrooms. All of the participants stated that the most important aspect of their approach was to take things slow and be patient with the non-native speakers. The tone of the teachers’ delivery and the climate of the classroom influence how the ELL student understands the curriculum. The teacher must build the students’ confidence and trust. (Yoon, 2007) Peer teaching was another major category that emerged from the collected data. Five of the participants surveyed indicated that they utilized the more “responsible” students in their class to assist the English language learners in various activities and lessons. Two of the classroom teachers were fortunate enough to have two non-native speaking students in their class. In both cases, one of the second language learners was a bit more proficient in English and was able to model and translate for the ELL who was less able to comprehend. In her interview, one of the first grade teachers added that there were many instances that she felt that having a peer explain something to the non-native student helped them to relate to and understand it more clearly. “Children can learn and explain to each other much better than the researcher can.” Going a step farther, one study encouraged the peer support in order to involve the ELL in the The English Language Learner 17 classroom culture. This research stated that the English language learner performed at a higher level when they felt comfortable and accepted among their American peers. (Yoon, 2007) Upon data saturation it was discovered that a prevalent bit of advice emerged from one of the survey questions in the second phase. All participants in this study revealed that the training and education that they experienced was not as in depth as it should have been. The coursework and in service hours that were required for the teachers to house the ELL student in their classes did not provide them enough hands-on training and the skills to manipulate materials in order to adapt instruction for the second language learner. Most revealed that the coursework and in service hours were more situational in nature and provided little in the way of practice. Nationally, this is equally an issue in the education of the ELL educators. Many researchers express the need for a more immersed and specific program for teachers who instruct second language students. (Watson, et.al, 2005; Meltzer, 2006). There are several limitations to this study. Due to the variations in age, experience and education of the participants the sample population used should be taken into consideration. The results of this study should not be standardized. Furthermore, the region of the country and the low enrollment of the English language learner in Santa Rosa County schools is not a valid model for the rest of the country. Future research questions surfaced throughout this study. Are the English language learners well adjusted in their mainstream classroom? How are ELL students able to demonstrate what they know on English language achievement tests? Conclusion It was predicted that the teachers, at the district level, would be very similar in approach and practice to the mainstream teachers across the nation. Comparably, the participants in this The English Language Learner 18 study displayed an impressive amount of accommodating and adapting their instruction for the English language learner. Modeling, peer tutoring, individualized instruction and the use of visual aids are some of the strategies utilized throughout the nation. Research, at the local level, divulged that similar accommodations are used and instruction is modified to meet the ELL in Santa Rosa County. (Appendix E) These seven participants held their second language learners to high standards. They encouraged the same engagement and participation from the non-native and the native English speakers. In contrast, the mainstream teachers of Santa Rosa County showed little in the way of cultural recognition. Two educators revealed that they learned a few of words of the ELL’s native language. The ESOL specialist showed interest and cultural relativism as she shared a story about a student she had from a very primitive culture. These were the only indicators that the teachers in Santa Rosa County practice cultural relativism. Research found that this was a major factor in the adaptation of the ELL into a regular classroom setting. (Salinas, et.al, 2006) This is attributed to the fact that awareness of cultural diversity is more prevalent in other regions of the nation. The growth in the English language learner population is imminent. Although some regions of the nation will grow at a faster pace than others there is no doubt that each school system in the country will be influenced by the cultural shift. The needs of the students must be met and this means that accommodations must be made. The mainstream teacher at the classroom level will make these adjustments. The ELL success, in Santa Rosa County, is also highly dependent up on state budget cuts and a support of the ESOL program. According to the ESOL specialist, Santa Rosa County is geographically vast and difficult to cover. There is strong need for more ESOL specialists to meet the increase in the county’s ELL. This study is only a small sample of a population not yet fully influenced by the ELL growth. The future The English Language Learner 19 holds more ELL students for the District of Santa Rosa County, Florida and the data shown here will be a valuable foundation for future mainstream teachers accommodating the English language learner. References Abella, R., Urrutia, J., Shneyderman, A. (2005). An examination of the validity of Englishlanguage achievement test scores in an English language learner population. Bilingual Research Journal, 29(1), 127-144,229,233-234. Retrieved October 26, 2008, from Research Library database. (Document ID: 914801411). Capps, R., Fix, M., Murray, J., Ost, J., Passel, J., Herwantoro, S. (n.d.). The new demography of schools: Immigration and the No Child Left Behind Act. Retrieved November 22, 2008, from Research Library database. (Document ID: ED490924) Colorado State University. Writing Guides Concept Analysis. Retrieved November 6, 2009, from http://writing.colostate.edu/guides/research/content/com2b1.cfm Cowley, G. (2002, July). Santa Rosa school district 2000-2001 ESOL annual report: District self assessment. Retrieved September 29, 2008, available from the Santa Rosa County School Board http://www.santarosa.k12.fl.us The English Language Learner 20 Florida Department of Education. (n.d.). Retrieved October 17, 2008 from: www.fldoe.org/aala/cdpage2.asp http://www.fldoe.org/aala/cdpage2.asp Fu, D. (May 2004). Teaching ELL students in regular classrooms at the secondary level. Voices from the Middle, 4(11). Haager, D., Calhoon, M., Linan-Thompson, S. (2007). English language learners and response to intervention: Introduction to special issue. Learning Disability Quarterly, 30(3), 151152. Retrieved October 26, 2008, from ProQuest Psychology Journals database. (Document ID: 1323023001). Harklau, Linda. (1994). ESL versus mainstream classes: contrasting L2 learning environments TESOL Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 2 pp. 241-272. Hayes, K. & Salazar, J. J. "Final Report: Year I." Evaluation of the structured English immersion program. Los Angeles Unified School District, CA, March 12, 2001. 80 p. Hite, C.E, Evans, L.E.. (2006). Mainstream first-grade teachers’ understanding of strategies for accommodation the needs of English language learners. Teacher Education Quarterly, 33(2), 89-110. Retrieved October 16, 2008, from ProQuest Education Journals database. (Document ID: 1034273091). Lenski, S. D., Ehlers-Zavala, F., Daniel, M C, & Sun-Irminger, X. (Sept 2006). Assessing English-language learners in mainstream classrooms. The Reading Teacher, 60, 1. p.24 (11). Retrieved October 16, 2008, from Academic OneFile via Gale: http://find.galegroup.com.ezproxy.lib.uwf.edu/itx/start.do?prodId=AONE Medina-Jerez, W., Clark, D.B., Medina, A., Ramirez-Marin, F. (2007). Science for ELLs: The English Language Learner 21 Rethinking our approach. The Science Teacher, 74(3), 52-56. Retrieved October14, 2008, from Research Library database. (Document ID: 1230210251). Meltzer, J, Hamann, E.T. (2006). Double-duty literacy training. Principal Leadership, 6(6), 2227. Retrieved October 13, 2008, from Research Library database. (Document ID: 991115501). National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.). Retrieved September 18, 2008, from http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/# United States Census Bureau. (2006). State and county quick facts: Florida. Retrieved October 13, 2008, from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/12/12113.html Palmer, B.C., Shackelford, V.S., Miller, S.C., Leclere, J.T. (2006). Bridging two worlds: Reading comprehension, figurative language instruction, and the English-language learner. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 50(4), 258-267. Retrieved October 26, 2008, from Research Library database. (Document ID: 1178651571). Parsons, R. D. & Brown, K. S. (2002). Qualitative and quantitative methodology. In D. Alpert, Ed. Teacher as reflective practitioner and action researcher (pp. 54-58). Belmont, CA. Wadsworth Group. Purdy, J. (2008). Inviting conversation: meaningful talk about texts for English language learners. Literacy, 42, 1., pp. 44-51. Retrieved October 11, 2008, from MetaLib database http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=1442924391& Fmt=2& VInst=PROD& VType=PQD& RQT=309& VName=PQD& The English Language Learner 22 Reed, B., Railsback, J. (2003, May) Strategies and resources for the mainstream teachers of English language learners. Retrieved September 29, 2008, from http://www.nwrel.org/request/2003may/ Salinas, C., Franquiz, M. & Guberman, S. (2006). Introducing historical thinking to second language learners: Exploring what students know and what they want to know. The Social Studies, 203-207. United States Department of Education. (n.d.). Title III- Language instruction for limited English proficient and immigrant students. Retrieved October 13, 2008, from http://www.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/esea02/pg39.html Watson, S., Miller, T. L., Driver, J., Rutledge, V. & McAlliste, D. (2005). English language learner representation in teacher education textbooks: A null curriculum? Education, 1(126), 148-157. Yoon, B. (2007). Offering or limiting opportunities: Teachers' roles and approaches to Englishlanguage learners' participation in literacy activities. The Reading Teacher, 3(61), 216225. The English Language Learner Appendix A 23 The English Language Learner Appendix B 24 The English Language Learner Appendix C 25 The English Language Learner Semi-Structured Interview Questions How do you involve a student who is a native speaker in the learning process? Describe your teaching approach. Describe your curriculum modifications Describe your instructional adaptations How do you feel about peer teaching? What do you know about the Consent Decree in Florida? Did the training/education that you acquired prepare you for teaching the ELL? What type of instruction does your ELL student receive from the ESOL specialist? Do you have any preferred resources that you use on a regular basis? What advice would you give to an incoming teacher who will be teaching the ELL in their mainstream classroom? Appendix D 26 The English Language Learner Appendix E 27 The English Language Learner Percentage of Accommodations Used Comprehension Strategies 15% Instruction Delivery 22% Visual Aids 37% Language Proficiency Based Adaptations 26% 28