File - Lifepoint kids

advertisement

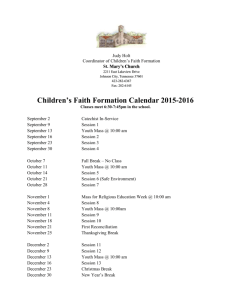

ABC’s of Spiritual Growth Rick Chromey The secret to creating lifelong faith is understanding the ABCs of developmental issues... Great Minds Think Alike? Over the past century, several notable minds have constructed theories that impact spiritual development. Jean Piaget developed ideas on cognitive growth. His well-tested theory suggests our minds grow and change in stages. For children, these stages are: sensorimotor (0-2), preoperational (2-7), concrete operations (7-11), and formal operations (11 and up). Erik Erikson helped us understand personality development. His theory suggests who we "are" is the result of resolving "crises" at various ages. For children, these crises are: trust vs. mistrust (ages 0-1.5), autonomy vs. shame/doubt (1.5-3), initiative vs. guilt (3-6), and industry vs. inferiority (7-12). Lawrence Kohlberg outlined how morals develop. His theory suggests, among other things, that age has no impact on moral growth (Translation: You can be an adult and have the morality of a child). For children, his suggested moral levels are: rules obeyed by reward or punishment (4-7), rules obeyed by agreement with self (7-10), and rules obeyed if others agree (10 and above). James Fowler helped us understand faith stages. Working from basic assumptions of cognitive and personality development, he suggested four primary stages for children: primal or "prefaith" (0-3), intuitive/projective or "fantasy" (3-7), mythic/literal or "formation" (7-11), and synthetic/convention or "patchwork" (12 to adult). What The Experts Say About Children's Spiritual Development Daniel is a bubbly 2-year-old. He eagerly and fearlessly topples and tumbles, runs and rumbles through the room. Every corner is a cave to explore, every object a new treasure. Occasionally, his curiosity causes a crash, but the bumps and bruises serve as testimony to growth. Faith is feeling. Rachel is a tender and quiet 7-year-old. Slightly mischievous, she enjoys laughter. She's learned to push buttons and find limits…sometimes. Gregarious and goofy, Rachel loves making friends -- especially with her teachers. Faith is mimicking adult mentors. Sarah is a dramatic and dynamic 10-year-old who stands on the edge of adolescence. Her body will soon forever change. Sarah is discovering her strengths and eagerly explores new interests. She's also found friends who influence her decisions. Sarah's faith is guided by new cognitive abilities that allow her to better understand her beliefs. Faith is now more personal. All three are learning. Each child is growing. Faith doesn't develop within a vacuum. It isn't microwaveable. It isn't a quick fix or simple solution. In fact, faith more resembles a crockpot or a long trip. It's not a momentary decision, but a lifelong journey. It's imperative to note that no two children are alike. The faith journey -- dependent upon home, cognitive/personality/moral development, and outside experiences -- will mark each child differently. Consequently, spiritual programming and curricula must reflect a basic assumption that we can guide and guard, but we can't control and coerce, how a child's faith evolves. How does faith develop? How do children learn to love and follow Jesus? Ultimately, faith is rooted in attitudes and feelings that mature into special relationships where commitments are created and decisions are later made. The process is similar to fitting shoes. Different ages have different sizes and shapes. The secret to creating lifelong faith is understanding the ABCs of developmental issues. A Is for Attitudes (Birth to 3) Babies are cool. They burp and poop, drool and scream. Their entire existence is rooted in self-preservation and a complete reliance upon another individual. Comfort is job one. Learning is a close second. Infants and toddlers are learning machines. Practically every day presents a new problem, and every obstacle creates a new opportunity. Roll over. Crawl. Stand. Walk. Babies listen and learn. First they mimic, but in time they'll understand and dialogue. Da-da. Daddy. Daddy hold? Daddy want a cracker? Piaget called this the sensorimotor period because it's primarily physical in nature. Infants touch everything (and nearly everything they handle is seen, heard, smelled, or tasted). Babies experience their world and, due to primitive memory, rely more upon emotions than facts. Erikson suggested that infants experience the crisis of trust vs. mistrust. In other words, they fight to find faith in primary caregivers. This explains why some nursery babies cry for their mothers. It's a positive sign. Infants cry for consolation, and unless they trust the environment, their screams will intensify. For babies and toddlers, faith is a feeling. Consequently, faith development is forged through powerful, positive, and personal spiritual experiences. Learning is through the senses. When my son Ryan was a baby, a nursery teacher impressed me. She sang to the infants as they patted a big Bible: "I love to pat the Bible, the Bible…it's God's Word to me." As a parent, that became a prayer for my boy. Parental involvement is crucial at this age. In fact, churches miss a family ministry opportunity by resisting or preventing parents from participating in the nursery. What if parents were encouraged to serve one Sunday a month (or more) as a volunteer (while their child was in the nursery)? Faith development requires a home connection. The primary venue for babies' faith development is the church nursery. It's the breeding ground for future spiritual attitudes. Consequently, it should be a safe, secure place that elicits a baby's trust. How does it look? Babies love large, colorful visuals and toys. Is it a loud place (crying babies set off other babies)? Is it staffed with volunteers who view nursery duty as ministry more than baby-sitting? Is there a basic baby curriculum? Are infants viewed as spiritual learners? B Is for Bonds (Ages 3-6) Preschoolers love life, and they have healthy self-concepts. Ask them about their intelligence, and nearly all will rank themselves as geniuses. Ask them about their futures, and you'll find dreams of doctor or firefighter mingled with Superman and Spy Kids. Invite them to use their talents, and preschoolers will happily draw, sculpt, construct, dance, dialogue, sing, or mimic. Preschoolers also seek connection -- in the family, at Sunday school, and with God. Cognitively, Piaget outlined the preschool years as preoperational. Simply, their minds now use symbols, classifications, numbers, and cause/effect. A preschooler no longer needs to touch (like an infant) to understand. But his mental abilities remain rather primitive. Consequently, preschool teachers can easily and unintentionally invoke faith commitments young children don't understand. Because preschoolers can converse, they enjoy stories and religious traditions. Fowler calls this the intuitive/projective stage of faith. It's perception and production -- and it's easily manipulated. Preschoolers will perceive story (even myth) to be fact. And they will "intuitively project" their faith (for example, to Santa Claus or the tooth fairy). It's the fantasy stage of faith, and it's formed by trusting older models (whether parent, pastor, or teacher). My wife entered kindergarten believing a horse was a cow (because her father, in a humorous moment, taught this silly idea). She later learned otherwise, but it created a new problem. Who should she trust -- parent or teacher? Morality is parent-based. Mom and/or Dad reflect God. Consequently, this period is one of relationship and bonding. Many preschoolers can form insipid, faulty God-views if their dads are aloof, absent, or abusive. Preschool teachers can correct negative views and connect positive relational models. Erikson labeled the preschool years as a crisis of initiative vs. guilt. In these can-do years, preschoolers are excited and enticed to do everything. Consequently, church preschool teachers must model kingdom values such as grace, community, love, service, and worship. The preschool years are ripe to teach prayer and mission. It's the opportunity to communicate connection to the church -- not as a building, but as a body; not as a facility, but as a face. Erikson further theorized that preschoolers who learn they can't, will sense guilt. Guilty children are easily manipulated and managed. Hungering for belonging, they'll pray for salvation or be baptized long before they're ready or truly understand. Fear and guilt can follow children throughout life (causing many adults to live as emotional cripples). Ultimately, a preschool faith is "fitting in" or belonging. The home-church connection is important. Unfortunately, preschool teachers must also minister in spite of family dysfunctions at times. Consequently, do your preschool workers model Christ? church values? kingdom principles? Do they teach preschoolers faith commitments (prayer, service, sacrifice) or fear and guilt (using bribes, intimidation, or manipulation)? Developmental experts believe the first six years mark a child for life. By age 7, the "personality" mold has been cast. And faith -- while still premature -- has formed enough to guide future decisions. C Is for Commitments (Ages 7-9) Young children are learning machines. With limitless energy and boundless creativity, they laugh and learn and love. Erikson suggested that the primary childhood conflict was one between industry and inferiority. Children become more peer-conscious and, consequently, discover personal strengths (industry) or weaknesses (inferiority). Younger children retain their can-do attitudes, but now see it tempered with some reality. Child sports clearly reveal this truth. Some community sport leagues cater to preschoolers. But children play sports for different reasons. Preschoolers play for fun. Young children participate because they sense approval (parent, coach, peer) while older children play because they're good and they're wanted (belonging). It's true with any hobby or interest (musical, educational, spiritual). The older a child gets, the more his decisions reflect inner values and beliefs. If kids don't belong, it's "so long." Piaget argued that younger children are concrete thinkers. They build on previous cognitive skills and master spatial and inductive/deductive reasoning. For example, while a 7-year-old realizes a clay ball rolled into a sausage shape retains the same amount of clay, a 9-year-old recognizes the weight stays similar too. Consequently, Bible learning can include maps, charts, and mental aids. Fowler adds that faith is mythic/literal for younger children -- it's either fact or fiction. The classic example is the holiday movie Miracle on 34th Street, where a young girl struggles to believe in Kris Kringle. Unlike most children, she's been taught Santa doesn't exist. Now she's faced with a reality and a commitment (to either her mother's "anti-Claus" ideology or her new friend named Kris). Faith development is similar. In fact, children who still believe the Santa myth can struggle with a historical Jesus (especially when Jesus is sometimes presented as a cartoon character while the mall Santa is a real person). Separating fact from fiction is vital. But it's not enough to break bubbles ("There is no Santa Claus") because younger children readily create their own fantasy myths, such as having imaginary friends. Nevertheless, as cognitive abilities and peer pressure changes, children do to. Many faith experts believe children aren't ready to embrace adult faith commitments until they no longer accept myths as reality. That's why younger children first make commitments to the faith as an attempt to follow someone -- Jesus, pastor, parent, teacher, or a peer. God is a "family" concept: a community of believers. This explains why myths (Santa Claus) are eventually abandoned for truth (Jesus). The community may honor and enjoy a myth for a season, but not year-round. Children eventually figure this out. Moral development is equally important. Younger children, according to Kohlberg's theory, practice selfbased morality or "I'll obey if I agree." This morality is a shift from early obedience to reward or punishment. Younger children obey for more selfish reasons than adult-imposed bribes or bans. Consequently, teachers and parents need to affirm positive moral commitments -- not with prizes or gifts, but with substantive praise, such as, "Johnny, thanks for being kind and gathering the trash." D Is for Decisions (Ages 10-12) Preteens are decision-makers. In fact, if their faith has productively and positively developed, by age 10 children will make pronounced and powerful individualized faith commitments. They'll create innovative ideas that serve family, church, and community -- sometimes with little adult intervention. Cognitively, older children evolve into abstract thinkers or, according to Piaget, possess "formal operations." Not limited by time or space, children think outside boxes, understand allegory, appreciate metaphor, and create hypotheses. For many children, this is when abstract faith rituals such as baptism and communion become meaningful. It's the moment for decision: salvation, Christian service or sacrifice of time, treasure, or talent. Unfortunately, many preteens also stop coming to church. Why? It's the fruit of making Christianity more like "churchianity" -- where church is considered a club like Boy Scouts and merit (badges, prizes, deeds) means more than purpose. Perfectionism is the spiritual gift for many "church kids." Works, or doing, is how you belong to the club. Furthermore, the home is ground zero. Older children reflect their parents' faith. Apathy, low commitment, and absenteeism are mirrors of a child's spiritual home life. Many boys are diagnosed with ADD and in upper elementary are classroom terrors. But for many unmanageable boys, ADD can mean "absent dad disorder." Fathers provide stability and structure for boys. The fatherly influence in the home -- whether by death, divorce, or other life priorities -- is missing. Kohlberg suggests that older children obey from peer agreement. Cheating? Sure, everybody does. Listening to "bad" music? All their friends do. Getting confirmed or baptized? Absolutely -- it's expected. Many children make moral decisions based more on peer acceptance and pressure than personal conviction. As a result, later faith development includes a healthy and expected amount of doubt as earlier commitments are re-evaluated. Consequently, teachers of older children need to challenge and encourage personal faith decisions. Faith needs to be 24/7/365 for older kids. However, many preteens see no personal life application. I once watched some sixth-graders, when asked by the teacher to "show" their Bibles (for a prize), grab Bibles from a nearby shelf! They got the prize but missed the point. The Bible never left church, and their faith is compartmentalized. Preteen faith reveals the success of children's ministry. If preteens are involved, excited, and committed to prayer, Bible study, worship, mission, and bringing friends, then that's success. Preteen faith also reveals a good home-church connection. ••• Babies grow up. Children mature. The seeds of faith -- acceptance or rejection -- are planted early. As children grow, so does faith. Faith that doesn't fit will eventually be abandoned. The goal of faith development is continual resizing and reinvention. We can't expect a size 4 faith to last a lifetime. We must provide faith that's culturally relevant and has personal meaning. As children's ministers, our job is to fit and form Christ so faith fashionably walks. Success is whether faith still "wears" later in life. It's not in numbers, but in commitments to God. Children crave a faith that's understandable, relevant, and applicable. They want a faith that doesn't wear out. Come to think of it, so do I. Rick Chromey, D. Min., is a professor, trainer, and consultant in children's and youth ministry, living in Meridian, Idaho. Please keep in mind that phone numbers, addresses, and prices are subject to change.