science research paper for frohne

advertisement

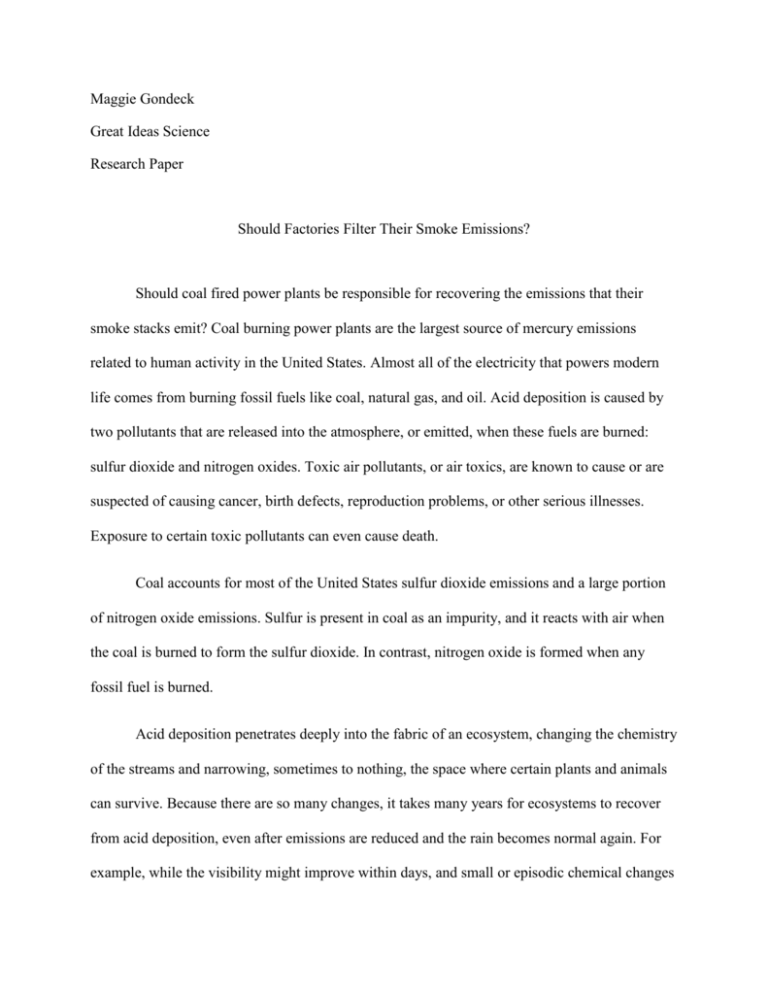

Maggie Gondeck Great Ideas Science Research Paper Should Factories Filter Their Smoke Emissions? Should coal fired power plants be responsible for recovering the emissions that their smoke stacks emit? Coal burning power plants are the largest source of mercury emissions related to human activity in the United States. Almost all of the electricity that powers modern life comes from burning fossil fuels like coal, natural gas, and oil. Acid deposition is caused by two pollutants that are released into the atmosphere, or emitted, when these fuels are burned: sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides. Toxic air pollutants, or air toxics, are known to cause or are suspected of causing cancer, birth defects, reproduction problems, or other serious illnesses. Exposure to certain toxic pollutants can even cause death. Coal accounts for most of the United States sulfur dioxide emissions and a large portion of nitrogen oxide emissions. Sulfur is present in coal as an impurity, and it reacts with air when the coal is burned to form the sulfur dioxide. In contrast, nitrogen oxide is formed when any fossil fuel is burned. Acid deposition penetrates deeply into the fabric of an ecosystem, changing the chemistry of the streams and narrowing, sometimes to nothing, the space where certain plants and animals can survive. Because there are so many changes, it takes many years for ecosystems to recover from acid deposition, even after emissions are reduced and the rain becomes normal again. For example, while the visibility might improve within days, and small or episodic chemical changes in streams improve within months, chronically acidified lakes, streams, forests, and soils can take years to decades or even centuries to heal. As emissions from the largest known sources of acid deposition, power plants and automobiles, are reduced, EPA scientists and their colleagues must assess the reductions to make sure they are achieving the results that Congress had anticipated. If these assessments show that acid deposition is still harming the environment, Congress may begin to consider additional ways to reduce emissions that cause acid deposition. They may consider additional emissions reductions from sources that have already been controlled, or methods that have already been controlled, or methods to reduce emissions from other sources. They may also invest in energy efficiency and alternative energy. The cutting edge of protecting the environment from acid deposition will continue to develop and implement cost effective mechanisms to reduce their impact on the environment. For now, it is much more economically efficient to capture the carbon dioxide that enters the atmosphere from the smokestacks of large centralized sources such as power plants, cement plants, fertilizer plants, and refineries. Indeed the researchers say the cost of removing carbon dioxide directly from the air would be so large that paying for it would require the equivalent of a ten dollar per gallon tax on gasoline. The cost estimates are similar to those presented earlier this year in a study that had been done earlier. Given the known health hazards from factory smokestack emissions, particularly those of coal-burning electric power plants, it is highly desirable to reduce the emissions at their source. One proven way of doing this is to install scrubbers in the emission system. The technology of scrubbers, which can remove a very large proportion of the sulfur dioxide from smokestack emissions, is constantly being refined. The technology of scrubbers, which can remove a very large portion of the sulfur dioxide from smokestack emissions, is constantly being refined. While one might imagine that scrubbers would be installed directly inside a smokestack, they can in fact be added at many points around it. Some scrubber installations require the addition of an entire building or complex to a coal plant. When soft coal or oil are ignited and burned, sulfur dioxide is produced. The main method of removing sulfur dioxide from emissions is to put the flue gas from industrial plants through a tank containing a sprayed mixture of powdered limestone and water. The resulting chemical reaction produces a synthetic form of the mineral gypsum, which can be adapted for the use of concrete or drywall. This can be done in a few different ways. In a wet scrubber, the untreated exhaust is sent through a spray chamber where fine water droplets knock down harmful particulates. The water at the bottom of the chamber enters a miniature water treatment plant where the sediments are removed before the water is recycled to be used again. Dry scrubbers use a granulated solid material or electrostatic technology to intercept the particulates, creating a dry waste product. These are not as common as wet scrubbers because of their higher costs of installation. In either case, before the flue gas reaches the scrubber reaches the scrubber, it may first pass through a filter that consists of some type of cloth bag to catch large particles. A second filter may be installed to catch very small particles after the flue gas leaves the scrubber. Before the 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments, the EPA regulated air toxics one chemical at a time. This approach did not work well. Between 1970 and 1990, the EPA established regulations for only seven pollutants. The 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments took a completely different approach to reducing toxic air pollutants. The Amendments required the EPA to identify categories of industrial sources for 187 listed toxic air pollutants and to take steps to reduce pollution by requiring sources to install controls or change production processes. It makes good sense to regulate by categories of industries rather than one pollutant at a time, since many individual sources release more than one toxic chemical. Developing controls and process changes for industrial source categories can result in major reductions in releases of multiple pollutants at one time. The EPA has published regulations covering a wide range of industrial categories, including chemical plants, incinerators, dry cleaners, and manufacturers of wood furniture. Harmful air toxics from large industrial sources, such as chemical plants, petroleum refineries, and paper mills, have been reduced to nearly 70 percent. These regulations mostly apply to large, or so called major sources, and also to some smaller sources known as area sources. In most cases, the EPA does not prescribe a specific control technology, but sets a performance level based on a technology or other practices already used by the better controlled and lower emitting sources in an industry. The EPA works to develop regulations that give companies as much flexibility as possible in deciding how they reduce their toxic air emissions, as long as the companies meet the levels required in the regulations. The 1990 Clean Air Act required the EPA to set regulations using a technology based or performance based approach to reduce toxic emissions from industrial sources. After the EPA sets the technology based regulations, the Act requires the EPA to evaluate any remaining risks, and decide whether it is necessary to control the source further. That assessment of remaining risk was initiated in the year 2000 for some of the industries covered by the technology based standards. Conway, Richard A. Environmental Risk Analysis for Chemicals. New York, NY. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, 1982. Feachem, Richard G, David J. Bradley, Hemda Garelick, D. Duncan Mara. Appropriate Technology for Sanitation. Washington D.C. the World Bank, 1980. Gould, Peter. Fire in the Rain. Baltimore, MA. John Hopkins University Press, 1990. Lict, William, Alfred J. Engel, Steven M. Slater. Control of Emissions from Stationary Combustion Sources. New York, NY. American Institute of Chemical Engineers, 1979. U.S. Environmental Agency. “Acid Rain.” http://www.epa.gov/acidrain.com (accessed March 19). Woodfall, David.”Acid Rain.” National Geographic. http://www.environment.nationalgeographic.com (accessed March 1).