Susan Zimmermann - Department of Gender Studies

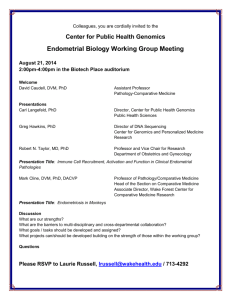

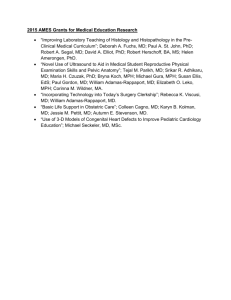

advertisement