Church - Vanderbilt University

advertisement

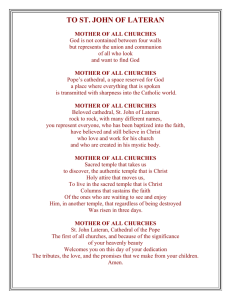

The Cambridge Dictionary of Christianity, General Editor, Daniel Patte (July 2010). © Copyright Cambridge University Press Church, Concepts and Life, Cluster 1) Introductory Entries Church, Concepts and Life: Doctrines of the Church Church, Concepts and Life: Feminist Perspectives Church, Concepts and Life: Names for the Church Church, Concepts and Life: Types of Ecclesiastical Structures 2) A Sampling of Contextual Views and Practices Church, Concepts and Life: In African Instituted Churches Church, Concepts and Life: In Asia Church, Concepts and Life: House Churches Church, Concepts and Life: In Latin America Church, Concepts and Life: In Latin America: Brazil: Base Ecclesial Communities (CEBs) Church, Concepts and Life: In Latin America: Ecuador: Base Ecclesial Communities (CEBs) Church, Concepts and Life: In North America Church, Concepts and Life: In Western European Theology 1) Introductory Entries Church, Concepts and Life: Doctrines of the Church. X Ecclesiology, the doctrine of the church, is one of the most widely discussed topics in contemporary theology, although it was only with the Reformation* that it became a separate chapter in Christian theology, when the question of the true church came into focus. The biblical term ekklesia (Gk “congregation,” “assembly”) denotes in the NT both the local and universal church. While the church came into existence at Pentecost as a result of the pouring out of the Holy* Spirit (Acts 2), the “founding” of the church is attributed to Jesus (Matt 16:18, a disputed verse). Among NT images for the church, the most often used are “people of God,” “body of Christ,” and “temple of the Holy Spirit.” Early creeds connect the church with the Holy* Spirit, forgiveness* of sins, and the coming of God’s Kingdom*. The Nicene* Creed (4th c.) gave a definitive understanding of the church as one, holy, catholic, and apostolic. As the body of Christ, the church is one and holy, because its Lord is. Catholicity (Gk cat-holos, “according to the whole”) means that the church not only is spread everywhere but also possesses the whole gospel*. All affirm these “marks of the church” – one, holy, catholic, and apostolic. Yet their exact meaning is disputed. For example, should holiness be located in the Lord or in the members? Should apostolicity be in terms of apostolic* succession of bishops or in terms of adherence to the apostolic word of the gospel? The Christian Church has undergone several major splits. Several Oriental Orthodox* churches* (e.g. Syriac*) disagreed with the Eastern Orthodox* and Roman* Catholic churches’ adherence to the Council of Chalcedon* (451). The 1054 split between the Western Church (Roman Catholic) and Eastern Church (Eastern Orthodox) resulted from the Filioque* dispute and other ecclesiopolitical factors. The 16th-c. division split the Western Church into Roman Catholic and Protestant* churches. Luther*, then other Reformers (Zwingli*, Calvin*, the English Reformers), began their activities with no intention of splitting the church; this schism became definitive only after the Council of Trent* (1545–63) and the founding of Protestant churches. The Radical* Reformers, out of which came Anabaptists* (Mennonites*), pushed an even more radical reform agenda with the idea of believers’ baptism* and the separation between church* and state. In 17th-c. England, the Baptist* Movement arose to continue this agenda. The independent* church movements (postdenominational or free churches) that rapidly grew in the late 20th c. and early 21st c. owed their beginnings to Baptists and Anabaptists. The rise to prominence of the Pentecostal* Movement (since the early 20th c.) and later of the Charismatic* Movement were a radical challenge to all churches in that they powerfully called them to be more receptive to the power and presence of the Holy* Spirit with charismata* and spiritual manifestations. For the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches, the ecclesiality of the church is based on the sacraments*, especially the Eucharist*, the legitimacy of which is guaranteed by a bishop* who stands in the apostolic succession. The Eastern Orthodox Church speaks of the Church as the image (see Icon; Iconography) of the Trinity* and as a mystery* (sacrament*), emphasizing its mystical and cosmological characters. Vatican* II (1962–65) similarly anchors the church in the Trinity and, unlike in the past, regards the earthly church as less than perfect; the church is on its way to perfection. The laity is given a more prominent role, and the local churches have been endowed with greater significance. Protestant churches regard church structures and ministry patterns as optional: the two determining indicators are the celebration of sacraments* and the preaching* of the gospel* with distinctive doctrinal and polity* emphasis according to the denominations; in practice, however, they increasingly function as voluntary associations. For independent* postdenominational churches, the determining factor for ecclesiality is the gathering of believers. While sacraments are celebrated and the Word preached, personal faith* is necessary. Believers’ baptism* makes the church a voluntary society; the church gathers “the called-out ones” (plausible etymology of ekklesia, though not emphasized in NT usages). Evangelism* and mission* are highly emphasized. Independent churches also insist on the separation between church and state. The biggest independent church movement, the Pentecostal*/ Charismatic* Movement, understands itself to be restorationist, with a desire to reclaim the charismatic life and worship of the apostolic church. The empowerment of all church members by the Holy Spirit is emphasized. Even when the Word is preached and hymns are sung, “encountering” the Lord is the aim, with signs following encounters, such as healings*. In the early 21st c the Christian Church is undergoing a transformation as its center of gravity moves rapidly from North to South, with the majority of church members residing outside Europe and North America. The Roman Catholic Church comprises one-half of all church members, Pentecostal/Charismatic and other independent churches a quarter, and Orthodox plus Reformation churches the remaining one-fourth. New challenges include, among others, the inclusion of women*, the questions of liberation* and equality, the promotion of the ministry (priesthood*) of all believers, and the acknowledgment of the missionary nature of the church. VELI-MATTI KÄRKKÄINEN Church, Concepts and Life: Feminist Perspectives. What are the terms of involvement of the female members of the church, anywhere in the world? To what extent are they free to speak, contribute, teach, preach, and lead? The fact that there are limitations for women reveals the inherent inequalities within the church structure, power, and leadership. Feminist concerns regarding the concept of “church” are tied to the understanding of the names for and nature of the Triune God*, by whom and for whom the church exists (see God, Christian Views of, Cluster: In North America: Feminist Understandings). Regarding church practice, feminists ask: Why are the voices of women considered less important or relevant than those of men? What are the implications for the church that its Scriptures* were written by – and primarily benefit – men? How can we counter the systemic neglect or dismissal of women (and other marginalized people) and their voices, perspectives, and contributions? It is not enough to pardon the past; past values and the structures and roles they created are still at work in our churches today. While some question whether “feminist” and “church” can coexist, the reality is that people are interested in making it so. Thus feminist voices and concerns need to be attended to by the church. JENNIFER BIRD Church, Concepts and Life: Names for the Church. The NT word for “church” is the Greek ekklesia, which was the common word used for an “assembly” of citizens and of people in a group. In the NT, ekklesia simply refers to an “assembly” of believers (the possible etymological meaning “the called-out ones” is not emphasized in the NT). The Syriac îdhtâ is very close in meaning to ekklesia, although it is also used for the building, along with hayklâ, a common word for palace or temple (with rich symbolism). Both the Greek ekklesia and the Latin ecclesia are also reflected in the Romance languages (chiesa, église, iglesia, igreja). The term gereja, used for “church” in Bahasa Malaysia and Bahasa Indonesia, comes from the Portuguese igreja. The German Kirche, Swedish kyrka, and English “church” are derived (through the Gothic) from the Greek kyriakon, signifying the “Lord’s house” or “community.” The Celtic domnach is similarly derived from the Latin dominicum, “domain” (of the Lord). There are many other names for “church” in various languages and related to particular cultures. The Romanian biserica comes from the Latin basilica. The Chichewa (Malawi) kachisi is the word originally used for African* Religion traditional shrines. The Chinese jiaohui, a term foreign to Chinese culture, was coined by missionaries, combining jiao (teaching or religion) and hui (an assembly of people or a place). Church, Concepts and Life: Types of Ecclesiastical Structures. When one considers the way in which authority* is exercised, one can distinguish five types of Christian churches. 1. Episcopalian (based on the NT references to bishops*). Authority is exercised within a hierarchy, with the bishop at the apex of the pyramid, as in the Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Orthodox churches, although they differ significantly. The Roman Catholic Church is highly centralized, with the pope* as the supreme head of a global organization (elected in a conclave of cardinals) and with Rome as the center of administrative authority. The Anglican Communion (including the Church of England) is much less centralized. It is organized in dioceses, each with a bishop, grouped in provinces, each with an archbishop (elected by both clergy and lay leaders), who presides over a synod deliberating on policy, ritual, and organizational matters of the Church but who does not have jurisdiction over dioceses other than his or her own. The Lambeth Conference of Anglican Bishops (in London, every 10 years since 1888) deliberates on matters of mutual concern, but with no juridical authority over bishops and dioceses; yet the consensus affirmed by its resolutions is authoritative. The Orthodox* churches, headed by patriarchs*, are organized in dioceses under bishops that function autonomously but in communion with each other. Autocephalous* Orthodox churches, such as the Russian Orthodox Church, are “self-headed,” with their own patriarchs and synods of bishops, an administrative independence that does not deny spiritual unity. 2. Presbyterian (based on the NT references to elders*). The Council of Elders (Presbyters) exercises church authority. From the local to the national level, there are layers of representation, culminating in the General Assembly, where policy decisions are made. The moderator of the General Assembly is elected for a limited period (one to five years). National Presbyterian churches, e.g. the Church of Scotland*, are held together in the World* Alliance of Reformed Churches. Though they have bishops, Lutheran churches (and their World* Lutheran Federation) and Methodist churches (and their World Methodist Council) nevertheless have chains of authority that are related to the Presbyterian type; the bishops’ authority is derived from and is exercised along with the representative body (synod or conference). 3. Congregational (based on the NT references to local churches functioning by consensus as the body of Christ; e.g. 1 Cor 12; Rom 12). Authority is vested in each specific congregation, which periodically “constitutes itself as a business meeting” to make decisions on the governance of all aspects of the church. The pastor is hired, dismissed, remunerated, and disciplined by the congregation. Baptist churches as well as those with the label “Congregational” belong to this group. 4. Charismatic Leadership (based on NT texts such as Acts 2; 1 Cor 12). In this model, despite those texts that emphasize the charismata* of all believers, authority is vested in a charismatic leader. When the leader loses charismatic power, the leadership role is immediately withdrawn and handed over to another leader in whom the congregation recognizes significant charismatic gifts. Many African* Instituted Churches (AICs) have this charismatic leadership structure and are associated with specific charismatic leaders or founders, e.g. the Deliverance Church and the Redeemed Gospel Church (Kenya), the Kimbanguist* Church (Democratic Republic of Congo), and the Church of Prophet Harris (West Africa). Many megachurches* in the USA, tropical Africa, Central America (e.g. Tabernaculo Biblico Bautista – Baptist Tabernacle, El Salvador), and South Korea also have this charismatic leadership structure. 5. Charismatic*/Pentecostal (based on NT texts such as Acts 2; 1 Cor 12). Authority emanates from the Holy Spirit and is vested in any believer who is moved by the Spirit and and receives charismatic gifts for the edification of the community. The Charismatic leadership is thus decentralized, counting on the Spirit-driven leadership of many of its members – who play important roles as leaders of cell groups – rather than that of a single leader. Such is the case of thousands of small Charismatic churches, and also of the biggest megachurches, such as Yoido Full Gospel (Seoul, South Korea) and Mision Elim Internacional (Ilabasco, El Salvador). These five types of ecclesiastical organization are based on NT patterns, although none actually replicate the apostolic church, because their organization reflects the cultural context in which they developed. The Roman Catholic Church places great importance on central authority not only because of NT models, but also because it took over imperial authority when the Roman Empire declined. Anglicanism was established in defiance of papal authority by King Henry VIII. The Church of Scotland adopted the Presbyterian polity*, in conformity with a nonhierarchical Scottish culture. Congregationalist churches flourish in individualist cultural settings (arising among the rising middle class in early-17th c. England, and spreading to North America). Charismatic leadership and CharismaticPentecostal churches are the most inculturated* – be they African Instituted Churches, US megachurches proclaiming a Prosperity* Gospel (see Word-Faith Movement, Its Theology and Worship), or Korean or Salvadoran megaCharismatic churches that call people to faithfully live the full gospel by expressing it in terms of elements of their cultural and religious heritage. See also Polity. JESSE NDWIGA KANYUA MUGAMBI X 2) A Sampling of Contextual Views and Practices Church, Concepts and Life: In African Instituted Churches. AICs are Christian bodies in Africa (c60 million members) “instituted” as a result of African “initiatives” in search of “independence” from missionary domination. Three types of AICs can be distinguished. Ethiopian churches, the earliest, originated in the 19thc. pan-African “Ethiopian Movement” (Ethiopia representing noncolonized Africa; Ps. 68:31); they emphasized African leadership, and thus “independence” from missionary churches, while keeping most of the theological views and practices of these churches. The much larger Zionist churches, with roots in US Pentecostalism, quickly had an exclusively African leadership and are more thoroughly inculturated*, drawing on African* Religion. Apostolic churches (or Prophetic churches) were and are “initiated” by Spirit-inspired African Apostles, such as Simon Kimbangu* in Congo* (from 1921), or John Maranke in Zimbabwe (from 1932). Today most AICs are independent and indigenous Charismatic* churches. They emphasize the importance of Spirit possession, dreams, visions, and speaking in tongues*; they practice healing* and exorcism* of evil spirits and other evil powers. Because of their inculturation (whether or not they practice polygamy* and African dietary taboos), AICs appeal to Africans through their interpretation of Scripture* (both OT and NT) and their worship using African symbols, music, and dance. TABONA SHOKO Church, Concepts and and Life: In Asia. The concept of “church” in Asia has been shaped by both external and internal factors, such as movements for national independence, the necessity of interreligious dialogue with neighbors of other religious traditions, and the ecumenical experience in the context of mission. The struggle for independence triggered a reconceptualization of the church as local and suffused by the cultural context. The May Fourth Movement and the socialist experience in China*, for example, led to the understanding of church as self-governing, self-propagating, and selfsupporting. The indigenous church movements in other parts of the continent moved in the same direction. The experience of Asian Christians with neighbors of other faiths has led to the realization of the church as a “community in dialogue*.” The Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences has turned dialogue into a key element for understanding the church in Asia, and according to it, the church fulfills its mission through a threefold dialogue with Asian religions*, Asian cultures*, and the Asian poor*. The minority situation in which almost all Asian churches find themselves (except in the Philippines*) has led them to a self-understanding of their life as that of a “little flock” (Luke 12:32) and their mission as that of salt and leaven (Matt 5:13, 13:33). This selfunderstanding of the church has served as a great force in overcoming the historically inherited division of churches and moving toward various kinds of ecumenical union. It is significant that in the context of mission the unified Church of South India (1947) was formed from three churches that are nowhere else in union. From a theological point of view, the understanding of church in Asia has been enriched by the institution of family* – so central to the Confucian* tradition – the experience of Buddhist* sangha (community) of equals, and the Hindu* concept of vasudevakudumbam (the family of the Lord). FELIX WILFRED Church, Concepts and Life: House Churches. See Chinese Contemporary Independent and House Churches. Church, Concepts and Life: In Latin America. The life of the Roman Catholic Church in present-day Latin America can be understood when one keeps in mind that it has gone through four periods: predominance of liberalism, populism, predominance of dictatorships, and openings toward democracy. Beginning in the late 19th c., the role of the Roman Catholic Church in colonial times was challenged by liberal governments and by Latin American societies influenced by modernization and laicization*; debates started in the press and in parliaments. The national states, economically liberal and politically conservative, sought to reduce the sphere of influence of the Church to private life. The life of the faithful tended to be limited to family, parish, and denominational schools. During this period, lay leaders gathered primarily to argue about the marginal role of the Church in the modern world. In the 1920s, the existing orientation toward social issues deepened. Social organizations, unions, and Catholic political parties were established more or less successfully in different countries, achieving a massive mobilization of lay Catholics as members of Catholic organizations – first Catholic* Action, then Specialized Catholic Action movements for youth, for university students, workers, and peasants; these movements provided opportunities for participation, formation, and social commitment. The radical commitment of lay Christian groups to sharing in the struggle of the poor*, the workers, and the often landless peasants led them to resist the bloody repression unleashed by the military dictatorships of Latin America starting in the 1960s, often supported by the Church hierarchy. The resulting breakup between hierarchy and laypeople of the Roman Catholic Church led to a long and difficult reorganization of the laity that began with the arrival of democracies. The democratic context favored the pluralization of the religious sphere. Different church groups – neo-Christian or para-Christian groups; Protestant* (or “Evangelical” in Latin American terminology), Charismatic* and Pentecostal* (in Latin America, the latter term is the inclusive designation for all Charismatics and Pentecostals), Native* American, and African* American churches, as well as Orientalist and New* Age groups – gained an unprecedented visibility starting in the 1980s. This pluralization is also found inside the Roman Catholic Church, with the rise of lay movements with different liturgical, doctrinal, and theological positions, relecting their various social milieus. All these movements within the Catholic Church are themselves quite diversified, and they include various groups of militants; yet their members remain deeply identified and committed to their movements, which occupy a growing position within the overall Roman Catholic Church and project with force their claims in the public sphere. VERÓNICA GIMÉNEZ BELIVEAU Church, Concepts and Life: In Latin America: Base Ecclesial Communities (CEBs) (Portuguese, Comunidades Eclesiais de Base). During the 1960s, a “communitarian wave” swept over the Roman* Catholic Church in Brazil, in reaction to the strictly institutional conception of the Church that predominated. This new conception of “church” entered Brazil through the Movement for a Better World and its teaching aimed at renewing pastoral practice along three axes: affirming the value of the laity* and the ministry of laypeople, decentralizing parish responsibilities (previously centered on the parish priest), and gathering authentic Christian communities characterized by faith, worship, and charity (social work). This ecclesiological ideal was widely welcomed in Brazil. It was implemented in some traditional ecclesial communities but developed beyond these after becoming an explicit objective of the 1966 United Pastoral Plan of the National Conference of Brazilian Bishops (CNBB) following the Second Vatican* Council. Base ecclesial communities became more independent in the 1970s, frequently connecting traditional communities (e.g. “rural chapels*”) with the action of all kinds of “modern pastors” (bishops, priests, sisters, laity formed for Catholic* Action, theologians, and sociologists). The CEBs are small groups, normally established in a neighborhood, slum, village, or rural zone, whose members regularly gather to pray, sing, celebrate, commemorate, read the Bible, and discuss it from the perspective of the life experience and struggles of that population. As Harvey Cox says, its objective is not to reconstruct the traditional communities (with their closed and authoritarian structures), but to bring about a new type of community that embodies the most important “modern freedoms.” The members of the communities cultivate a new relationship with the Holy One, by developing a new consciousness of the struggles of the people around them and a new ethical and political commitment to participate in their struggles. A CEB can be recognized by the following: (1) Sunday celebrations without a priest, (2) communitarian leadership, (3) biblical reflection groups, and (4) action aimed at transforming life in its context in partnership with social movements. See also Brazil; Roman Catholicism Cluster: In Latin America: various entries on Brazil. SÉRGIO COUTINHO Church, Concepts and Life: In Latin America: Ecuador: Base Ecclesial Communities (CEBs). Base Ecclesial Communities (Spanish, Comunidades Eclesiales de Base) are cell groups within the parish that make room for missionary laypeople and their creativity. Formed by families from neighborhoods in communion with the parish priest and the bishop, CEBs believe that the Roman Catholic Church is not merely the hierarchy or the institution. Faith guides CEBs as instruments for the transformation of culture*, for living out a prophetic stance by denouncing organized injustice and proclaiming a new hope for and with the poor*. CEBs promote the spirit of prayer, which is understood to be the key to conversion*. Although all members are facilitators, they work with leaders who are approved and qualified by the communitarian process to serve the CEB. CEBs started in the Riobamba Diocese (1962). At present, they are active in at least 10 ecclesiastical jurisdictions in Ecuador. There are also specialized groups called “Extension Teams of CEBs” (1985). CEBs are not juridically considered movements within the Roman Catholic Church, because their dynamics vary, depending on the families and communities involved. Although some fear them, CEBs have taken a position against “diseased apostolic fervor” that leads to sectarian cults rather than to a church as a communion of members. Indeed, CEBs see as part of their mission rediscovery of the Catholic Church. LUIS MARÍA GAVILANES DEL CASTILLO Church, Concepts and Life: In North America. The word “church” has three meanings in North America that reflect the operative conceptions of church in contemporary society. 1. The USA and Canada* have no official state religion. The term “church” is sometimes analytically paired with “state” (as in “church* and state”) to denote the relationship of all religious entities and belief groups to the state apparatus. In both societies, religious beliefs and associations are protected from governmental interference. Americans and Canadians highly value the separation of church and state, religious liberty, and the right of private judgment in moral matters. 2. “Church” also denotes a body of associated Christians who share ecclesiastical governance, on either a national or transnational basis. Thus Roman Catholics in North America refer to “the church” as the worldwide church headed by the pope; Presbyterians, Baptists, or Mennonites would typically use the same term to refer to their own denominations within a single nation. North American Christians often express concern about the church, by which they mean the chaotic organized life of Christian bodies above the level of local congregations. This phenomenon began in the 1960s; before that time, denominational expressions of Protestantism and national expressions of Catholic bodies were held in high esteem and collectively were remarkably effective in setting a religious tone for public and private morality without violating the principles of church–state separation. 3. By far the most common meaning of the word “church” in contemporary North America is that of a local congregation of believers. In contemporary North American culture, neither is one born into a church by law, nor does a territorial conception of parish* membership operate. Christians are accustomed to thinking of themselves first and foremost as members of a particular congregation, and refer to themselves as members, e.g., of St. Matthew’s Church or New Life Christian Fellowship. This local identification has come at the expense of enduring association with theological and ecclesial traditions. Thus in this mobile culture, people may choose to belong to a Lutheran Church in one location and join an Episcopal Church in another without ever identifying themselves as Lutheran or Anglican. While the clergy of the respective Christian traditions continue to be more associated theologically with the tenets of those expressions of faith, “church” for the laity has become increasingly a matter of a voluntary association with a particular gathered congregation. JAMES HUDNUT-BEUMLER Church, Concepts and Life: In Western European Theology. The Roman Catholic Hans Küng’s The Church (1967) elaborated on many key insights of Vatican* II’s Lumen Gentium, including the idea of the church as the people of God, church-inthe-making, work for the unity of the church, and the call to open up to society and world religions. The Reformed* Jürgen Moltmann’s The Church in the Power of the Spirit (1977) similarly advocated a participatory, nonhierarchic, charismatically structured, and open view of the church. In “relational ecclesiology,” the church never exists for itself but is always in relation to God and the world; therefore it is a serving, missionary church. Both Küng and Moltmann underline the charismatic* structure of the church and the charismata/charisms* of its members. For Moltmann the church is a “charismatic fellowship” of equal persons, without division between office bearers and people. Moltmann’s ecclesiology searches for equality and justice among church members and also among all men and women. The Triune God as a society of equals is the model. While a hierarchical notion of the Trinity* leads to a hierarchical view of the church, an open Trinity enhances openness, mutual respect, and loyalty. Building on the biblical and patristic tradition, the Greek Orthodox John Zizioulas’s Being as Communion (1985) argues that all true personal existence happens in relationality, communion. Even the mode of the existence of the Triune God is relational. Thus becoming Christian means a move from “biological individualism” to an “ecclesial personhood.” Communion ecclesiology soon established its place as an ecumenical conviction across denominational borders. The Croatian Miroslav Volf entered the most foundational debate in contemporary ecclesiology: What is the ecclesiality of the church? What makes the church, church? The extreme views are represented by catholic churches (Roman and Eastern) and free or independent* churches. Unlike the former, independent churches do not require a bishop (or a priest ordained by a bishop) to ensure the presence of Christ; the presence of Christ is “ensured by faith response” apart from any officers. In the Roman Catholic tradition, Christ’s presence is mediated sacramentally*, and the bishop or priest is needed to preside over the Eucharist; by contrast, independent churches speak of Christ’s unmediated, “direct” presence in the entire local communion. Volf’s own “ecumenical” free church view holds that while Christ’s presence cannot be tied to either offices or sacraments (catholic churches), the mediation of faith is also not individualistic or absolutely unmediated. The mediation of faith happens in the community, via tradition and all church members, and not merely via ordained persons. For faith to be personal, there must be a genuine appropriation of the faith of the church. The former missionary bishop Lesslie Newbigin has been a key voice in developing the emerging ecumenical idea of the church’s missionary nature. Rather than being one of the tasks of the church, mission* is the very being of the church. When the church takes seriously its faith in the gospel as “public truth,” mission flows out of its confident, yet humble and respectful sharing of the good news to all people. The flip side of the “logic of mission” is that the church that keeps the good news for itself compromises its own being as the bearer of the gospel. For Newbigin the missionary church by its very nature advocates the unity of the church. The Lutheran Wolfhart Pannenberg’s Systematic Theology, which includes a significant ecumenical ecclesiology of contemporary times, argues that unless the church reconciles its divisions, it has little hope of convincing the world and other religions of the supremacy of the gospel. VELIMATTI KÄRKKÄINEN