The history of POW camps at Lamsdorf/Łambinowice

advertisement

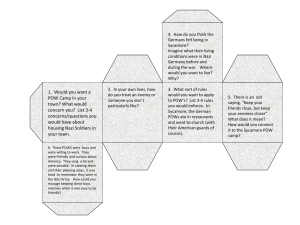

LEARNING ACTIVITY Student worksheet How to stay human when you are being reduced to a number The history of POW camps at Lamsdorf/Łambinowice The history of Lamsdorf (now Łambinowice), a village in the southern-west of Poland) a place where Prisoner-of-War camps were organised goes back to the 19th century. For the first time POW camp at Lamsdorf was established during Franco-Prussian (18701871). At that time the camp housed cc. 3,500 French POWs. The only vestige of the camp is a graveyard with 52 of the French buried in the Old Prisoner-of-War Cemetery. For the second time a POW camp at Lamsdorf was set up during World War I. The total number of the POWs staying there amounted to about 90,000 thousand. There were about 7,000 POWs who did not manage to survive the captivity. The dead were also buried in the Old Prisoner-of-War Cemetery. During WWII, Lamsdorf also played a key role in the history of POW camps. The Nazi military authorities established in Lamsdorf one of the largest POW camp complexes in their territory following a decision made just before the outbreak of war. The first, a POW transition camp (Dulag VIII B), was established in August 1939; by October 1939 it had been re-designated as Stalag VIII B, intended mainly for Privates and noncommissioned officers. After the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, another new camp was created for Soviet POWs (Stalag 318/VIII F), about 2 km away from Stalag VIII B. Two years later, in 1943, further changes took place. In May, Stalag 318/VIII F ceased to function as an independent camp and was absorbed into Stalag VIII B. Following yet more reorganisation, Stalag VIII B was transferred to Teschen (Cieszyn), and the camp at Lamsdorf became Stalag 344. It was divided into two parts: the so-called British camp (Britenlager) and the Soviet camp (Russenlager). The POWs from Lamsdorf provided the basic workforce of the Third Reich economy in Upper and Lower Silesia, especially in the mining industry, in metallurgy, and in agriculture and forestry. They were also employed to construct roads and motorways. By the end of 1943, about 70,000 POWs from the camp at Lamsdorf were employed in over 1,000 Arbeitskommando (working parties), the majority of them Soviet POWs. As a result of extremely harsh working conditions, which included slave labour, malnutrition, extreme exhaustion, disease and brutal treatment, the POWs weakened quickly, had frequent accidents at work and ended up in the camp hospital. Those who managed to recover were forced to rejoin the labour units. Polish soldiers from the September Campaign were the first POWs at Lamsdorf. By October 1939 about 43,000 Polish POWs had been through the camp; after a short stay they were transferred to Stalags and Oflags elsewhere within the Third Reich. In the spring of 1940 most of the Polish Privates and NCOs were ‘officially’ released from the German camps; in reality the Poles were forced to resign their POW status and were transferred as civilian workers. In Lamsdorf the food and living conditions of the Poles were very bad. To begin with they were accommodated in stables and tents with only a few of them accommodated in huts. The others had to build their barracks themselves. After the Poles left Stalag VIII B Lamsdorf in the summer of 1940, various groups of Allied soldiers arrived. In June 1940, the first group of British soldiers arrived, followed, in August, by Belgians, Dutch and French, and Poles from the units organized by General Władysław Sikorski. With time, following further invasions by the German army, other nationalities became How to stay human when you are being reduced to a number | Anna Wickiewicz | Page 1 of 2 LEARNING ACTIVITY interned in the camp, including Yugoslavians, Greeks, Americans, Canadians, Indians, and Slovak and Warsaw insurgents. The principles behind the treatment, protection of soldiers and conditions of their stay at the camp – as was the case in the other POW camps run by the Wehrmacht – were determined by international conventions, including the Geneva Convention of 1929. Although the camp authorities more or less respected the convention as far as Allied soldiers were concerned, they sometimes ignored it. The Allied POWs enjoyed fairly decent living conditions compared to their Polish counterparts. They were accommodated in brick huts which were furnished with stoves and washrooms. However, the barracks were cramped and regulations were frequently revised. They enjoyed the further bonus of being able to supplement their meagre rations (which were the same as those of other nationalities) with Red Cross parcels. Amongst the British POWs was a contingent of men from the Royal Air Force who were not subject to forced labour and therefore were able to organise their leisure time in camp. They were allowed cultural and educational activities, sport, which included football, basketball, volleyball and boxing, and freedom of religious observance. POWs of different armies and nations were treated differently, although Allied soldiers were treated best of all. The Soviet prisoners arrived between July and the autumn of 1941. Initially they were left to live under the open sky and had to look for shelter in holes they dug in the ground. It took some time before they erected their own primitive huts. Their extremely hard living conditions, hunger, exhaustion from long transportation, as well as cruelty inflicted by the guards resulted in high mortality. In October 1941, about 4,000 Soviet POWs were transferred to Auschwitz, while another 2,500 were sent to Gross-Rosen. The German authorities did not feel obliged to look after Soviet POWs as the Soviet Union was not a signatory of the Geneva Convention. Between 1941 and 1945, about 40,000 Soviet POWs died or were murdered at the camp. It is estimated that about 300,000 soldiers of 49 nationalities representing 10 regular armies passed through the camp, including 200,000 Soviets, c. 40,000 Polish soldiers, c. 48,000 British soldiers, c. 17,000 French soldiers, and c. 15,000 Italian soldiers. Other groups included Australians, New Zealanders, Canadians, Hindus and Jews. The British camp at Stalag 344 Lamsdorf evacuated in January 1945, but the Soviet part was liberated by the Red Army on 17 and 18 March 1945, who took the camp’s archives to Soviet Union. How to stay human when you are being reduced to a number | Anna Wickiewicz | Page 2 of 2