Diseases of the Immune System lec.3

Diseases of the Immune System lec.3

2014-2015

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

AIDS is a retroviral disease caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). It is characterized by infection and depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes, and by profound immunosuppression leading to opportunistic infections, secondary neoplasms, and neurologic manifestations.

Pathogenesis of AIDS

HIV disease begins with acute infection, which is only partly controlled by the host immune response, and advances to chronic progressive infection of peripheral lymphoid tissues.

The first cell types to be infected may be memory CD4+ T-cells in mucosal lymphoid tissues. Because the mucosal tissues are the largest reservoir of T-cells in the body and a major site of residence of memory T cells, the death of these cells results in considerable depletion of lymphocytes.

The transition from the acute phase to a chronic phase of infection is characterized by dissemination of the virus, viremia, and the development of host immune responses. DCs in epithelia at sites of virus entry capture the virus and then migrate into the lymph nodes. Once in lymphoid tissues, DCs may pass HIV on to CD4+ T- cells through direct cell–cell contact.

Within days after the first exposure to HIV, viral replication can be detected in the lymph nodes. This replication leads to viremia, during which high numbers of HIV particles are present in the patient’s blood, accompanied by an acute HIV syndrome that includes a variety of nonspecific signs and symptoms typical of many viral diseases.

The virus disseminates throughout the body and infects helper T cells, macrophages, and DCs in peripheral lymphoid tissues. As the infection spreads, the immune system mounts both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses directed at viral antigens. These immune responses partially control the infection and viral production, and such control is reflected by a drop in viremia to low but detectable levels by about 12 weeks after the primary exposure.

1

Diseases of the Immune System lec.3

2014-2015

In the next, chronic phase of the disease, lymph nodes and the spleen are sites of continuous HIV replication and cell destruction. During this period of the disease, the immune system remains competent at handling most infections with opportunistic microbes, and few or no clinical manifestations of the HIV infection are present. Therefore, this phase of HIV disease is called the clinical latency period.

Although a majority of peripheral blood T cells do not harbor the virus, destruction of CD4+ T- cells within lymphoid tissues steadily progresses during the latent period, and the number of circulating blood CD4+ T- cells steadily decline , until reaching the crisis phase.

Mechanisms of T- Cell Depletion in HIV Infection

1.

The major mechanism of loss of CD4+ T- cells is lytic HIV infection of the cells, and cell death during viral replication and production of virions.

2.

Loss of immature precursors of CD4+ T- cells, either by direct infection of thymic progenitor cells or by infection of accessory cells that secrete cytokines essential for CD4+ T- cell maturation. The result is decreased production of mature CD4+ T cells.

3.

Chronic activation of uninfected cells by HIV antigens or by other concurrent infectious microbes may lead to apoptosis of the T cells. Because of this

“activation induced death” of uninfected cells.

4.

Fusion of infected and uninfected CD4+ T- cells may be killed by HIVspecific CD8+ CTLs.

5.

Qualitative defects in T-cell function that can be detected even in asymptomatic HIV infected persons. Such defects include reduced antigen induced T-cell proliferation, impaired TH1 cytokine production, and abnormal intracellular signaling.

6.

Selective loss of memory CD4+ T cells early in the course of the disease, possibly related to the abundance of these cells in mucosal tissues.

Monocytes/Macrophages in HIV Infection

Similar to T -cells, most of the HIV-infected macrophages are found in the tissues and not in peripheral blood. Infected macrophages bud relatively small amounts of

2

Diseases of the Immune System lec.3

2014-2015 virus from the cell surface but contain large numbers of virus particles located in intracellular vesicles. In contrast with CD4+ T-cells, macrophages are quite resistant to the cytopathic effects of HIV and can, therefore, harbor the virus for long periods.

Thus, macrophages are the gatekeepers of HIV infection. Besides providing a portal for initial transmission, monocytes and macrophages are viral reservoirs and factories, whose output remains largely protected from host defenses. Circulating monocytes also provide a vehicle for HIV transport to various parts of the body, particularly the nervous system. In late stages of HIV infection, when the CD4+ T- cell numbers are massively depleted, macrophages remain a major site of continued viral replication.

Although the number of HIV-infected monocytes in the circulation is low, their functional deficits (e.g., impaired microbicidal activity, decreased chemotaxis, abnormal cytokine production, diminished antigen presentation capacity) have important bearing on host defenses.

B Cells in HIV Infection

These patients have hypergammaglobulinemia and circulating immune complexes as a result of polyclonal B cell activation. This may result from multiple factors, including infection with CMV or EBV, both of which are polyclonal B –cell, HIVinfected macrophages produce increased amounts of IL-6, which enhances B cell proliferation.

Pathogenesis of CNS Involvement

Macrophages and cells belonging to the monocyte–macrophage lineage (microglial cells) are the predominant cell types in the brain that are infected with HIV. The virus is most likely carried into the brain by infected monocytes and most experts believe that the neurologic deficit is caused indirectly by viral products and soluble factors (e.g., cytokines such as TNF) produced by macrophages and microglial cells.

3

Diseases of the Immune System lec.3

2014-2015

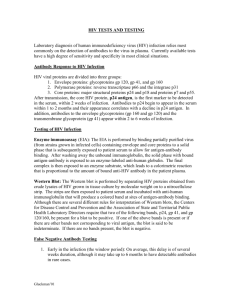

Natural History and Clinical Course

Three phases reflecting the dynamics of virus–host interaction can be recognized:

(1) an early acute phase, (2) a middle chronic phase, and (3) a final crisis phase

The acute phase represents the initial response of an immunocompetent adult to

HIV infection. Clinically, this phase typically manifests as a self-limited illness that develops in 50% to 70% of affected persons 3 to 6 weeks after infection; it is characterized by nonspecific symptoms including sore throat, myalgia, fever, rash, and sometimes aseptic meningitis.

The middle, chronic phase represents a stage of relative containment of the virus.

The immune system is largely intact at this point, but there is continued HIV replication that may last for several years. Patients either are asymptomatic or develop persistent lymphadenopathy, and “minor” opportunistic infections such as thrush (Candida) or herpes zoster.

The final, crisis phase is characterized by a catastrophic breakdown of host defenses, a marked increase in viremia, and clinical disease. Typically, patients present with fever of more than 1 month’s duration, fatigue, weight loss, and diarrhea; the CD4+ cell count is reduced below 500 cells/μL. After a variable interval, serious opportunistic infections, secondary neoplasms, and/or neurologic manifestations (so-called AIDS-defining conditions) emerge, and the patient is said to have full blown AIDS.

4