file - EBF Groningen

advertisement

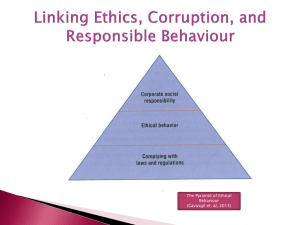

IBS – Mike Kruijer Chapter 1: Multinational strategy Strategic planning is the process of evaluating an enterprise’s environment and internal strengths, identifying its basic mission and long-and short-range objectives, and implementing a plan of action for attaining these goals. MNEs rely heavily on this process because it provides them with both general direction and specific guidance in carrying out their activities. With strategic planning, research shows that many MNEs have been able to make adjustments in their approach to dealing with competitive situations and either redirect their efforts or exploit new areas of opportunity. MNEs have strategic predispositions toward doing things in a particular way: - Ethnocentric: An MNE will rely on the values and interests of the parent company in formulating and implementing the strategic plan. Polycentric: An MNE will tailor its strategic plan to meet the needs of the local culture. Regiocentric: An MNE will use a strategy that allows it to address both local and regional needs. Geocentric: An MNEW will view operations on a global basis. Strategy formulation is the process of evaluating an enterprise’s environment and internal strengths. The analysis of the external environment involves two activities: information gathering and information assessment. Information can be gathered by asking industry experts, using historical trends to forecast future developments, asking knowledgeable managers to write scenarios, and using computers to simulate the industry environment. Such information helps MNEs to identify competitor’s strengths and weaknesses and to target areas for attack. The information is assessed based on the five forces that determine industry competitiveness: bargaining power of suppliers, bargaining power of buyers, threat of new entrants (reduce by keeping costs low and loyalty high, lobby), threat of substitutes (low prices, similar products, increase services), and rivalry among competitors (offer new goods, increase productivity differentiate, increase quality, target niches). Environmental assessment is used to determine MNE opportunities and threats and help identifying strategies for improving market position and profitability. The internal environmental assessment helps pinpoint MNE strengths and weaknesses. A multinational should examine the physical resources and personnel competencies and the way in which value chain analysis can be used to bring these resources together in the most synergistic and profitable manner. The physical resources are the assets that the MNE will use to carry out its strategic plan, in which the location and disposition of these resources is also important. Another important consideration is the degree of integration that exists within the operating units of the MNE. Large companies tend to be divided into strategic business units (SBUs), being operating units with their own strategic space and have a well-defined set of competitors. Moreover, some firms use vertical integration, which is the ownership of all assets needed to produce the goods and services delivered to the consumer. This may reduce costs, but can also lead to inefficiencies. Virtual integration is the ownership of the core technologies and manufacturing capabilities needed to produce outputs coupled with dependence on outsources to provide all other needed inputs. Personnel competencies are the abilities and talents of people. A complementary approach to internal environment assessment is an examination of the firm’s value chain. A value chain is the way in which primary and support activities are combined to provide goods and services and increase profit margins. AN MNE can use the primary and support activities to increase the value of the goods and services they provide. Analysis of the value chain can also help a company determine its generic strategy: cost, differentiation, and focus. External and internal environmental analyses provide an MNE with the information needed for setting goals. Strategic implementation is the process of attaining goals by using the organization structure to execute the formulated strategy properly. Three of the most important areas in this process are location, ownership decisions, and functional area implementation. Location facilities often provide a cost advantage to the producer and residents may prefer locally produced goods. Furthermore, an MNE can either form a SA of IJV. A strategic alliance is an agreement between two or more competitive MNEs for the purpose of cooperating in some manner. An international Joint Venture is an agreement between two or more partners to own and control and overseas business and typically involves setting up a new business entity. Reasons for JV are government encouragement and knowledgeable local partners, though joint ventures are difficult to manage and are frequently unstable. The strategy formulation and implementation processes are subject to control and evaluation. Common measures are return on investment, sales growth/market share, costs, product development, host-country relations, and overall management performance. ROI brings advantages in showing a single comprehensive result, measures globally, and allowing a comparison. However, it does not take into account transferring products internally, can be misleading in quickly growing markets, and is a short-term measure of performance. Chapter 2 – Hierarchical modes One entry mode is the hierarchical mode, where the firm completely owns and controls the foreign entry mode. The degree of control that head office can exert on the subsidiary will depend on how many and which value chain functions can be transferred to the market. There are multiple hierarchical modes A domestic-based sales representative is one who resides in one country, often the home country of the employer, and travels abroad to perform the sales function. As the sales representative is a company employee, better control of sales activities can be achieved than with independent intermediaries, which is likely to lead to more commitment to the customer. With resident sales representatives, the sales function is transferred to the foreign market, showing greater customer commitment. The decision to use a domestic-based or resident sales representative is based on whether it is order making or order taking and the nature of the product (technical product or not?). A foreign branch is an extension and a legal part of the firm and employs nationals of the country as sales-people. If foreign market sales develop in a positive direction, the firm might consider a foreign subsidiary, which is a local company owned and operated by a foreign company under the laws of the host country. One of the major reasons for choosing sales subsidiaries is the possibility of transferring greater autonomy and responsibility to these subunits, being close to the customers and the fact that it may lead to tax advantages. When the company believes that its products have long-term market potential, then full ownership of sales and production will provide the level of control to meet the firm’s strategic objectives fully. However, this entry mode requires great investment in terms of management time, commitment and money, together with high levels of risk. The main reasons for establishing some kind of local production are to defend existing business, gain new business, save costs, and to avoid government restrictions. Setting up an assembly operation is another option and is usually a result of multisourcing. Subsidiaries can employ four strategies to enhance their strategic position: - - - Seize the initiative and growing the subsidiary autonomy: Subsidiaries can try and gain more autonomy, allowing it to act more freely on opportunities. Build information networks to external partners: The assigned market leads to an absence of real market response which inhibits market initiative and innovation, cutting off the potential to develop and drive the next generation of products. Therefore, a subsidiary should build its own external links, so it can broaden its market and seek new perspectives on the future. Create a climate for entrepreneurship: subsidiaries should create a climate which encourages risk-taking and focus on the long-term. Integrating measures of longer term objectives within short-term goals and including non-financial measures of performance will promote management efforts at building a sustainable future, such as directing resources at identified market opportunities. Promote subsidiary strategy development: subsidiaries can actively engage in subsidiary strategy development. It can win future investment by competing with other subsidiaries over the MNCs investments. Geographically focused start-ups (region centers) can serve the specialized needs of a particular region, since it will play the role of coordinating and stimulating sales in a whole region. This gives the company the chance to respond to regional needs and to move downstream (or the whole value chain) activities to the region centre. Formation of region centres implies creation of a regional HQ or appointment of a ‘lead country’, which will play the role of coordinator and stimulator. The coordinator role consists of ensuring country and business strategies are mutually coherent, one subsidiary does not harm the other, and adequate synergies are fully identified and exploited across business and countries. The stimulator role consists of facilitating the translation of local products into local country strategies, and supporting local subsidiaries in their development. The choice of lead country is influence by the marketing competences of the foreign subsidiaries, the quality of human resources in the represented countries, the strategic importance of the countries represented, the location of production, and the legal restrictions of host countries. Common R&D and frequent geographical exchange of human resources across borders are among the characteristics of a transnational organization. Its overall goal will be to achieve global competitiveness through recognizing cross-border market similarities and differences, and linking the capabilities of the organization across national boundaries. In deciding to establish wholly owned operations in a country, a firm can either acquire an existing company or build its own operations from scratch. Acquisition enables rapid entry and often provides access to distribution channels, an existing customer base, and sometimes established brand names or corporate reputations. This may be particularly advantageous for a firm with limited international management expertise or familiarity with the local market. Acquisitions can be horizontal, vertical, concentric, or conglomerate. Greenfield investments have the advantage that you do not have to integrate with another company, which means a fresh start and an opportunity to shape the local firm into the company’s own image and requirements. Strategic motives that can affect the HQ location decision are mergers and acquisitions (new neutral location), internationalization of leadership and ownership, and strategic renewal. Closing down a subsidiary or selling it off to another firm can also be strategic decisions a firm makes. The incentives can be profits that are too low, expropriation, lack of growth, lack of strategic fit, high cultural distance, an incompetent partner company, or result from gaining new experience that tells you to shut the subsidiary down. Chapter 4 – Innovation in a global world Globalization involves a convergence of tastes and product preferences, integration of purchasing, manufacturing, and marketing, globally operated organizations, and markets and industries which are dominated by a few large players. The process of industry globalization is influenced by a number of drivers, which can be grouped into market, cost, economic and governmental, and competitive drivers. Market factors driving globalization are: homogenous customer need (desire for same product/service), global customers (customers buy globally), global channels (global distribution), and transferable marketing (unique brand value requires little local adaptation) Important cost drivers for globalization are economies of scale and scope, learning and experience, sourcing efficiency, favorable logistics (introduction of free technology for flowers), and technology development costs (recouping investments requires a global market). Government policies can influence a globalised approach by means of trade policies, integration of the capital markets, global binding rules of law, and compatible technical standards. Finally, competitive drivers can result from globalizing competitors and interdependence of countries (close monitoring by other countries of your products) Though not all scholars agree on the globalization matter, there is a growing body of evidence indicating that many markets are becoming increasingly international or global in their nature. More demanding consumers pressure organizations to be flexible and responsive, leading to the development of notions such as a global strategy and transnational strategy. Following the product life cycle theory, the starting point of internationalization is typically an innovation in the home country. The second stage, in which the home market becomes saturated, involves the innovating firm looking to develop exports in similar markets. The third stage is characterized by product standardization and the arrival of competitors, leading to a focus on cost competitiveness. In the final stage, the developing nations may become net exporters to developing regions, since they move there to cut the costs of (for example) labor. As a company grows, it becomes necessary to introduce structures capable of achieving coordination and integration of geographically disperse operations. The pattern of change depends on the diversity of the company’s product range and the relative amount of foreign sales. Firms can choose to go for setting up and international division (in case of low sales, low product range), setting up a geographic division (large market, low diversity). Development along either path eventually culminates in a global matrix structure, which is able to provide benefits of local responsiveness and product-based economies through appointing a manager for every product and area. Multi-national firms manage their innovation by organizing and controlling their operations through different organizational formats: - Ethnocentric centralized R&D: This organization is one in which R&D activity is concentrated in the home nation and one in which the company adopts the stance that - - - - the home country centre is superior in technology and knowledge. It lacks sensitivity to emerging demands and trends and is often plagued by the not-invented-here syndrome. This configuration is commonly deployed by companies entering newly emerging markets. Geocentric centralized R&D (centralized hub): This model overcomes some homecountry focus problems by attempting to recruit a more multi-cultural, multi-national workforce, while engaging in listening activities in external markets and maintaining efficiency advantages of a centralized innovation and knowledge base. Polycentric decentralized R&D (decentralized federation): With this configuration, the centre provides investment to set up subsidiaries, which operate as independent fully integrated business units with considerable autonomy. This allows for local responsiveness, but often entails little exchange of knowledge between units, which might lead to duplication of effort. R&D hub model (co-ordinated federation) This form is characterized by a strong central R&D home base supported by R&D outposts. Tight central control and coordination of R&D is provided by the centre. The integrated R&D network. In this form, each unit specializes and leads in a particular product, technology, or function, while being interconnected with other units. Here, R&D investment is intensive, but the fruits of a unit’s R&D labor can be exploited by others in the network, leading to problems of taxation and transfer prices. The pressures from the forces of globalization necessitate that companies simultaneously optimize efficiency and local responsiveness, and learn, pushing a company to a transnational form. Managers operating in global environments must be able to reconcile interdependence of functions with different geographies and coordinate the overall activities to build and sustain competitive advantage. This requires a multi-dimensional approach, one that allows tasks to be differentiated by allowing different areas to be treated and organized differently, relationships to be based on interdependence, and coordination of sub-units through a shared vision and development of integrative mechanisms. The multi-dimensional approach leads to the development of an integrated network which represents the transnational form. The integrated network possesses three key elements: - - - Multi-dimensional perspectives, which requires developing capabilities to respond to local needs, developing competitive capabilities on a global level, and processing competitive capabilities to create and leverage new competencies through innovation and facilitate their transfer amongst other units Distributed and interdependent capabilities. The company becomes an integrated network of distributed, yet interdependent, capabilities working to the benefit of the whole organization Flexible integrative process. Processes that facilitate integration are centralization, formalization, and socialization. History shows that it is difficult to form this kind of a company. Most often, companies fall into either the centre for global innovation model or the local for local innovation model. To make central innovations effective, the company needs to gain the input of subsidiaries into centralized activities, respond to local-national needs (while pushing for central control, you have to ensure that the local market is not ignored), and manage responsibility-personnel flow (rotate to ensure cross-functional integration). To make local innovation efficient, one should empower local management, link local managers to corporate decision-making processes, and force tight inter-functional integration. What activities the firm focuses on (e.g., R&D and innovation) depends on a firm’s specific advantage, whereas the location of the activity depends on the firm’s comparative advantage. Moreover, the international environment differs from the domestic environment along institutional and cultural difference, and factor costs. Two key factors can affect the neat ordering of the chain of comparative advantage (the fact that developed nations are good in R&D, and developing nations in labour intensive activities), being the cost of transportation and tariffs, and firm-specific competitive advantages. Once the decision about R&D location has been taken, the task of managing innovation in a multinational company remains. Barlett and Ghoshal defined four primary types of subsidiaries: strategic leader (High importance, high competence of local organization), Contributor (Low importance, high competence of local organization), Implementer (Low, Low), and Black Hole (High importance, low competence) Culturally diverse environments demand culturally sensitive management. Team diversity brings different skills and distinct knowledge, but should be managed by stimulating communication and cultivating trust. Progress in doing so can be impeded by large physical distance between team members. This problem can be solved by implementing virtual teams (though they fail more often than succeed). Global business managers have to play the following roles in order to secure global economies of scale and leverage worldwide market positions: worldwide business strategist, architect of asset and resource configuration, and cross-border coordinator(ensure flow of information). Worldwide functional managers need to be worldwide-intelligence scanner, cross-pollinator of best practices, and champions of transnational innovation. Geographic subsidiary managers need to be bi-cultural interpreters, national defenders and advocates, and front-line implementers of corporate strategy. Finally, top-level corporate managers should provide direction and purpose, leverage corporate performance, ensure the flow of resources, and ensure continual renewal of the firm. Chapter 5 – Strategic Alliances A strategic alliance exists whenever two or more independent organizations cooperate in the development, manufacture, or sale of products of services. SAs can be grouped into nonequity alliances (work together, but take no equity position in each other) such as licensing agreements, supply agreements, and distribution agreements, and equity alliances (take equity position). Furthermore, in a joint venture, cooperating firms create a legally independent firm in which they invest and from which they share any profit that is created. Strategic alliances create value by exploiting opportunities and neutralizing threats facing a firm. Opportunities can be found in three categories. First, alliances can improve the performance of current operations (exploiting economies of scale, learning from competitors (winning the learning race), sharing risks and costs). Second, alliances can be used to create a competitive environment favorable to superior firm performance (setting technology standards in network industries, explicit/tacit collusion). Finally, alliances can be used to facilitate a firm’s entry or exit from new markets or industries. Entry into an industry can require skills, abilities, and products that a potential entrant does not possess. SAs can help a firm enter a new industry by avoiding the high costs of creating these skills, abilities, and products. Firms often have difficulty in obtaining the full economic value of their assets as they exit and industry. By forming an alliance with a firm that may want to purchase its assets, a firm is giving its partner an opportunity to directly observe how valuable those assets are. Finally, firms may use SAs to manage uncertainty, as they will enable a firm to maintain a point of entry into a market or industry without incurring the costs associated with full-scale entry. There are also incentives to cheat on SA agreements. Cheating can occur in three different ways: - - Adverse selection: Potential partners misrepresent the value of the skills and abilities they bring to the alliance. In general, the less tangible the resources and capabilities that are bound to a strategic alliance, the more costly it will be to estimate their value before an alliance is created, and the more likely it is that adverse selection will occur. Moral hazard: Partners provide to the alliance skills and abilities of lower quality than promised. Holdup: When one firm makes more transaction-specific investments in a SA than partner firms make, that firm may be subject to the form of cheating called Holdup, in which partners exploit the transaction-specific investments made by others in the alliance. For a strategic alliance to be a source of sustained competitive advantage, it must be rare and costly to imitate. If a low-cost substitute is available, a competitive advantage will not be sustained. Substitutes are ‘going it alone’ and acquisitions. Firms go it alone when they attempt to develop all the resources and capabilities they need to exploit market opportunities and neutralize market threats. Alliances will be preferred over going it alone when the level of transaction-specific investment is moderate, an exchange partner possesses valuable, rare, and costly to imitate resources and capabilities, and there is great uncertainty about the future value of an exchange. Alliances will be preferred to acquisitions when there are legal constraints on acquisitions, acquisitions limit a firm’s flexibility, there is substantial unwanted baggage in an acquired firm, or the value of a firm’s resources and capabilities depends on its independence. A variety of tools and mechanisms can be used to help realize the value of alliances and minimize the threat of cheating. These include contracts, equity investments, firm reputations, joint ventures, and trust. Chapter 6 – Ethics and International Business Ethics are moral principles and values that govern the behavior of people, firms, and governments regarding right and wrong. Simply obeying the law is usually insufficient to ensure against violating fundamental standards of ethical behavior. As a result, most advanced firms emphasize corporate social responsibility and sustainability next to ethical behavior. Corporate social responsibility means operating a business in a manner that meets or exceeds the ethical, legal, and commercial expectations of all stakeholders, whereas sustainability means meeting humanity’s need without harming future generations. An integrated, strategic approach to ethical behavior provides firms with competitive advantages, including stronger relationships with all stakeholders. Intellectual property rights are the legal claims through which the proprietary assets of firms and individuals are protected from unauthorized use by other parties. Trademarks, copyrights, and patents are example of those proprietary assets. Behaving ethically is important for several reasons. First, it is the right thing to do. Second, it is often prescribed within laws and regulations. Third, ethical behavior is demanded by stakeholders. Finally, ethical behavior is good business, leading to enhanced corporate image and selling prospects. Ethical standards vary around the world. There are two perspectives to this. First, relativism is the belief that ethical truths are not absolute but differ from group to group (when in Rome, do as the Romans do).By contract, normativism is the belief that ethical behavioral standards are universal and firms and individuals should seek to uphold them consistently around the world. As with ethical behavior, there is a strong business case for CSR. CSR is simply the right thing to do and it helps the firm recruit and retain high-quality employees, as it improves employee perception of the firm. Moreover, strong CSR can help the firm differentiate itself in the marketplace and enhance its brand. And CSR is a factor in cutting the costs of business. Finally, CSR helps the firm avoid increased taxation, regulation, or other legal actions by the local government authorities. A sustainable business simultaneously pursues three types of interests: economic interests, social interests, and environmental interests. Corporate governance is the system of procedures and processes by which corporations are managed, directed, and controlled. It provides the means through which firms undertake ethical behaviors, CSR, and sustainability. There are five standards that managers can use to examine ethical dilemmas: - Utilitarian approach: The best action is the one that provides the most good or does the least harm. Rights approach: The action that best protects and respects the moral rights of everyone involved is the best. Fairness approach: Everyone should be treated equally and fairly. Common good approach: Actions should be based on the welfare of the entire community or nation. Virtue approach. Ethical actions should be consistent with certain ideal virtues that provide for the full development of humanity. Making ethical decision follows a four step framework. First, the ethical problem needs to be recognized, after which you have to get the facts. The next thing is to evaluate alternative courses of action, after which the decision has to be implemented and evaluated. Chapter 8 – Government intervention in international business Governments intervene in trade and investment to achieve political, social, or economic objectives. Government intervention is often motivated by protectionism, which refers to national economic policies designed to restrict free trade and protect domestic industries from foreign competition. Protectionism is often manifested by tariffs, nontarrif barriers such as quotas, and arbitrary administrative rules. Protected environments may lead to fewer incentives to improve quality, design, and overall product appeal. Moreover, it can lead to price inflation because tariffs can restrict the supply of a particular product. Government intervention can be the result of a desire to generate substantial revenue for the government, desire to ensure the safety, security, and welfare of citizens, pursue economic, political, or social objectives, and serve the interest of the nations firms and industries. The rationale of trade and investment barriers can be considered to be either defensive or offensive. Governments impose defensive barriers to safeguard industries, workers, and special interest groups and to promote national security (protection of the national economy, protection of an infant industry, national security, and national culture and identity). Governments impose offensive barriers to pursue strategic or public policy objectives, such as increasing employment or generating tax revenues (National Strategic Priorities, Increasing Employment). There are multiple instruments of government intervention. Check out Exhibit 8.2 to see the different types, their definition and effects. Subsidies are monetary or other resources that a government grants to a firm or group of firms, intended either to encourage exports or simply to facilitate the production and marketing of products and reduced priced, to help ensure the involved companies prosper. Governments sometimes retaliate against subsidies by imposing countervailing duties, which are tariffs on products imported into a country to offset subsidies given to producers or exporters in the exporting country. Subsidies may allow a manufacturer to practice dumping, that is, to charge an unusually low price for exported products. Governments can reply to this dumping by imposing an antidumping duty (tax). Firms can respond to government intervention by performing research to gather knowledge and intelligence, choose the most appropriate entry strategy, take advantage of foreign trade zones, seek favorable customs classifications for exported products, take advantage of investment incentives and other government support programs, and lobby for freer trade and investment.