Data Triangulation: Institutional Policy Change to Improve Retention

Data Triangulation: Institutional Policy Change to Improve

Retention

Erin Holmes

Director of Institutional

Research and Assessment

Black Hills State

University erin.holmes@bhsu.edu

Abstract – Institutional policy professionals are deluged with a variety of what appears to be unrelated information. Bits of data regarding students, their preparation and their behavior float through our offices. Policy makers are often required to participate in external studies but many professionals do not know how to bring these studies together in an efficient and effective way that is valuable. Too often these data are unconnected which results in a disservice to students and the institution. This case study examines the process by which a variety of data sources including peer retention data, ACT College Progression study, NSSE/BCSSE data and internal and external student data were synthesized and examined. This analysis was conducted to facilitate institutional policy decisions regarding faculty development, first-year curriculum and to enhance student engagement. Issues regarding data triangulation, its concepts and uses in the real world will be discussed.

Simple statistical analyses (ANOVA and OLS regression) will be demonstrated. A discussion of policy changes that occurred as a result, an outline for continued research steps other can take to use existing data will be reviewed.

Student retention has been the subject of research in the academy for nearly fifty years. As Tinto

(2006) so cogently states, models of retention have evolved from simple models based on a student’s individual characteristics that determined his / her success or failure to a multiplicity of nuanced and complicated models that encompass student, institutional, social, faculty, and instructional characteristics

(Tinto, 2006). As knowledge regarding the reasons for student departure has grown so have the solutions to the problem of departure. The centrality of the student retention or departure problem to the mission of the university has resulted in the commitment of many resources to address it. Academic research into the subject has suggested that effective measures to improve retention include improving academic skills of underprepared students, providing orientation to college life designed to ease the transition to college, identify and support at risk students, develop learning communities that increase student engagement, and develop programs that encourage student / college interaction (Adelman, 1999; Braxton & McClendon,

2001; Dodd, 1995). Indeed, the field of retention studies is so rich with solutions and best practices that for an institution attempting to address its own problems with retention it may be difficult to know what to do next, especially if the institution has tried a number of suggested solutions to no avail.

What follows is a case study of an institution that has tried many of the solutions suggested by the literature to improve student retention but has not seen the success it expected. The paper discusses the process by which a variety of data sources, including peer retention information, an ACT College

Progression study, BCSSE and NSSE data as well as internal and external institutional data were

1

synthesized and examined. This synthesis helped policy makers at the institution answer two key questions. First, do students at Black Hills State University (BHSU) come with the appropriate behaviors and expectation to become engaged and successful college students? Second, do BHSU students succeed in their first semester at BHSU at the same levels as do students in South Dakota’s other five public institutions? If the answer to either of these questions is no, what can BHSU do to address them?

Finally, this case study also details how this analysis was used to facilitate institutional policy decisions regarding faculty development and first-year curriculum.

The paper begins with an introduction that places the institution within a contextual framework which describes the institution’s retention issue. Outlined within the introduction is the literature that supports the actions taken to address its retention problems and details of the institution’s current position. The discussion then describes the methods and processes used to identify existing data sources, the statistical methods used during the analysis and how data triangulation was used to pinpoint potential solutions. It presents the results of its data analysis and discusses the policy decisions that were influenced by the analysis. Finally, it offers some conclusions regarding the process, preliminary results, topics for potential research, and plans for assessing the decisions and programs that have been created as a result.

Introduction: The Institutional Context

Black Hills State University (BHSU) is a public, four year institution located in the western part of South Dakota. Founded in 1883 in Spearfish, SD as a normal school, BHSU is now charged by the

South Dakota Legislature to serve the region as a liberal arts college that offers baccalaureate degrees in the Arts and Sciences, teacher education, and business ("Black Hills State University Catalog," 2009-

2010). The institution offers limited degrees at the graduate level including a master of science in curriculum and instruction, a master of science in integrative genomics, and a master of science in strategic leadership. BHSU was recently authorized by the SD Board of Regents to offer a master of business administration in applied management. Total institutional enrollment was 4,076 students in the fall of 2009 with more than half of those students enrolled at its traditional campus in Spearfish and over

1,000 students enrolled at the University Center Rapid City in Rapid City, SD.

As an institution of opportunity for many South Dakota citizens, BHSU has been a less selective institution and has suffered from many of the same problems with retention and graduation rates as its peers. However, the problem has been particularly acute for BHSU. The South Dakota public institutions have averaged between 69 percent for the full-time entering cohort of 2004 to 75 percent retention of its cohort of 2008. Over the same period, BHSU has average from 53 percent to 57 percent

(Integrated Post-secondary Education Data System, 2009).

As would be expected, institutional graduation rates fare no better than the fall to fall retention rates. An analysis of graduation rates of cohorts since 1998 for South Dakota institutions indicate that

BHSU’s 4-, 5-, and 6-year bachelor degree graduation rate averages are roughly half of the system rates

(Integrated Post-secondary Education Data System, 2009).

Finally, a comparison of suspension and probation rates of BHSU students indicate that a larger proportion of its students are suspended from the institution than at its sister institutions in South Dakota.

For 2007-2008, the percentage of students who were suspended was more than twice that of the system percentage, 4.40 percent versus 1.80 percent respectively. Its probation rate for the same period was slightly over 7 percent compared to a system average of 5.90 percent. Though it might be easy to say those rates are indicative of the poor student quality, the difference between BHSU and the other institutions in the system is quite striking.

Dr. Kay Schallenkamp was hired to lead BHSU in 2006. She was well aware of the retention issues at BHSU. She challenged the institution to significantly improve its retention and graduation rates.

At the same time, Schallenkamp emphasized the need to make data driven decisions. In 2008, the university reorganized its office of institutional research and a new director was hired. At the time, the director was charged with discovering the source of the institution’s continuing retention problem.

2

Prior Initiatives

A number of initiatives have been taken to address the student retention conundrum at BHSU.

These initiatives demonstrate the effort BHSU has taken to address its retention and graduation rates over the last decade and they are those often found by other institutions to improve retention rates. The abundant retention literature is clear on those issues that matter to retaining and eventually graduating students: the admission of quality students who are academically and psychology prepared for college learning, the provision of services to students with academic challenges, advising that is early, often and accurate, acculturation of the first year student and last, but certainly not least, early classroom experiences that engage and involve the student in the life of the academy (Astin, 1979; Bean & Eaton,

2001; Dodd, 1995; Tinto, 1982, 1988). BHSU has reviewed and changed policies with the aim of improving student quality and success. Additionally, BHSU has established a range of services for students designed to support integration into the university environment. These policy changes and initiatives changes indicate BHSU’s commitment to student success and improved retention rates. The discussion below outlines the policy changes or added services and ties each to the relevant retention literature.

Student Quality. Admitting better-prepared students is a significant step toward improving retention rates (Tinto, 2002). BHSU cannot simply close its doors to students but it made an important policy decision after President Schallenkamp’s arrival to strictly adhere to SD Board of Regents

(SDBOR) admissions policy. SD BOR policy 2:3, Undergraduate Admissions, allows each institution to conditionally admit certain percentages of students who do not meet the minimum admission standards.

BHSU and all other SD institutions may admit up to 3 percent of its prior entering class of students to baccalaureate programs who did not meet those admissions requirement and up to 10 percent of its prior entering class to associate degree programs. Black Hills State has reduced its conditionally admitted students from slightly over 24 percent of its entering students in the fall of 2005 to only 7 percent of its fall 2009 class. It was anticipated that this policy change would increase the level of student preparation result in increased retention rates.

Services for the Academically Challenged. Even though the number of conditionally admitted students has dramatically decreased, strict adherence to admissions policies has not eliminated all underprepared students. Much of the research into student retention and persistence suggests that the availability of academic support services that are focused on student learning needs and social integration that promote learning are important to increasing student retention and graduation rates (Griswold, 2003;

Tinto, 2004; Trotter & Roberts, 2006). As the research literature regarding the positive impact of such support accrues, BHSU has made serious commitments to incorporate these services into its retention efforts. BHSU has added a number of academic support services including a math center in 2004 and a writing center in 2005. Both of these centers offer professional and peer tutoring for remedial through college level math and English. They encourage students to attend study groups and assist them in accessing other vital student services. In addition to the writing and math centers, BHSU offers remedial education to students who do not qualify for college level math or English courses. Placement into these courses is determined by ACT scores or Compass placement. Only entering students who are less than 21 years old are required to submit ACT scores. Placement into college level work for these students is determined by the English and math subscores. Those students who have an ACT English subscore of 18 or higher are placed directly into College level English. Math placement is determined by both the ACT math sub-score and where the math sub-score is greater than 24, the COMPASS test. Students with math subscores greater than 20 will be placed in college level math (College Algebra or higher) but for the students with subscores higher than 24 the COMPASS score is used to determine placement in college algebra or a higher level math course. Beginning in the fall of 2009, students with ACT reading subscores less than 18 are placed in a remedial reading course. Approximately 316 students take remedial level math each fall and 162 take the remedial English course. Since the remedial reading requirement is

3

a relatively new requirement, the average number of students placed into that course is not known but it is estimated that it will average less than 50 students per semester

Advising. Tinto (1982) states that effective, clear advising is essential to successful retention programs (Tinto, 1982). With that goal in mind, BHSU created the Center for Academic Success in 2002.

The mission of the center is to offer students a central service for advising, tutoring, testing and course placement with a bottom-up approach and direct student intervention. BHSU has had a long running and successful TRIO program that focuses on first generation students, students with disabilities and low income students. This program provides academic advising and support programs for students it engages.

Historically, students participating in the TRIO program have progressed at higher rates than the general population of students.

First year Experience. Since the first year experience is vital to student integration, BHSU has undertaken a number of initiatives to help students adjust to college life. In 2005, it developed Living and

Learning communities in residence halls, and introduced first year experience seminars in 2006. The

Living and Learning communities were not as effective as had been expected and were discontinued. The first year experience seminars continue and are evaluated annually for effectiveness.

Classroom Experience. BHSU began a civic engagement program that acts as a volunteer resource for off-campus entities needing assistance but is not directly linked with classroom activities.

An undergraduate research initiative began in 2006, however, much of these types of activities remain in upper division curriculum with almost none of the lower division curriculum using experiential learning as a method to engage students in the learning process.

Despite the efforts discussed above, BHSU had made only halting efforts to improve classroom instruction. The persistent budget difficulties that effect most public institutions have had serious impacts on BHSU’s ability to provide faculty development funds. Indeed, there were no funds committed to faculty development for a number of years. Those funds that were committed most often focused on the use of technology which did not necessarily translate to better teaching or pedagogy. As Vincent Tinto

(2002) so aptly said in his concluding remarks at the 11 th Annual Conference of the European Access

Network in Prato, Italy, higher education must begin to “take seriously the importance of classrooms to student retention and restructure those settings to promote great student involvement (Tinto, 2002).”

And he added that the higher education community must understand that though faculty may be disciplinary stars, they may not know how to translate that to the classroom. It is the responsibility of the university to “provide faculty with the pedagogical and assessment skills they need to establish conditions in their classrooms” that promote engagement and student success (Tinto, 2002).

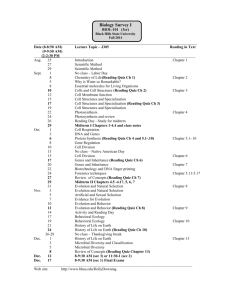

Triggering Event: ACT College Success Study

In October of 2008, BHSU received a report from the South Dakota Board of Regents (SDBOR) that presented strong evidence that pointed to issues in the classroom. The ACT College Success study was commissioned by the SDBOR and it outlined the academic progress of 1999 and 2000 ACT tested South

Dakota High School Graduates entering all six of the Regents’ institutions. The report compared the 1 st year college GPAs and retention rates of students with similar academic preparation based on ACTdetermined College Readiness Benchmarks (American College Testing Board, 2008). These benchmarks correspond to a 50 percent chance of passing the common first year courses. In order for a student to have a 50 percent chance to pass English Composition, they should score 18 or higher on the ACT

English subscore, for college algebra the ACT Math subscore should equal 22 or more. To do well in the heavy reading courses such as history, psychology, or sociology, a student should earn an ACT Reading subscore of 21 and for college biology, the corresponding science reasoning score should be 24 or higher.

A data point in the report is the academic success as measured by first year grade point average of students who met one, two, three, four or none of the benchmarks discussed above. Table 1 below compares BHSU students who met all four of the ACT benchmarks to similar students at the other five

SDBOR institutions. The students who have met all four ACT Benchmarks represent the best students

4

that BHSU enrolls. What is disturbing is the marked difference between the earned GPAs and retention rates at BHSU and the other South Dakota institutions.

Table 1: Comparison of the 1 st year GPAs at the SD six universities of students who met all four benchmarks

Institution 1 st Year Cumulative GPA

Black Hills State University

Dakota State University

Northern State University

South Dakota School of Mines and Technology

South Dakota State University

University of South Dakota

2.77

3.13

3.11

3.01

3.25

3.12

System 3.13

These data raised a great deal of concern among the academic administration. As a result, the administration asked the Director of Institutional Research to answer the following questions:

1. Do students at BHSU arrive here with appropriate behaviors and expectations of engaged learners?

2. Does the GPA situation persist at BHSU? Does it still hold true for cohorts after 1999-2000?

3. What actions should the institution take to help students be more successful in the classroom?

Answering the questions

To answer the questions posed by the academic administrators on campus, the director of institutional research identified existing data sources. This case study is meant to be a practical guide to how an institution might undertake an analysis of existing data to draw its own conclusions regarding its retention issues. What follows is a discussion of how BHSU used BCSSE / NSSE data and system-wide data to answer these questions. The use of a variety of data helps the researcher draw conclusions that are not readily apparent otherwise. Methodological triangulation is described as the use of different methods to explore the same or similar problem. It is thought that the use of multiple methods to arrive at the same conclusion can to bring greater validity and reliability than a single approach to a problem (Gill &

Johnson, 2010; Kapp & Anderson, 2010). Triangulation is also helpful when examining a particularly

“wicked” problem such as student retention. “Wicked” problems are those that do not have easy solutions and need to be approached from a variety of perspectives in order to find a solution (Durant &

Legge, 2006).

Expectations and behaviors for success: the use of BCSSE and NSSE. Academic administrators were very concerned that BHSU students simply did not have the attitudes and behaviors needed to succeed in college and as a result were more likely to perform poorly. To explore this, the director of institutional research turned to the results of a survey that had largely been ignored on campus because it was just another thing the campus was mandated to conduct.

It is widely held that the important factors that lead to student retention include student characteristics, student – institution mutual fit, academic and social interactions with members of the institutional community, and academic achievement (Kuh, Kinzie, Cruce, Shoup, & Gonyea, 2007;

Pascarella & Terenzini, 2005; Tinto, 1982, 1988, 1997, 1998, 2002). As the institutional context indicates, BHSU has incorporated many of the recommendations that are outlined in the literature and which would be natural outcomes of the theoretical models used to understand student retention problems. However, issues of student classroom engagement have not been examined by the institution.

Members of the institution were left wondering if BHSU was attracting students with the capacity to succeed and the will to become engaged. If the students were willing, why were these students not staying at BHSU?

5

The definition of student engagement has changed over time as scholarship has grown surrounding the topic. According to Chapman (2003), engagement in primary and secondary students has includes many types of behaviors including time spent on homework, problems, etc. to a student’s

“willingness to participate in routine school activities (Chapman, 2003).” Routine activities include attending class, asking questions in and out of class, discussing concepts with faculty members and peers

(Skinner & Chapman, 1993). A definition of student engagement in post-secondary setting is similar to that in the primary and secondary setting. Kuh et al (2007) state that for post-secondary institutions, the behaviors described above as engagement are those that can be directly influenced by pedagogy (Kuh, et al., 2007).

A valuable source of information to gauge the post-secondary student engagement levels are two surveys from Indiana University Center for Post Secondary Research at Indiana University at

Bloomington. BHSU has participated in both the Beginning College Survey of Student Engagement

(BCSSE) and the National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) since 2003. The BCSSE has been administered to incoming BHSU freshmen at freshmen orientation / registrations the summer prior to their attendance in the fall each summer. It offers both a retrospective and prospective survey questions.

It asks questions about specific behaviors during a student’s last year in high school and first year in college. As such, it is a suitable gauge for both real and expected behaviors. For example, BCSSE attempts to measure students’ expectations regarding how many hours they plan to study, how often they expect to interact with their faculty members, or how much they expect to work. These questions are thought to be markers of academic engagement (Kuh, et al., 2007; Tinto, 2006; Trotter & Roberts, 2006).

NSSE is a related survey that asks students to review their actual performance or behavior in college. At BHSU, the NSSE is administered every other year to freshmen after their first semester on campus and to seniors who are expected to graduate spring semester. The last survey administration was in the spring of 2008 and the next administration is set for the spring of 2010.

Both surveys are administered electronically. BCSSE return rates are 52 percent for the 2008 administration and nearly 79 percent for the 2009 administration (based on total respondents to total students in cohort). Response rates for NSSE were 31 percent for first year students and 54 percent for senior students during the 2008 administration. Data for first-year students from both BCSSE and NSSE are the focus of analysis here. The data for each survey are aggregated across the survey administrations and are cross-sectional. While the structure of the survey could allow for a panel approach to data analysis, this is not done here because once the matches are made between BCSSE and NSSE responses the number of valid cases would be too low.

The decisions to use particular questions from the surveys are informed by two ideas. First, as in the stock market and in people, past behaviors are always the best predictors for future behaviors. By comparing the reported data from the respondents’ high school years to the subsequent data, it is easy to develop a picture of student engagement and expectations.

Second, active and collaborative courses and engagement with faculty are important to retention of students (Tinto, 2002). Responses and data from the survey are selected to capture key aspects of student engagement including classroom participation, study habits, engagement with faculty and presentations made in class.

The questions examined included the following from both the BCSSE and NSSE surveys:

How often did a student ask questions, expect to ask questions in class?

How often did a student report making a class presentation or expect to make class presentations?

How many hours did the student spend preparing for class or expect to spend preparing for class?

How often did a student report working with other students outside of class?

How often did a student report discussing ideas with faculty members outside of class?

It is hypothesized that the students come into BHSU with the appropriate behaviors and expectations to succeed as measured by responses to questions on both BCSSE and NSSE.

A clear picture of BHSU students develops as the results from BCSSE and NSSE first year students are combined. It is a picture of students who exhibit the appropriate behavior during high school

6

for being successful in college and who expect to continue those behaviors during their first year at college. However, the reports on actual behavior indicate that the students did not behave as they expected.

When students were asked on the BCSSE survey whether they had asked questions in high school, 67 percent responded that they had either often or very often asked questions. Their expectations nearly matched their past behaviors with 67 percent of the respondents saying they expected to ask questions in class often or very often. However, only 48 percent of the student respondents reported actually asking a question or participating in class. This 20 percentage point gap from behaviors exhibited in high school to behaviors exhibited in college can be indicative of reluctance to participate on the students’ part or may be due to a classroom environment at the early stages that does not encourage active and participatory learning.

Nearly half, 46 percent, of the BCSSE respondents reported that they had made class presentation during their last year in high school and 54 percent of the same respondents reported that they expected to make presentations in their college classes. Their actual behavior fell short of this mark with only 37 percent of the NSSE respondents reporting that they had actually made presentations in class. This nearly

20 percent gap

When asked to estimate the time each student respondent had spent preparing for class and how much time they expected to need to prepare, the students generally recognized that they would need to spend more time preparing for college coursework than they had for their high school work. 80 percent of the respondents reported spending between one and ten hours per week preparing for class while only

25 percent said they expected to spend that much time preparing for college classes. 50 percent of the respondents said they thought they would spend between eleven to twenty hours preparing for class and

23 percent expected to spend more than 20 hours per week preparing for class. This equals nearly threequarters of the incoming students stating they had the intention to study eleven hours or more per week.

However, it was found that only 55 percent of the freshmen reported studying their first semester in the

NSSE data. This gap indicates that though the intentions were there, for some reason, the students never followed through with behavior to help them succeed.

Connecting academically with peers outside of class is a key to successful student learning and socialization (Tinto, 1997). However, only 31 percent of BHSU students reported working with students outside of class in high school indicating that this was not an ingrained academic behavior. Though 50 percent stated they expected to work with students outside of class during their first year at college only

32 percent reported actually working with students outside.

The majority of students reported that they never or only sometimes discussed ideas with faculty outside of class. Student / faculty interaction outside of class is thought to be a key component to student engagement (Kuh, et al., 2007). This behavior does not appear to be routine for these respondents. 79 percent stated that they never or only sometimes discussed ideas from class in their last year in high school. Unfortunately 85 percent of the respondents reported the same thing for their first year in college.

While research does not indicate how many questions a student must ask during a class to be successful, how many hours studying is enough or how many class presentations constitute “active learning,” or interact with peers or faculty outside of class, the gaps between expectation and outcome should be cause for concern. From the analysis, it does appear that students are entering with the established behaviors and expectations to succeed in college level work but their actual behaviors fall short of what is needed to succeed. Certainly if one were to plan the purchase of a car or a home and found that one’s expectation for that purchase exceeded actual outcomes the entire purchase would be questioned. In making decisions regarding institutional fit in higher education, students have much more flexibility to walk away from an institution than they would to walk away from the purchase of a car. In the case of Black Hills State, it appears the students are walking away in droves.

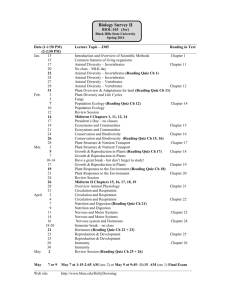

Academic success at BHSU. To answer whether the students at BHSU were any more successful in the near term, an analysis of system-wide ACT Composite scores was conducted. In order to gauge the performance of BHSU first year students to all students within the system BHSU obtained a file from the SDBOR office that contained data on all entering freshmen between 2000 and 2008. This

7

file had 25,525 student records of South Dakota High School graduates with the related ACT Comp score, the students’ first term GPA hours and GPA points. The first fall GPA was calculated by dividing total GPA points by total GPA hours. The resulting GPA is on a traditional 4.00 scale. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine whether the performance of BHSU students as measured by first term GPA was significantly different from the performance of students at the other 5 institutions.

ANOVA was the statistical method of choice for the data because the independent variable, the university in which the student is enrolled, is categorical and the dependent variable, the student’s first term GPA is interval (Iversen & Norpoth, 1987). The ACT Composite score is used as a control variable that groups students based on their score. While the ACT Composite can be defined as interval level data, it is used here as a categorical independent variable which is appropriate since higher order data may be used at any lower order level in statistical analysis (Babbie, 2009).

It is hypothesized that BHSU students with the same ACT Composite scores perform no differently as measured by first term GPA than do those at other institutions. If it is found to be otherwise, questions regarding faculty teaching and assessment should be examined. Table 2 outlines the descriptive statistics for each institution in the South Dakota State system.

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics for South Dakota Entering HS Students

Institution N Mean ACT Comp Mean Fall GPA

Black Hills State University

Dakota State University

Northern State University

3,166

1,958

2,294

1,882

21.38

21.52

21.27

25.21

2.21

2.72

2.63

2.82 SD School of Mines &

Technology

South Dakota State University

University of South Dakota

10,426

5,793

22.93

22.97

2.75

2.66

Though BHSU does not have the lowest mean ACT Composite, it does have the lowest mean Fall

GPA in the system. A simple examination of mean ACT scores and GPAs does not answer the question about BHSU student performance as it relates to their peers across the system. To compare student performance, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to see if BHSU students with the same level of academic preparation as measured by ACT Composite scores performed as well as students at all the other institutions in the system. 61 percent of the students’ ACT composite score fall between 21 and

29 so these students will be the focus here. While both lower and higher composite scores were analyzed, there is little change in the final outcomes.

In all cases, BHSU students had lower mean GPAs than peers within the South Dakota System when controlling for ACT composite score. These differences were statistically significant in all instances except for students with ACT Composite scores of 28.

The results of the ANOVA show that BHSU students’ first term GPAs are lower than their peers at the other public institutions in South Dakota. These differences are significant at almost all levels of

ACT Composite scores, excluding 28. While the percentage of variance accounted for by institution is relatively small highest partial Eta squared equal to 0.019 or nearly two percent of the variance accounted for, the difference in student achievement should be of concern and certainly indicates a continuing problem for Black Hills State University.

8

Table 3: Results of Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) of BHSU Student Performance (First Fall

GPA) with their peers in South Dakota System

First Term GPA

ACT

Composite

Score BHSU

All

Others F Significance

Partial Etasquared

21

22

23

24

2.30555

2.4273

2.3512

2.568

2.5642

2.6376

2.7391

2.9354

21.846

15.732

38.537

41.519

***

***

***

***

0.009

0.007

0.019

0.016

25

26

27

28

2.6533

2.783

2.8929

3.1717

2.9745

3.0412

3.1893

3.2774

22.31

9.58

12.641

0.978

***

**

***

0.011

0.006

0.01

0.001

29 2.9761 3.3286 6.447 ** 0.01

***p<0.001; **p<0.05; *p<0.10

To verify the results of the ANOVA, the student data were run through a regression procedure in

SPSS. The first model included on the ACT Composite score and the student’s fall semester GPA. The impact of the ACT Composite on the dependent variable of fall semester GPA was positive, for every one point increase in ACT Composite this model predicted a 0.046 point increase in fall GPA (p<0.001; adj. r-squared = 0.073).

The addition to the model of an institution dummy variable (1 = BHSU; 0 = All Others) was found to significantly improve the model, both variables were significant (p<0.001; adj. r-squared =

0.093). The coefficient for BHSU versus all others indicated that a student with a particular ACT composite score at BHSU could expect to have a GPA that is 0.442 points lower than another student with the same ACT composite score at any other South Dakota institution.

A number of arguments can be raised to dispute the validity of the information here. First, this simple examination of a narrow range of variables, ACT Composite and first fall grade point average, does not account for all of the factors that inform scholars regarding retention problems. This is true, it does not account for student characteristics such as race, age, first-generation status, etc. What the sample does examine are a relatively homogenous group of students, South Dakota High School graduates enrolling in South Dakota Public institutions are not known for their diversity. These students come from largely rural backgrounds, are slightly more than 90 percent white and are of the same age group. The homogeneity of the group would lead one to suppose that there would be little or no significant differences between the groups especially once ACT Comp is controlled.

It has been argued on campus that the lower grade point average at BHSU is indicative of poor student quality and nothing else. However, the data here do not support that argument as the comparisons are made within ACT composite scores. If ACT composites are an accurate gauge of a student’s ability, one would expect student performance as measured by fall GPA to be similar and it is not.

It could also be argued that the differences are simply artifacts of curriculum, that the levels of rigor and types of courses taken at different institutions would preclude any performance analysis or comparison. It should be noted that as a state system, South Dakota has taken great pains to systemize the general education curriculum. While the courses are not identical by any means, students are expected to meet the same standards and take the same courses across the state which should neutralize the majority of the questions regarding the curriculum.

Finally, many on campus argue that the students’ grades reflect attendance problems at the university. Attendance has been found to be a key indicator of student success (Tinto, 2002). If the

9

assumption of homogeneity of student characteristics and general education curriculum discussed above is true, the students at BHSU should be no more likely to be absent from their classes as other students at the other five universities. If the students are absent more often than why are these absences occurring?

While there is still more research to be conducted, the conclusion is that there is a disconnect between the classroom and student engagement.

Conclusions and Future Research

These results indicate that students coming to BHSU had the appropriate academic habits from high school and intent to succeed at BHSU but, based on the GPA comparisons, are not succeeding at

BHSU as similar students at other institutions. These data, coupled with the academic progression data from ACT, the institutional data as well as the contextual information regarding student support services, indicated that the students were not being adequately engaged in the classroom.

A number of additional initiatives have taken place during the past academic year. Beginning with fall 2009, faculty development funds have been committed to improving instructional pedagogy. A half-time pedagogy specialist is working with general education faculty members. The faculty members were invited to participate in instructional improvement workshops offered before the beginning of the fall semester. They were also offered the opportunity to receive intensive assistance incorporating active and collaborative learning techniques into their classrooms. Sixty faculty members participated in the summer workshops and many elected to receive intensive assistance. Even in the face of budget cuts, the president elected to keep the pedagogy specialist under contract to continue her work for the upcoming academic year.

A second initiative includes an examination of introductory curriculum. The first year seminar and remedial math, have both been reviewed. A number of changes were made to the curriculum in those courses both as a result of the information contained in this case study as well as other contextual information. Finally, President Schallenkamp constituted an Enrollment Management Task Force this last academic year to address issues of retention and consider options for improving student engagement.

While these initiatives are steps in the right direction, more is left to be done. Some future research steps include an analysis of BHSU’s student evaluation instrument as a source for faculty development. More research regarding the instructional needs of students must be conducted so that

BHSU can best marshal its resources to meet the needs of its students. Continued assessment of services rendered to students must be conducted here at BHSU. There is little evidence of organized assessment of any of the services that were initiated to address its retention issues. Finally, it would be worthwhile to link the information here, both the survey data and the ACT Composite information, with retention information to search for potential patterns.

In the final analysis, however, this project was more important as a guide for the researcher to take steps in using existing data to answer questions about students. Five distinct steps took place during the process that might help others explore existing data to help answer wicked questions.

1.

Learn about your institution, the steps it has taken to address problems.

2.

Watch for unexpected moments where data point to something you had not thought of before. This moment occurred here when BHSU received the ACT benchmark study.

3.

Know what you have in your toolbox. Take time to explore and understand your existing data.

4.

Do not be afraid to draw conclusions from different types of data. You may be wrong but you will at least have taken the time to consider the information you have.

5.

Read the literature! It helps you to develop a fundamental understanding of questions that are asked.

10

References

Adelman, C. (1999). Answers in the Tool Box: Academic Intensity, Attendance Patterns, and

Bachelor's Degree Attainment . Washington, DC: US Department of Education.

American College Testing Board. (2008). College Success - Individual College Report : South

Dakota Board of Regents.

Astin, A. (1979). Student involvement: a developmental theory for higher education. Journal of

College Student Personnel, 25 , 297-308.

Babbie, E. (2009). The Practice of Social Research . Belmont: Thomson-Waadsworth.

Bean, J. P., & Eaton, S. B. (2001). The psychology underlying successful retention practices.

Journal of College Student Retention, 3 (1), 73-89.

Black Hills State University Catalog. (2009-2010). In B. H. S. University (Ed.). Spearfish, SD.

Braxton, J. M., & McClendon, S. A. (2001). The fostering of social integration and retention through institutional practice. Journal of College Student Retention, 6 (4), 425-445.

Chapman, E. (2003). Assessing Student Engagement Rates. ERIC.

Dodd, J. M. (1995). American indian student retention and withdrawal. College and University,

31 , 435-437.

Durant, R. F., & Legge, J. S. (2006). 'Wicked Problems,' Public Policy, and Administrative

Theory: Lessons from the GM Food Regulatory Arena. Administration & Society, 38 (3),

309-334.

Gill, J., & Johnson, P. (2010). Research Methods for Managers (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage Publications.

Griswold, G. (2003). Writing centers the student retention connection. Academic Exchange

Quarterly (Winter).

Integrated Post-secondary Education Data System. (2009). Peer Analysis System. Retrieved

10/20/2009, from U . S. Department of Education:

Iversen, G. R., & Norpoth, H. (1987). Analysis of Variance (Vol. 1). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

University Papers.

Kapp, S. A., & Anderson, G. R. (2010). Agency-Based Program Evaluation: Lessons from

Practice . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing.

Kuh, G., Kinzie, J., Cruce, T., Shoup, R., & Gonyea, R. M. (2007). Connecting the Dots: Multi-

Faceted Analyses of the Relationships between Student Engagement Results from the

11

NSSE, and the Institutional Practices and Conditions that Foster Student Success .

Bloomington, IN: Center for Postsecondary Research, Indiana University Bloomington.

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How College Affects Students: A Third Decade of

Research (Vol. 2). San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

Skinner, E., & Chapman, M. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 85 (4), 571-581.

Tinto, V. (1982). Limits of Theory and Practice in Student Attrition. The Journal of Higher

Education, 53 (6), 687-700.

Tinto, V. (1988). Stages of Student Departure: Reflections on the Longitudinal Character of

Student Leaving. The Journal of Higher Education, 59 (4), 438-455.

Tinto, V. (1997). Colleges as communities: Exploring the educational character of student persistence. Journal of Higher Education, 68 , 599-623.

Tinto, V. (1998). Colleges as communities: Taking the research on student persistence seriously.

Review of Higher Education, 21 , 167-178.

Tinto, V. (2002). Promoting Student Retention: Lessons Learned from the United States.

Paper presented at the 11th Annual Conference of the European Access Network, Prato, Italy.

Tinto, V. (2004). Student Retention and Graduation: facing the truth, living with the consequences . Washington, DC: Pell Institute.

Tinto, V. (2006). Research and practice of student retention: what next? Journal of College

Student Retention, 8 (1), 1-19.

Trotter, E., & Roberts, C. A. (2006). Enhancing the early student experience. Higher Education

Research & Development, 25 (4), 371-386.

12