Signal Processor Analysis (2) - Electrical and Computer Engineering

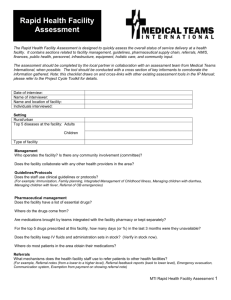

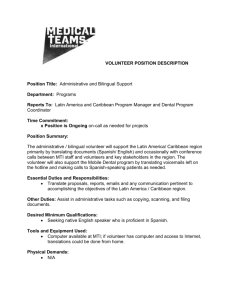

advertisement