Genetics as a new form of identity and affiliation. Recognizing the

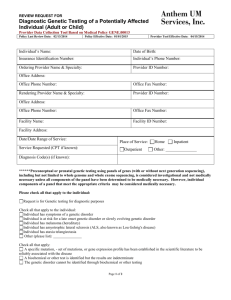

advertisement

Genetics as a new form of identity and affiliation. Recognizing the need for privacy I am interested in the question what Genetics and the knowledge of gene-functioning and gene-effects mean to so called ordinary people. To those who are not scientists or experts but persons concerned and affected, f.e. those who undertook genetic testing and received troubling results or those who get informed by family members that new genetic information came up through genetic testing which might effect them as well as their siblings and their children. How do people understand genetic information? How do they adjust to it? What does it mean to them? What does it mean for them? Asking such questions means to refer to empirical data of micro level every daycommunication within families, with insurances, at the workplace and in communication between doctors and patients. Looking at this every-day-communication also means to consider the societal and cultural circumstances and the social, institutional, legal and normative contexts of Genetics that are different in different countries. In Germany, where I do research, Genetics are located in a medical field that offers health insurance for all citizens based on a system of contributory financing for the majority of citizens. Hospitals and medical offices are run as private enterprises which are strictly regulated by governmental laws that demand rights of equal treatment and freedom of doctor’s choice. Ethically framed by the idea of tolerance towards people who are ill, and the claim to grant an autonomous life for people being sick or disabled, Genetics have always been a point at issue. Political and ethical debates revolve around the advantages and dangers of genetic knowledge. What is the individual and collective benefit of knowing a person’s genetic make up? To what extend do Genetics help to prevent illness? To whom does genetic knowledge belong? Is it private or common knowledge? Concerns about misuse and abuse of genetic information and about disadvantages and discrimination possibly going along with genetic knowledge were broadly discussed. In 2003, the case of a young teacher who was denied the status of a civil servant (which implies maximum job security) created a big stir in Germany. She herself – the teacher – did not show any symptoms of sickness but her father had fallen ill because of the hereditary Huntington disease and her employer took this as a reference for her problematic health condition and refused to accept the woman as a civil servant (Paslack/Simon 2005: 124). This case instigated a broad public discussion on how to protect people from a discriminatory usage of genetic information. Finally, in 2010, a legislation - the so called Genetic Diagnosis Act was implemented that administers the use of genetic information and introduced genetic education and genetic counselling in the procedure of genetic tests and prenatal genetic check-ups. Further more, the Genetic Diagnosis Act also aims at guaranteeing a right of informational self-determination – meaning: genetic information belongs to the person and he or she has the right to control the distribution of his or her genetic information. These specific cultural contexts and societal regulations create a certain reality in which the handling of genetic information and the meaning of the genetic information is enacted by individuals. Or to put it more philosophical and more abstract: The category “Genetic” becomes significant and important through two vectors. One is the vector of labelling from above, from a community of experts – like scientists, legal experts and politicians - who create the reality of the current “age of Genomics”. Different form this is the vector of the behavior of the person labelled as being “genetically at risk”, which presses from below, creating a reality that experts must face as well. I would like illustrate these two vectors by looking more closely at the example of every day interaction with Cystic Fibrosis. This genetic disorder is most common among Caucasians; 4% of people of European descent carries one allele for CF. The World Health Organization states that "In the European Union, 1 in 2000 - 3000 newborns is found to be affected by CF". In Africa CF shows in 1: 17.000 people, in Asia it is even more seldom. It is estimated that in Asia only 1 amongst 90.000 is effected by this disease. So, Cystic Fibroses is an example of the correlation between „Ethnicity and Genetics“. But beyond it’s ethnic specificity, CF points to a characteristic of many forms of genetic disorders. Namely, the conditional probability which troubles the so called „persons at risk“ and that shapes their understanding and their handling of the genetic information and it’s impact. Doing so, I am using empirical data from a study on „Genetic Discrimination in Germany“ – Thomas Lemke will tell you more about this tomorrow – I will not go into this any further (questionaire as well as on semi-structured interviews with persons effected by four different genetically based diseases). Enacting genetic information of Cystic Fibrosis Cystic fibrosis was first recognized in the 1930s. Difficulty breathing is the most serious symptom including lung- and sinus infections, poor growth and infertility. CF is caused by a mutation in the gene for the protein cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). This protein is required to regulate the components of sweat, digestive fluids, and mucus. Most people without CF have two working copies of the CFTR gene located at chromosome No 7, and both copies must be missing for CF to develop, due to the disorder's recessive nature. The most common mutation, Delta F508 accounts for two-thirds of CF cases; however, there are over 1500 other mutations that can produce CF. In our research we interviewed parents who either are carriers of the mutation or who are worried about having a sick child because CF appeared in the extended family circle. They reported to us how they became „persons at risk“ and how this changed their self-perception and their private and intimate life. There are two institutions that significantly organize this passage: Genetic Counseling and pregnancy counseling with special prenatal diagnostics. From the visitor’s perspective genetic counseling confronts the parents with information that is difficult for them to understand and to deal with. They get informed about their personal risk for transmitting CF to a child. To give an example: Mr. and Mrs. Jahn, parents of a healthy daughter, visit a Genetic Counselor because the sister of Mrs. Jahn’s gave birth to a baby that died due to CF at the age of six months. Their personal risk evaluation sounds as follows: Mrs. Jahn is a carrier of the CF-gene with a probability of 1:2 because her sister must have the gene and because statistically seen siblings share half of genetic endowment. Mr. Jahn who does not know of any CF-Symptoms in his family tree has the average risk of Europeans, that is 1:25. Assuming that both of them carry the gene, there is a 1:4 chance to pass it on to the child because of the recessive character of the CFmutation. The calculated risk of Mrs. And Mr. Jahn to have a child with CF is therefore 1:200. For Mr. Jahn this does not sound troubling. He says: „That means that 199 children would be healthy“. But Mrs. Jahn expresses her wish for more information and more precise information. The counselor offers a genetic diagnosis, a so called „genetest“. He explains that there are around 1500 different mutations causing CF and that a gene-test detects around 70% of mutations. A Gene-test of Mrs. Jahn would possibly verify her status as a risk-holder but would not be able to exclude her from the group risk-carriers because the mutation of the dead baby is unknown and because of that there is no possibility to locate a particular mutation. So, what a gene-test would do is to raise or to minimize the personal risk evaluation of Mrs. and Mr. Jahn. Furthermore the counselor explains that in case that Mrs. and Mr. Jahn both had a gene mutation and would send it on to a fetus it would be difficut to predict the degree of severity of the child’s illness. Some children with CF die within the a few years, other grow up quite normal and realize as adults that they are not able to conceive or to bear children. Others are very weak and in the need of medical care during all their life. For Mr. and Mrs. Jahn it was a puzzling experience to visit a Genetic Counselor. The information they received tainted their further thinking and conversation. They told us how they reflected their new state for being, how they tossed their thoughts back and forth. Their concerns circled around the questions: What is the probabilistic benefit of the new genetic information? Is Genetic information too broad, too unspecific for individuals? - Doctors treat individuals - Geneticists do risk calculation on populational scale. How does this fit together? They felt uncomfortable because the genetic information interfered with their realm of privacy and intimacy and put an emphasis on them to get active. But they did not have a clue of the consequences to draw. They felt the need to fit a new category, to behave like people being genetically at risk and to do this responsible-minded and carefully. The experience of Mr. and Mrs. Jahn is a part of a process that the Canadian philosopher Ian Hacking called „making up people“. Following Hacking one could say that making up people changes the space of possibilities of personhood. Genetics create a new way to be a person and the very role the new genetic model entices people to adopt is to adress to the new naming and what that entails. For the Jahn-family this meant to respond to the new notion of genetic responsibility. After finding out about Mrs. Jahn’s carrier status, Mr. and Mrs. Jahn discussed their reproductive options in a new light of obligations and responsibilities. To assess and to manage their family’s health they refused to structure their reproductive choices solely on risk estimates and diagnostic tests. The Jahn-Family as well as one half of the parents carrying the CF-mutation in our study planned a non-mediated pregnancy, willing to risk having an affected child. They talked about their reproductive decisions primarily in relation to a moral framework that values active parenthood and honours differences. Or as Mrs. Jahn puts it: „And as far as I am concerned, a child with a disability is no less of a worthy person to live“ and she adds: „We decided that it was important for our daughter to have a sibling, regardless, so that they would have each other. That’s kind of how we looked at it. So we decided to do that“. Mrs. Jahn, whose second child, was born sick with CF, framed her and her husband’s decison to have another child as a conscious evaluation of what was best for their family: giving their daugher a brother or a sister. The women of our study who know about their risk-status and continued to have children built up a framework of values of motherhood and family as integral to their understanding of being responsible. This frame extended beyond risk calculations of transmitting a genetic disorder. In rejecting a prescriptive construction of themselves as genetically at-risk individuals, these women instead emphasized their social role as mothers and advocate for love and appreciation of children regardless of their genetic status. They reject a value distinction between those with disabilities and those without and heightened awareness of their own parenting strengh and limits. On the contrary, the other half of mothers in our study chose to stop reproducing when they found out about their carrier status. They consciously talked about this decision as a „responsible“ one, albeit one that limited their invisioned family and family plans. They talked about the complicated tensions that arise from managing their own genetically-at-risk status, that is: feeling sad, emphasizing the amount of work that comes along with having a CF-child, what made them realize that they are not able to put up with a second sick child. Others expressed tensions because of their decision to select against children like the ones they already had. Some of them voiced a sense of being censured and criticised if they passed on a gene known to cause a severe disease. Others express unease about the possible societal consequences of such genetic testing-based choice over time. This concern led them to envision a future in which individuals increasingly base reproductive decisions on their potential genetic predispositions for disorders, and in so doing create a society where „special children“ are not wanted. Alltogether, these reports on understanding and enactments of persons being a genetically at-risk actor illustrate the complexities, contradictions and ambivalences embedded in the experiences of undergoing genetic testing, genetic counselling and reproductive decisions. They also show that whether or not to have children is not a straightforward decision based on circumscribed notions of genetic risk and genetic responsibility, but rather involves a complex negotiation of personal desires, family values and diversity, familial work capacities and financial constraints. Those who have experience with a specific genetic condition take their own decisions to pass on this gene due to a variety of values and because of personal likes and dislikes as well as abilities. To acknowledge these differences means to recognize and to grant privacy, a realm of the private-sphere in which the distinctiveness of being a person genetically at-risk may live comfortably.