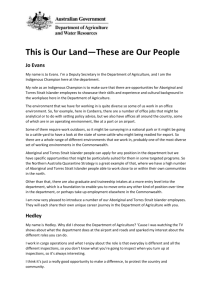

RightsEd: Australia as a nation – race, rights and immigration

advertisement