Central Retinal Vein Occlusion - Pennsylvania Optometric Association

advertisement

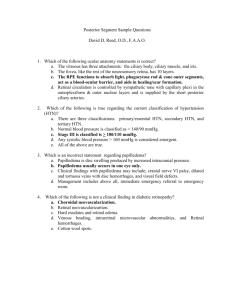

JOSEPH SOWKA, OD, FAAO FT. LAUDERDALE, FL jsowka@nova.edu ALAN G. KABAT, OD, FAAO MEMPHIS, TN alan.kabat@alankabat.com ANDREW GURWOOD, OD, FAAO PHILADELPHIA, PA agurwood@salus.edu Course Description: Case presentations provide a springboard for in-depth discussion of several challenging posterior segment conditions. Emphasis is placed on understanding the presentation, pathophysiology and management of the various clinical entities. Learning Objectives/Outcomes: At the conclusion of this course, the attendee will be able to: 1. Identify the pathophysiology, clinical presentation and management of central retinal vein occlusion; 2. Identify the pathophysiology, clinical presentation and management of central retinal artery occlusion; 3. Identify the pathophysiology, clinical presentation and management of diabetic retinopathy; 4. Identify the pathophysiology, clinical presentation and management of age-related macular degeneration; 5. Discuss the newest pharmacologic entities used to manage choroidal neovascularization; 6. Identify the pathophysiology, clinical presentation and management of central serous chorioretinopathy. CENTRAL RETINAL VEIN OCCLUSION Thrombotic phenomenon: Properties of the blood and central retinal vein act in concert to cause thrombotic occlusion. Causes partial or complete blockage of venous return Vein inflammation Vascular flow and/or vessel wall abnormalities stimulate vein thrombosis Hypercoagulability states, elevated viscosity, and systemic states of decreased thrombolysis promote thrombus formation. (i.e., changes in blood constituents) Turbulent blood flow causing thrombus formation at lamina Laminar constriction site is the nidus for occlusion. Intraluminal pressure of the vein decreases, rendering it susceptible to collapse. Compression by an arteriolosclerotic CRA further affects flow and thrombus formation. CRV and CRA share common sheath passing through lamina cribrosa. External factors such as increased IOP in POAG and papilledema (causing increased pressure in the optic nerve sheath) may cause further compression and contribute to occlusion. Other factors that result in compression include: orbital tumor and abscesses, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and retrobulbar intranerve sheath injection. Systemic diseases influence thrombus formation through: External compression Primary thrombus formation (Antiphospholipid antibodies, hypercoagulable states, thrombogenic conditions) Degenerative or inflammatory disorders of the vein itself Central Retinal Vein Occlusion: Symptoms Blurred vision Loss of visual field Disturbances in visual field Photopsia, in rare cases Rarely asymptomatic Smaller occlusions (BRVO, HRVO) may be asymptomatic Central Retinal Vein Occlusion: Clinical Signs Dilated, tortuous veins Deep and superficial hemorrhages Disc edema Macular edema Posterior (uncommon) and anterior segment (more common) neovascularization Collateral vessels Pre-existing vascular anastomoses in vascular area Collateral circulation is present to some degree in all organ systems. The extent to which collateral circulation prevents ischemia depends upon the time frame of the occlusion and the extent of collateral circulation for that organ and that individual. Bypasses vascular bed occlusion Beneficial- does not leak NaFl on FA Larger caliber than neovascularization Most commonly involves a communication between the retinal veins and the choroidal veins in response to retinal vascular occlusion Collaterals of the disc are more common than in the retina for CRVO; other vascular occlusions are more likely to have retinal collateral vessels. Clinical Pearl: Acute CRVO may cause angle closure glaucoma due to hemorrhagic choroidal expansion. Central Retinal Vein Occlusion: Causes of Vision Loss Macular edema: this is the main cause of vision reduction in CRVO. Potentially reversible or treatable RPE atrophy: occurs secondary to chronic macular edema and results in permanent vision reduction. This is the reason that macular edema just can’t be left to persist indefinitely Macular ischemia: presents with severe, irreversible vision loss. This is often the cause when the vision loss is much more dramatic than the clinical picture. Retinal hemorrhage (common) Vitreous hemorrhage (rare) Tractional retinal detachment (rare) Neovascular glaucoma (common) in ischemic cases Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is released by hypoxic retina to stimulate growth of new blood vessels (neovascularization) VEGF is the source for edema and neovascular disease. It also destabilizes vascular membranes leading to fluid leakage and edema. Central Retinal Vein Occlusion: Non-ischemic (Perfused) Majority of cases (about 70%) Acuity >20/200- low risk for neovascularization unless converts to ischemic form Good prognosis 5-20% progress from non-ischemic to ischemic CRVO 83% of ‘indeterminate’ CRVO convert to ischemic CRVO over 4 months Over 3 years, 34% of perfused eyes progressed to ischemic CRVO Central Retinal Vein Occlusion: Ischemic (Non-Perfused) Minority of cases (about 30%) Acuity < 20/200- high risk for neovascularization Initial VA is typically count fingers Extensive superficial hemorrhages Multiple CWS Poor capillary perfusion (10 or more cotton wool spots or 10 DD capillary non-perfusion on fluorescein angiography) Turbid, orange, edematous retina Poor visibility of choroidal detail (+) RAPD Poor prognosis Very high risk of neovascularization or the iris and angle and a low/ moderate risk of disc/ retinal neovascularization. Central Retinal Vein Occlusion: Systemic Considerations Hypertension* Diabetes mellitus* Elevated homocystein levels* Cardiovascular disease (some studies feel that the CRVO pt. has no greater incidence of cardiovascular disease than age matched controls) Hyperviscosity syndromes: Hypergammaglobulinemia, paraproteinemia, hyperfibrinogenemia, cryofibrinogenemia Hyperviscosity states: Malignancy, paraproteinemia, nephrotic syndrome, chronic lung disease, Behcet's disease. AIDS: Infectious vasculitis Collagen vascular disease: Lupus and lupus-like diseases- Antiphospholipid antibodies, common in these diseases, interfere with endothelial cells and prevent interaction with platelets and anticoagulants, thus increasing thrombus formation. Primary antiphospholipid antibody syndrome Same reasons as collagen vascular disease, but phenomenon is primary entity This is the most common cause of CRVO in young healthy adults (under age 50). Very important Syphilis: Infectious vasculitis Sarcoid: Localized vein inflammation Polycythemia (hyperviscosity) Leukemia (blood dyscrasia-hyperviscosity) Autoimmune disease: Infectious vasculitis and antiphospholipid antibodies Oral contraceptive use (causes a potentially hyperviscosity state) Head injuries Carotid artery disease: Slow flow and increased viscosity Hyperlipidemia Mitral valve prolapse Migraine Pressure profusion abnormalities at ONH Retrobulbar compression Sickle cell disease (blood dyscrasia- hyperviscosity) - elevated hematocrit Increased erythrocyte aggregation Decreased plasma volume (causing increased viscosity and erythrocyte aggregation) *Most experts feel that only these conditions must be examined for in the typical elderly vein occlusion patient and that more detailed evaluations should be reserved for special cases such as bilateral cases or in patients who are young (<50 yrs). In younger patients, testing for antiphospholipid antibodies is important. Central Retinal Vein Occlusion: Management Fluorescein angiography: questionable usage. Not appropriate early in the course as fluorescein is blocked by extensive hemorrhage. Possible angiographic features include: Macular and retinal hyperfluorescence from edematous leakage o Decreased size of foveal avascular zone Hypoperfusion from retinal ischemia or blood blockage o Increase size of foveal avascular zone Delayed venous filling time Pupil testing Retinal photography Gonioscopy to rule out angle neovascularization IOP measurements Co-management with primary care physician to identify and treat any underlying systemic disease Referral to retinologist if NVD, NVE, NVI, NVG (for PRP), or macular edema develops. Results of CRVO Study- N and M studies: Prophylactic PRP to prevent neovascularization inappropriate; therapeutic PRP once neovascularization develops very effective Laser photocoagulation of macular edema (as for diabetic macular edema) not beneficial in cases of CRVO and hence not done Newest treatments: intravitreal injection of steroids and anti-VEGF drugs (Avastin, Lucentis) for macular edema. Stabilizes vascular membranes and reduces vascular permeability. Very effective (both for macular edema and neovascularization)- Avastin is off label use. EYLEA (aflibercept) is a recombinant fusion protein consisting of portions of human VEGF receptors 1 and 2. It is considered a VEGF-trap in that it causes VEGF to bind with it rather than retinal VEGF receptors and reduces retinal effects of VEGF May have higher affinity for VEGF-A, thus potentially more therapeutic effect and fewer injections CENTRAL RETINAL ARTERY OCCLUSION Central Retinal Artery Occlusion: Clinical Picture Painless, sudden loss of monocular vision Vision is count fingers to hand motion to no light perception Retinal edema causing white appearance to fundus Mean age is 60's Cherry red macula due to underlying choriocapillaris perfusion and lack of overlying structures within this area. Optic atrophy ensues eventually Central Retinal Artery Occlusion: Pathophysiology Etiology is typically emboli from carotid artery or heart lodging in central retinal artery at laminar constriction. Emboli of cardiac origin are more likely than emboli of carotid origin to cause artery occlusion Other possible etiologies: Giant cell arteritis (GCA) Intraluminal thrombosis\ Hemorrhage under atherosclerotic plaque Vasospasm Dissecting aneurysm Hypertensive arteriolar necrosis Circulatory collapse Central Retinal Artery: Heroic Treatment Paracentesis to reduce IOP and allow less compression on CRA to allow emboli to pass further. Carbogen Patient is hospitalized and breathes Carbogen 5-10 minutes every hour for 24 hours. Using pure oxygen is worse because there will be a reflex constriction of the blood vessels. Carbogen increases CO2 levels, which causes a rebound vasodilation. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy Some anecdotal success, but has to be done immediately and this is rarely possible Digital massage to transiently elevate IOP and have rebound IOP decrease and subsequent arterial dilation Breathing into a brown paper bag in order to increase blood CO2 levels. Fibrinolytic agents (clot-busters: urokinase, streptokinase) 1-24 hour window of opportunity Treatment vs no treatment: 1/4 line difference in Snellen acuity. Overall, heroic measures do not affect final visual acuity (only anecdotal success). If the cause is inflammatory thrombosis from GCA, these heroic measures will do nothing because there is no embolus to dislodge. Central Retinal Artery Occlusion: Systemic Considerations General atherosclerosis Arterial hypertension Diabetes Carotid atherosis Cardiac/ cardiovascular disease Giant cell arteritis Infectious endocarditis Cardiac valvular disease Rheumatic heart disease Mitral valve prolapse Mural thrombus after MI Atrial myxoma IV drug use Lipid emboli Pancreatitis Purtscher's retinopathy Head, neck, retrobulbar corticosteroid injections HZV Migraine Malignancy Trauma Hyperlipidemia Syphilis Mucormycosis Hemoglobinopathy Sickle cell disease Oral contraceptives Platelet and clotting factor abnormalities Systemic lupus erythematosus Antiphospholipid antibodies from lupus cause prolonged partial thromboplastin time Primary antiphospholipid antibody syndrome Polyarteritis nodosa Homocystinuria Pregnancy Optic disc drusen Prelaminar compression of CRA, leading to turbulence and thrombus formation Central Retinal Artery Occlusion: Complications CVA Myocardial infarction: main cause of death Low survivorship: 9 year mortality of 56% (compared to 17% in age matched group) Neovascularization uncommon because tissue abruptly dies, not slowly starves as in vein occlusions Central Retinal Artery Occlusion: Management Stat ESR/ C-reactive protein if over 60 years old Co-management with primary care physician to identify and treat any underlying systemic disease Internal medicine/ Cardiology referral Monitor for complications Q3mos Heroic measures generally not helpful DIABETIC RETINOPATHY Diabetic Retinopathy: Pathophysiology Thickening of capillary basement membrane (which may lead to closure) Prevents pericytes from being in contact with endothelial cells May increase leakage potential Pericyte dropout Increases leakage potential Leads to breakdown of blood-retina barrier Focal loss leads to bulging of capillaries and microaneurysm formation Weakened capillaries Allows for microaneurysm formation and leakage Dot & blot hemorrhages- inner nuclear and outer plexiform layers- deep Flame shaped hemorrhages- NFL (superficial) Macular edema: leaking aneurysms and capillaries in macular area This is the most common cause of visual reduction in diabetic retinopathy. However, this is not the most common cause of severe, irreversible vision reduction (that would be anterior and posterior segment neovascularization with subsequent neovascular glaucoma and tractional retinal detachment, as well as macular ischemia) Fluid leakage and lipid accumulation: exudate Capillary closure: hypoxia Leads to intraretinal microvascular abnormalities (IRMA), cotton wool spots (CWS), neovascularization, vitreous hemorrhage, tractional retinal detachment and release of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) which increases vascular permeability and retinal edema Diabetic Retinopathy: Distinctions and Classifications Non-Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (NPDR) - according to Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) Numerous fundus finding exclusive of neovascularization Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy Anything also found in NPDR Neovascularization Diabetic Maculopathy Can occur in any stage in NPDR or PDR Hard exudates Dot & blot hemorrhages CSME CSME is the only treatable form of diabetic maculopathy Poor prognosis if: Hard exudates in fovea Poor initial acuity Longstanding duration Broken perifoveal capillary net Good prognosis if: Exudates are away from foveal avascular zone Good acuity Short duration Intact perifoveal net Treating Diabetic Macular Edema: Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS): FA to identify leakage area Argon laser CSME only treated Moderate vision loss = doubling of the visual angle (e.g., Going from 20/20-20/40) Focal photocoagulation of CSME reduces risk of moderate vision loss by 50% Treat all leaking microaneurysms more that 500 microns from the fovea Focal microaneurysm leakage on FA - focal photocoagulation Diffuse leakage on FA - grid photocoagulation Re-evaluate in 2-4 mos (need for additional treatment common) Treat CSME before PRP (if needed) as PRP can worsen CSME Cataract extraction can worsen CSME Newest treatments for Diabetic Macular Edema Intravitreal injection of steroids for macular edema. Stabilizes vascular membranes and reduces vascular permeability. Intravitreal injection of anti- antigenic (anti-VEGF) drugs such as Avastin (bevacizumab) and Lucentis (ranibizumab) Stabilizes vascular membranes and reduces vascular permeability by down regulating VEGF (which increases vascular permeability). EYLEA® (aflibercept) VEGF-trap Binds to VEGF WET (EXUDATIVE) AMD: CHOROIDAL NEOVASCULARIZATION 8-20% of cases of AMD are wet (actually, up to 12% may be unknown, according to Framingham study) Presence of exudate, hemorrhages, or suspected gray-green lesion as this implies that choroidal neovascularization and wet AMD has formed. However, hemorrhage or exudation may obscure part or all of CNVM Choroidal Neovascularization Bruch's disruption Diffuse thickening of Bruch’s with soft drusen which predisposes to breaks in Bruch’s membrane Presence of VEGF enhances development Other diseases can cause Bruch’s disruption RPE/ Bruch's breaks Diffuse thickening with soft drusen predisposes Bruch’s membrane to breaks Soft drusen often precursor, but not always Chronic Inflammation Theory Higher number of lymphocytes, macrophages, fibroblasts found in Bruch’s membranes of patients with AMD Inflammation causes breaks in Bruch’s membrane? Implication are not yet understood Choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM) infiltrates from choriocapillaris Under the RPE and sensory retina RPE detachment with turbid fluid or blood may represent CNVM Round/oval gray-green elevation Don’t look only for gray-green appearance. Look for fluid and blood. Associated findings: Lipid exudate Blood Sensory RD Classic CNVM Well defined membrane on angiogram About 10% of cases Occult CNVM About 90% of cases Ill defined membrane on angiogram CNVM may be subfoveal, juxtafoveal (1-199 microns from center of macula), or extrafoveal (> 200 microns from center of macula FA and possibly indocyanine green (ICG) imaging: hot spots with late spread of hyperfluorescence. Must get FA within 72 hrs because membranes can grow 10 microns/day; Suspected/actual CNVM is an ocular urgency ICG may be indicated to better visualize outline of membrane ICG dye absorbs and emits fluorescence in the near IR spectrum Better able to penetrate hemorrhage, melanin, fluid Better for occult CNVM detection Hypoxia and VEGF RPE tear Serous RPE detachments Hemorrhagic RPE/sensory retinal detachments 10% risk of wet AMD in 4.3 yrs if pt. has bilateral macular drusen 90% of pts. who are legally blind from AMD have wet AMD VA 20/200-20/800 Wet (Exudative) AMD: Disciform Scarring: Fibrovascular material following CNVM development Most cases of CNVM progress to this stage Replaces most of sensory retina, RPE May continue to grow and invade new areas Results in death of tissue and severe visual loss Yellow-brown-black (RPE hyperplasia) Surgical excision may modestly improve vision Wet AMD: Management Laser photocoagulation Photodynamic therapy (PDT) Intravitreal steroid injection Anti-angiogenic factors Avastin, Lucentis, Eyelea UV protection Anti-oxidant vitamin therapy Macular drusen - home amsler Low vision consult Wet AMD: Anti-angiogenic Therapy Macugen (pegaptanib sodium) Oligonucleotide with high affinity for VEGF, preventing its uptake by endothelial receptors Intravitreal injection q 6 weeks Historical at this point. FDA approved and available but not used Lucentis (ranibizumab) Recombinant anti-VEGF antibody fragment that binds to VEGF Intravitreal injection q 4 weeks FDA approved and more successful than Macugen 94% of eyes with stable or improved vision at 98 days On average, two lines of vision gained 26% of eyes improved three or more lines at 98 days EYLEA (aflibercept) Recombinant fusion protein consisting of portions of human VEGF receptors 1 and 2. It is considered a VEGF-trap in that it causes VEGF to bind with it rather than retinal VEGF receptors and reduces retinal effects of VEGF May have higher affinity for VEGF-A, thus potentially more therapeutic effect and fewer injections Avastin (bevacizumab) Anti-colon cancer drug; accidentally found when patients with wet AMD patients undergoing chemotherapy reported improved vision Not FDA approved for this use (monthly intravitreal injection for AMD), but very popular and economical CENTRAL SEROUS CHORIORETINOPATHY (CSC) Sometimes known as idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy (ICSC) Serous retinal or pigment epithelial detachments in macular area Loss of foveal reflex Transient and potentially recurrent Recurrence rate is 20-30% Breakdown of RPE cells allowing seepage to occur into sensory retina Typically, a focal conduit through RPE into sensory retina Theorized to occur secondary to vasomotor instability or sympathetic nervous excitation Predisposing conditions such as drusen are absent RPE detachment can commonly occur simultaneously RPE separates from Bruch's; retina separates from RPE Due to RPE disruption, there may be associated RPE hyperplasia Male: female 10:1 20-50 yrs (mid 30's). This should not be diagnosed in a patient over age 55 yrs Must look for CNVM in older pts. Type A personality Caucasian FA appearance: smokestack with 1 or 2 well demarcated cavities. Sensory RD is diffuse RPE detachment is well demarcated Presents with decreased VA, metamorphopsia, hyperopic shift Highly associated with steroid use (of all kinds) PDT has shown some decent effect; anti-VEGF treatment has had only limited success Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: Management Home amsler and observation Discontinue all steroids Excellent prognosis 60% recover 20/20 1-6 mos course Self-limiting RPE decompensation may complicate matters. "sick RPE syndrome" Focal dysfunction of RPE resulting in slow, chronic oozing through RPE Retina and RPE remain flat Poor prognosis Decreased VA with RPE changes Possible CNVM formation Direct photocoagulation to leaking areas in severe or non-remitting cases Treatment does not affect rate of recurrence or final acuity; it only hastens the process Laser may aggravate pre-existing choroidal neovascular membrane or ICSC. This is ‘like putting fertilizer on a weed’.