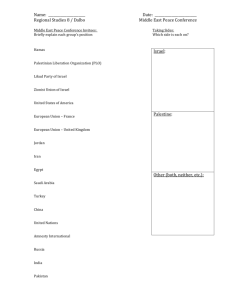

View/Open - AUC DAR Home - The American University in Cairo

advertisement