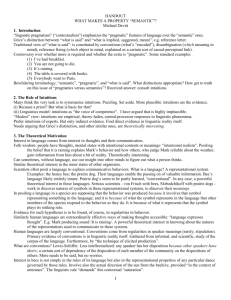

Here

advertisement