eindversie - Universiteit Leiden

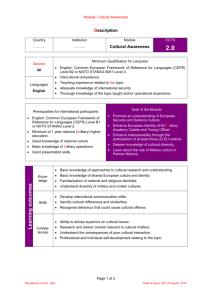

advertisement