Early and Late Outcomes in patients after heart transplant

advertisement

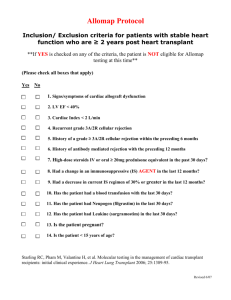

Early and Late Outcomes in patients after heart transplant The objectives of this lecture are as follows: 1) To learn predictors of mortality and other adverse outcomes in patients presenting for heart transplant 2) To discuss the early and long-term outcomes and complications in the patient after heart transplantation. 3) To review anesthetic concerns when these patients present for non-cardiac surgery following heart transplantation Pre-transplant donor and recipient risk factors associated with increased mortality post-transplant Older donor age Increased recipient weight and body mass index Higher rates of recipient diabetes mellitus and recipient nicotine use history Longer allograft ischemic time Higher proportion of recipients with panel-reactive antibody (PRA) > 10% Congenital heart disease Pre-transplant LVAD use Requirement of post-operative short term extracorporeal mechanical circulatory support Recipient on ventilator at time of transplant Recipient history of dialysis Female > Male Infection within 2 weeks of transplant treated with antibiotics Transplant volume at institution decreasing Compatible but non-identical ABO Prior transfusions Ischemic cardiomyopathy > non-ischemic cardiomyopathy Increasing pre-transplant serum creatinine, bilirubin and increasing pulmonary vascular resistance Increasing recipient age As patient survival progresses to 5 years, drug-treated rejection prior to first hospital discharge and rejection between discharge and first year become significantly associated with increasing mortality. Intra and post-operative vasoplegia 5-15% incidence Associated with longer ischemic times, donor recipient weight mismatch, platelet transfusion, VAD, TAH and acidosis Results in delayed extubation, more ECMO, more IABP use, increased incidence of open chest, prolonged ICU stay, increased morbidity and mortality Early graft failure Primary cause of 30 day mortality post OHT Occurs in 10% of patients with a 56% or greater mortality Multifactorial pathophysiology Possible link with redo operation, increased blood products, long ischemic time. Only modifiable risk factor is optimal D/R matching Reasons for improved early outcomes Improved organ transplantation Better tolerated immunosuppression and new agents Careful patient selection Multidisciplinary transplant centers with improved follow up Better early outcomes = more late allograft failure, coronary artery disease is the major cause of allograft loss after the first year post-transplant. Coronary artery disease post OHT (TCAD) 32% of patients at 5 years, 53% 10 years TCAD is characterized by an aggressive form of diffuse arterial narrowing Chronic allograft rejection usually presents as accelerated CAD Asymptomatic secondary to denervation of the heart should have periodic coronary angiography. Diffuse nature makes PCI mostly palliative Statins helpful in preventing incidence and progression of the disease Rejection Most likely to occur in the first 3-6 months Symptoms: fatigue, premature ventricular contractions, heart failure, myocardial infarction Graded 0-4, 4 being the worst Three types: hyper-acute, acute vascular, and acute cellular Most common is acute cellular rejection Factors associated with acute cellular rejection: Younger, female, non O blood type, donor specific mismatch, HLA mismatch, CMV +, and OKT3 sensitization Acute vascular rejection has greater mortality than acute cellular and associated with a 10 fold increase in TCAD Endomyocardial biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis of rejection Immunosuppression Consequences of immunosuppression: malignancy, infection, steroid induced osteoporosis Current agents are fairly non specific because they inhibit lymphocyte subsets rather than act directly at donor specific allo-antigens Blunting of T lymphocyte is extremely important post transplant because they initiate antigen recognition and moderate allograft rejection B lymphocyte activation- humoral component is also important Calcineurin inhibitors key for improved survival of OHT. Tacrolimus use has overtaken cyclosporine in recent years. Many centers use peri-operative anti-lymphocyte antibody or anti-thymocyte globulin Steroids (prednisone) still used in 71% of OHT Most common combination of drugs is Tacrolimus and MMF with/or without prednisone Azathioprine Converted into 6-Mercaptopurine Inhibits early step in de novo purine synthesis o Several steps of salvage pathway as well Ultimately inhibits DNA synthesis Impact most felt on actively dividing lymphocytes SE: Pancytopenia, GI upset/Diarrhea, Skin Cancers Mycophenolate Mofetil (Cellcept)(MMF) Hydrolyzed to Mycphenolic Acid Inhibits de novo (ONLY) guanine synthesis Activated Lymphocytes rely solely on this pathway Other cell lines not as affected Studies have shown decreased mortality compared to Azathioprine Superior to Imuran in prevention of B-Cell Activation (Antibody Mediated Rejection) SE: Leukopenia, GI Upset/Diarrhea, Skin Ca Cyclosporine (CSA, Gengraf, Neoral, Sandimmune) Blocks IL-2 Transcription Major SE: Nephrotoxicity, HTN, Neurotoxicity, Hyperlipidemia Other SE: Hirsutism, Gingival Hyperplasia, Liver Dysfunction Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are complex Frequent serum level monitoring required Neoral better bioavailability than Sandimmune Tacrolimus (Prograff, FK-506) Discovered in 1984 Macrolide Antibiotic Product of Stretpomyces tsurubanensis fermentation Improved SE profile from CSA (HTN, Renal Dysfunction, Hirsuitism, Gingival Hyperplasia) ? Less Acute Rejection Episodes Hyperlipidemia and DM worse mTOR Kinase Inhibitors Sirolimus (Rapamune), Everolimus (Afinitor) Isolated from Streptomyces hygroscopicus Discovered initially as an antifungal agent Some studies showing protection against and reversal of transplant vasculopathy SE: Poor Wound Healing, Hypertriglyceridemia, Renal Dysfunction, Fluid Retention, Leukopenia, ?Increased Rejection if used without CI. Induction Agents OKT3, Thymoglobulin, Simulect, Campath Used in ~ 50% of Heart Transplants Decreased need for CI’s Perioperatively Decreased Acute Rejection Early on Increased success with early steroid withdrawal Increased risk for PTLD Typically used in “High Risk” pts (AA, Renal Dysfunction, Elevated PRAs, ReTx) Around 3300 heart transplants are performed per year, the patients are living longer with 50% living more than 10 years post transplant. Increased survival has lead to an increase in non-cardiac procedures in OHT patients from 15% in 1990 to 34%. These patients are at higher risk for post-operative morbidity and mortality for most procedures and thus it is beneficial for anesthesiologists to be able to optimize these patients for non-cardiac surgery and be able to safely take care of them in the operating theater. Main issues for the anesthesiologist Understand the physiological and pharmacological interactions in a denervated heart Know the side effects of immunosuppression Understand risk of infection and potential for rejection Preoperative assessment Focus on graft function and possibility of rejection. A recent echocardiogram and myocardial biopsy will give provide this information. Assess patient activity level and general well being Rejection should be ruled out for elective surgery, acute or chronic rejection leads to increased morbidity and mortality. EKG, assess for silent coronary artery disease. Dysrhythmias are also common, 50% of patients, secondary to lack of vagal tone, possibly rejection or circulating catecholamines Rule out infection, chest x-ray for sure (Lung is most common source), patient may not have typical symptoms secondary to immunosuppression, physician must have a high index of suspicion Reducing or missing immunosuppression doses can lead to increased risk of rejection, do not stop without discussion with transplant team 75% of cardiac patients have hypertension, thus assessment of adequacy of control should be part of the pre-op workup Assess end organ function, liver, kidney and bone marrow function are major side effects of immunosuppressive drugs (See drugs above) Tacrolimus and Cyclosporine are followed by drug levels, assess when last drawn Intraoperative Management The heart is denervated so compensatory responses to physiologic changes are delayed Address antibiotic prophylaxis and duration. Loss of vagal tone leads to higher than normal resting heart rate Intact Frank-Starling curve and preload dependence for ventricular output No compensatory increase in heart rate with hypovolemia or hypotension, stroke volume will be increased by an increase in circulating catecholamines Vagolytic drugs will be ineffective Reduced myocardial response to exercise occurs 2-6 years post transplant Denervated heart responds normally to glucagon, norepinephrine, epinephrine and propranolol Caution if using spinal anesthesia because of delayed response to hypotension There is the possibility of prolonged neuromuscular blockade with cyclosporine and azathioprine, exercise caution with dosing. Tacrolimus and Cyclosporine lower the seizure threshold, avoid hyperventilation References 1) Taylor D, Stehlik J, Edwards L, et al. Registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: Twenty-sixth official adult heart transplant report- 2009. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2009; 28:1007-22. 2) Patarroyo M, Simbaqueba C, Shrestha M, et al. Pre-operative risk factors and clinical outcomes associated with vasoplegia in recipients of orthotopic heart transplantation in the contemporary era. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2012; 31(3): 282287. 3) Arnaoutakis G, George T, Allen J, et al. Institutional volume and the effect of recipient risk on short-term mortality after orthotopic heart transplant. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2012; 143(1): 157-167. 4) Leonard G, Davis C. Outcomes of total hip and knee arthroplasty after cardiac transplantation. The Journal of Arhtroplasty 2012; 27(6): 889-894. 5) Amarelli C, Salvatore De Santo L, Marra C, et al. Early graft failure after heart transplant: risk factors and implications for improving donor-recipient matching. Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery 2012. 15: 57-62. 6) Saito A, Novick R, Kiaii B, et al. Early and late outcomes after cardiac retransplantation. Can J Surg 2013; 56(1): 21-26. 7) Ashary N, Kaye A, Hegazi A, et al. Anesthetic considerations in the patient with a heart transplant. Heart Disease 2002;4: 191-198 8) Lee M, Cheng R, Kandzari D, et al. Long-term outcomes of heart transplantation recipients with coronary artery disease who develop in-stent restenosis after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol 2012; 109: 1729-1732. 9) Bhama J, Shulman J, Bernudez C, et al. Heart transplantation for adults with congenital heart disease: results in the modern era. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation 2013; 32:499-504. 10) Yeen W, Polgar M, Guglin K, et al. Outcomes of adult orthotopic heart transplantation with extended allograft ischemic time. Transplant Proceedings 2013; 45: 2399-2405. 11) Blasco L, Parameshwar J, Vuylsteke A. Anaesthesia for noncardiac surgery in the heart transplant recipient. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology 2009; 22: 109-113. 12) Swami A, Kumar A, Rupal S, et al. Anaesthesia for non-cardiac surgery in a cardiac transplant recipient. Indian J Anaes 2011; 55: 405-407.