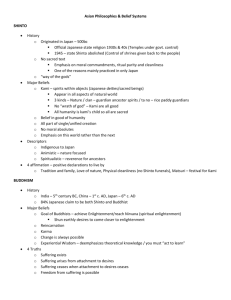

Shinto

advertisement

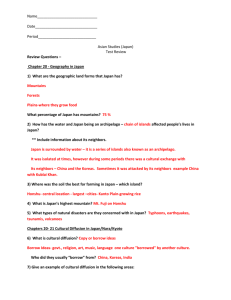

Shinto Our final look at belief systems outside the Judeo-Christian tradition takes us to Japan, where we will briefly look at the indigenous religious beliefs of Shinto. The word “Shinto” comes from two Chinese words—shen, meaning “deity,” and dao, meaning “the way.” Archeologists and historians believe that Shinto has existed in Japan since at least several centuries BCE, since they have found evidence that the ancient Japanese acknowledged the sacred presence and power of numerous beings called kami, “high or superior beings.” Until the middle of the 6th century CE (about the time of Muhammad) the Japanese people evidently did not think of their ancient religious traditions as a separate system. So organically integrated were those traditions with their entire culture and heritage that worship of the kami was largely assumed as the Japanese way. Only with the arrival of Buddhism, called in Japanese (butsu-do) “the Way of the Buddha,” did it become necessary to give their indigenous beliefs and practices a name to distinguish them from the imported tradition of Buddhism. Unlike many other major traditions, Shinto had neither a founder nor a single foundational figure who represented concrete historical origins. In many ways, Shinto is as old as Japan itself, just as Hinduism is as old as India. Two of Shinto’s earliest foundational documents recount the story of the divine origins of Japan and its people. The basic myth goes like this: In the beginning, heaven and earth were as one, positive and negative, unseparated. In a primal egg-like mass dwelt the principles of all life. Eventually the purer, lighter element rose and became heaven while the heavier descended and became earth. A reed-shoot grew between heaven and earth and became the ”One who established the Eternal Land.” After many eons of time, two kami were formed by spontaneous generation. Descending to earth on the Floating Bridge of Heaven, Izanagi (Male force) and Izanami (Female force) came into the world. Izanagi stirred the oceans depths with his spear and created the first lands. On the eight Japanese islands the union of Male and Female created the mountains and rivers, and 35 other kami. Last to be born was Fire, the kami of heat, who burned his mother during his birth. Izanagi slew Fire with his sword, creating several additional kami in the process. Izanami (the Female) fled to the underworld, the Land of Darkness, desperate to prevent her husband from seeing her corrupted (burned) state. When the Male followed and lit a fire so he could see, she chased him out and blocked his entrance to the Underworld. Returning to the surface, the Male immediately purified himself ritually, ridding himself of the underworld’s pollution. Corruption from his left eye formed the sun goddess Amaterasu, who rules the High Plain of Heavens, and from his right eye, Tsukiyomi, the moon, whose province is the oceans. From his nostrils he created the storm kami, Susanowo, Withering Wind of Summer and ruler of the Earth. Susanowo soon made trouble for his sister, the Sun, who took refuge in a cave. Needing the sun to return, the kami discussed how they might entice her from her cave. At length they resorted to enlisting the Terrible Female of Heaven to dance and shout to arouse Amaterasu’s curiosity. They then offered her blue and white soft offerings, a mirror, and a bejeweled Sakaki tree. She finally came out of her cave and sent her grandson Ninigi to rule the world. Sent down from heaven to establish order and bearing three precious symbols—the curved jewel, the sword, and a mirror (that even today are the symbols of Japanese Imperial power), “the august grandchild” landed in southeastern Kyushu. His son, Jimmu Tenno, in turn became the first human emperor at age 45, on February 11, 660 BCE. Jimmu Tenno, as the first emperor, enlarged his domain, set up his capital near the modern city of Osaka, ruled for over 100 years, and created the Japanese imperial dynastic line (which still exists today). At its core, the Way of the Kami enshrines profound insights into the sacred character of all created nature. Shinto calls people to a deep awareness of the divine presence in all things, to the challenge of personal and corporate responsibility for the stewardship of the world that is home, to unending gratitude for all that is good, and to a willingness to seek purification and forgiveness for humanly inevitable but avoidable lapses. Observe worshipers at a Shinto shrine and there can be little doubt of the sincere devotion that moves so many people to prayer and ritual expression of their beliefs. Religious studies scholars have increasingly come to appreciate the genuinely religious qualities of Shinto. Occasionally criticism still surfaces that Shinto is so much a part of ordinary Japanese life that it is really a set of cultural beliefs and practices rather than a religious tradition. Some critics base their conclusion on polls of the Japanese public that seem to suggest widespread apathy about religious issues. Decreasing numbers of people are willing to identify themselves as adherents of any religious tradition, including Shinto. Other critics note that even Japanese who do consider themselves active participants in a Shinto-based community are likely to claim they are Buddhist as well. Some point to Shinto’s concern with the ordinary, the everyday, the natural world that surrounds us, and its lack of interest in transcendent mystery. Shouldn’t a religious tradition be more invested in turning people’s attention to a world beyond this one? In fact, these are among the distinctive aspects of Shinto and the basis of its unique contribution to our world. Shinto offers insights into the inherent divine quality of the simplest things, of the beauty hidden away in life’s nooks and crannies. Shinto tradition discerns innumerable causes for profound gratitude to the powers beyond the merely human that make life itself possible. Shinto may not be celebrated for producing sophisticated schools of theological speculation, but it undoubtedly possesses many characteristics that identify it as a religious tradition. So is there a Shinto creed? Shinto beliefs, like Daoism, have never been reduced into a concise formal summary statement. If one were to produce a brief Shinto creedal affirmation it might go something like this: “I believe that sacredness surrounds me, that it pervades all things including my very self, and that the all-suffusing divine presence is ultimately benevolent and meant to assure well-being and happiness for all who acknowledge it and strive to live in harmony with it.” All religious traditions are oriented in varying degrees to two great inseparable realities—truth and power. Some , such as the Abrahamic traditions—Judaism Christianity, and Islam—tend to lean towards truths that human beings cannot discern without direct help from the source of the truth itself. Others, such as Daoism, focus more on teaching believers how to discern and benefit from the source of power. Shinto is far more concerned with power than with truth…which is greatly oversimplified, but it means that the power of the divine and its implications are the only important truths. Where and how do humans have access to those truths? Preeminently through the marvels of nature, including the human. Shinto’s deities do not reveal a message otherwise inaccessible to mortals, as in the case of the Abrahamic faiths. They do, however, disclose to anyone who reflects on his or her life with a clear mind and heart all the truth human beings need. Today, there are more than 80,000 Shinto shrines that are scattered all over the Japanese islands. There deities are worshiped and rituals are still performed according to the general patterns established by the Japanese state for all shrines in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Shinto is probably the world’s most ecologically attuned religious tradition. Divine energy saturates all of creation and is thus cause for reverence and wonder. Shinto is very optimistic in its outlook about life in this world, and it teaches that when humans are in harmony with nature, all persons and all things flourish. So there is no serious distinction or incompatibility between the physical and the spiritual, the human and the divine. Individuals take second place to the needs of society as a whole; as a result traditional Shinto philosophy doesn’t reflect in depth about the self apart from the collective. Above all, humans are children of the kami whose natural birthright is to benefit from nature’s gifts. Society and family, as well as nature, are the wellsprings of life. Acknowledging one’s ancestors keeps healthy the link between individual and society because it keeps alive the continuity of the Japanese heritage. Shinto begins with the conviction of innate human goodness and that the world is good. When evil takes over, it isn’t because of some inherent or inherited human tendency. Evil enters the world from outside, brought by evil spirits. These affect human beings in a similar way to disease, and reduce our ability to resist temptation. When human beings act wrongly, they bring pollution and sin upon themselves, which obstructs the flow of life and blessing from the kami. Evil advances whenever humans lose their concentration on life at its simplest, most basic level. In Shinto, an ethical person is one who makes choices unspoiled by ulterior motives. Purity of intention is more important than any specific set of commands or prohibitions. The overall aims of Shinto ethics are to promote harmony and purity in all spheres of life. Purity is not just spiritual purity but moral purity: having a pure and sincere heart. Purified of all ill intent, the mind and heart are illuminated through intimacy with the divine. Shintoists don’t evaluate their actions in terms of whether they will reap reward or suffer punishment as a consequence. Rather they think of how their actions might affect the life of the community here and now. How does one know if they have crossed a moral divide? Shame is a very powerful index of morality in the Shinto tradition. Any breach of social contract brings shame and one must seek forgiveness through purification. Shinto, like Buddhism, is very much what is called a world-affirming tradition. When devotees worship at a shrine the mood is generally solemn and reverent, but at festivals there is a great sense of joy and exuberance. At such celebrations there is little doubt that at the heart of the Shinto tradition there is a delight in the everyday world and a conviction of the inherent goodness of creation. In Shinto, salvation is not a question of deliverance from the present human condition into a realm beyond. Shinto teaches that the solution to the human predicament is just the reverse; sincere worshippers welcome the kami into the world of everyday concerns. Salvation therefore means making the ordinary sacred, so that life here and now becomes the best it can be. There are "Four Affirmations"in Shinto: 1. Tradition and the family: The family is seen as the main mechanism by which traditions are preserved. Their main celebrations relate to birth and marriage. 2. Love of nature: Nature is sacred; to be in contact with nature is to be close to the Gods. Natural objects are worshipped as sacred spirits. 3. Physical cleanliness: Followers of Shinto take baths, wash their hands, and rinse out their mouth often. 4. "Matsuri": The worship and honor given to the Kami and ancestral spirits. Ancient tradition talks of another world, a realm beyond this one, called the High Plain of Heaven…a happy state overflowing with life and richness. There is also a netherworld, a most unpleasant place called the Land of Darkness…ruled by death, that land is filled with wretched pollution and impurity. Most people today do not believe that the dead end up in one or the other of the realms beyond this world. Nevertheless, certain fundamental criteria determine whether an individual spirit will be content or disgruntled after death. These include the ethical quality of one’s life and one’s attentiveness to avoiding the impurity attached to improper behavior. The role of Shinto in Japanese history is twofold: its position with the royal house of Japan and its association with the Samurai tradition. Japan’s fabled Samurai warriors did have important connections to Shinto, but the fundamental Samurai belief in bushido (the Way of the Warrior) wasn’t based on Shinto, it was based more on Confucianism and Buddhism. But part of the Samurai code of ethics revolved around patriotism and devotion to ancestral kami, including loyalty to the emperor who was descended from the sun goddess. The most famous and one of the most important kami is Hachiman, the kami or god of war. Many Samurai included a devotional prayer to Hachiman before battle. Today, nearly half of all Shinto shrines in Japan are devoted to Hachiman. From the Meiji Period (1868) until the end of WWII, the emperor was considered a kami and was the chief priest of Shinto, and even though throughout much of Japanese history the emperor didn’t have much real power, as the chief priest of the native faith he commanded unquestioned loyalty and respect, a position the emperor still commands.