Coordination, Investment Promotion, Linkages and Employment

advertisement

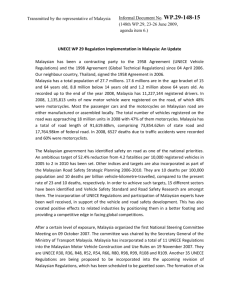

Professor Paul M Lubeck Acting Director, African Studies Program Johns Hopkins University-SAIS The Challenge of Coordination, Investment, and Employment for Economic Reconstruction in North Western and North Eastern States of Nigeria National Institute of Legislative Studies Abuja, Nigeria November 16-17, 2015 The Challenge: Economic Reconstruction in the North East and North West Zones The nineteen northern states of Nigeria represent 73 percent of the territory of the Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN), roughly twice the size of Germany, and account for approximately 60 percent of Nigeria’s total population (i.e. 108 million). This means the population of the northern states is larger than Ethiopia, Africa’s second largest state. Here we focus solely on economic reconstruction in the thirteen states within in the North East and North West zones which, unfortunately, register some of the world’s worst human development indicators. Regrettably, what these figures portray is a nation undergoing an increasingly violent process of regional polarization. Over the past decade, despite an impressive uptick in aggregate rates of economic growth and rising per-capita incomes in the oil-rich, better educated and economically dynamic southern states, Nigeria is becoming spatially polarized and socially bifurcated into a modernizing south, nurtured by superior infrastructures, consumer demand from a rising, educated middle class on one hand and, on the other, an introverted, economically stagnant, conflict-ridden, impoverished “North”. It is readily apparent that the Nigerian nation will not prosper unless all states participate in the benefits of economic growth. Similarly, policy makers from the North Western and North Eastern states are obligated to learn from the successful initiatives pioneered by the southern states so as to reverse the process of polarization. More alarming is the extremely serious situation in the North East zone where the so called Boko Haram insurgency is concentrated. This zone is now mired in a deep multidimensional social and economic crisis marked by rising fertility rates, a stagnant economy, millions of displaced persons, increasing criminality, feeble, indifferent 1 governance institutions, a Salafist-jihadi insurgency, millions of abandoned, undernourished and stunted children, and declining per capita incomes (e.g. 65-75% living below $1.25/day PPP). As the data within accompanying Tables confirm, decades of indifferent misrule by rent-seeking and fragmented elites have spawned an enormous, immiserated population of male youths, bereft of any hope for marriage, pathways to decent livelihoods or social inclusion. Unsurprisingly, after decades of criminal neglect in the face of flagrant political corruption, a minority of these enraged northern youths are revolting against the social order and misrule by older, senior generations by engaging in organized criminal and political violence. This paper assumes that the Boko Haram insurgency is the extreme outcome of a much larger and far deeper crisis in economic and political governance in the North East and North West zones, one that has taken decades to germinate but is relentlessly driving many forms of violent, criminal and extremist behavior. Boko Haram, therefore, should be understood as a predictable outcome, not the original cause of the crisis racking northern Nigeria. Since the drivers of this crisis are demographic in origin and rooted in the unemployment of youths, policy makers at the sub-national state level must design and implement new strategies to reduce the causes and increase opportunity for northern youths. To be sure, expectations are very high. Nonetheless, the integrity of the 2015 election offers policy makers a unique opportunity to implement social and economic policies that will bolster investor confidence while, simultaneously, offering tens of millions of northern youths greater hope for a dignified and productive life. What exactly is the northern demographic crisis and how does it generate violent behavior among northern Muslim youths? Since the age structure of any society, e.g. 2 the proportion of the population between 15-45, determines its future population growth, current demographic trends are constructing an enormous “youth bulge” in the North East and North West zones. We estimate that approximately 70 percent of the population in the overwhelmingly Muslim states of the Northwest and Northeast Zones are below 30 years of age. Map 1.1 - Total Fertility Rate by Zone 3 Map 1.2 - Women Under 19 Who Are Mothers or Pregnant with First Child 4 Map 1.3 - Percentage of Women Using Any Kind of Birth Control 5 Chart 1.1 - Children Under 5 Who Are Moderately or Severely Stunted Children Under 5 Who Are Moderately or Severely Stunted 60.0% 50.0% 40.0% 30.0% 20.0% 10.0% 0.0% North Central North East North West South East 2008 South South South West Nigeria Total 2013 6 Chart 1.2 - Women Who Received ANC From a Skilled Provider for Most Recent Pregnancy Women Who Received ANC From a Skilled Provider for Most Recent Pregnancy 100.0% 80.0% 60.0% 40.0% 20.0% 0.0% North Central North East North West South East 2008 South South South West Nigeria Total 2013 7 Map 1.4 - Women Age 15-49 Who Are Literate 8 Map 1.5 - Women Age 15-49 With No Education 9 Map 1.6 - Women Age 15-49 Whose Highest Level of Income Is Primary School 10 Map 1.7 - Women Age 15-49 Whose Highest Level of Income is Secondary School 11 Map 1.8 - Women Who Report Controlling Their Own Income The North West Zone, Nigeria’s most populous, most fertile and most Muslim zone, with a fertility rate since 2003 varies between 7.4 and 6.7 births per woman, closely parallels that of the Republic of Niger, a country ranked at the absolute bottom of the UNDP’s human security index. Similarly, it is not surprising that 36 per cent of girls between 15 and 19 in this zone are either pregnant or have already given birth. Therefore, the total 12 fertility rate and the structure of the population guarantee that enormous waves of impoverished male youths will be migrating to northern cities for decades to come. The northern crisis, therefore, is not primarily an economic crisis: rather it is driven by gender relations, specifically the social and economic status of northern Muslim girls and women. These statistics demonstrate that unless the health, educational and economic status of girls in these two zones are raised significantly, so as to reduce fertility rates to sustainable levels, both absolute and relative per capita incomes of all living in these two zones will inevitably continue to decline. Per capita incomes in these two zones will decline because, under any imaginable rate of investment or economic growth scenario, the northern economy will be incapable of generating an economic growth rate high enough to compensate for the high rate of population growth occurring within these zones. Therefore, unless total fertility rates are lowered by introducing responsible and realistic health and education policies, per capita income and living standards will decline and the risk that recruitment into violence-prone organizations will continue. State Governance: Mobilizing Public-Private Initiatives for Youth Employment Addressing the youth employment crisis in these two zones requires state policy makers at the sub-national level to wed public governance institutions at the state level with market-driven incentives so as to attract productive private investment for labor absorbing industries. For many northern policy makers, this means learning from the experience of comparable, Muslim-majority countries like Malaysia, Indonesia and 13 Turkey whose economies are far more advanced and, interestingly, where many northern Muslim elites send their children for higher education. Fortunately, under Nigeria’s democratic federal constitutions, state governors possess not only immense fiscal, territorial, legal and security powers, but they also control a statutory revenue allocation, (e.g. the federal account) derived from energy rents. Similarly, because FGN agencies delegate all multi-lateral, bi-lateral and federal economic programs to state administrations, any realistic strategy for northern economic recovery must recognize the pivotal role played by governors in recruiting investors, allocating land, managing industrial estates, siting infrastructures and managing regional economic planning authorities. State authority over land allocations means key labor-absorbing industries---urban construction, SMEs, industrial estates, and agricultural investment---will be subject to the state authorities. More importantly for youth employment, northern governors control elections, fiscal affairs, educational institutions, and social programs managed by Local Government Authorities (LGAs). The LGAs are important because they possess a hitherto unrealized potential for nurturing labor absorbing social enterprises as well as for providing social, educational and health services for northern youths adjusting an increasingly urbanized society. Given the constitutional authority vested in states, northern governors must be convinced to use their authority to solve the coordination problem. Currently, at the state level, the coordination function is fragmented, feeble, or completely absent, largely because development initiatives are dispersed among different ministries, planning agencies, federal agencies, international donors, contractors to multi-lateral agencies, special advisors to the governors and/or to insider-political patrons or “godfathers”. 14 Strong voices for re-industrialization routinely call for launching of the equivalent of a “Marshall Plan” to spearhead a northern recovery. Yet, few voices have proposed exactly what institutional mechanisms or what kinds of agencies will perform the coordination function among numerous, overlapping and often competing public, private sector and social sector actors. Implementation requires technocratic expertise and designated development agencies if the coordination problem is to be resolved. Key coordination function questions facing states in these two zones are: what agency will coordinate among the public actors, investors, industrial financial institutions and contractors from multi-lateral institutions? Which agency will perform the coordination function necessary to recruit labor absorbing firms, raise funds for infrastructures, train technical labor, articulate with FGN programs implemented by donor agencies, promote industrial linkages, rationalize “industrial clusters”, and evaluate future technical upgrading necessary for boosting value added in particular industries? What agency will collect, process, and disseminate reliable economic information for potential investors regarding existing industries, incentives, regulations, local partnerships and proposed infrastructures? Which state-level agency will facilitate the concerns of potential investors to agencies in the FGN? In federal states like Malaysia (e.g. Penang Development Corporation) and in semi-autonomous regions like Wales (Welsh Development Agency), industrial development agencies within subnational units (e.g. states) have proved very effective in performing the critical coordination function. The coordination problem raises the question whether the regional industrial agency model will promote industrial construction and employment generation in the two zones. Finally, competent state industrial authorities will require trained professionals with deep 15 private sector experience if duplication, confusion, waste and graft are to be avoided. Unfortunately, without a permanent, professionally staffed, industrial development agency, charged with providing coordination and continuity, a democratic change in governors not only risks the destruction of valuable industrial development projects, but also the state’s industrial- institutional memory. Economic reconstruction requires leaders in the North East and North West zones to pursue policies that nurture industries that increase productivity and employment. Policies should be realistic, market augmenting and truly “developmental” policies in the East Asian sense of the term. Not only must they define broad goals, they must set empirically verifiable and transparent performance targets so that outcomes, be they successes or failures, will be transparently accountable to technocrats and public monitors, e.g. elected local and state officials and independent civil society groups. In addition, these policies must mobilize public and private resources to upgrade the quality of educational institutions in ways that will prepare youths---male and female---to be able to produce goods and services for northerners with incomes and for southern Nigeria’s rising middle classes. This will require linking educational institutions more closely with private sector employers in different sectors. This strategy requires Nigerian states to create regional development agencies (RDAs) to perform the coordination function by not only promoting investment in productive industries but also by facilitating the linking of industries to social partners, educational institutions and sources of finance. Learning from the Malaysian Experience: The Penang Development Corporation 16 Many northern Nigerians are impressed with the economic and social performance of Malaysia since independence. Historically, this is understandable because Nigeria and Malaysia share many common experiences including a common colonial governor, Hugh Clifford. Both are multi-ethnic federations with large Muslim populations in which a form of shari`a law exists for Muslims. Colonized by the British under the doctrine of indirect rule, both retain Muslim titles and members the aristocracy are strongly represented in the civil service and political elite. And both countries have struggled to deal with tensions that arose from ethnic divisions of labor and education deficits which, in turn, produced compensatory programs to ensure federal character in employment and opportunities for indigenous communities. While both experienced ethnic conflict during the late sixties, the Malaysian policy response differed significantly from Nigeria. Map 1.9 - Political Map of Malaysia 17 Map 1.10 - Developmental Regions and Corridors of Peninsular Malaysia 18 In 1971 the Malaysian federal state institutionalized an economic and social reengineering program called the New Economic Policy (NEP) which called for the elimination of absolute poverty, the absolution of the ethnic division of labor, the creation of a Malay (Bumiputra) professional and entrepreneurial class and the redistribution of corporate equity according to ethnic identity. The accompanying demographic tables demonstrate the success of the program in terms of eliminating poverty, educating all citizens, offering opportunity for women and providing a foundation for social stability that attracted foreign investment. Today poverty has been effectively abolished and Malaysia’s adjusted per capita income (PPP) is over $17,500. Table 1.1 - Births Per Woman Malaysia Births Per Woman 2.18 Source: CIA World Factbook Indonesia 2.58 Table 1.2 - Women Age 15 and Above Who Can Read and Write Indonesia Malaysia Men 95.6% 95.4% Women 90.1% 90.7% Total 92.8% 93.1% Source: CIA World Factbook 19 Table 1.3 - Secondary School Participation, Net Enrollment Ratio 2008-2012 Men Indonesia Malaysia 74.4% 71.3% Source: CIA World Factbook Table 1.4 Bumiputera Chinese Indian Other Incidence in poverty in Malaysia by ethnic group, 1970-2012 1970 1976 1979 1984 1987 1989 1992 1995 1997 64.8% 46.4% 49.2% 28.7% 26.6% 23.0% 17.5% 12.2% 9.0% 26.0% 17.4% 16.5% 7.8% 7.0% 5.4% 3.2% 2.1% 1.1% 39.2% 27.3% 27.3% 19.8% 10.1% 9.6% 7.6% 4.4% 2.6% 44.8% 33.8% 28.9% 18.8% 20.3% 22.1% 21.3% 22.1% 13.0% Source: Malaysian Department of Statistics, Malaysian Economic Planning Unit, World Bank 1999 12.3% 1.2% 1.3% 25.5% 2002 9.0% 1.0% 3.4% 8.5% 2004 8.3% 0.6% 2.7% 6.9% 2007 5.1% 0.6% 2.9% 9.8% 2009 5.3% 0.6% 2.5% 6.7% 2012 2.2% 0.3% 2.5% 1.5% Chart 1.3 – Incidence of Poverty in Malaysia by Ethnic Group, 1970-2012 20 Table 1.5 – Tertiary Education in Malaysia by Ethnic Group, 1980-2000 Tertiary education in Malaysia by ethnic group, 19802000 (% of enrollments) 1980 1990 2000 Bumiputera 49.24% 59.65% 59.92% Chinese 39.71% 32.13% 32.52% Indian 8.61% 6.27% 6.80% Other 5.43% 1.95% 0.76% Source: "Access to and Equity in Higher Education - Malaysia," World Bank, 2012 Table 1.6 – Total Enrollment in Tertiary Education in Malaysia, 1970-2000 Total enrollment in tertiary education in Malaysia, 1970-2007 (% total population) 1970 1980 1990 2000 2007 Percent of population 0.60% 1.60% 2.90% 8.10% 24.40% Source: "Access to and Equity in Higher Education - Malaysia," World Bank, 2012 Table 1.7 – Individuals With Higher Education, 1980-2000 Individuals with higher education, 1980-2000 (% total population with higher education) 1980 1991 2000 Male 67.79% 58.40% 50.93% Bumiputera Female 32.21% 41.60% 49.07% Male 69.53% 60.48% 54.64% Chinese Female 30.49% 39.52% 45.36% Male 66.82% 63.39% 56.28% Indian Female 33.18% 36.61% 43.72% Source: World Bank, Malaysian Department of Statistics, Malaysian Economic Planning Unit Table 1.8 – Secondary Education, Female Secondary education, female (% gross) School enrollment, tertiary, female (% gross) 1970 1975 1980 1985 40.97% 43.25% 47.62% 49.11% No data No data 3.07% 5.02% Source: World Bank and Malaysian Department of Statistics 1990 50.81% 5.53% 1995 51.21% 7.06% 2000 51.16% 26.47% 2005 51.26% 30.90% 2010 50.53% 40.85% Chart 1.4 – Female Education in Malaysia, 1970-2010 21 Table 1.9 – Total Fertility Rate Fertility rate, total (births per woman) 1970 1975 1980 1985 4.872 4.209 3.789 3.656 Source: World Bank and Malaysian Department of Statistics 1990 3.515 1995 3.339 2000 2.825 2005 2.216 2010 2.002 Table 1.5 – Total Fertility Rate Table 1.10 – Employment in Agriculture, Female 22 1970 1975 1980 1985 Employment in agriculture, female (% female employment) No data No data 43.80% 33.80% Employment in agriculture (% of total employment) No data No data 37.20% 30.40% Source: World Bank and Malaysian Department of Statistics 1990 25.30% 26% 1995 16.90% 20% 2000 14.0% 18.40% 2005 10.20% 14.60% 2010 8.50% 13.30% 1990 17% 1995 9% 2000 8% 2005 6% 2010 4% 1990 70.76 1995 71.86 2000 72.85 2005 73.84 2010 74.50 Table 1.11 – Poverty Rate Poverty rate (government poverty line) 1970 1975 1980 43% 39% 37% Source: Malaysian Department of Statistics 1985 20% Table 1.12 – Life Expectancy at Birth Life expectancy at birth, total (years) 1970 1975 1980 1985 64.46 66.40 68.06 69.50 Source: World Bank and Malaysian Department of Statistics Although the NEP virtually eliminated poverty and uplifted the economic and educational status of the Muslim Malays, it was not responsible for the innovations that enabled Malaysia to become a middle income country and a newly industrializing state whose exports are about 80 per cent industrial goods. Instead, the institutional innovations that propelled Malaysia to its current status was initiated as an experiment undertaken by one of the poorer states, Penang, to bolster employment since ethnic conflict of 1969 and the recent loss of their free trade status. Under the leadership of a brilliant Chief Minister (e.g. governor), the state of Penang transformed a moribund state economic development corporation, the Penang Development Corporation (PDC) into a dynamic, innovative regional development agency that emulated the policies pursued by Asian developmental states especially Singapore and Taiwan. Working closely with the chief minister who negotiated free trade zones and other incentives for electronics firms such as Intel, National, Motorola and Dell, the professional staff at the 23 PDC developed a strategy that constantly upgraded skills, nurtured linkages and industrial clusters and pursued technological services for high tech firms. Map 1.11 - Penang K-Worker Clusters 24 Map 1.12 - Penang Company Clusters The demonstration effect of the PDC’s success provoked other Malaysian states especially Johor, Kedah and Selangor to replicate the PDC strategy of EOI and FTZs. Again, the success of the Malaysian model is built on the foundation of social equity and redistribution but the dynamic growth and innovation that increased employment, raised incomes and lifted skill levels came from international firms and the linkages to local firms. 25 In addition to providing secure title to land and infrastructures, what lessons can the states from the North West and North East learn from the success of the PDC? The first lesson recommends creating a professional regional or state development agency directly under the governor and not subordinated to a state ministry personed by the civil service. The PDC employed highly motivated technocrats who understood the private sector, the market forces faced by the firms that they were recruiting. Second, the PDC encouraged managers working in the multinational firms to create local suppliers, service firms and linkages. Multinational firms desired local suppliers and subassembly firms so they fostered managers to create supplier firms that allowed them to focus their resources on more technically advanced and more profitable tasks, e.g. “a win-win” arrangement. Third, the PDC pursued what are called “developmental firms” with a vision for building up the capacity of the region. These firms understood the benefits of public-private collaboration and oftentimes seconded engineers to assist local firms to meet the quality standards of their suppliers. Fourth, the PDC organized producer associations for the supplier firms and built common technical and testing facilities to enable them to move to the next level. Fifth, in 1989, the PDC facilitated the creation of the Penang Skills Development Centre which integrated academic, public sector and private firms around the goal of increasing the number of skilled workers especially engineers and offering them credits, certifications and degrees that became part of the workers’ portfolios, e.g. their credentials (twelve other states have emulated the PSDC). Sixth, the PDC constantly supported the creation of SME services in order to incubate local firms whom they encouraged to become integrated into the production networks of Multinationals (see, http://smartpenang.my/). With these lessons from 26 Penang in mind, let us turn to the obstacles faced by Kano with an eye to evaluating the value of a state or regional development agency Kano: The Challenge of Coordinating Industrial Recovery Strategies In this section, I will present a summary of several economic reconstruction initiatives pursued by different leaders in Kano since 2004. Drawing on the experience of Penang and other regional development agencies at the state level, my objective is to inquire whether or not a coordinating agency like the PDC could have contributed to economic reconstruction in the leading industrial center of northern Nigeria. For at least the last two hundred years Kano city and its networks have constituted an innovative center of commercial, financial and industrial activity in West Africa. Before the collapse of petroleum prices and the imposition of structural adjustment policies (SAP) in the early eighties, Kano possessed at least 500 hundred manufacturing firms engaged in the light manufacturing of consumer goods, agro-processing, food, textiles and plastics for local, regional and West African consumers. Many industrialists were indigenous Kanawa or long term residents of Kano who possessed Nigerian citizenship and, equally important, Kano’s powerful merchant networks were closely integrated into the consumer goods manufacturers. A number of factors contributed to what is regrettably more than a quarter century of industrial decline: the deep devaluation of the Naira made it impossible for firms to purchase space parts and imported inputs; structural adjustment policies (SAP) implemented by the federal government crushed consumer demand for locally manufactured goods; cheaper imported goods, both smuggled and legal, challenged 27 local manufacturers and forced the closure of many firms and the incapacity of the Nigerian state to produce and deliver electric power raised the cost of production to prohibitive levels. Textile production for the domestic market, once the most advanced sector with excellent backward linkages with cotton producers and ginneries, employing more than 700,000 workers in Nigeria, have almost completely disappeared. The export-oriented tanning industry is the exception in part because of an export subsidy and the concentration of tanning among few firms. In general, however, neither the federal government nor the state governments have been able to implement an industrial policy capable of reversing the collapse of manufacturing in Kano and the associated decline in employment opportunities for youths in the North Western and North Eastern states. Driven by high fertility rates and the migration of youths to metropolitan Kano, the population of Kano had grown to about 4 million by 2004. Under-employment and unemployment have produced a vast number of male youths seeking work in the informal sector since employment at the industrial estates had dried up. At the same time as the return to democratic rule in 1999, the incidence of ethnic and religious conflict had increased significantly in Kano. In 2004, an especially destructive and widespread ethnic conflict erupted allegedly in retribution for the loss of local lives in Plateau State, e.g. the “Yelwa killings”. In response to reputational damage inflicted by the rioting and the withdrawal of investment capital from the city, a group of enlightened citizens formed the Kano Peace and Development Initiative (KAPEDI) with the intention of restoring the reputation of the city for commerce and tolerance. Forms were held and representatives from different 28 communities were invited to participate. The leaders conveyed a vision of Kano that was cosmopolitan and open to strangers who wish to trade and invest in the city. Leaders cited the long history of diversity as registered in the names of the wards of the Old City and made significant progress in area of peace, reconciliation and trust. The positive response to KAPEDI’s forums encouraged the leaders to seek funding and support for an Economic Summit focusing on the revitalization of Kano. In April 2006, with the support of donor agencies, the governor of Kano and Bayero University, the summit was held and over 1,000 people participated and/or attended the event. Papers were presented and a committee was created to publish the papers. Efforts to move the discussion forward to the level of industrial policy, however, founded on the shoals of political partisanship because of perceived differences between the state governor and the titular head of KAPEDI who was a minister in the ruling PDP government in Abuja. Interpretations of the breakdown of trust and communication among the parties vary but the outcome resulted in a stalemate. The Summit paper were not published and the state government, according to published reports, expressed no interest in collaborating on an economic revitalization or reindustrialization strategy. Here distrust among the leadership and the lack of a permanent state industrial development agency to coordinate the project appear to explain the failure of the Summit to contribute to the reconstruction of industry in northern Nigeria’s largest city. The Kano ICT Park as a Public-Private Initiative 29 One of the most innovative presentations at the Kano Economic Summit was made by a professor of electrical engineering from Bayero University who was the special advisor for technology to the Kano State governor. Appropriately entitled “Exploring New Business Opportunities in the ICT Sector”, the advisor reviewed the growth of the global knowledge economy, the success of Indian software industries and services, the value of E-governance, and Kano State’s plan to build an ICT Park to incubate businesses, conduct trainings and support local enterprises. The plan called for siting the ICT Park in the Ado Bayero building, obtaining FTZ status for occupants and for recruiting firms and instructional programs to fill the spaces of an 11 story building. The secure power source in the building was very attractive to firms from the IT industry and the project had the strong support of software firms, digital SMEs and many academics. The World Bank representative I interviewed about the Park supported the project as well. Whatever the pros and cons of this venture it was the most innovative and potentially productive project in support of the re-industrialization of Kano. Unfortunately, before the ICT Park could become fully operational, the sitting governor completed his second term, a former governor was brought back into office. Instead the building was converted into a temporary site for a new state university. Critics of this decision believe the ICT Park would have benefitted many businesses and provided support for the GSM Repair and Assembly Association. The leaders of the Association claim to have 5,000 youthful members in Kano and report being able to not only repair mobile phones but also to flash software into their memory cells. They lamented the demise of the ICT Park and pointed out that the government was establishing a ICT training center at Kura but it would not generate support for SMEs. In this instance, a 30 dedicated, professional development agency may have been able to provide continuity between administrations thereby salvaging a resource that would have anchored the IT industry in Kano. Concluding Thoughts on Strategies for Solving the Coordination Problem While it is true that Kano has made enormous progress in the area of infrastructure, housing estates and micro-credit, the industrial sector has not experienced a revival. The tanning industry exports approximately $700 million in finished ovine leather but linkages to finished leather products are extremely weak. There is great potential for backward linkages if a regional development agency was directed to increase the production of goats among small holders and women in the region. The tanneries experience a shortage of skins and import about half of those that they tan. In order for manufacturing and other industries to be reconstructed, the energy source for power must be solved. The absence of electric power adds between 30 and 50 percent to the cost of production according to industrialists. Solving the power problem requires public-private collaboration and the mobilization of the business and political communities around solving the power problem. Both the reconstruction of power services and rail services are necessary for the the revitalization of industry in these two zones. Given Nigeria’s abundant source of natural gas and several efforts to fund the piping of gas to the industrial areas of the Northwest states, the extension of the natural gas pipeline to the northern states constitutes an excellent project for the Northern Governor’s Forum to pursue. 31