social psychological approaches to explaining aggression

advertisement

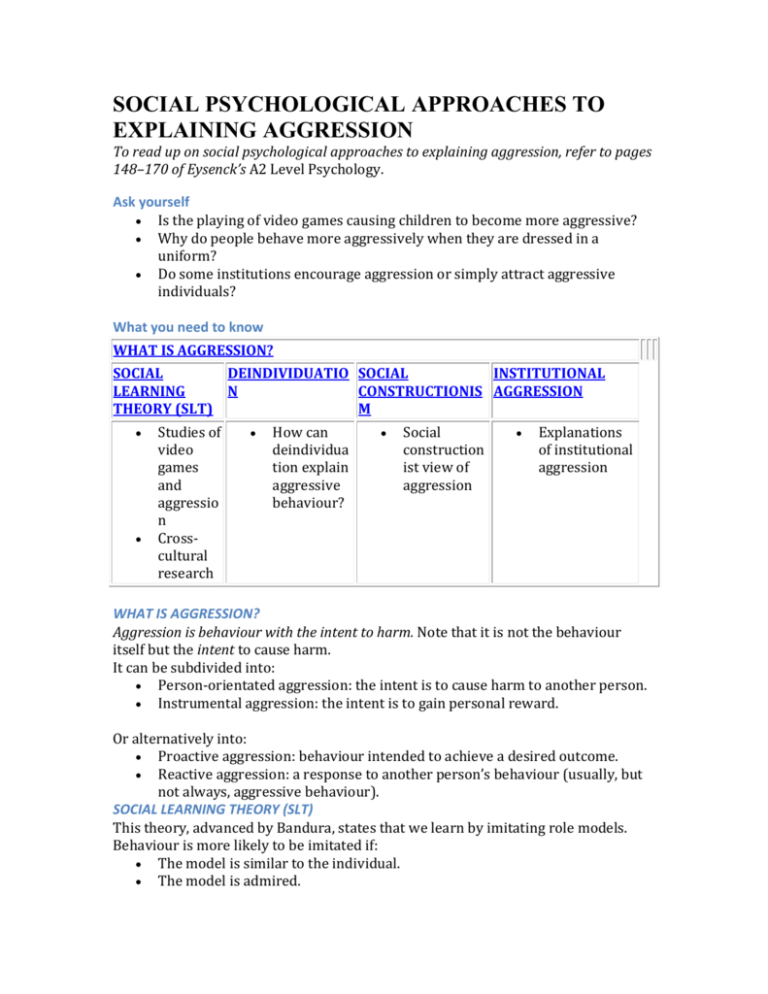

SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGICAL APPROACHES TO EXPLAINING AGGRESSION To read up on social psychological approaches to explaining aggression, refer to pages 148–170 of Eysenck’s A2 Level Psychology. Ask yourself Is the playing of video games causing children to become more aggressive? Why do people behave more aggressively when they are dressed in a uniform? Do some institutions encourage aggression or simply attract aggressive individuals? What you need to know WHAT IS AGGRESSION? SOCIAL DEINDIVIDUATIO SOCIAL INSTITUTIONAL LEARNING N CONSTRUCTIONIS AGGRESSION THEORY (SLT) M Studies of video games and aggressio n Crosscultural research How can deindividua tion explain aggressive behaviour? Social construction ist view of aggression Explanations of institutional aggression WHAT IS AGGRESSION? Aggression is behaviour with the intent to harm. Note that it is not the behaviour itself but the intent to cause harm. It can be subdivided into: Person-orientated aggression: the intent is to cause harm to another person. Instrumental aggression: the intent is to gain personal reward. Or alternatively into: Proactive aggression: behaviour intended to achieve a desired outcome. Reactive aggression: a response to another person’s behaviour (usually, but not always, aggressive behaviour). SOCIAL LEARNING THEORY (SLT) This theory, advanced by Bandura, states that we learn by imitating role models. Behaviour is more likely to be imitated if: The model is similar to the individual. The model is admired. The model receives reinforcement for the action. The individual has low self-esteem. The individual is dependent on others. Behaviour such as aggression can also be affected by vicarious reinforcement and vicarious punishment. This refers to reinforcement and punishment that has an effect on the individual but is received indirectly rather than directly. If the model is reinforced for their actions, the individual is more likely to imitate the behaviour. If they are punished for it, this will decrease the likelihood that behaviour will be imitated. The ARRM model is a useful mnemonic for remembering the conditions under which behaviour is likely to be imitated (and therefore explaining the conditions under which aggression is copied): Attention—the person must pay attention—aggressive behaviour is usually noticed. Retention—the individual retains the information for future use. Reproduction—the individual must be capable of copying the behaviour. Motivation—the individual must be motivated to imitate the behaviour. If they have received reinforcement or seen others reinforced for being aggressive (for example, by getting what they want) they will be motivated to imitate it. The converse is true with respect to direct and vicarious punishment. RESEARCH EVIDENCE FOR SOCIAL LEARNING THEORY Bandura, Ross, and Ross (1961, see A2 Level Psychology page 150) conducted a classic study on imitation of aggression. Children aged 3–5 years were taken one at a time into a room where they sat at a table on which there were lots of attractive toys. An adult model sat at another other table on which there was a variety of toys, including a Bobo doll. Half of the children were in the aggressive (experimental) condition in which the model attacked the Bobo doll using the same series of aggressive actions, including some unusual ones. Half the models were men and half were women. The other half of the children were in the non-aggressive condition. The researchers found that children in the aggressive condition reproduced a great many of the physical and verbal aggressive acts they had observed. In the non-aggressive condition, the children showed no aggression at all but simply played with the toys in a non-aggressive manner. Boys reproduced more physical aggression than did the girls but there was no difference in boys and girls with respect to verbal aggression. Boys were more likely to be aggressive if they had seen a male model rather than a female one, and girls were more likely to be aggressive if they had seen a female model rather than a male one. The results show strong evidence that children are likely to copy new types of behaviour that they would have been unlikely to produce otherwise. Bandura (1965) conducted similar experiments using films of aggression. An adult model was seen being aggressive but the ending of the film differed in three conditions. In one, the model was congratulated (rewarded). In the second, they were reprimanded (punished). In the third, there were no consequences. Children seeing the model reinforced or experience no consequences were significantly more likely to imitate the model than those who saw the model being punished. Walters and Thomas (1963, see A2 Level Psychology page 149) found that participants who had watched a violent scene chose to administer higher electric shocks to learners who gave incorrect responses than those who had not witnessed violence (no shocks were actually administered). This demonstrates disinhibition—the weakening of inhibitions against socially unacceptable behaviour. Patterson, DeBaryshe, and Ramsey (1989, see A2 Level Psychology pages 149–150) compared homes in which there was at least one aggressive child with those with no aggressive children. They used the term “coercive home environment” to describe the home from which the aggressive children came. The main features of such homes were: o Harsh discipline—little or no reinforcement for socially acceptable behaviour, physical punishment, shouting and teasing. o Lack of supervision. o Parental aggression, which provided role models for aggression. Studies of Video Games and Aggression Anderson and Dill (2000, see A2 Level Psychology page 151) conducted a series of studies using large numbers of college students and concluded that violent video games prime aggressive thoughts in the players that could transfer into real-life behaviour by the process of constructing and running aggressive scripts in the players’ heads. Weber, Ritterfeld, and Mathiak (2006, see A2 Level Psychology page 151), using fMRI scans, found that playing violent video games suppressed the emotional areas of the cortex. EVALUATION OF RESEARCH ON VIDEO GAMES AND AGGRESSION Lack of ecological validity. Playing video game in a laboratory does not reflect everyday behaviour. Demand characteristics. Participants may act in an unusual manner because they are being observed and may act in the way they feel they are expected to. Reflection of certain aspects of real life. Video games are exciting and involve people being successful and rewarded; they are also talked about, so they may be modelled to a certain extent on real life. Correlational designs do not show cause and effect. Some of these studies are correlational, so they cannot show that playing a violent video game causes aggression. It could be that aggressive individuals like playing these games. Empirical research does indicate cause and effect. Research using brain scans, such as Weber et al. (2006), does indicate that certain brain areas might be affected by playing violent video games, implying that there is some cause and effect. Cross-cultural Research Research on the amount and type of aggression shown in other cultures does help to highlight the degree to which aggression is learnt. If cultures are similar, it implies that biology is a stronger influence than learning through cultural norms. On the other hand, if cultures are very different, this implies that socialisation (i.e. learning) is important. Mead (1935, see A2 Level Psychology page 152) found great variation in aggression in different cultural groups: some were extremely aggressive whilst others were very peace loving. Although Mead has been criticised for exaggerating the extent of these differences, her research does support the role of social learning in aggression. Andreu et al. (1998, see A2 Level Psychology page 152) found that Japanese men were more verbally confrontational and aggressive than men in the USA. Bonta (1997, see A2 Level Psychology pages 152–153) discussed nonaggressive societies and found that beliefs and norms of co-operation and non-competitiveness were the key factors determining such behaviour in the majority of these societies. EVALUATION OF CROSS-CULTURAL RESEARCH Differences do support social learning theory. Cultural differences are likely to be due to learning rather than biology. The huge variation in the amount of aggression between cultures supports the learning explanation. Exaggeration of differences. It’s possible that Mead overestimated the extent of variation amongst cultures. Misunderstandings due to language barriers. It’s possible, especially with Mead’s study, that researchers are not familiar with the language of the cultures and that this leads to a lack of understanding of the culture. Biased sample of behaviour. Since most researchers spend relatively little time with each culture, they may not observe a representative sample of everyday behaviour. Demand characteristics. Because the people knew they were being observed, they may have changed their behaviour. Alternative explanations. It’s possible that evolutionary explanations offer a better explanation than SLT for some of the findings. For example, using verbal aggression can release and express anger without risk of physical harm. SLT alone cannot explain changes in types of aggression. Cultures often show changes in the amount of aggression they show over time. These cannot adequately be explained by SLT; changes in social norms over time are a more likely explanation. Under-estimation of role of biology. Aggression may be caused by biological factors such as testosterone (as considered later). http:// DEINDIVIDUATION Deindividuation involves the loss of personal identity and consequent personal responsibility when we become anonymous. It can occur when we are in a crowd or in a uniform. Research indicates that people are more inclined to be aggressive (and anti-social in other ways) when they are anonymous, so deindividuation can offer an explanation for some occasions when aggression occurs. Diener (1980, see A2 Level Psychology page 154) lists four consequences of deindividuation: Poor self-monitoring of behaviour. Reduced need for social approval. Reduced inhibitions against behaving impulsively. Reduced rational thinking. Deindividuation has been used to explain aggressive behaviour. It is argued that when people feel anonymous and unable to be identified, they feel less constrained by the norms of social behaviour and more able to act in an anti-social manner. Their actions become highly emotional, impulsive, and atypical. RESEARCH EVIDENCE FOR DEINDIVIDUATION Zimbardo (1973, see A2 Level Psychology page 154) showed how aggressively students behaved when playing the role of guards. He explained this in terms of deindividuation: the uniform (including mirrored sunglasses) hid their personal identity. Zimbardo also demonstrated that when female student participants wore name labels they were less likely to administer electric shocks than when wearing costumes and hoods. EVALUATION Deindividuation does not always lead to aggression. The prisoners in Zimbardo’s prison study could also said to be deindividuated as they were in uniform but they were not aggressive. There could be other factors causing aggression. In the prison study, the “guards” were instructed to render prisoners powerless so it could be this, not the deindividuation, that caused them to be aggressive. The particular uniform could have an influence. In the study of female students, the uniform resembled that of the Ku Klux Klan, which is associated with aggression. When participants were dressed as nurses, they were less aggressive than when not in any uniform. Crowding does not always cause aggression. The circumstances under which a crowd gathers can affect the degree of aggression. A crowd attending a concert may be less aggressive than a crowd of demonstrators or a football crowd. SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONISM Social constructionists believe that people impose subjective interpretations (or constructions) on behaviour (Gergen, 1997). When applied to aggression, the social constructionist approach makes the following assumptions: 1. Aggressive behaviour is a form of social behaviour and is not simply an expression of anger. 2. Our interpretation or construction of someone else’s behaviour as aggressive or non-aggressive depends on our beliefs and knowledge. 3. Our decision whether to behave aggressively or non-aggressively depends on how we interpret the other person’s behaviour towards us. RESEARCH EVIDENCE Blumenthal et al. (1972, see A2 Level Psychology page 158) found that, when asked to judge police action during student demonstrations, students judged the police to be far more aggressive than did members of the American general public. Conversely, student actions were more likely to be judged as aggressive by members of the public than by students. Brown and Tedeschi (1976, see A2 Level Psychology page 158) found that someone who initiated a hostile action was seen as aggressive, whilst someone who retaliated was not seen as aggressive. This demonstrates that people interpret actions according to social norms; in this case, the social norm that is acceptable to retaliate if provoked. Marsh, Rosser, and Harré (1978, see A2 Level Psychology page 158) studied violence by students in schools and concluded that this was a response to the belief that they had been “written off”; therefore they responded with anger. EVALUATION Support from everyday experiences. Everyday experience provides support for the fact that aggression is a form of social behaviour rather than always an expression of anger. Support from research. Studies such as that of Blumenthal et al. (1972) support the view that our judgement concerning whether or not someone is behaving aggressively depends on the constructions we place on behaviour. Support from research. Studies such as Brown and Tedeschi (1976) support the assumption of the social constructionists that our judgements are based on social norms. Exaggerates the extent of interpretation. Social constructionism overemphasises the role of constructions in people’s judgements of whether an act is aggressive. There are cases in which there would be virtually unanimous agreement that an act is aggressive. INSTITUTIONAL AGGRESSION Institutional aggression occurs when aggressive behaviour has become the norm in an institution, whether a prison, in the military, or elsewhere. Any explanation of the causes of institutional aggression must consider two alternatives to account for the cause of the aggression: the features of the institution or that certain institutions attract aggressive individuals. Features of the Institution—the Agentic State Milgram’s work (among others) has shown that ordinary people can do dreadful things to other people simply because of the power of the situation. As Milgram says, “it does not take an evil man to do an evil deed”. His work demonstrated that people will act aggressively if they believe that their actions have been approved by those in authority above them. The theory proposed by Milgram was that people move into an agentic state and do not feel responsible for their own actions. As you may recall from AS, an agentic state is a state of mind in which individuals believe they are acting for someone else; they are the other person’s agent, and do not have personal responsibility for their actions. This view therefore supports the first of the causes mentioned above, that it is features of the institution in which people are expected to obey orders, rather than the disposition of the individuals that can lead to institutional aggression. EVALUATION OF THE AGENTIC STATE AS AN EXPLANATION FOR INSTITUTIONAL AGGRESSION Supporting studies lack ecological validity and mundane realism. Milgram’s studies involved very artificial situations, unlikely to occur in everyday life, so they do not necessarily reflect how people would ordinarily behave. Nevertheless, it is fair to say that some of Milgram’s other work, based on everyday experiences, did have ecological validity and people still behaved obediently even if it meant hurting someone. Milgram’s participants did not appear to be in an agentic state. Some psychologists argue that the fact participants were in an obvious state of extreme distress does not support the view that they were in an agentic state. Alternative explanation—situational factors. Zimbardo argues that situational factors can have a huge effect on aggressive and anti-social behaviour. For example, he argues that circumstances of a prison or other institution can greatly affect the amount of aggression shown. If aggression and bullying are the social norm, others will follow. The converse is true: a culture of non-violence encourages non-aggressive behaviour. Features of the Institution—Social Identity Theory Tajfel and Turner (1979, see A2 Level Psychology page 162) proposed a theory of prejudice known as social identity theory, which includes an explanation of how people may develop aggressive attitudes and behaviours towards members of other groups. Social identity theory argues that people of low self-esteem tend to divide the world into ingroups and outgroups. They consider the ingroup to be superior in some way to the outgroup (perhaps more aggressive or more athletic). They exaggerate the differences between the ingroup and outgroup and develop a rivalry between the two groups. This can sometimes lead to violent intergroup conflict. EVALUATION OF SOCIAL IDENTITY THEORY AS AN EXPLANATION FOR INSTITUTIONAL AGGRESSION Supporting research. Research has shown that intergroup prejudice is developed from a very young age (Tajfel & Jahoda, 1966). Good explanatory power. There are clear-cut ingroups and outgroups within some institutions (e.g. prisoners and guards) and if the outgroup can clearly be blamed for some actions (such as committing a crime) it offers a rationale for them to be treated harshly by the dominant ingroup. The theory can explain this. Groupthink adds further explanatory power. Groupthink involves reaching agreement within a group without too much analysis and discussion and often leads to polarization of the ingroup and outgroup, with extreme negative views of the outgroup. There is supporting evidence. There is some biological evidence which implies that agreeing with one’s own group can be less stressful than challenging it, which helps to account for why the tendency to think in terms of “us” and “them” and become aggressive might be very plausible (believable). This could have happened in Zimbardo’s prison study and in some real-life institutions (Berns et al., 2005, see A2 Level Psychology page 163). Challenge from other views. Janis (1972, see A2 Level Psychology page 163) believes that there are eight factors that need to operate before groupthink can lead to extreme aggression and that social identity theory is too simple an explanation to account for this type of thinking and the resultant behaviour. DYSFUNCTIONAL POWER SYSTEMS THEORY This theory argues that the organisation of power within an institution allows individuals within that institution to become aggressors. This theory places responsibility on the managers of the institution. Factors that appear to lead to abuse are based on structural faults in how an institution is organised. These faults include: Isolation of a group from the outside world and removal from everyday life; an inward looking group. A very close cohesion and agreement on ideology. A provocative situation with external stressors causing high stress and moral dilemmas. A resultant view that everyday norms and values are not seen as relevant in this workplace and alternative norms and values replace them. Dehumanisation of the outgroup. RESEARCH FINDINGS Zimbardo (2007, see A2 Level Psychology page 164) points to a USA scam, known as the strip-search scam. This scam involved decent people who became persuaded to act in a dreadful fashion. Hersh (2004, see A2 Level Psychology pages 164–165) exposed aggression and abuses at a prison named Abu Ghraib in which horrendous acts of abuse were perpetuated by US soldiers against Iraqi prisoners. The characteristics listed above applied in that prison with the result that soldiers (both men and women) who were normally decent people (according to Zimbardo) behaved in very indecent ways. EVALUATION Necessary institutional conditions don’t always apply. The institutions in which the strip-search scam occurred were fast-food restaurants. This type of institution does not have the characteristics suggested by this theory (isolated from the outside world and so on). Other features of the situation, such as the stress of trying to cope with a supposed policeman, and the compliance that employees are expected to show, could better account for it. Support from historical events. The Holocaust, which involved extreme aggression, does fit with the characteristics. The guards were isolated, the prisoners dehumanised; there was a strong ideology and huge stress. Support from more recent real-life events. Zimbardo (2007) and Hersh (2004), commenting on Abu Ghraib, report that the management of the US soldiers was organisationally very poor indeed. Some of the conditions of the theory did apply (e.g. isolation, dehumanisation, extremely stressful conditions). In addition, there was a breakdown of discipline and encouragement to abuse in order to “soften up” prisoners so they gave vital information. There is evidence for dispositional traits being responsible for aggression. Not all institutional aggression appears to be caused by the organisation and/or situation. There is a small minority of extremely aggressive football fans who have respectable professional careers but who join football crowds not to watch football but in order to be aggressive and racist—see last section). They use football events as opportunities to indulge in acts of violence. SO WHAT DOES THIS MEAN? Social psychologists argue that much of our aggression stems from what we have learnt. They propose that significant people, such as parents, peers, older siblings, and media stars, provide us with role models that shape our behaviour. Hence the cultural and sub-cultural differences in the amount and type of aggression shown in different sections of society and across cultures. Social constructionists argue that our interpretations of events affect whether we view acts as aggressive; we do not make objective judgements based on “facts”. Institutional aggression may arise from a combination of factors. The most dangerous ones involve close-knit, isolated groups united by ideology who dehumanise certain groups and justify treating them with extreme cruelty. The social approach to aggression has provided insightful explanations of the roots of aggression but does, perhaps, underestimate biological influences. It is these to which we now turn our attention. OVER TO YOU 1. Describe and evaluate two explanations of institutional aggression. (25 marks)