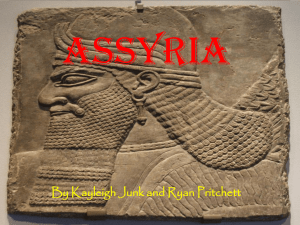

Ashurbanipal

advertisement

Ashurbanipal From ABC-CLIO's World History: Ancient and Medieval Eras website http://ancienthistory.abc-clio.com/ Known as the last of the great kings of ancient Assyria, Ashurbanipal was renowned for his patronage of the great library of Nineveh. Appreciative of preserving the writings of his culture, as well as those of his neighbors, he sent subjects of his kingdom throughout the region in search of authentic works and created the first catalogued library in the Near East. Known to the Greeks as Sardanapalus and in the Hebrew Bible as Asnappeer, Ashurbanipal was born during the seventh century BCE to the Assyrian king Esarhaddon. His father's kingdom was extensive; it reached from Egypt in the west to the Persian Gulf in the east. In May 672 BCE, Esarhaddon appointed Ashurbanipal as the crown prince of Assyria, and it was in that position that he learned the statecraft that would serve him well throughout his reign. Ashurbanipal boldly believed that he needed to be a literate and well-educated leader in order to manage his domains. His passion for knowledge led him to learn to read and write the Sumerian and Akkadian scripts; he also mastered the sacred knowledge of the ancient Assyrian religion and much secular knowledge. He was well trained in martial arts, hunting, horsemanship, and archery, and he was renowned for his dynamic personality, too. Those qualities made Ashurbanipal a charismatic and successful contender for assuming the throne on his father's death in December 669. Already well informed about affairs of state, Ashurbanipal declared himself king, and the rest of the court accepted his declaration. Throughout his reign, Ashurbanipal focused on three major projects: subduing rebellion in his territories; the expansion of religion in society; and being a patron of scholars and artists. The first problem was especially serious on his ascension to the throne. When Esarhaddon died, the Egyptian pharaoh Taharqa sparked a rebellion against Assyrian rule there. Ashurbanipal's troops were able to suppress the uprising quickly; that demonstrated to Assyria's conquered subjects that the new king would be a stable and powerful force. He installed Necho I as supreme ruler, which was in keeping with his promise to maintain native rule. Although Ashurbanipal would lose Egypt to Psamtik I, trade relations were good, and he was able to maintain strength in the region. Ashurbanipal then went on to send troops to reassert Assyrian power over Tyre, Lydia, and the rest of Syria, as well as Ur and Babylon. Esarhaddon had appointed Ashurbanipal's half brother, Shamash-shum-ukin, to the position of crown prince of Babylon. When he became king, Ashurbanipal allowed his half brother to maintain that position, although he restricted Shamash-shum-ukin's powers over military control. For over a decade, Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin appeared to have good relations. However, after disagreements over the way Babylon was to be ruled, Shamash-shum-ukin launched a plot to overthrow Ashurbanipal. Shamash-shumukin made secret alliances with the local leaders of Egypt, Lydia, Phoenicia, Judah, Nabataea, and Elam, as well as a variety of Chaldean tribes. His plan was to rebel against Assyrian rule simultaneously—forcing Ashurbanipal to lose power. The Assyrians were faced with subduing those rebellions, but Ashurbanipal was victorious. In 648, Shamash-shum-ukin committed suicide. Despite the overall victory of the Assyrians, small rebellions continued throughout the empire until 639, when Ashurbanipal finally declared his empire to be stable. That stability allowed him to focus on his other pursuits. Ashurbanipal was an ardent patron of the arts and especially fond of sponsoring dramatic architecture and sculpture. He was also deeply religious and saw to the restoration of the most important shrines of his kingdom. For Ashurbanipal, it was important that the gods were aware of the piety of his family, and he and his wife, Ashur-sharrat, were often seen leading ceremonies and sacrifices publicly. The greatest contribution of Ashurbanipal's reign, however, was undoubtedly his extensive library at Nineveh, which is considered by modern practitioners of library science to be the first systematically organized library in the Near East. At its height, the library contained more than 30,000 cuneiform tablets, and when it was rediscovered in 1849, at least 1,200 of the original 5,000 literary texts were recovered near present-day Mosul, Iraq. Most of the holdings were moved to the British Museum in London, but a significant portion remained in Iraq, where they were ultimately held by the Iraqi Department of Antiquities in Baghdad. Sadly, it is believed that many of those treasures were lost during the violent events of the Iraq War in 2003. Ashurbanipal took personal control over the library, which became an incredible reserve for ancient knowledge. He sent his scribes throughout his kingdom to collect and copy the important Sumerian and Akkadian texts of the region, both holy texts from the temples and secular works from scientists, lawmakers, and astrologers. Some of those works include the Epic of Gilgamesh and the Code of Hammurabi, as well as folktales, spells, poetry, recipes, and dictionaries. Ashurbanipal also maintained his government records in the library, which essentially created an archive that has provided scholars with priceless information about his reign. The building of the library became a crucial factor in the organization of the collection. Ashurbanipal had his librarians organize the holdings by designating special rooms for specific topics. The innermost room of the library held the secret archive of his government, and most of those documents remained classified. One of the most striking aspects of the documents that remain from that library was that many, both official and unofficial, as well as sacred and secular, bear signs that they were from Ashurbanipal's personal collection. It is clear that he took a very personal interest in that library and considered it to be one of his most important accomplishments. Despite such attention to cataloging detail, Ashurbanipal's death date remains unknown; most historians place it ca. 627 BCE. Scholars do know that before his death, Ashurbanipal declared his sons Ashur-etel-ilani and Sin-shar-ishkun as the coregents of Assyria and Babylonia. Despite that vague information about his final years, Ashurbanipal's legacy as the inspiration behind one of the ancient world's most important houses of knowledge solidified his importance to world history. MLA: Stockdale, Nancy. "Ashurbanipal." World History: Ancient and Medieval Eras. ABC-CLIO, 2014. Web. 6 Jan. 2014.