ACRES Creative Writing The Adult College for Rural East Sussex

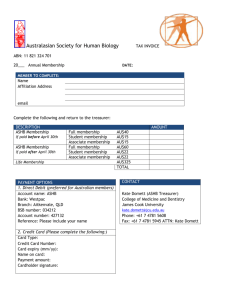

advertisement