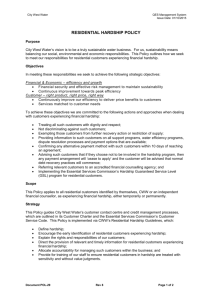

The material wellbeing of New Zealand households using non

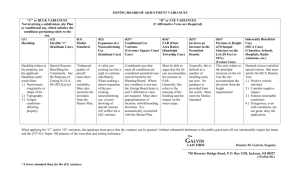

advertisement