File - I`m An Organ Donor, Are You?

advertisement

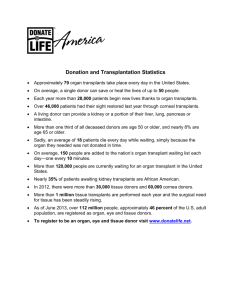

Running Head: ORGAN DONATION 1 Organ Donation Uncovering Systems around the World Aubree Malone First Colonial High School ORGAN DONATION 2 Abstract This paper will outline and explain different rules, regulations, and laws followed by different countries around the world as they pertain to organ donation or anatomical gifts. Several different donation systems will be discussed as the countries chosen all have different donation systems in place to try to accommodate the needs of the people. The countries discussed in this paper are Russia, Iran, and the United States. Since the United States of America is broken up into 50 states which all have different laws regarding anatomical gifts, three states will be discussed: Arkansas, Hawaii, and Virginia. These three states show the diverse laws within one country pertaining to the same concept. One state outlines the least regulations and benefits for donors, one state is moderate, and the last state has many regulations and benefits for their donors. ORGAN DONATION 3 Organ Donation: Uncovering Systems around the World In the United States of America, 18 people die each day awaiting an organ transplant (“Why Organ,” n.d.), one tragedy that could be solved if more people were educated about the processes of organ donation. Some countries require education, some have developed systems to obtain organs without permission from the donor, and some offer financial benefits to increase their organ supply. Nonetheless every country has laws regarding anatomical gifts to try and regulate/increase the amount of organs in their organ supply. One donor could save up to eight lives and aid over 50, but there are not enough life saving organs in circulation to save everyone. Due to the need for organs exceeding the amount of organs available, many laws and transplant systems have been put in place to try to reduce the margin between the sick and the organ supply. History Throughout time, organ donation has been a debated topic, only thought to save the lives of people who were closely related (twins and/or fraternal twins), but that turned out not to be the case at all, seeing as there could be a match for a person whom is not related to the patient. Organ donation is considered a life saving practice. Throughout time medical physicians have pushed the limits with organ donation from the first successful [renal] transplant in 1954 between a pair of twins to, creating a complex allocation system to distribute out harvested organs from deceased patients (UNOS.org) in 1986 (“Why Organ,” n.d.). In a short amount of time, medical professionals tested their limits with transplanting organs then brought it worldwide, to save the lives of millions. Now that the practice has been set in stone to save lives, each country (and its states) tries to gather more organs to put into circulation to save more lives. ORGAN DONATION 4 The downfall to this whole operation is the world’s population is growing, increasing the margin between the organ supply and the amount of organs needed. As the donation system becomes more efficient and reliable, fewer donors come forth. With fewer donors, desperation opens up for organs spurring the thought for revised donation systems, to fit the needs of the people in that country. Some donation systems are more equipped to the citizens, but others are put in place by the country’s government just to shade the real issue at hand. [American] Statistics Donors are separated into two categories: living donors, and deceased donors. Of course more organs come from dead donors because more can be harvested from their bodies, but living donors are a huge source for renal (kidney) anatomical gifts. People of every age donate organs from even the youngest (one year old), “260 (241 deceased, 19 living donors),” (“Why Organ...,” n.d.) to the eldest of the society (65 and up), “5,070 (4,271 deceased, 799 living donors),” (“Why Organ…,” n.d.). See appendix A for full statistics. Even though donors come from every age range, there are not enough in circulation to fulfill the number of lifesaving organs that are needed to save every ill person. The number of donors has increased since the start of the practice, but looking at recent years (1991 – 2013) these efforts are parallel with a growing population of people in need. In 1991 the difference between donors and was 16,245: 6,953 donors and 23,198 on the waiting list. In 2013 the margin has sharply increased with the difference between donors and patients on the waiting list being 107,015: 14,257 donors and 121,272 on the waiting list. Between 1991 and 2013, the number of donors has only increased by 7,304 while the number of patients on the waiting list ORGAN DONATION 5 has increased by 98,074 (“Why Organ…,” n.d.). See appendix A for full statistics and a graph showing the relationship between donors, transplants, and number of people on the waiting list. American Transplant System Allocation (UNOS.org) Allocation is the process in which organs are distributed to people in need. Allocation starts at the local level from wherever the organs were harvested, then spans outwards to find an appropriate candidate. This process allows for a fair and efficient distribution of the organs donated. Allocation is run through a system called United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). UNOS maintains a centralized computer network, UNetSM, which links all organ procurement organizations (OPOs) and transplant centers. Transplant professionals can access this computer network 24 hours a day, seven days a week. UNet electronically links all transplant hospitals and OPOs in a secure, real-time environment using the Internet (“UNOS DonateLife,” n.d.). UNOS also owns and operates the transplant waiting list which is maintained by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The OPTN was created when the National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA) was passed through Congress (“UNOS DonateLife,” n.d.). Laws, Rules, and Regulations (adopted in America) Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (UAGA) All of the states follow the rules and regulations set forth by the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act (UAGA), but not all the states follow the same version. The versions range from 1968 in Delaware, to the latest version in 2013 followed by Oregon. Each version has the same basic ORGAN DONATION 6 concepts, but each is revised to accommodate more modern needs in the organ donation system. Before the UAGA was passed, states handled their own system of organ donation. The 1968 UAGA was the first legislation put into place to regulate organ and tissue donations and was accepted throughout all 50 states. Its sole purpose in 1968 “was to increase the number of available organs for transplant by making it easier for people to make anatomical gifts,” (“Legislative,” n.d.) but through generations, the law was adapted to fit the needs of the country. The UAGA was set in place to try and unify all the states to have around the same organ donation practices. The most common version followed by the states is the 2006 version which tried “…to provide uniformity in state laws regarding organ and tissue donation. Additionally, there were huge strides in the technology and practice of donation and transplantation since the last revision” (“Legislative,” n.d.). The UAGA is one of the most important pieces of legislation regarding organ donation practices. Dead Donor Law The Dead Donor Law states that vital organs should only be harvested from brain dead patients. Brain death is classified as “Irreversible brain damage and loss of brain function, as evidenced by cessation of breathing and other vital reflexes, unresponsiveness to stimuli, absence of muscle activity, and a flat electroencephalogram for a specific length of time” (“Brain Death, n.d.). All states follow some form of the Dead Donor Law. Even if not explicitly said in state’s statutes, two doctors will declare a person “dead” when all brain function has ceased. Two doctors with a witness are required to declare a person as deceased, so that action cannot be brought against doctors for wrongly declaring a patient as deceased. After the patient has been declared deceased and the family has been notified, only then will vital organs be harvested from the deceased patient. ORGAN DONATION 7 National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA) “In 1984, Congress passed the National Organ Transplant Act that mandated the establishment of the OPTN and Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients. The purpose of the OPTN is to improve the effectiveness of the nation's organ procurement, donation and transplantation system by increasing the availability of and access to donor organs for patients with end-stage organ failure. The Act stipulated that the network be a nonprofit, private sector entity whose members are all U.S. transplant centers, organ procurement organizations and histocompatibility laboratories. These members, along with professional and voluntary healthcare organizations and the representatives of the general public, are governed by a Board of Directors. The OPTN is administered by UNOS under contract to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services” (“Why Organ…,” n.d.). NOTA also outlawed the sale of organs in the United States of America. NOTA, along with the UAGA, are the most important legislation put in place to regulation donation practices. State Laws Each state within the United States of America has different laws regarding anatomical gifts and organ donation. States range from having the first version of the UAGA created in 1968 governing their organ donation practices, to the most recent version in 2013. Each state offers different benefits for living donors or none at all. Some states require education about anatomical gifts in school while others do not. Also the source of revenue for each state’s practices differ from voluntary donations to state provided funds. Each state is unique in how they regulate their organ donation practices (“Why Organ…,” n.d.). The one uniform protocol ORGAN DONATION 8 that every state must maintain is their donor registries. These registries are the easiest way to find out if the deceased wished to donate his/her organs, eyes, and/or tissues. Donor Registries - A confidential electronic database in which individuals can enter and store their wish to be an organ and tissue donor. Most registries are for a single state, but a few serve more than one state. Most registries have enrollment capacity through the motor vehicle offices and many also have online registry portals. Because registry information is accessible on a 24/7 basis to authorized procurement personnel, it is the safest and quickest way to determine if a deceased individual wanted to be a donor. (“Why Organ…,” n.d.). Donor registries expedite the allocation system because they offer a faster harvest to obtain the organs, so they can be distributed to people in need. Registries also place less serious decision making on the mourning family. If the decedent has already applied to be an organ donor, this leaves that decision out of their family’s hands. Many families say this is such a hard decision without the decedent there. The families do not want to disrespect their lived one’s body if, when they were living, the decedent did not wish to be a donor. Arkansas. Arkansas provides the most support for living donors including benefits like tax breaks. The benefits are also accompanied by education in school and driver’s education for the youth, which leads to more donors. Arkansas receives voluntary contributions and state provided funds toward their organ donation practices. Arkansas follows the 2006 version of the UAGA which was enacted to try and unify the 50 states in regard to their donation practices, and was also enacted to try and strengthen the livelong decision of becoming a donor (“Why Organ…,” n.d.). The 2006 UAGA also offered new technology to strengthen the system and ORGAN DONATION 9 adapted regulations regarding the person who can make the decision on donation on behalf of the decedent (“Why Organ…,” n.d.). Virginia. Virginia is considered a moderate state when it comes to organ donation. Virginia requires education about anatomical gifts in only driver’s education. Virginia has limited support for living donors which does not include tax breaks like in Arkansas. Virginia does not provide state funds for donation practices, but does accept voluntary contributions. Along with Arkansas, Virginia follows the 2006 version of the UAGA to regulate their organ donation (“Why Organ…,” n.d.). Hawaii. Hawaii offers the least support and education for donors. Organ donation in Hawaii is very minimal. Hawaii offers no support or benefits for living donors. Also, Hawaii does not require education in either school or driver’s education about anatomical gifts. Along with no support and no education, the state does not provide funds for these practices and leave it up to the people to contribute. As well as Virginia and Arkansas, Hawaii follows the 2006 version of the UAGA (“Why Organ…,” n.d.). 2006 UAGA. Arkansas, Virginia, and Hawaii, though extremely different in their organ donation practices, all follow the same version of the UAGA which sets the basis for their anatomical gift processes. The 2006 UAGA can be revised or adapted to the state’s own needs, but in the case of these three states the UAGA adopted in each, sets forth the same regulation. In the layout of the UAGA for each state their own state codes are included, but for the understanding, the state codes have been removed and replaced with [state code] so that just the basic outline of the 2006 UAGA is shown. ORGAN DONATION 10 [state code]. Preclusive effect of anatomical gift, amendment, or revocation. A. Except as otherwise provided in subsection G and subject to subsection F, in the absence of an express, contrary indication by the donor, a person other than the donor is barred from making, amending, or revoking an anatomical gift of a donor's body or part if the donor made an anatomical gift of the donor's body or part under [state code] or an amendment to an anatomical gift of the donor's body or part under [state code]. B. A donor's revocation of an anatomical gift of the donor's body or part under [state code] is not a refusal and does not bar another person specified in [state code] or [state code] from making an anatomical gift of the donor's body or part under [state code] or [state code]. C. If a person other than the donor makes an unrevoked anatomical gift of the donor's body or part under [state code] or an amendment to an anatomical gift of the donor's body or part under [state code], another person may not make, amend, or revoke the gift of the donor's body or part under [state code]. D. A revocation of an anatomical gift of a donor's body or part under [state code] by a person other than the donor does not bar another person from making an anatomical gift of the body or part under [state code] or [state code]. E. In the absence of an express, contrary indication by the donor or other person authorized to make an anatomical gift under [state code], an anatomical gift of a part is neither a refusal to give another part nor a limitation on the making of an anatomical gift of another part at a later time by the donor or another person. ORGAN DONATION 11 F. In the absence of an express, contrary indication by the donor or other person authorized to make an anatomical gift under [state code], an anatomical gift of a part for one or more of the purposes set forth in [state code] is not a limitation on the making of an anatomical gift of the part for any of the other purposes by the donor or any other person under [state code]. G. If a donor who is an unemancipated minor dies, a parent of the donor who is reasonably available may revoke or amend an anatomical gift of the donor's body or part. H. If an unemancipated minor who signed a refusal dies, a parent of the minor who is reasonably available may revoke the minor's refusal. (2006). Case Law Schembre v. Mid-America Transplant Ass'n On November 28, 1998, appellant’s husband passed away due to a fatal heart attack. Shortly after the death of the decedent, the family (decedent’s wife and two [adult] children) were approached by a member of the hospital staff, Guelbert. Guelbert informed the family that the decedent did not meet requirements for organ donation, but was eligible for donation of his eyes, bone, and tissue. The initial decision was not to allow the donation, but after appellant talked to her children, they decided the decedent’s wish to help others justified donations. Appellant wanted only to allow donation of decedent’s corneas and wanted to restrict all other donations. Guelbert then talked about bone donation, which he showed the amount using his hands, inquiring that it would be a two to four inch section removed from the leg bone above the ORGAN DONATION 12 knee. Appellant had more questions, but were not able to be answered by Guelbert (Schembre v. Mid-America Transplant Ass'n, 2004). Guelbert testified that the appellant and her children were in favor of organ donation. Guelbert also testified that he thoroughly explained the donation process. He said he explained that if bone and eye donation was chosen, the full leg bone and eye would be removed from the decedent’s body (Schembre v. Mid-America Transplant Ass'n, 2004). After discussion, Guelbert aided appellant with the consent form, which indicated the parts being donated. Both Guelbert and appellant went through the form and checked “yes” for bone and eye donation, and “no” for tissue donation. Even though Guelbert went step by step through the form, appellant did not actually read the consent form on account of being “too distraught from her husband’s death.” Appellant wanted to limit the donations from decedent’s body, but on the face of the consent form there were no limitations. Upon completion Guelbert passed the form over to Mathew Thompson. Thompson states he saw no discrepancies within the consent form, and did not further contact the family (which follows protocol). Thompson called the tissue recovery team from MTS, who performed the harvest. The MTS team removed all lower leg bone, and the entire eye for the removal of the corneas. The family was informed of the removal of the entirety of both eye balls, and the full removal of leg bone from the lower leg region, after decedent’s body was released for funeral preparation (Schembre v. Mid-America Transplant Ass'n, 2004). The issue in the case is whether the MTS recovery team acted in good faith regarding recovery of bones and corneas, or was the MTS teams negligent in the removal of leg bone and corneas from decedent’s body? ORGAN DONATION 13 UAGA Section 194.270.3 RSMo (1996), adopted and modified in Missouri states: “[a] person who acts without negligence and in good faith and in accord with the terms of this act or with anatomical gift laws of another state or foreign country is not liable for damages in any civil action or subject to prosecution in any criminal proceeding for his [or her] act,” (1996). Florida UAGA used as precedent [because Missouri laws did not exactly fit facts of the case] states: FN2. Fla. Stat. Section 765.517(5)(2002) states “A person who acts in good faith and without negligence in accord with the terms of this part ... is not liable for damages in any civil action or subject to prosecution for his or her acts in any criminal proceedings,” (2002). In order for the appellant to prove negligence against the defendant, appellant must prove that the defendant breached a duty which directly resulted in the injury of the appellant. There is no dispute that MTS has a duty to follow the requirements set forth under the UAGA in order to complete a valid organ donation. MTS first obtained a written consent form which is permissible under Section 194.240.2. The form was executed by a member of a class of persons authorized to consent to organ donation pursuant to Section 194.220.2(2). MTS presented testimony that the consent form appeared to be valid on its face with no limitations noted. Additionally, MTS offered evidence of its standard protocol when removing the eyes, bone, and tissue and testified that it followed these protocols. Finally, no one from Decedent's family contacted MTS to limit or revoke the gift which would preclude it from accepting the gift as mandated in Section 194.220.3. ORGAN DONATION 14 There is no evidence in the record creating a genuine issue of material fact that MTS breached its duty in the instant case. Therefore, we hold MTS acted without negligence when removing Decedent's corneas, bone, and tissue (Schembre v. Mid-America Transplant Ass'n, 2004). The court ruled in favor of the Mid-America Transplant Association. Thompson followed protocol by checking over the consent formed signed by appellant. Thompson did not see any signs of discrepancies, so no further contact to the family was made. The MTS team acted in good faith without negligence by following rules and regulations set forth by the UAGA. The MTS team only removed parts specified on the consent form without limitations. The appellant and the family did not contact the MTS team to set forth and limitations or revoke the anatomical gifts (Schembre v. Mid-America Transplant Ass'n, 2004). Lawse v. University of Iowa Hospitals On August 15, 1973, a kidney was harvested from Steve Lawse’s body in order to be transplanted into his brother Paul’s body. Lawse was informed that he could live with only kidney, and was informed after his surgery that one kidney had been removed. One year later, Paul’s graft failed, and then Paul was given a cadaver transplant. Paul died years later. Lawse’s remaining kidney failed on January 23, 1984. Lawse then received a transplant from an unrelated donor (Lawse v. University of Iowa Hospitals, 1988). “On May 7, 1985, plaintiff filed an administrative claim with the State Appeals Board pursuant to Iowa Code section 25A.5 (1987)” (Lawse v. University of Iowa Hospitals, 1988). Lawse’s claim regarded the removal of his kidney and the treatment since the surgery for the removal. Lawse claims that he was not psychologically competent enough to donate one of his ORGAN DONATION 15 kidneys, and he did not understand the suffering he would endure after the removal. Lawse claims the defendants were negligent in that they disregarded his unwillingness to donate, and they coerced Lawse to donate his kidney to his brother. The issue in the case is whether the removal of Lawse’s kidney was wrongful, in that the patient was not properly informed about the risk of the removal of one of his kidneys. The other issue is should Lawse’s claim be barred due to the statute of limitations? The two laws looked at most in this case are Iowa Code section 25A.5 (1987) regarding the period in which a client can bring up a claim, and Iowa Code section 614.1(9) (1987) which explains the statute limitations on medical malpractice (Lawse v. University of Iowa Hospitals, 1988). Iowa Code section 25A.5 (1987) states: Every claim and suit permitted under [the state tort claims act] shall be forever barred, unless within two years after such claim accrued, the claim is made in writing to the state appeal board under this chapter. The time to begin suit under this chapter shall be extended for a period of six months from the date of mailing of notice to the claimant by the state appeal board as to the final disposition of the claim or from the date of withdrawal of the claim from the state appeal board under section 25A.5, if the time to begin suit would otherwise expire before the end of such period. If a claim is made under any other law of this state and a determination is made by a state agency or court that this chapter provides the exclusive remedy for the claim, the time to make a claim and to begin suit under this chapter shall be extended for a period of six months from the date of the court order making such determination by a state agency, if the time to make the claim and to begin the suit under this chapter would otherwise expire before the end of such period. (1987) [law has been revised since its passing] ORGAN DONATION 16 Iowa Code section 614.1(9) (1987) states: Malpractice. Those founded on injuries to the person or wrongful death against any physician and surgeon, osteopath, osteopathic physician and surgeon, dentist, podiatric physician, optometrist, pharmacist, chiropractor, physician assistant, or nurse, licensed under chapter 147, or a hospital licensed under chapter 135B, arising out of patient care, within two years after the date on which the claimant knew, or through the use of reasonable diligence should have known, or received notice in writing of the existence of, the injury or death for which damages are sought in the action, whichever of the dates occurs first, but in no event shall any action be brought more than six years after the date on which occurred the act or omission or occurrence alleged in the action to have been the cause of the injury or death unless a foreign object unintentionally left in the body caused the injury or death (1987). Lawse’s claims of wrongful removal allege that the doctor assured him that: (1) Paul would die without his kidney when in fact his brother was doing well on dialysis, (2) there was basically no risk to him, it was like having an appendix removed; but he should stay away from horses due to the risks if he should injure his remaining kidney, and (3) he was the best match. He also contends: (1) he was not told his older brother had refused to donate his kidney, (2) other family members were told he was a match before he was, (3) he was given limited information, and (4) he was under duress (Lawse v. University of Iowa Hospitals, 1988). In the case Lawse v. University of Iowa Hospitals, the issue comes about that Lawse did not claim any negligence until he needed his harvested kidney. No one could have predicted that ORGAN DONATION 17 he would need that kidney or a transplanted kidney in the future, but the surgery that harvested his kidney to transplant to his brother, was not the direct cause of his reaming kidney to fail. While sudden coercion may have happened by the physicians stating that a close relative will die without the donation, it does not justify the claims of wrongful removal and psychological damage. Lawse’s claim was barred due to the six year statute of limitations. Which means since the claim was not filed within six years the case was disqualified (Lawse v. University of Iowa Hospitals, 1988). Sale of Organs The open market for organs has been a debated topic in many countries for a long time. It is seen as a way to entice more donors, with financial compensation, to donate their organs. Without the open market crime happens and with an open market, crime happens. Both situations pose the same outcome with crime; however, the reasoning for said crime is different with each issue. Without the sale, anatomical gifts are seen as a way to make quick money to compensate immediate financial needs and with the sale, organs may be too expensive to purchase for middle or low class citizens, so they turn to the black market for more affordable organs. “Cash for Kidneys” Canadians have been juggling the idea of “cash for kidneys.” Medical professionals feel as though if they give out financial support to those who donate their kidneys then it will increase the amount of organs in circulation. 18 people die each day waiting for a lifesaving organ (Why Organ,” n.d.). Canadians are willing to look more into the sale of organs because as of right now it is illegal for certain ethical reasons. Canada has seen an increasing decline in the ORGAN DONATION 18 amount of registered donors, so without organ donors Canada cannot harvest needed organs. Canada’s transplant list becomes longer and longer increasing the wait time for each organ. Some patients have seen a wait time of over a decade, but have only been given weeks to live. People are given hope then die before they can receive their lifesaving organ. Studies show that people would be able to part with their organs if that had a financial incentive. For example, receiving 1,000+ dollars for donating a kidney while still living, or giving financial support like covering funeral costs, to families with a deceased loved one that gave up their organ (Komarnicki, 2012). The “cash for kidneys” movement is gaining momentum because saving more lives feels right to everyone. Crime The black market has sped itself up in countries in Europe. People are looking to sell their kidneys for financial compensation. A man with two children says it is just a small sacrifice he has to make to feed his children (Bilefsky, 2012). The black market is definitely not something that will ever abate especially with the aid of the internet. People post their organ ads and wait for the highest bidder. Selling their organs is a way to get fast money to cope with their financial problems. Obviously with these organ ads, people are thinking very irrationally and do not think about future consequences and the burden this could potentially place on their family. Their surgery could put further another load on their family than just the financial issue. In their desperation they do not think about if the deal is genuine, or if they will get scammed or even killed for their organs. This phenomenon is dangerous and with the legalization of the open market could get worse. Organs could become too expensive with the open organ market, and people will turn to the black market to buy cheaper organs and cheaper expenses on surgery that may, in turn, not be safe (Bilefsky, 2012). ORGAN DONATION 19 But the crime doesn’t stop there; it spreads itself around the world creating a blanket operation in which people, wherever, they are in the world, can sell their body parts for money. In Australia, many families who are having trouble conceiving are learning that they can have a baby within a year if they are willing to pay the right price, $10,000 - $50,000. Though this practice is illegal in Australia, some will never stop striving for what they think they deserve. Many poor women, like in Thailand, sell their eggs to people like this, but medical officials fear that these women are lying about their medical history so they can gain money. The money that the donors receive usually depends on the woman’s looks. One big provider to this illegal market for eggs, are college women from the United States. These women could get paid $10,000 or more, for her each egg she donates because the looks of these women are well sought after (Baker, 2012). Like the other women who donate, these college students are trying to make ends meet within their financial situations. In other countries, women give up their eggs to put food on the table for their children or family, but with many more desperate women from these third world countries, their eggs are not wanted, so they are paid much less than the rare American donor(Baker, 2012) . Immoral reasons for donation The piece of the organ market talked about in this section of the paper is the open market for living donors that donate their kidneys for financial benefit. The sale of organs can lead to immoral reasons for donating. Donation should be a moral obligation, not a way to make money. With the sale, many people will see it as just a way to make money. The reason the sale is even considered a moral system within some countries is because it creates more organs in circulation that will, in turn, save many lives. Part of the argument is that people do immoral things all the time for no reason, with this, at least the turn out, is a saved life. ORGAN DONATION 20 Iranian Transplant System Iranians undertook the financial benefit system of organ donation, which is essentially selling organs for money. Within Iran living donors can donate their kidneys for financial compensation. In the 1980s many countries frowned upon handing out money for donation practices and passed laws outlawing the sale, as seen in the United States when NOTA was passed. Some countries do not see anything wrong with financial compensation for lifesaving organs. After careful evaluation Iran adopted the renal financial incentive form of organ donation of 1988. Iran’s amount of renal donations sharply increased since this adoption, which then lead to the eradication of the renal transplant list in 1999. With this system in place, Iran performs more renal transplants from living-unrelated donors than from deceased donors (Ghods & Savaj, n.d.). “By the end of 2005, a total of 19,609 renal transplants were performed (3421 from living related, 15,356 from living-unrelated and 823 from deceased donors)” (Ghods & Savaj, n.d.). With the growing number of patients with end stage renal failure needing a kidney transplant, many countries are looking to develop a new system to increase the number of kidneys in circulation (while still avoiding financial incentives for donation), but none of the proposed systems will completely eradicate the waiting list, like as seen in the Iran model (Ghods & Savaj, n.d.). Financial Benefit As stated before, many countries during the 1980s passed legislation regarding the sale of organs. Many countries outlawed the sale, but some after careful consideration decided that with financial incentives the citizens within their country would be more willing to donate their organs or donate the organs of their deceased loved ones. Sometimes the human race just needs ORGAN DONATION 21 a little push to do something nice for others. The biggest issue in the medical community with giving out financial incentives for organs is that it could lead to unethical transplant practices. As long as the donation practice is closely regulated, the unethical practices should not come about (Ghods & Savaj, n.d.). Russian Transplant System The Russian transplant system is based off of a policy derived from the Soviet Union in the time of the Cold War. After the Cold War, Russians lost trust in their government, which led to a severe decrease in organ donations/transplants. Then when “command form organ donation” was adopted from the Soviet medical System, it rendered a negative response from the public as it was seen to violate the rights of the deceased individuals (“Transplant coordination in Russia,” n.d). Implied Consent “Implied consent” or “command form organ donation” means that a person is automatically assumed to be an organ donor upon the time of their death (“Transplant coordination in Russia,” n.d). The relatives of said person have no say in the matter. One of the main reasons countries do not adopt the implied consent system, is because it can be considered disrespectful to the decedent’s body. There are so many reasons why people are not organ donors some of which are considered religious reasons, so assuming that a person is an organ donor, without their or their family’s consent, could violate the rights of that person. Silence does not mean yes; only yes gives consent. So with the implied consent system, there will be organs harvested from people who did not wish to be organ donors, which ultimately sets up ORGAN DONATION 22 little trust. If a country’s government constantly disrespects its people, it will soon lose all power. Conclusion Though the organ supply is not sufficient enough to help every person in need, the systems put in place in different countries are beginning ideas towards a solution. Practices in both Iran and Russia are highly debated because they both pose ethical questions. Even though The United States’ system is considered the most ethical because all donations are voluntary, their system does not offer a practical solution to the organ shortage problem because without a sufficient amount of donors, not all the sick will receive the lifesaving organs they need. No one wants an innocent life to be taken, so these systems presented are only to help save the people. Although ethical issues are present in some of these systems, they all lead to the same positive solution: thousands of saved lives. Taking into account the positives and negatives of each system, saved lives will always trump the negative outcomes. ORGAN DONATION 23 References Advisory Committee on organ transplantation. (n.d.). Retrieved May 6, 2014, from http://organdonor.gov/legislation/acotsummaryrec.html Arizona Anatomical Gift Law. (n.d.). Retrieved December 14, 2014, from http://uniformacts.uslegal.com/anatomical-gifts-act/arizona-anatomical-gift-law/ Baker, J. (2012 sep 30). Life as we know it. Sunday Telegraph (Surry Hills), p. P. 42. Retrieved May 6, 2014, from http://sks.sirs.com Bilefsky, D. (2012 jun 29). Black Market for body parts spreads among the poor in Europe. New York Times, p. A.8. Retrieved May 6, 2014, from http://sks.sirs.com Brain death. (n.d.). Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http://medicaldictionary.thefreedictionary.com/brain+death Evanisko, M. J., Beasley, C. L., Brigham, L. E., Capossela, C., & Al, E. (1998, January). Readiness of critical care physicians and nurses to handle requests for organ donation. American Journal of Critical Care, 7(1), 4-12. Retrieved October 7, 2014, from ProQuest Career and Technical Education; ProQuest Psychology Journals; ProQuest Science Journals. Florida UAGA statute, § 765.517 (2002). Ghods, A. J., & Savaj, S. (n.d.). Iranian model of paid and regulated living-unrelated kidney donation. Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http%3A%2F%2Fcjasn.asnjournals.org%2Fcontent%2F1%2F6%2F1136.full Hawaii Organ Donation - Info on Donating Organs in HI. (1999). Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http://www.dmv.org/hi-hawaii/organ-donor.php ORGAN DONATION 24 Hawaii Statutes - Revised UNIFORM: ANATOMICAL GIFT ACT. (n.d.). Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http://codes.lp.findlaw.com/histatutes/1/19/327/UNIFORM International survey of nephrologists' perceptions and attitudes about rewards and compensations for kidney donation. (n.d.). Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http://ndt.oxfordjournals.org/content/28/6/1610.full.pdf+html Iowa Code, § 25A.5 (1987). Iowa Code, § 614.1(9 (1987). Iowa Code 142C. (n.d.). Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http://coolice.legis.iowa.gov/CoolICE/default.asp?category=billinfo&service=IowaCode&ga=83&input=142C Johnson, B. (2014, April 21). Gift of life Michigan sues Saginaw County medical examiner over handling of 6-year-old Elijah Dillard's organs. Retrieved May 6, 2014, from http://www.mlive.com/news/saginaw/index.ssf/2014/04/gift_of_life_michigan_sue_sagi. html Komarnicki, J. (2012 sep 28). 'Cash For Kidneys' gaining acceptance. Calgary Herald, p. P. A.1. Retrieved May 6, 2014, from http://sks.sirs.com Lawse v. University of Iowa Hospitals (Court of Appeals of Iowa. November 29, 1988). Legislative. (n.d.). Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http://www.aopo.org/legislative Lin, S. S., 0-Rich, L., Pal, J. D., & Sade, R. M. (0005, December 01). Introduction Robert M. Sade, MD. Retrieved May 6, 2014, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3388804/ LIS Code of Virginia. (n.d.). Retrieved December 1, 2014, from https://leg1.state.va.us/cgibin/legp504.exe?000+cod+TOC32010000008000000000000 Malone, M. L. (2014, November 25). Anatomical gifts [Personal interview]. ORGAN DONATION 25 Mardfin, J. K. (1908). Heart and soul: Anatomical gifts for Hawaii's transplant community. Honolulu, HI: Legislative Reference Bureau. Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http://lrbhawaii.info/lrbrpts/98/soul.pdf Ogilvie, J. P. (2011 mar 28). A kidney market at what cost? Los Angeles Times, p. E.1. Retrieved May 6, 2014, from http://sks.sirs.com Organ donation in Hawaii: Impact of the final rule. (n.d.). Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12010140 Patient protection and affordable care act; exchange and insurance market standards. (2014, May 14). Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Regulations-and-Guidance/Downloads/508CMS-9949-F-OFR-Version-5-16-14.pdf Preclusive effect of anatomical gift, amendment, or revocation., Pub. L. No. UAGA (2006). Satel, S. (2011 dec 06). A lifesaving legal ruling on organ donation. Wall Street Journal, p. A.13. Retrieved May 6, 2014, from http://sks.sirs.com Satel, S. (2013 jun 12). Dying children shouldn't have to beg for organs. Usa Today, p. P. A.6. Retrieved May 6, 2014, from http://sks.sirs.com Schembre v. Mid-America Transplant Ass'n (Missouri Court of Appeals, Eastern District, Division One. May 11, 2004). Silva, D., & Connor, T. (2013, November 14). NBC News - Breaking news & top stories - Latest World, US & local news. Retrieved May 6, 2014, from http://www.nbcnews.com/#/news/other/death-row-organ-donations-pose-practicalethical-hurdles-f2D11595275 ORGAN DONATION Transplant coordination in Russia: First experience. (n.d.). Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18555103 UAGA adopted in Missouri, § 194.270.3 (1996). UNOS DonateLife. (1986). Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http://www.unos.org/ UNOS DonateLife. (n.d.). Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http://www.unos.org/donation/index.php?topic=organ_allocation Why Organ, Eye, and Tissue Donation? (n.d.). Retrieved December 1, 2014, from http://www.organdonor.gov/index.html 26 ORGAN DONATION 27 Appendix A American Statistics All information, charts, and pictures were derived from organdonor.gov People of every age give and receive organ donations. In 2013, 28,953 people received organ transplants. Below is the number of recipients by age group followed by the number who received organs from deceased and living donors: 1 Year Old: 260 (241 deceased, 19 living donors) 1 - 5 Years: 545 (437 deceased, 108 living donors) 6 - 10 Years: 292 (228 deceased, 64 living donors) 11 - 17 Years: 721 (591 deceased, 130 living donors) 18 - 34 Years: 3,081 (1,983 deceased, 1,098 living donors) 35 - 49 Years: 6,310 (4,699 deceased, 1.611 living donors) 50 - 64 Years: 12,674 (10,516 deceased, 2,158 living donors) 65+ Years: 5,070 (4,271 deceased, 799 living donors) As of December 4, 2012, the percentage of recipients who were still living 5-years after their transplant is noted below for kidney, heart, liver, and lung. Kidney (deceased donor): 83.4% Kidney (living donor): 92% ORGAN DONATION Heart: 76.8% Liver (deceased donor): 74.3% Liver (living donor): 81.3% Lung: 55.2% In 1991, there were 6,953 Donors, 15,756 Transplants, and 23,198 Waiting list In 1992, there were 7,091 Donors, 16,134 Transplants, and 27,563 Waiting list In 1993, there were 7,766 Donors, 17,631 Transplants, and 31,355 Waiting list In 1994, there were 8,203 Donors, 18,298 Transplants, and 35,271 Waiting list In 1995, there were 8,859 Donors, 19,396 Transplants, and 41,203 Waiting list In 1996, there were 9,222 Donors, 19,765 Transplants, and 46,961 Waiting list In 1997, there were 9,545 Donors, 20,314 Transplants, and 53,167 Waiting list In 1998, there were 10,362 Donors, 21,523 Transplants, and 60,381 Waiting list In 1999, there were 10,869 Donors, 22,026 Transplants, and 67,224 Waiting list In 2000, there were 11,934 Donors, 23,266 Transplants, and 74,078 Waiting list In 2001, there were 12,702 Donors, 24,239 Transplants, and 79,524 Waiting list In 2002, there were 12,821 Donors, 24,910 Transplants, and 80,790 Waiting list In 2003, there were 13,285 Donors, 25,473 Transplants, and 83,731 Waiting list In 2004, there were 14,154 Donors, 27,040 Transplants, and 87,146 Waiting list In 2005, there were 14,497 Donors, 28,118 Transplants, and 90,526 Waiting list In 2006, there were 14,750 Donors, 28,940 Transplants, and 94,441 Waiting list In 2007, there were 14,400 Donors, 28,366 Transplants, and 97,670 Waiting list 28 ORGAN DONATION In 2008, there were 14,207 Donors, 27,964 Transplants, and 100,775 Waiting list In 2009, there were 14,631 Donors, 28,458 Transplants, and 105,567 Waiting list In 2010, there were 14,504 Donors, 28,662 Transplants, and 110,375 Waiting list In 2011, there were 14,149 Donors, 28,539 Transplants, and 112,816 Waiting list In 2012, there were 14,011 Donors, 28,054 Transplants, and 117,040 Waiting list In 2013, there were 14,257 Donors, 28,954 Transplants, and 121,272 Waiting list 29