supporting critical conversations in classrooms

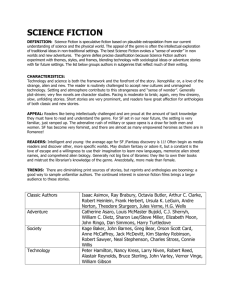

advertisement