Action Research: Disruptive Behavior and Transition Time

advertisement

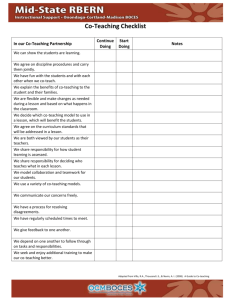

Running Head: COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING Collaboration and Co-Teaching By XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Concordia University: FPR 6656 Seminar in Reflective Practice Mr. Greg Wolcott Month Date, Year 1 COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 2 Abstract This research investigates how identifying one of six specific co-teaching models, when co-planning for instruction, impacts communication and collaboration between coteaching colleagues. Co-teaching utilizes two teachers, a general education teacher and a special education teacher, and their specific skills and expertise to meet the needs of all learners in the general education setting (Murawski, 2012). In this study two general education teachers participated in co-planning and co-teaching with a special education teacher. During co-planning general education teachers completed a survey, identified specific co-teaching models that would be employed during co-teaching, and competed a co-teaching checklist. Data indicated that when co-teaching colleagues identify specific co-teaching models and used a co-planning checklist during planning instruction, collaboration and communication increased. COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 3 Introduction My current role at my school is the 4th and 5th grade resource teacher. I am responsible for twelve students’ Individual Education Plans (IEP) and ensuring that each individual with an IEP in the 4th and 5th grades receives the appropriate differentiation, accommodations, and modifications outlined in his or her specific IEP to best meet his or her individual needs. I often find myself fretting over and feeling lost about ensuring that my students have their instruction appropriately differentiated and modified to meet their individual needs. I struggle with maintaining the constant communication and collaboration with the classroom teachers in order to know exactly what is happening in the classroom so that I can adjust and modify the material to make sure that the individual students will feel success in the classroom. I was interested in researching and investigating more effective and efficient techniques for collaborating with teachers and differentiating the different subjects in which my students participate. The goal is for my students to have successful elementary school careers with access to the general education curriculum with modifications and accommodations specific to their needs. To accomplish this goal I want to provide support for the classroom teachers in the planning stages of their instruction so that the curriculum is presented in a differentiated manner to meet the needs of all students. Establishing strategies and practices that increase collaboration and differentiation will be a vital tool for all teachers and special educators. The teachers will feel supported when teaching students with IEPs and 504 plans, and the students will feel success because the material and assignments are presented in a way that meets their needs. COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 4 Literature Review Students with learning disabilities are required to have access to curriculum (Embury & Kroeger, 2012) in their least restrictive environment (LRE) as frequently as possible. For most students with learning disabilities, the LRE is the general education classroom. One approach to effectively and efficiently achieve inclusion of students with learning disabilities into the general education setting is through collaboration (Carter, Prater, Jackson, & Marchant, 2009). Collaboration, or co-teaching, implements and highlights the strategies and expertise that both a special-educator and general education classroom teacher possess (Murawski, 2012). Cook & Friend (1995) define co-teaching as two professional educators delivering instruction and lessons to students’ at all academic levels within a single space. Co-teaching is a partnership that includes two professionals working together on planning, presenting instruction, and assessing and evaluating a group of diverse learners (Cook & Friend, 1995). Duchardt, Marlow, Inman, Christensen and Reeves (1999) state that “co-teaching may provide powerful ways to address the needs of a diverse population of students in both higher education and general education” (p. 186). For successful collaboration and co-teaching to benefit students with a variety of learning needs, Cook & Friend (1991) identify six characteristics that co-teachers need to employ including a voluntary relationship, parity between the teachers, mutual goals, shared responsibilities and decision making, sharing ideas and resources, and responsibility and accountability of outcomes. When these six characteristics are practiced in a co-teaching program, what results are high levels of collaboration that are more effective than a program with little collaboration (Santamaria & Thousand, 2004). COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 5 When co-teachers collaborate and employ the six characteristics stated above, students with a variety of educational needs benefit (Santamaria & Thousand, 2004) in various ways. In a study by Welch (2000) it was observed that students with disabilities, in a co-taught classroom, made gains in reading and spelling. Mahoney (1997) found that students with disabilities in a co-taught classroom engaged with new peers and made more friends. Additionally, Santamaria and Thousand (2004) identified that students observe and emulate the collaboration and cooperation displayed and modeled by their co-teachers. Co-Teaching Models Friend and Cook (1995) identified six possible co-teaching models to meet the needs of learners. They state that one model should not be used exclusively and that all models should be used over the course of instruction. The six models include: (i) One teach / one assist, (ii) one teach / one observe, (iii) station teaching, (iv) alternative teaching, (v) parallel teaching, and (vi) team teaching. Each model has positive features to meet students’ needs. Additionally, each model has drawbacks that require attention from both co-teachers. With the “one teach / one assist” model, both co-teachers are actively engaged in the instruction. However, one co-teacher is the lead teacher and the other teacher assists students as needed (Friend & Cook, 1995). This co-teaching model is the most often used model in co-teaching because it requires little preparation and collaboration between teachers. However, there is little parity in this model as one teacher is the lead teacher and the other teacher does not have much influence in the instruction and decisionmaking (Friend & Cook, 2003). COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 6 “One teach / one observe” is similar to the “one teach / one assist” model. The “one teach / one observe” model differs in that the teacher that observes takes detailed notes and collects data on the students and the teacher. This model requires co-planning to identify the specific data to be collected and to analyze and reflect on the collected data (Embury & Kroeger, 2012). A third co-teaching model is “station teaching”. This model includes teachers dividing content into separate stations through which students will rotate, with each teacher leading a station of particular content. This approach requires co-planning and collaboration to identify the stations and shared responsibility of the content covered (Embury & Kroeger, 2012). “Alternative teaching” involves one teacher pulling a small group of students from the large group to reinforce or pre-teach curricular concepts. This approach often meets the diverse needs of students with learning disabilities. This approach also requires co-planning to ensure the needed skills and concepts are covered in the small group (Embury & Kroeger, 2012). “Parallel teaching” is a fifth approach that involves each teacher instructing the content to half of the students in the class. Both teachers are presenting the same information. However, the student-teacher ratio is smaller which could benefit a variety of instructional activities including hands-on and partner work. This model requires prior co-planning to ensure that both teachers are presenting the same material to the different groups of students (Embury & Kroeger, 2012). A final model is “team teaching”. In team teaching both teachers are equal in the co-planning and the presentation of the material. Teachers may take turns presenting the COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 7 content or present it together with each person building off what the previous teacher just stated. This co-teaching approach requires co-planning and a level of comfort to present the material together (Cook & Friend, 1995). Co-Planning Murawski (2012) notes, “co-planning is both the most important and the most difficult component of co-teaching” (p. 8). Without co-planning teachers do not prepare for differentiation of material and often will automatically fall to the “one teach / one assist” co-teaching model (Murawski, 2012). For effective co-planning that result in effective co-teaching, teachers need to dedicate time for the planning stage (Murawski, 2012). Co-teachers “need to be equally invested and have equal status in the classroom” (Howard & Potts, 2009, p. 3); this includes taking ownership of the partnership and dedicating time to meet, plan, and prepare for co-teaching. Areas of focus during coplanning include identifying learning standards, assessments, and accommodations / modifications (Howard & Potts, 2009). Additionally, co-teachers need to determine clear co-teaching roles, which include identifying the co-teaching model they will employ during instruction (Murawski, 2012). When collaboration is structured, properly planned, and is supported by administration, “educational outcomes improve for students with disabilities” (Carter, Prater, Jackson & Marchant, 2009, p. 60). When teachers fail to plan the support and accommodations needed for students with learning disabilities, instruction may not be individualized and fail to meet the needs for the students with disabilities (Carter, Prater, Jackson & Marchant, 2009). COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 8 Research Questions I aimed to increase communication and collaboration with my colleagues in an effort to effectively and efficiently differentiate both instruction and assignments to meet the needs of students with IEPs. I struggled with supporting and modifying all of the various classes for students with IEPs. Modifications and accommodations were not provided because co-planning and collaboration was too rushed or the co-planning was not focused. Through the action research process I evaluated how identifying one of the six co-teaching models (Cook & Friend, 1995) during the co-planning stages impacted co-teacher collaboration and communication. My objective for this specific focus was to address the following question: 1. How will identifying the specific co-teaching model when planning with colleagues impact collaboration? It was my goal that identifying the specific co-teaching model would increase collaboration, differentiation and modifications while increasing the practice of coteaching. With an increase in those areas I expected an improvement in success for students with IEPs. Methodology Participants Two teachers, Mrs. Phillip (pseudonym), a fourth grade teacher, and Mrs. Williams (pseudonym), a fifth grade teacher, participated in the collaboration process of co-planning and co-teaching. These two teachers were selected based on their students’ needs in their classrooms and willingness to collaborate and co-teach. COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 9 The fourth grade teacher, Mrs. Phillip, has taught for four years. Her experience includes teaching first grade, fifth grade, and fourth grade. She has a Masters in Literacy and is working towards a Masters in Special Education. Mrs. Phillip’s fourth grade class consists of 23 students, four of which have individual education plans (IEPs) to address learning disabilities, and two students are identified as English Learners (EL students). The fifth grade teacher, Mrs. Williams, has taught for 15 years. Her experience includes teaching gifted and talented students (GATE) and fifth grade. Mrs. Williams has a Masters in Education. Her fifth grade class consists of 19 students, four of which are identified as having learning disabilities, and two are EL students. The kindergarten through fifth grade school in which the study took place is a single elementary school in the school district. The school averages approximately 300 students, with a pupil-teacher ratio of 10 to 1. The school’s racial/ethnic background is 55 percent white, 30 percent Asian, 7 percent black or Hispanic, and 9 percent two or more races. Eighteen percent of students qualified for IEPs; 2 percent of students are identified as Limited English Proficient, and 4 percent of students are identified as lowincome and qualify for free and reduced lunch. Intervention/Innovation This study examined how identifying the specific co-teaching model when planning with colleagues impacts collaboration. I used mixed method data collection that included quantitative and qualitative data. Validity was ensured by using three data sources and triangulation to support my findings. COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 10 This study involved co-planning and co-teaching with two colleagues: one colleague teaching fourth grade and the second colleague teaching fifth grade. I coplanned with each individual teacher one day a week for four weeks and we co-taught together over a three-week period. I met with the fourth grade teacher on Friday mornings, and I met with the fifth grade teacher on Monday afternoons. These times were selected based on schedules and availability. During the first co-planning session the co-teachers completed a co-teaching survey. Additionally, during the co-planning time we planned for the following five days of instruction, and we identified which coteaching model would be followed during instruction for each of the following five days. We also completed the co-planning checklist during the weekly co-planning time; we marked off areas of planning that we addressed while leaving areas of planning that we did not address blank. During co-teaching instruction in the general education classroom I identified the co-teaching model that was implemented and took note as to whether it was the model that was selected during co-planning. This routine of co-planning and coteaching continued for two additional weeks, for a total of three weeks of co-teaching. On the fourth day of co-planning the co-teachers completed the same co-teaching survey provided to them at the beginning of the study to conclude the study. Data Collection I used three sources of data collection to gather information regarding the impact that identifying the specific co-teaching model when co-planning with colleagues had on collaboration. The three sources of data helped determine whether naming the specific co-teaching model when co-planning increased the collaboration and planning with my COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 11 colleagues. Using the three data sources and triangulation of the information to support my findings ensured validity. First, I documented the specific co-teaching model identified in the weekly coplanning stages of collaboration, and then documented whether that model was practiced during instruction. During our daily co-teaching instruction I took note of what coteaching model was implemented, and I noted whether it was the model that was identified during our co-planning time. Second, I completed a co-planning checklist during our weekly co-planning time. This checklist observed and recorded our weekly co-planning collaboration. This item of data documented what areas of planning we focused on during our co-planning. The checklist includes standards, assessment, homework, accommodations, modifications and co-teaching model. Third, I provided a co-teaching survey. Teachers collaborating in this study participated in a co-teaching survey at the onset and conclusion of this study. This survey recorded the ideas and opinions of my colleagues regarding co-teaching and co-planning. Ethical Considerations I have participated in the Institutional Review Board (IRB) training and have included IRB documentation within this proposal. There is no risk for participants participating in this study. The data collection is for my professional development and did not subject participants to risk in any way. Providing pseudonyms for all participants in this study ensures confidentiality. Data and information collected contains pseudonyms or does not contain names to ensure confidentiality. All data and extraneous information have been shredded since the study has been completed. Anticipated COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 12 benefits of this study included collaboration and communication with colleagues while co-teaching. This increase in collaboration and communication was anticipated to improve instruction for all students in the classroom. Results A mixed method of data collection that includes quantitative and qualitative data was used in this study. Three sources of data enabled triangulation of information, ensuring validity of the data. The three sources of data are provided for both the fourth and fifth grade co-teachers. The data includes a pre and post survey of the co-teachers participating in the study, documentation of planned co-teaching models and co-teaching models that were implemented during instruction for both classrooms, and a co-planning checklist documenting the co-planning sessions. At the first co-planning session, held individually for the fourth grade teacher and the fifth grade teacher, each teacher completed the co-teaching survey. In the pre-survey, both teachers indicated that they both strongly agree that they regularly co-plan with their colleagues, that co-planning is time well spent to meet the needs of all learners, and coteaching is valuable for meeting the needs of all learners. The fourth grade teacher strongly agreed that she is comfortable with co-teaching whereas the fifth grade teacher agreed that she is comfortable with co-teaching. They both disagreed or strongly disagreed that they were familiar with and implemented the five co-teaching models. They both commented that they did not know if they implemented the various coteaching models because they did not know the different models. When asked to provide comments about the benefits of co-planning and co-teaching they stated that co-planning is beneficial for sharing ideas, providing different perspectives, and meeting the needs of COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 13 learners. Additionally, the fourth grade teacher commented that co-planning is helpful for sharing roles and saving time and energy. Concerns with respect to co-planning and co-teaching included (i) difficulty scheduling time to regularly meet and collaborate, and (ii) the possibility that personalities may not complement one another. The fifth grade teacher also stated that co-teaching is difficult if teachers employ different teaching styles. At the conclusion of the three-week data collection the teachers completed the same survey to document their thoughts regarding the action research. The teachers responded similarly that co-planning and co-teaching are valuable for their teaching and the students’ instruction. They strongly agree that they were familiar with the five coteaching strategies by the end of the three-week action research and agreed or strongly agreed that they utilized the different co-teaching models in their instruction. The teachers provided additional comments that were similar to the pre-survey stating that the benefits of co-planning and co-teaching include improved organization, differentiation, and collaboration. As with the pre-survey the teachers commented in the post-survey that they still had concerns with finding time to co-plan and effectively collaborate. Additionally, finding the right co-teacher with a personality complementary to their teaching style remained a concern with co-teaching. This data reflects that teachers are aware that co-teaching is an important tool for meeting the needs of all learners. It also demonstrates the teachers’ lack of awareness regarding the various co-teaching models prior to initiating this action research. Therefore, the teachers did not know if they implemented the different co-teaching models during their co-teaching instruction. By the end of the three-week case study the COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 14 teachers were aware of the co-teaching models and agreed that they utilize the different models of co-teaching. The second source of data collection included identifying a specific co-teaching model to implement during co-teaching instruction and then documenting whether the identified co-teaching model was practiced during the co-teaching instruction (Appendix D). In fourth grade, three out of the five different co-teaching models were planned for instruction over the three-week data collection period. These three models were the only models implemented during the action research. During the first week of coteaching in fourth grade, 40% of the planned co-teaching models were implemented. During this time three days were planned for station teaching. However, during instruction the model was adjusted to the regrouping model to better meet the needs of the students. Following the third day we collaborated and changed the planned coteaching model to regrouping and followed this model for the remainder of the week. The second week in fourth grade we followed the planned co-teaching model 80% of the time, and the third week we followed the planned co-teaching model 100% of the time. In fifth grade one out of the five different co-teaching models was planned for instruction over the three-week period. During instruction two models, including the originally planned model, were implemented during instruction. Over the first week, we followed the planned co-teaching model 100% of the time. However, in the second week, we implemented the planned co-teaching model 40% of the time and we implemented the planned co-teaching model 60% of the time during the third week. During instruction it was observed that students required a different approach to scaffold COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 15 instruction to meet their needs. As a result, the planned co-teaching models were not implemented. In fourth grade the implementation of the planned co-teaching model consistently increased over the three-week period. In fifth grade the implementation of the planned co-teaching model decreased over the three-week period. For both grade levels a change in co-teaching model was made in response to student needs. Instruction changed based on how well the students responded and understood the instruction and content taught. If we observed that students required more direct, small group instruction, we responded to the student feedback and adjusted our co-teaching model accordingly. It was also observed that during the planning stages teachers choose co-teaching models with which they were familiar. During instruction, however, the model could change based on student needs, and not all of the five co-teaching models were attempted during the three-week period. The third source of data involved the co-planning checklist. The co-planning checklist recorded the areas that were covered during the co-planning sessions with each of the co-teachers. This co-planning checklist was completed three times for each grade (Appendix E). In fourth grade 80% of the co-planning checklist was identified as being covered during the first and second co-planning sessions. During the first two sessions we covered standards, assessment, homework, accommodation/modification and coteaching. During the first week of planning, one item related to homework on the checklist and one item related to accommodations/modifications on the checklist were not discussed. During the second week accommodations/modifications on the checklist COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 16 were not discussed. During the third week 70% of the items on the co-planning checklist were discussed. The section related to homework and a portion of the section related to accommodations/modifications was not discussed during the third week. In fifth grade the areas discussed and addressed during co-planning increased over the three-week data-collection period. Thirty percent of the co-planning checklist was discussed the first week. We identified learning goals, the co-teaching model for instruction, and instruction of the class utilizing the co-teaching model. The following week, 50% of the co-planning checklist was covered. That week we reviewed the standards, assessments, homework, and the co-teaching model and instruction utilizing the co-teaching models. During the final week 80% of the co-planning checklist was discussed. The areas not covered during the final week of co-planning included identifying student learning goals, and addressing student IEP goals. In fourth grade we consistently addressed a large number of the areas on the coplanning checklist over the three week period and in fifth grade the areas covered in our co-planning sessions increased over the three week period. Overall in fourth grade the co-teacher recognized the importance of co-planning and co-teaching. Planned co-teaching models that were implemented increased over the three-week period and on average 80% of the areas of instruction were covered during co-planning stages. This data displays that our communication regarding the identification and implementation of co-planning models increased over the three-week period and that we employed strong communication regarding our co-teaching instruction from the outset of the case study. COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 17 The fifth grade co-teacher also demonstrated that she values co-planning and coteaching to meet the needs of learners. The planned co-teaching models that were implemented during instruction fluctuated, however, over the three-week time period. Based on the data reflected in the co-planning checklist, our planning regarding instruction during co-planning time increased over the three-week period. We initially only covered 30% of the co-planning checklist during our first week of co-planning and by the third week of co-planning we covered 80% of the co-planning checklist. However, our communication with respect to co-teaching models did not increase over time as was reflected by the fluctuating correlation between co-teaching models planned for instruction and co-teaching models implemented during instruction. Overall, identifying a specific co-teaching model during co-planning did increase communication and collaboration between co-teachers. Scheduling co-planning work sessions in advance that identify instruction and student needs further increased the quality of the planning for co-teaching. Discussion This action research project investigated whether identifying a specific coteaching strategy while co-planning increased collaboration and communication between co-teachers. The data suggests that communication and collaboration do increase when a specific model of co-teaching is identified during co-planning. Both teachers that participated in this action research project identified the benefits stemming from co-planning and co-teaching. They valued the teamwork and collaboration that develop while planning and teaching with another teacher with a background that differs from their own backgrounds. They did, however, identify COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 18 limitations of co-teaching and co-planning including finding sufficient, common time to plan and prepare for co-taught lessons. Murawski (2012) also stated that co-planning requires dedicated time to be effective, but it is often the most difficult component of coteaching. My colleagues also identified the need to collaborate with a teammate that has a similar philosophy regarding education and to work with a teammate that has a likeable personality, which is included in Cook and Friend’s (1991) six important characteristics to have positive co-teaching experiences. Finding sufficient time to collaborate and plan did not prove to be as difficult as expected. This year, our school has incorporated three hours of collaborative planning into our monthly teacher expectations. With this expectation, finding collaborative time to meet with my colleagues has been successful. Prior to this year encouraging my colleagues to plan outside of the school day was a challenge. Meeting regularly to plan and discuss lessons and instruction has increased collaboration, co-teaching, and differentiation within instruction. Through this study I observed that teachers lacked the ability to identify the various co-teaching strategies that can be employed while teaching with another teacher. Once the teachers were informed of the different strategies the teachers admitted that they were familiar with a few of the approaches but did not know all of them. Throughout the study teachers consistently identified the same co-teaching models to implement in the classroom that they employed prior to being exposed to the alternative co-teaching models. That is, they did not differ with respect to their approaches after they were exposed to the various alternative co-teaching strategies. Perhaps the teachers were comfortable with the few styles of co-teaching that they always employed. Perhaps the COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 19 teachers did not understand or have the time to prepare for the alternative co-teaching approaches. The teachers did not express feelings towards the co-teaching models that they did not choose; they simply consistently selected strategies that they had previously employed. Due to the co-planning checklist I was aware of the areas of planning we targeted when we met to prepare for weekly lessons. I observed that the fourth grade teacher and I were consistent with what we discussed and covered during our planning sessions. We worked well together for the past two years, and throughout this time we regularly met and planned. Historically, our planning sessions have been student focused, identifying areas of differentiation and accommodations to meet the needs of all learners. Through this action research process the only adjustment we made to our co-planning time involved the identification of a specific co-teaching strategy to employ. We easily covered the co-planning checklist during our planning sessions, which we have practiced over the last two years. The fifth grade teacher and I did not regularly co-plan prior to this action research project. Prior to this project I would quickly ask her what the day’s lesson would cover while walking into her classroom, and I would make a real-time decision as to how to best support my students. This action research required regular co-planning sessions to identify a co-teaching model, however, so we discussed the lessons for the week and shared ideas and collaborated with respect to how I could best support the class during instruction. According to the data, our communication regarding the co-planning checklist clearly improved over the three weeks of the study. COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 20 Following this action research project I will continue to encourage my co-teachers to regularly co-plan and identify specific co-teaching strategies to implement during instruction. Additionally, I will continuously use the co-teaching checklist as a tool to help document and drive our co-planning sessions. This action research project identified that meeting regularly to co-plan and collaborate to identify a specific co-teaching model increased our communication. Further research questions that would be important to pursue include: (i) How does a coplanning checklist / co-planning template improve teacher collaboration and (ii) how does co-planning increase student success in the classroom. COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING Appendices Appendix A: Co-Teaching Survey Appendix B: Co-Teaching Models Appendix C: Co-Planning Checklist Appendix D: Co-Teaching Model Tracking Sheet Appendix E: Co-Planning Checklist Data 21 COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 22 References Carter, N., Prater, M., Jackson, A., & Marchant, M. (2009). Educators' perceptions of collaborative planning processes for students with disabilities. Preventing School Failure, 54(1), 60-70. Cook, L., & Friend, M. (1991). Principles for the practice of collaboration in schools. Preventing School Failure, 35(4), 6-9 Cook, L., & Friend, M. (1995). Co-teaching: Guidelines for creating effective practices. Focus on Exceptional Children, 28(3), 1-16. Duchardt, B., Marlow, L., Inman, D., Christensen, P., & Reeves, M. (1999). Collaboration and co-teaching: General and special education faculty. Clearing House, 72(3), 186-90. Embury, D., & Kroeger, S.D. (2012). Let’s ask the kids: Consumer constructions of co teaching. International Journal of Special Education, 27(2), 102-112. Friend, M., & Cook, L. (2003). Interactions: Collaboration skills for school professionals (4th ed.). New York, NY: Allyn and Bacon Howard, L., & Potts, E. A. (2009). Using co-Planning time: Strategies for a successful co-teaching marriage. TEACHING Exceptional Children Plus, 5(4), Mahoney, M. (1997). Small victories in an inclusive classroom. Educational Leadership, 54(7), 59-62. Murawski, W.W. (2012). 10 Tips for using co-planning time more efficiently. Teaching Exceptional Children, 44(4), 8-15. COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 23 Santamaria, L., & Thousand, J. (2004). Collaboration, co-teaching, and differentiated instruction: A process-oriented approach to whole schooling. International Journal Of Whole Schooling, 1(1), 13-27. Welch, M. (2000). Descriptive analysis of team teaching in two elementary classrooms: A formative experimental approach. Remedial and Special Education, 21(6), 366-376. COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 24 Appendix A Co-Teaching Survey Please complete the survey below honestly by circling a response to each question. Do not include your name. 1. I regularly co-plan for my instruction with my colleagues. Strongly disagree Disagree Agree Strongly agree 2. Co-planning is time well spent to meet the needs of all learners. Strongly disagree Disagree Agree Strongly agree 3. I am comfortable with co-teaching. Strongly disagree Disagree Agree Strongly agree 4. Co-teaching is valuable for meeting the needs of all learners’ in my class. Strongly disagree Disagree Agree Strongly agree 5. I am familiar with the five different co-teaching models. Strongly disagree Disagree Agree Strongly agree 6. When co-teaching we utilize the five different co-teaching models. Strongly disagree Disagree Agree Strongly agree List 2 to 3 benefits of co-planning. List 2 to 3 concerns regarding co-planning. List 2 to 3 benefits of co-teaching. List 2 to 3 concerns regarding co-teaching. Additional comments regarding co-planning and co-teaching. COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING 25 Appendix B Co-Teaching Models Co-Teaching Model Class Setup Definition Whole Class B One co-teacher is the lead teacher and the other co-teacher assists students as needed. Both co-teachers are actively engaged. B One co-teacher is the lead teacher and the other co-teacher observes, taking detailed notes and collecting data on the students and the teacher. B Co-teachers divide the content into separate stations through which students will rotate, with each coteacher leading a station of particular content. One Teach / One Assist A Whole Class One Teach / One Observe A Regrouping Station Teaching A Regrouping Alternative Teaching B A Regrouping B Parallel Teaching A Whole Class Team Teaching One co-teacher pulls a small group of students from the large group to reinforce or pre-teach curricular concepts. A B Co-teachers each instruct the content to half of the students in the class. Both co-teachers are presenting the same information. However, the student to teacher ratio is smaller. Both co-teachers are equal in the coplanning and presentation of material. Co-teachers may take turns presenting the content or present it together with each person building off what the previous co-teacher just stated. COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING Appendix C Co-Planning Checklist Week of ________________ Co-Planning with _________________________ Standards Did we… ____ Identify the standard of focus ____ Identify the students’ learning goals / objectives Assessment Did we… ____ Identify the assessment that assesses the standard ____ Modify assessment to meet the needs of all learners Homework Did we… ____ Identify homework ____ Modify or differentiate to meet the needs of all learners Accommodations / Modifications Did we… ____ Identify how to meet the needs of all learners ____ Did we address IEP goals Co-teaching Model Did we… ____ Identify the specific co-teaching model for instruction ____ Did we discuss the instruction with the co-teaching model identified 26 COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING Appendix D 27 COLLABORATION AND CO-TEACHING Appendix E 28