Running head: USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS

advertisement

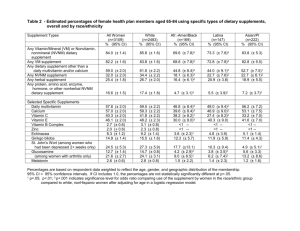

Running head: USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS Use of Stimulant and Weight Loss Supplements in a University Sample Sarah Pope Northern Arizona University 1 USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS 2 Abstract College students (n=235) from a Southwestern regional university were surveyed about their use of supplements containing bitter orange, ginseng, yohimbine (yohimbe), caffeine as well as OTC weight loss products. Participants also provided demographic information including gender, height, weight, ethnicity, smoking status, and age. Responses to the survey were used to determine characteristics associated with OTC stimulant and weight-loss products. No definitive relationship between BMI score (or status) was established. A significant relationship between gender and smoking status was observed. Further research in this area must be conducted to establish predicable behavioral and characteristic relationships among stimulant and weight loss supplement users. Keywords: Supplements, college students, stimulant use, BMI USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS 3 Use of Stimulant and Weight Loss Supplements in a University Sample Dietary supplements are a unique class of over-the-counter (OTC) products marketed and sold for use as health enhancers. Like pharmaceuticals, supplements are designed with the intent to be promoted as catalysts for optimal physical or psychological wellness. Non-vitamin, nonmineral supplements are marketed as anxiolytics, immune boosters, aids to weight-loss, memory enhancers, aphrodisiacs, et cetera. However, unlike pharmaceuticals, supplements are not subject to the kind of rigorous testing and regulation that a substance classified as a drug must undergo to be placed on the market. The 1994 Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (U.S. FDA, 1995) established that dietary supplements would be regulated as a food item opposed to a drug. As a result of this act, supplement products can be sold without prior evidence of effectiveness and are not governed by FDA provisions and requirements prior to introduction to the consumer market. Thus, the safety, purity, and efficacy of supplements varies greatly (Allison, Fontaine, Heshka, Mentore, & Heymsfield, 2001; Haller & Benowitz, 2000). Despite the often suspect nature of many supplements, they are widely consumed by a large number of individuals throughout the United States. It has been estimated that close to 160 million people living within the U.S. take some form of supplement daily (Perez, 2011). Data from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention nutrition survey has shown an increase in adult supplement use from 40% during 1988-1994 to 54% from 2003-2006 (Bailey, et. al., 2010). Commonly utilized supplements include those marketed for weight-loss and energy enhancement. The 2001-2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey reported that USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS 4 11.5% of respondents had used a non-regulated over-the-counter (OTC) product for weight loss within the year (Pillitteri, et. al., 2008). Another survey that assessed patterns of supplement use conducted between 1996 and1998 found that 7% of those who participated in the study had been or were currently using a supplement product for weight reduction (Blanck, Khan, & Serdula, 2001). The prevalence of OTC supplements used to decrease weight is particularly interesting given that demographic studies have shown that those most likely to use supplement products tend to have Body Mass Indexes (BMIs) considered to be within the normal range (Kirk, Cade, Barrett, & Conner, 1999; Radimer, Bindewald, Hughes, Bethane, Swanson, & Picciano, 2004). The correlation between low to normal BMI scores and supplement use strongly suggests one of two scenarios. First, the supplements could indeed be facilitating the reduction of previously overweight BMI’s. Secondly (and of particular interest in this study) the continued use of these weight-loss products despite the retention of a healthy BMI suggests a potential for product misuse or abuse. Populations who may be particularly vulnerable to inappropriate use of OTC products marketed for weight loss (or stimulant supplements used for the intent of weight reduction) include the college student demographic. Previous studies have reported rates of supplement use higher than the national mean, among college samples (Newberry, Beerman, Duncan, McGuire, & Hillers, 2001; Stasio, Curry, Sutton-Skinner, & Glassman, 2008). Student supplement consumption has been reported to be as high as 74.1%, while the average for national samples is closer to 19% (Stasio, Curry, Sutton-Skinner, & Glassman, 2008). Also, disordered eating behaviors tend to be more prevalent among young-adults, including those who pursue advanced education (Klemchuk, Hutchinson, & Frank, 1990). With this in mind, it is reasonable to suspect USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS 5 that supplements used to aid weight reduction may be incorporated into unhealthy body modification behaviors. Due to the lack of regulation imposed upon weight loss and stimulant supplements, users may be unaware of potential safety risks and/or lack of efficacy of these products. Barron and VanScoy (1993) reviewed a number of supplements sold between 1962 and 1992 focusing on the type of clinical testing (if any) these products underwent before being released to the consumer market. They found that only 42% had undergone any type of testing with results from these studies often providing very little support for efficacy among many supplements. Other, more recent, reviews have shown some support for many of the most commonly used supplements (Barnes, 2003; Bent, 2008). However, many of the trials conducted for these OTC products suffered from poor methodologies, variable preparation of these products, and often equivocal or conflicting results. It must be noted that the lack of evidence for these products does not inherently indicate an inability to affect physiological processes. More so, the lack of investigation raises important questions about the potential for negative side effects resulting from use of these untested supplements. A number of adverse effects have been reported for many OTC products resulting from contamination, supplement-pharmaceutical interactions, or as a result of the biological action of the supplement itself (Barnes, 2003; Bent, 2008; Housman & Dorman, 2008). Perhaps the supplement most notorious for its deleterious complications is the weight-loss product ephedra (also known as Ma Huang). Reports of cardiovascular complications resulting from ephedra use along with the clinical observance of toxicity due to many of the alkaloids found in this product led the FDA to issue a warning against use in 2003, leading to a legal ban of ephedra in 2004 (Dhar et. al., 2005). Despite the history of cardiovascular complications associated with many USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS 6 weight-loss supplements the FDA still maintains a laizze-faire approach in regard to regulation of supplement product safety and standardization (Heinrich, 2002). This means that any number of complications may arise from weight-loss or stimulant OTC product use without the user being informed of these possible effects beforehand. Because of potentially negative consequences that may result from supplement consumption, it is important to better understand the patterns that most often accompany weight loss and stimulant use amongst the college demographic. The purpose of this study was to gain insight into potential lifestyle and health patterns associated with those college students who use stimulant and weight loss supplementation. In particular, we wanted to discover if there was a relationship between stimulant/weight loss supplement use and BMI within the student sample. In attempt to answer this question, this study surveyed an adult sample of undergraduate students about their supplement use. Duration and frequency of use for many popular weight-loss and stimulant products such as bitter orange, yohimbine and ginseng were examined and compared to reported BMI scores. Method Participants Adult college students (mean age 20.2±4.7 years) recruited from Northern Arizona University psychology courses participated in this study. Of the 235 students who participated, approximately 70% were female, and 95% identified as Caucasian. Involvement in this study was completely voluntary and anonymous. Responses were not included if participants did not agree to participate following an informed consent procedure or were not at least 18 years old. Compensation was given in the form of extra credit for their enrolled psychology course. Materials and Procedure USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS 7 Participants completed the survey using an online data collection system (SurveyMonkey). All data was collected within a four-month period during the Spring semester of 2009. After agreeing to informed consent, participants answered survey questions about their demographic status, height, weight, and use of stimulant and weight loss supplements. Participants were surveyed about their use of supplements containing bitter orange, ginseng, yohimbine (yohimbe), caffeine supplements as well as OTC weight loss supplements. All participants were debriefed after completing the survey and provided with contact information for the Principal Investigator of the study should they have any further questions or concerns. Results Survey responses were analyzed using a t-test and Pearson correlation. Analysis were considered to be significant if the p-value was at or below the set alpha level of .05. Mean BMI scores were compared between respondents who had used OTC stimulant products (ginseng, yohimbine, bitter orange, OTC weight-loss products, taurine, or caffeine supplements) within the past year and those who did not. Analysis revealed that the BMI for those who had used any of the previously listed stimulants were slightly higher (M=24.65, SD= 4.38) than those who did not (M=23.66, SD=5.52). However, this difference was not found to be significant t(226)=3.74 p=n.s. The prevalence of stimulant use by participant characteristics were analyzed using Pearson chi-square test. This analysis revealed a relationship between current smoking status and stimulant use c2(2, N=235)= 17.95 p=.00 (see figure 1) as well as gender and stimulant use c2(1, N=235)=6.71 p=.01 (see figure 2). Discussion USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS 8 This study attempted to determine whether there is a predictable relationship between BMI and stimulant use. In particular, we wished to assess whether BMI status (overweight, under weight, etc.) could be used as a predictor of stimulant use. However, this sample fails to reveal significant differences between mean BMI. The majority of participants reported normal BMI status (see table 1) and this trend was further demonstrated by the mean BMI scores of both stimulant users (24.65) and non-users (23.66). This observation may be a reflection of the general popularity of stimulant use among this college sample, the majority of respondents (55.9%) reported use of at least one stimulant product within the past year. Ginseng was by far the most utilized stimulant supplement, with 36.2% of respondents reporting use of this stimulant within the year of survey participation. Ginseng was chosen as a supplement for this survey due to the fact it is often marketed to the public as an energizing agent. However, ginseng is advertised for a number of uses including female sexual enhancement (Polan, Hochberg, Trant, & Wuh ,2004), to reduce stress (Norred, Zamudio, & Palmer,2000), improve immune function (Liou, Huang, & Tseng, 2005), even to treat cancer (Jung, et. al., 2011). The wide-spread use of products such as ginseng within this sample suggests there may be a variety of interpretations regarding mechanism of action for these supplements. Thus, there may be wide variation between participants in regard to reason for use, or ascription of efficacy. Because supplements are not required to have a validated mechanism of action, nonprescription products (like ginseng) can be marketed for any purpose. This lends to a general confusion about how, if, or when these products should be used. Of the 85 participants who had used ginseng, there could be 85 different reasons for use. Future research in this area might wish to focus on assessing both psychological as well as physiological reasons for use of stimulant USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS 9 supplements. Assessment of perceived pharmacological properties would allow research to focus on specific supplement which are known for their use as stimulant and/or weight-loss products. These specific products could then be used to assess potential relationships between use and BMI status. The specific purpose of this study was to determine if there was a relationship between stimulant use and BMI among college students. More broadly, the general goal of this study was to determine whether certain lifestyle patterns or participant characteristics were associated with college student use of stimulant and weight loss products. Within this focus, we were able to determine two characteristics that were significantly related to use of the designated supplements within this study. Analysis revealed a relationship between gender and stimulant/weight-loss supplement use. Specifically, it appears that a higher proportion of men use stimulant products compared to those who identified as female (see figure 2). This observation is contrary to previous studies which have demonstrated that use of supplements is more common among female cohorts (Bailey, et. al., 2011; Blanck et. al, 2007; Pillitteri, et. al., 2008). However, many of the studies that have recognized a female preference for supplement use examined a variety of supplements opposed to stimulants in particular. The male partiality for OTC products observed in this study is more congruent with research that has delineated characteristics of illicit stimulant users, which have demonstrated that stimulants tend to be more often used by male college students (Hall,Irwin, Bowman, Frankenberger, & Jewett, 2005; Low, & Gendaszek, 2002). Another significant relationship noted within this study was that between smoking status and stimulant use. A higher proportion of current and former smokers used stimulant products within this sample (see figure 1). This phenomenon seems reasonable for a number of reasons. USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS 10 First, smoking is often used to augment weight loss (Bean, et. al, 2008; Grogan, Hartley, Conner, Fry, & Gough, 2010). If the participants in this study were using the products observed here for the purpose of weight reduction, it would be expected that other behaviors associated with weight management (both healthy and harmful) may be reported in conjunction with stimulant use. Also, nicotine is a known central nervous system stimulant; its use has long been associated with the consumption of other stimulants (both illicit and legal) and is often used as a predictor of non-nicotine stimulant abuse (Weinberger, & Sofuoglu, 2009). Limitations and Future Directions It should be noted that there was number of issues with the present sample. In particular, the effect size for this study was rather small (Cramer’s V was given a value of 0.10). This causes one to wonder whether some of the observed trends, such as a higher mean BMI score for stimulant users, would have displayed statistical significance with an increase in power (such as increased sample size). Also, the majority of participants were gleaned from the psychology department of NAU, potentially biasing the sample in unforeseen ways. To increase power and generalizability to the college population, future research should attempt to increase both the sample size and incorporate participants with a variety of academic focuses. As mentioned previously, the FDA does not regulate OTC supplements. As such, many of the products marketed as stimulant or weight loss supplements are also promoted and used for a variety of reasons unrelated to metabolic or cognitive enhancement. Potential studies would benefit from first collecting surveys that aim to establish which supplements are most often being used for the purpose of weight-loss or to improve performance. If these products were identified, more information regarding participant characteristics (such as BMI status) could be acquired to assess associations with these specific supplements. USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS 11 Although this study used BMI as a potential predictor of supplements being used to augment body modification practices, there are a number of other characteristics associated with attempted weight reduction. Noted here was a relationship between smoking status and stimulant/weight loss supplement use. It was also mentioned that nicotine often accompanies weight reduction efforts. However, there are a number of other behavioral indicators of a body image focus, such as time spent exercising, skipping meals, or excessive thoughts about weight. Any number of these indicators could be incorporated into further research on weight loss practices and supplement use within the college population. USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS 12 References Allison, D.B., Fontaine, K.R., Heshka, S., Mentore, J.L., & Heymsfield, S.B. (2001). Alternative treatments for weight loss: A critical review. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 41, 1-28. Bailey, R. L.,Gahche, J. J., Lentino, C. V., Dwyer, J. T., Engel, J. S., Thomas, P. R.,Betz, J. M.,Sempos, C. T., & Picciano, M. (2011). Dietary supplement use in the united states, 2003-2006. Journal of Nutrition, 141(2), 261. doi:10.3945/jn.110.133025 Barron, R., & VanScoy, G. (1993). Natural products and the athlete. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 27 (5), 607-615. Bean, M. K., Mitchell, K. S., Speizer, I. S., Wilson, D., Smith, B. N., & Fries, E. A. (2008). Rural adolescent attitudes toward smoking and weight loss: Relationship to smoking status. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 10(2), 279-286. doi:10.1080/14622200701824968 Bent, S. (2008). Herbal medicine in the united states: Review of efficacy, safety, and regulation. JGIM: Journal of General Internal Medicine, 23(6), 854-859. doi:10.1007/s11606-0080632-y USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS 13 Blanck, H. M., Serdula, M. K., Gillespie, C., Galuska, D. A., Sharpe, P. A., Conway, J. M., . . . Ainsworth, B. E. (2007). Use of nonprescription dietary supplements for weight loss is common among americans. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 107(3), 441447. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2006.12.009 Dhar, R., Stout, C. W., Link, M. S., Homoud, M. K., Weinstock, J., & Estes III, N. A. Mark. (2005). Cardiovascular toxicities of performance-enhancing substances in sports. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 80(10), 1307-1315. Grogan, S., Hartley, L., Conner, M., Fry, G., & Gough, B. (2010). Appearance concerns and smoking in young men and women: Going beyond weight control. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy, 17(3), 261-269. doi:10.3109/09687630802422019 Hall, K., Irwin, M., Bowman, K., Frankenberger, W., & Jewett, D. (2005). Illicit use of prescribed stimulant medication among college students. Journal Of American College Health, 53(4), 167-174. Haller, C. A. B.,Neal L. (2000). Adverse cardiovascular and central nervous system events associated with dietary supplements containing ephedra alkaloids. New England Journal of Medicine, 343(25), 1833. doi:10.1056/NEJM200012213432502 Heinrich, J. (2002). Dietary supplements for weight loss: Limited federal oversight has focused more on marketing than on safety: GAO-02-985T. GAO Reports, , 1. USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS 14 Housman, J. M., & Dorman, S. M. (2008). Dietary and sports supplements: The need for a systematic tracking system. American Journal of Health Studies, 23(1), 35-40. Jung I. L., Young W. H., Tae W. C., Hyun J. K., Sung-Moo, K., Hyeung-Jin, J., & ... Kwang S. A. (2011). Cellular Uptake of Ginsenosides in Korean White Ginseng and Red Ginseng and Their Apoptotic Activities in Human Breast Cancer Cells. Planta Medica, 77(1), 133140. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1250160 Klemchuk, H. P., Hutchinson, C. B., & Frank, R. I. (1990). Body dissatisfaction and eatingrelated problems on the college campus: Usefulness of the eating disorder inventory with a nonclinical population. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 37(3), 297-305. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.37.3.297 Liou, C., Huang, W., & Tseng, J. (2005). Long-Term Oral Administration of Ginseng Extract Modulates Humoral Immune Response and Spleen Cell Functions. American Journal Of Chinese Medicine, 33(4), 651-661. Low, K., & Gendaszek, A. (2002). Illicit use of psychostimulants among college students: a preliminary study. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 7(3), 283-287. Perez, R. (2011). Vitamin supplements: Hope vs. hype. Tufts University Health & Nutrition Letter, 29(6), 1. USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS 15 Polan, M., Hochberg, R., Trant, A., & Wuh, H. (2004). Estrogen bioassay of ginseng extract and ARGINMAX, a nutritional supplement for the enhancement of female sexual function. Journal Of Women's Health (15409996), 13(4), 427-430. Newberry, H., Beerman, K., Duncan, S., McGuire, M., & Hillers, V. (2001).Use of nonvitamin, nonmineral dietary supplements amount college students. Journal of American College Health, 50 (3), 123-129. Norred, C. L., Zamudio, S., & Palmer, S. K. (2000). Use of complementary and alternative medicines by surgical patients. AANA Journal, 68(1), 13-18. Pillitteri, J.L., Shiffman, S., Rohay, J.M., Harkins, A.M., Burton, S.L., & Wadden, T. (2008). Use of dietary supplements for weight loss in the United States: Results of a national survey. Obesity, 16 (4), 790–796. doi:10.1038/oby.2007.136 Stasio, M. J., Curry, K., Sutton-Skinner, K., & Glassman, D. M. (2008). Over-the-counter medication and herbal or dietary supplement use in college: Dose frequency and relationship to self-reported distress. Journal of American College Health, 56(5), 535548. USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994. (1995).College Park, MD. http://www.fda.gov/food/dietarysupplements.html> Accessed 5 October 2011. Weinberger, A. H., & Sofuoglu, M. (2009). The Impact of Cigarette Smoking on Stimulant Addiction. American Journal Of Drug & Alcohol Abuse, 35(1), 12-17. doi:10.1080/00952990802326280 16 17 USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS Table 1 BMI Status of Respondents* Underweight BMI Category Normal Overweight Obese Stimulant User 7.32 58.54 20.33 13.82 No Use 4.85 62.14 23.31 9.71 *Value Represents % of respondents 18 USE OF STIMULANT & WEIGHT LOSS SUPPLEMENTS % Use Within Status Figure 1 Prevalence of Stimulant Use by Smoking Status 1 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 use no use current former Smoking Status never % Use Within Gender Figure 2 Prevalence of Stimulant Use by Gender 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 use no use male female Gender