Single Unit Transfusion Guideline – Supporting Material

Appendix 2: Implementation Guide

Implementation Guide

Single Unit Transfusion Guideline – Supporting Material

Supporting material for key champions within hospitals to present to relevant hospital governance committees seeking agreement to the guideline and its implementation

Key Champions

Director Medical Service/Clinical Operations, Director of Nursing, Directors Clinical Governance, Patient

Safety/Quality Managers, Blood Management Medical and Nursing staff

Consider senior medical clinicians from: Haematology, Anaesthetics, Surgery, Renal, Oncology, Intensive care, Paediatrics.

Chair of Transfusion Governance Committee / Patient Blood Management Committee

Hospital Governance committees

Clinical Governance, Policy and Procedure directors, CEO’s, Hospital Boards / Directors / Executive,

Quality Systems management

OUTLINE:

1.

Overview of the Single Unit Guideline

2.

Reason for implementation

3.

Implementation Plan

4.

Resources required

5.

Plan for monitoring and tracking compliance / success

6.

Examples of promotional material

7.

Other successful Programs

8.

Supporting Evidence from Literature

1. Overview of the Single Unit Transfusion Guideline

This Guideline is adapted from the Single Unit Transfusion Guideline developed by the National Blood

Authority, Australia.

1 It is intended for use by all clinicians responsible for prescribing blood transfusion to stable normovolaemic patients who are not actively bleeding and not in an operating theatre.

In line with the Patient Blood Management Guidelines: “Where indicated, transfusion of a single unit of

RBC, followed by clinical reassessment to determine the need for further transfusion, is appropriate. This

reassessment will also guide the decision on whether to retest the Hb level”.

2,3 Ensure haemoglobin levels are aligned with the Patient Blood Management Guidelines.

2–4

If the patient is symptomatic, and Hb is consistent with the Patient Blood Management Guidelines, then transfuse 1 unit, and reassess patient for clinical symptoms of anaemia before transfusing further units.

Minimise risks of transfusion by restricting the number of units where possible, as evidence suggests transfusion risks are dose dependant.

5,6

Practice evidence based transfusion, by assessing the patient and symptoms, together with haemoglobin, rather than transfusion based on habit, or tradition.

2. Reason for Implementation a.

Current practice does not always align with the current evidenced-based guidance.

1–4 b.

The Patient Blood Management Guidelines (Module 2 - Perioperative; Module 3 - Medical and Module 4 - Critical Care) 2–4 support restrictive transfusion and a single unit strategy. c.

The National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards (Standard 7: Blood and Blood

Products) require blood and blood product policies and procedures to be consistent with national evidence based guidelines for pre-transfusion practices, prescribing and clinical use of blood and blood products.

7 http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wpcontent/uploads/2012/10/Standard7_Oct_2012_WEB.pdf

i.

7.1.1 Blood & blood product policies, procedures and/or protocols are consistent

with national evidence-based guidelines for pre-transfusion practices, prescribing

& clinical use of blood & blood products ii.

7.1.3 Action is taken to increase the safety & appropriateness of prescribing & clinically using blood & blood products iii.

7.2.2 Action is taken to reduce the risks associated with transfusion practices & the clinical use of blood and blood products iv.

7.4.1 Quality improvement activities are undertaken to reduce the risks of patient harm from transfusion practices & the clinical use of blood & blood products d.

Single unit transfusions are safe in stable, normovolaemic patients who are not actively bleeding and not in an operating theatre and reduce transfusion associated morbidity and mortality.

8,9 e.

If one unit has achieved the stated outcome for the transfusion, for example improvement in haemoglobin or symptoms, further units will only increase the risks without adding benefit.

5,6

National Blood Authority pg. 2

f.

Transfusion is a live tissue transplant. Risks associated with transfusion are dose dependent.

10,11 g.

A two unit transfusion increases the risk of nosocomial infection and other long term morbidities.

10,11 h.

Transfusion Associated Circulatory Overload (TACO) is among the high risks, estimated at 1 in 100 per unit transfused.

2–4,12,13 i.

Historically, two unit red blood cell transfusions were normal practice. Single unit transfusions remain only a small proportion of all transfusion. j.

In addition to exposing patients to increased risk without commensurate benefit to patient outcome, red blood cell transfusion also poses on-going challenges in balancing supply and demand due to the increasing age of the population: demand for blood will increase but the available donor pool will decrease. Although blood is extremely safe from the currently known infectious agents, the potential threat from as yet unknown, or re-emerging pathogens deserves cautious consideration.

5 k.

Patient blood management is encouraged by World Health Organisation, through World

Health Assembly. Safe and rational use of blood, patient blood management.

14 l.

Reasons modern health systems need to shift from product-focused transfusion practice to patient blood management.

5 v.

Patient blood management has been shown to be a more effective concept than

“appropriate use” in pre-empting the need for blood components, reducing overall use, and improving patient outcomes. vi.

The ageing population – increased demand for blood products, and a reduced donor pool available. vii.

Increasing pressure on the cost of blood transfusion – many different costs in provision from collection to transfusion – real cost is a multiple of the actual product cost. viii.

Threat from known, new or re-emerging pathogens while facing uncertainty over their potentially long silent carrier states. ix.

Emerging evidence that transfusion is an independent risk factor for adverse outcomes including increased morbidity, mortality and hospital length of stay.

6 x.

A lack of evidence for the benefit of transfusion. m.

The Single Unit Transfusion Guideline and patient blood management will align with State

Governments’ Health Service Strategic Plans, and Hospital organisational values and mission statements. n.

Queensland, Victoria, NSW and SA Health Departments have strategic plans that have elements aligning with PBM principles. They variously mention health services focused on the patient, providing value, innovation, quality initiatives, and response to the aging population. (Western Australia already has full patient blood management program in place.) This is true also of individual hospitals and hospital groups.

National Blood Authority pg. 3

o.

The Single Unit Transfusion Guideline has potential to reduce red blood cell utilisation and preserve the blood supply.

15,16

3. Implementation Plan a.

Gain approval from executive management, medical director (or equivalent) for hospital or health group. Involve hospital quality managers, Transfusion Governance Committee and

Clinical Governance / Patient blood Management Committee where possible. b.

Identify and recruit champions from medical staff to assist in promotion and implementation of the Single Unit Transfusion Guideline. c.

Identify staff for education and promotional roles, and/or utilise transfusion nurse specialists, hospital educators or equivalent if available. d.

Utilise existing Transfusion Governance Committee to promote patient blood management and the Single Unit Transfusion Guideline through this group. Introduce patient blood management into Terms of Reference, local literature, and single unit transfusion into all hospital policies and procedures around transfusion practices. e.

Education should ensure clarification that single-unit rule does not apply to patients in theatre, the chronically transfused or for actively bleeding patients. If not already available, create a Massive Transfusion Protocol .

17 f.

Educate medical staff also on the material provided to patients, and the questions patients will be encouraged to ask. Ensure awareness of real risks of transfusion. g.

If available, modify computerised physician order entry (CPOE) software to guide decision to transfuse, and prescription of red cells to ensure compliance with the Single Unit

Transfusion guideline. (Create distinction between “actively bleeding? – Yes or NO” If No, only allow order for 1 unit at a time, with explanations required for over-rides.) h.

Hospital wide education to all staff: Use catch-phrase : “Be Single minded” i.

Grand Rounds, Morbidity and Mortality (M&M) meetings, Division/specialty regular meetings or seminars ii.

Intranet and website features, internal magazines, regular internal publications including electronic communications. Cycle eye-catching and variable promotional material, repeat exposure regularly. iii.

Laboratory staff meetings, education seminars, notice boards iv.

Display boards in medical specialty areas, staff rooms, conference rooms v.

Information incorporated into orientation education for medical, nursing and laboratory staff. vi.

Information provided with every red blood cell issue from Laboratory for introductory period. (Printed on release report if possible with IT system in use, or leaflets.) vii.

Training manuals in laboratories to reflect patient blood management principles and single-unit transfusion guideline information.

National Blood Authority pg. 4

i.

Patient / consumer education material available for pre-operative clinics, medical clinics, outpatient areas, emergency rooms, treatment rooms, and on public access websites. j.

Empower transfusion laboratory and nursing staff to monitor compliance to the Single Unit

Transfusion Guideline. i.

Provide copy of the guideline, and scripts of questions to assess prescription or request is compliant to policy, and provide a mechanism to document requests and challenges. ii.

Ensure appropriate medical staff (haematology, clinician Champion) are available to support challenges to requests. iii.

Provide easy access to educational material that the laboratory or nursing staff can share with prescribers, if necessary.

4. Resources Required a.

Clinical Champions b.

Nominated staff to provide education, promotion, monitoring and data collection. c.

Printed promotional material; posters, leaflets, brochures d.

Electronic promotional material – IT support for access to local systems e.

Ability to modify existing Electronic Ordering software if available

5. Plan for monitoring and tracking compliance / success a.

Collect data to monitor compliance to policy and provide feedback to Hospital Executive /

Quality Managers, Transfusion Governance Committee / Patient Blood Management

Committee, Medical Specialties/ Divisions, Educators, Laboratory managers and senior staff. b.

Data may include: i.

A log of requests submitted that do not fall within the policy criteria. ii.

The number of red blood cell units ordered into inventory daily. (BloodNet statistics.) iii.

The number of units transfused per patient. iv.

The number of patients who received a single unit transfusion per day. v.

Audits of patient medical records, of transfusion episodes assessing compliance to the Single Unit Transfusion Guideline. c.

Provide feedback: i.

Introduce this data collection and analysis as a standing item on the Transfusion

Governance Committee / Patient Blood Management Committee agenda ii.

Report results to wards and divisions regularly, and to quality managers

National Blood Authority pg. 5

iii.

Share statistics with transfusion staff to highlight the impact of the introduction of the single unit policy iv.

Provide a forum for problems or difficulties to be aired, discussed and resolved v.

Provide access to further information regarding the Single Unit Transfusion

Guideline, restrictive transfusion practice and patient blood management. d.

Benchmark data within local wards and divisions, and between health facility groups and clusters, and with external facilities. Benchmark within states and territories, and Nationally. e.

This activity will demonstrate compliance with National Health and Safety in Health Care

Standard 7: Blood and Blood Products: 7

7.1.2 The use of policies, procedures and/or protocols is regularly monitored.

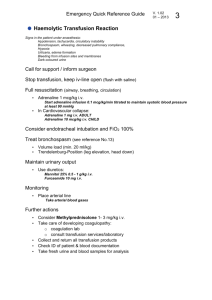

6. Examples of promotional material – see supporting material a.

Posters b.

PowerPoint Presentations

7. Other Successful Programs

The Western Australian Government implemented the Patient Blood Management Project, with a single unit transfusion “rule” in 2011.

18

New Zealand – Auckland District Health Board 19 In 2010 introduced PBM and single-unit transfusion policy.

Toronto, Canada 20 - In 1998, St. Michael’s Hospital became one of the first in Canada to implement a blood conservation program. The Ontario Transfusion Coordinators (ONTraC) program administered through St. Michael’s sets the standard in the province for patient blood management.

USA – Eastern Maine Medical Centre, Bangor.

21

Europe: 22 Austria, Switzerland: PBM strategies established in only a few hospitals.

Netherlands – PBM for ten years.

National Blood Authority pg. 6

8. Supporting Evidence from Literature

Clinical Trials:

TRICC A Multicenter, Randomised, Controlled Clinical Trial of Transfusion Requirements in

Critical Care. Herbert PC, Wells G et al. N Engl J Med 1999;340 (6):409-17 16

838 stable, critically ill patients. Hb < 9g/dL within 72 hrs of ICU admission

Randomised to o restrictive (Transfuse if Hb falls below 7g/dL) or o liberal(Transfuse if Hb falls below 10 g/dL)

Conclusions: “Overall, 30-day mortality was similar in the two groups…However, the rates were significantly lower with the restrictive transfusion strategy among patients who were less acutely ill…but not among patients with clinically significant cardiac disease…The mortality rate during hospitalisation was significantly lower in the restrictive-strategy group..”

“A restrictive strategy of red-cell transfusion is at least as effective as and possibly superior to a liberal transfusion strategy in critically ill patients, with the possible exception of patients with acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina.”

TRACS -Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: the TRACS randomised controlled trial. Hajjar

LA, Vincent JL et al. 2010 JAMA 2010;304:1559-67.

11

Single Centre, prospective, noninferiority randomised controlled trial.

502 adults needing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass

Transfusion thresholds o Liberal Hct ≥ 30% o Restrictive Hct ≥ 24%

Conclusions: “Among patients undergoing cardiac surgery, the use of a restrictive perioperative transfusion strategy compared with a more liberal strategy resulted in noninferior rates of the combined outcome of 30-day all-cause mortality and severe morbidity.”

FOCUS: Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. Carson JL et al. N Engl J

Med 2011;365(26):2453-62.

23

Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery.

2016 patients, 50 years of age or older

History or risk factors for cardiovascular disease

Haemoglobin level < 10 g/dL after hip-fracture surgery.

Transfusion thresholds: o Liberal – Hb 10g/dL o Restrictive – symptoms of anaemia or Hb< 8g/dL

Conclusions: “A liberal transfusion strategy, as compared with a restrictive strategy, did not reduce rates of death or inability to walk independently on 60-day follow-up or reduce in-hospital morbidity in elderly patients at high cardiovascular risk.”

National Blood Authority pg. 7

Transfusion thresholds and other strategies for guiding allogeneic red blood cell transfusion –

Cochrane Review. Carson JL et al. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012: Issue 4 9

19 RCT (6264 patients, excludes neonates)

Patients randomised to intervention or control group+

Intervention based on clear transfusion trigger – haemoglobin or haematocrit

Clinical settings: o 10 surgery (cardiac, vascular, vascular or orthopaedic) o 5 acute blood loss and/or trauma o 3 critical care units o 1 BMT patients undergoing chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation. o No trials in patients with acute coronary syndrome

Conclusions: Restrictive transfusion strategies

Reduced the risk of receiving a RBC transfusion by 39% (risk ratio (RR) of 0.61 and average absolute risk reduction (ARR) of 34%

Reduced the volume of RBCs – on average by 1.19 units

Did not appear to impact the rate of adverse events compared to liberal strategies (i.e. mortality, cardiac events, myocardial infarction, stroke, pneumonia and thromboembolism)

Were associated with a statistically significant reduction in hospital mortality

(RR 0.77) but not 30-day mortality (RR 0.85).

Did not reduce functional recovery, hospital or intensive care length of stay.

Appropriateness of allogeneic red blood cell transfusion: the international consensus conference on

transfusion outcomes. Shander A, et al. Transfus Med Rev. 2011 Jul;25(3):232-246.e53 (15

Collaborators).

24

An international multidisciplinary panel of 15 experts reviewed 494 published articles and used the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method to determine the appropriateness of allogeneic red blood cell (RBC) transfusion based on its expected impact on outcomes of stable nonbleeding patients in 450 typical inpatient medical, surgical or trauma scenarios. o RBC transfusion rated as appropriate in 53 (11.8%) scenarios

81% of these Hb 7.9 g/dL or less, associated comorbidities, age older than 65 years. o RBC transfusion rated as inappropriate in 267 (59.3%) scenarios

All scenarios of patients with Hb 10 g/dL or higher and in 71.3% of scenarios with patient Hb 8 to 9.9 g/dL.

No scenario with patient’s Hb level of 8 g/dL or more was rated as appropriate o RBC transfusion rated as uncertain appropriateness in 130 (28.9%).

Strategies to pre-empt and reduce the use of blood products: an Australian perspective. Hofmann, A et al. (2012). Curr Opin Anesthesiol , 25:66-73.

6

National Blood Authority pg. 8

There is also accumulating evidence for a dose dependent relationship between transfusion and adverse outcome [45,47,49,52]. The overall conclusion is that there is a paucity of evidence for benefit but a burgeoning literature demonstrating a strong association between transfusion and adverse outcomes.

Conclusions: …many patients receive blood components unnecessarily. The accumulating evidence for adverse transfusion outcome warrants a precautionary approach and calls for a paradigm shift towards PBM. The concept of PBM is superior

to that of appropriate use because it strategically pre-empts and reduces transfusions by addressing modifiable risk factors that may result in transfusion long before a transfusion may even be considered, and it improves patient outcomes whilst reducing

cost.

A new perspective on best transfusion practices Shander A, et al.Review. Blood Transfus DOI

1032450/2012.0195-12.

25

Conclusion: Considered for decades as a gift of life, blood transfusion is emerging as a treatment with limited efficacy and substantial risks, further under pressure from staggering associated costs and limited supplies.

Better transfusion practice should not be viewed as an option, but a necessity to ensure clinicians are giving benefit and not doing harm to their patients.

Is single-unit blood transfusion bad post-coronary artery bypass surgery? Warwick R. et al. Interact

Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2013 Jun;16(6):765-71.

26

We investigated the effects of a single-unit blood transfusion on long-term survival post-cardiac surgery in isolated coronary artery bypass grafting patients

Conclusions: Cox regression and propensity matching both indicate that a single-unit

transfusion is not a significant cause of reduced long-term survival. Perioperative anaemia is a significant confounding factor…..we are not advocating liberal transfusion and would

recommend changing from a double-unit to a single-unit transfusion policy. We speculate blood is not bad, but that the underlying reason that it is given might be.

Blood transfusion in cardiac surgery is a risk factor for increased hospital length of stay in adult

patients. Galas F et al. Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery 2013, 8:54.

27

The primary objective…was to assess the relationship between RBC transfusion and hospital length of stay (LOS), in a large, single reference centre of cardiac surgery.

Secondary objectives were to compare the characteristics of patients who received RBC transfusion with those who did not, to evaluate the relationship of the number of transfused RBC units with mortality and clinical complications, and to identify the predictive factors for a prolonged hospital LOS.

Conclusions: The increased length of hospital stay related to the number of transfused RBC units supports restrictive therapy in cardiac surgery. In addition…clinicians should

National Blood Authority pg. 9

administer only 1 RBC unit at a time, because this may result in less exposure to risks but similar benefits. Importantly……our results brings additional information regarding an independent association of early RBC transfusion with longer hospital stay.

Transfusion Strategies for Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Villanueva C et al.N Engl J Med 2013

Jan;368;1:11-21 28

Conclusions: As compared with a liberal transfusion strategy, a restrictive strategy significantly improved outcomes in patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

The British Committee for Standards in Haematology (BCSH) Guidelines on the Administration of Blood

Components. Addendum to Administration of Blood Components, August 2012 8

August 2012 released an addendum to Guidelines on the administration of blood components.

There is a specific reference to single-unit transfusions as a means to minimise the incidence of transfusion associated circulatory overload (TACO).

Currently, TACO is estimated to occur at a rate of up to 1 in 100 transfusions, per unit

transfused, and is considered high risk.

National Blood Authority pg. 10

REFERENCES:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

National Blood Authority Single Unit Transfusion Guideline (Currently in Development). (2013).

National Blood Authority Patient blood management guidelines: Module 3 – Medical. (National

Blood Authority: Canberra, Australia, 2012).at <http://www.blood.gov.au/pbm-guidelines>

National Blood Authority Patient blood management guidelines: Module 4 – Critical Care.

(Canberra, Australia, 2013).at <http://www.blood.gov.au/pbm-guidelines>

National Blood Authority Patient blood management guidelines: Module 2 – Perioperative.

(Canberra, Australia, 2012).at <http://www.blood.gov.au/pbm-guidelines >

Hofmann, A., Farmer, S. & Shander, A. Five drivers shifting the paradigm from product-focused transfusion practice to patient blood management. The oncologist 16 Suppl 3, 3–11 (2011).

Hofmann, A., Farmer, S. & Towler, S. C. Strategies to preempt and reduce the use of blood products: an Australian perspective. Current opinion in anaesthesiology 25, 66–73 (2012).

7.

8.

9.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare Safety and Quality Improvement

Guide Standard 7: Blood and Blood Products. ACSQHC (2012).at

<http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wpcontent/uploads/2012/10/Standard7_Oct_2012_WEB.pdf>

The British Committee for Standards in Haematology Guidelines on the Administration of Blood

Components. Addendum to Administration of Blood Components, August 2012. 1–4 (2012).at

<http://www.bcshguidelines.com/documents/BCSH_Blood_Admin_-

_addendum_August_2012.pdf >

Carson, J. L., Carless, P. a & Hebert, P. C. Transfusion thresholds and other strategies for guiding allogeneic red blood cell transfusion. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 4, CD002042

(2012).

10. Koch CG Duncan AI et al, L. L. Morbidity and mortality risk associated with red blood cell and blood-component transfusion in isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Crit Care Med 2006 34,

1608–1616 (2006).

11. Hajjar LA Vincent JL et al. Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: the TRACS randomised controlled trial. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 304, 304:1559–1567

12. Roback, J. D. Non-infectious complications of blood transfusion. AABB AABB Techn, (2011).

13. Popovsky, M. Transfusion-associated circulatory overload. ISBT Science Series 166–169 (2008).

14. World Health Organisation Availability, safety and quality of blood products WHA63.12. 1–4

(2010).at <http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA63/A63_R12-en.pdf>

15. Berger, M. D. et al. Significant reduction of red blood cell transfusion requirements by changing from a double-unit to a single-unit transfusion policy in patients receiving intensive chemotherapy or stem cell transplantation. 97, 116–122 (2012).

National Blood Authority pg. 11

16. Hébert, P. C. et al. A multicenter , randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. N Engl J Med 340, 409–417 (1999).

17. National Blood Authority Patient Blood Management Guidelines: Module 1 - Critical Bleeding /

Massive Transfusion. (Canberra, Australia, 2011).at <http://www.blood.gov.au/pbm-guidelines>

18. Western Australia Government Single Unit Rule: A Quick Start Guide to Transfusion Reduction.

(2012).at <http://www.health.wa.gov.au/bloodmanagement/docs/Single Unit Rule.pdf>

19. Ombler, K. Blood is a Gift. Project of Auckland District Health Board Transfusion Committee.

Public Sector 36:1, (2013).

20. Shepherd, L. St. Michael’s to create centre for patient blood management. St Michael’s Hospital,

Toronto Canada at

<http://www.stmichaelshospital.com/media/detail.php?source=hospital_news/2012/20120913a

_hn>

21. Eastern Maine Medical Center Patient Blood Management Program. (2007).at

<http://www.emmc.org/blood_management.aspx?id=36102>

22. Shander, A. et al. Patient blood management in Europe. 109, 55–68 (2012).

23. Carson, J. et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J

Med. Dec 29; 36, 2453–2462 (2011).

24. Shander A, Fink A, Javidroozi M, Erhard J, Farmer SL, Corwin H, Goodnough LT, Hofmann A,

Isbister J, Ozawa S, S. D. I. C. C. on T. O. G. Appropriateness of allogeneic red blood cell transfusion: the international consensus conference on transfusion outcomes. Transfus Med Rev.

Jul; 25, 232–246.e53 (2011).

25. Shander, A. A new perspective on best transfusion practices. Review Blood Transfus 1, (2012).

26. Warwick R, Mediratta N, Chalmers J, Pullan M, Shaw M, McShane J, P. M. Is single-unit blood transfusion bad post-coronary artery bypass surgery? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. Jun;16,

765–771 (2013).

27. Galas, F. R. et al. Blood transfusion in cardiac surgery is a risk factor for increased hospital length of stay in adult patients. Journal of cardiothoracic surgery 8, 54 (2013).

28. Villanueva, C. et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. The New

England journal of medicine 368, 11–21 (2013).

National Blood Authority pg. 12